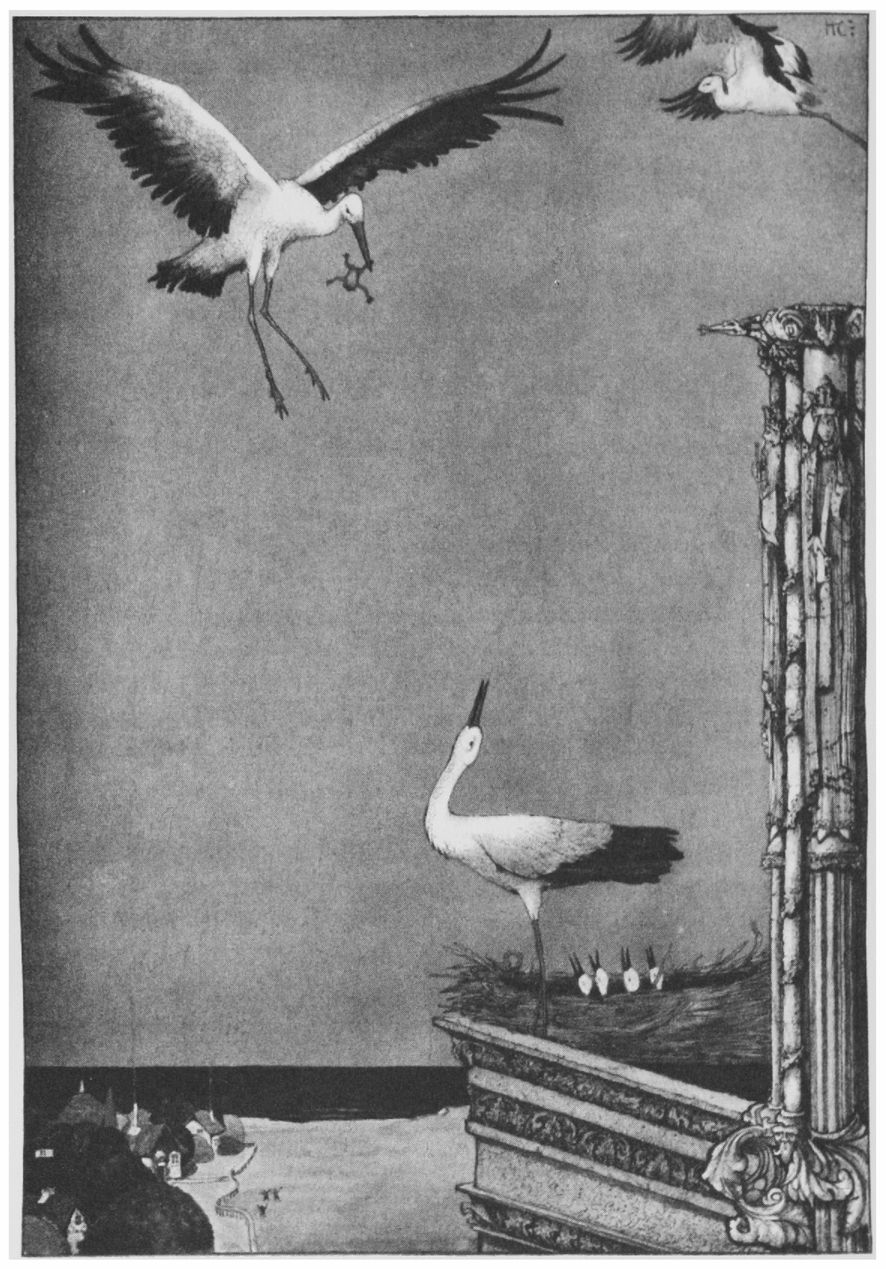

THE STORKS

ON THE LAST HOUSE in a little town there was a

stork’s nest. The stork mother sat in the nest with her four little

children, who stuck their heads out with their little black beaks

that hadn’t turned red yet. A little distance away on the top of

the roof, stork father was standing straight and stiff. He had

pulled one leg up under him in order to take a few pains while he

was standing sentry. You would think he was carved from wood,

that’s how still he stood. “It must look pretty impressive that my

wife has a sentry by the nest,” he thought. “They can’t know I’m

her husband. They probably think I’ve been commanded to stand here.

It looks very impressive!” and he continued to stand on one

leg.

Down on the street a whole gang of children were

playing, and when they saw the storks, first the boldest boy and

then the others sang the old ditty about the storks, but they sang

it the way they remembered it:

“Fly Storky storky!

Fly home to your door!

Your wife’s sitting there

With baby storks four.

One will be hanged,

And the second be penned.

The third will be burned,

And the fourth turned on end!”

Fly home to your door!

Your wife’s sitting there

With baby storks four.

One will be hanged,

And the second be penned.

The third will be burned,

And the fourth turned on end!”

“Listen to what the boys are singing,” the little

storks said. “They say we’ll be hanged and burned!”

“Don’t pay any attention to that,” said the stork

mother. “Just don’t listen, and it won’t matter.”

But the boys kept singing, and they pointed at the

storks. Only one boy, whose name was Peter, said that it wasn’t

nice to make fun of the animals and wouldn’t have anything to do

with it. The stork mother consoled her children. “Don’t worry about

it,” she said, “Just see how calmly your father is standing there

and on one leg too!”

“We’re so scared,” said the little storks, and drew

their heads way down into the nest.

The next day when the children gathered again to

play, they saw the storks and started their song:

“The first will be hanged,

The second be burned!”

The second be burned!”

“Are we going to be hanged and burned?” asked the

stork babies.

