THE HILL OF THE ELVES

SOME FIDGETY LIZARDS WERE running around in the

cracks of an old tree. They could understand each other very well

because they spoke lizard language.

“My, how it’s rumbling and humming in the old elf

hill!” said one lizard. “I haven’t been able to close my eyes for

two nights because of the noise. I could just as well be lying

there with a toothache because then I don’t sleep either!”

“There’s something going on in there,” said the

second lizard. “They had the hill standing on four red pillars up

until cockcrow. They’re really airing it out, and the elf maidens

have learned some new dances that have stamping in them. Something

is going on.”

“I’ve talked to an earthworm of my acquaintance,”

said the third lizard. “He was right up at the top of the hill,

where he digs around night and day. He heard quite a bit. Of course

he can’t see, the miserable creature, but he can feel around and

understands how to listen. They are expecting guests in the elf

hill, distinguished guests, but who they are he wouldn’t say, or he

probably didn’t know. All the will-o’-the-wisps have been reserved

to make a torchlight procession, as it’s called, and the silver and

gold—and there’s enough of that in the hill—is being polished and

set out in the moonlight.”

“But who in the world can the guests be?” all the

lizards asked. “I wonder what is going on? Listen to how it’s

humming! Listen to the rumbling!”

Just then the hill of the elves opened up, and an

old elf lady came toddling out. She had a hollow back, but was

otherwise very decently dressed. She was the old elf king’s

housekeeper and a distant relative. She had an amber heart on her

forehead. Her legs moved very quickly: trip, trip. Oh