“No, certainly not,” their mother answered. “You’re

going to learn to fly. I’ll train you. Then we’ll fly out to the

meadow and visit the frogs. They’ll bow down to us in the water,

and say ”croak, croak,” and then we’ll eat them up. It’ll be lots

of fun.”

“And then what?” asked the little storks.

“Then all the storks in the country gather

together, and we have fall maneuvers. You have to be able to fly

well by then. It’s very important because those who can’t fly are

stabbed to death by the General’s beak. So be very sure to learn

your lessons when the training starts!”

The storks.

“So we’ll be killed then anyway like the boys said,

and listen: they’re singing it again.”

“Listen to me and not to them,” stork mother said.

“After the big maneuvers we’ll fly to the warm countries. Oh far,

far from here, over mountains and forests. We’ll fly to Egypt where

they have three-sided stone houses that end in a point up over the

clouds. They are called pyramids and they are older than any stork

can imagine. There’s a river there that overflows so that the land

becomes muddy. You walk in the mud and eat frogs.”

“Oh!” all the children said.

“Yes, it’s so lovely. You don’t do anything but eat

the whole day, and while we have it so good there, there’s not a

green leaf to be seen on the trees here. It’s so cold here that the

clouds freeze to pieces and fall down in little white patches.” It

was snow she meant, but she couldn’t explain it any better.

“Do the naughty boys also freeze to pieces?” asked

the stork babies.

“No, they don’t freeze to pieces, but they aren’t

far from it, and they have to sit inside their dark houses and

twiddle their thumbs. But you, on the other hand, will fly around

in foreign lands where there are flowers and warm sunshine.”

Time passed, and the young storks were so big that

they could stand up in the nest and look all around, and stork

father flew in every day with frogs, little grass snakes, and other

tasty storky snacks that he found! Oh, it was fun to see the tricks

he did for them! He lay his head way back on his tail, and he

clattered his beak as if it were a little rattle, and then he told

them stories from the marsh.

“All right, now you must learn to fly,” said stork

mother one day, and all four young storks had to go out on the

ridge of the roof. Oh, how they tottered! They balanced with their

wings but almost fell over!

“Watch me,” mother said. “Hold your heads like

this. Place your legs like this. One, two! One, two! This is

what’ll get you moving up in life.” Then she flew a little

distance, and the children made a little clumsy hop and thud! There

they lay because their bodies were too heavy.

“I don’t want to fly,” said one young stork, and

climbed back into the nest. “I don’t care about getting to the warm

countries.”

“Do you want to freeze to death here when winter

comes? Shall the boys come and hang and burn and beat you? I’ll

call them.”

“Oh no,” said the young stork, and hopped out on

the roof again with the others. By the third day they could

actually fly a little, and they thought that they could sit and

rest on the air too. They tried that, but thud! They took a tumble,

and so they had to move their wings again. There came the boys down

on the street, singing their song,

“Fly storky storky ... ”

“Shouldn’t we fly down and peck their eyes out?”

asked the young storks.

“No, forget about it,” said their mother. “Just

listen to me. That’s much more important. One, two, three, fly to

the right. One, two, three, now left around the chimney.—Oh, that

was very good! That last stroke of the wings was so lovely and

correct that you’ll all be allowed to come to the swamp with me

tomorrow. Several fine stork families will be coming there with

their children. Let me see that mine are the prettiest, and be sure

to hold your heads high. That looks good, and others will respect

you.”

“But won’t we get revenge on the naughty boys?”

asked the young storks.

“Let them cry whatever they want. You’ll fly above

the clouds, and come to the land of the pyramids, while they must

freeze here without a green leaf or a sweet apple.”

“But we’ll get revenge,” they whispered to each

other, and then there were more maneuvers to do.

Of all the boys in the street none was worse at

singing the cruel ditty than the one who had begun it, and he was

quite a small boy, not more than six years old. The young storks

thought he was a hundred because he was quite a bit bigger than

their mother and father, and what did they know about how old or

big humans could be? They determined to be revenged on this one

boy—he had started it, and he kept it up. The young storks were so

irritated, and as they became bigger, they tolerated it even less.

Their mother finally had to promise them that they would get

revenge, but not until the last day they were to be in the

country.

“First we have to see how you manage the big

maneuvers. If you don’t do well so that the General stabs his beak

in your chests, then the boys would be right, at least in a way.

Let’s wait and see.”

“And see you shall!” said the young ones, and they

really took great pains. They practiced every day and flew so

lovely and lightly that it was a pleasure to see them.

Then fall came, and all the storks started

gathering to fly away to the warm countries while we have winter

here. What a maneuver! They flew over the forests and towns just to

see how well they could fly. There was a big trip lying ahead of

them. The young storks did their flying so beautifully that they

graduated frog and snake cum laude. That was the best possible

mark, and they could eat the frog and snake, which they also did at

once.

“Now our revenge!” they said.

“Yes indeed,” said the stork mother. “I have

thought of just the thing. I know where the pond is where all the

little humans lie until the stork comes and brings them to their

parents. The lovely little ones dream and sleep as beautifully as

they never will again. All parents would gladly have such a little

child, and all children want a brother or a sister. Now we’ll fly

to the pond and get a little child for each of those who didn’t

sing the naughty song and make fun of the storks, because those

naughty children shouldn’t get one!”

“But what about the one who started the song, the

naughty, nasty boy,” cried the young storks. “What’ll we do to

him?”

“In the pond there is a little dead child that has

dreamed itself to death. We’ll bring it to him, and then he must

cry because we have brought him a dead little brother. But you

haven’t forgotten the good little boy have you? The one who said,

‘It’s a shame to make fun of the animals?’ We’ll bring him both a

brother and a sister and since that boy was named Peter, you will

all be called Peter too.”

And it happened as she said, and all the storks

were named Peter, and that is what they’re called to this very

day.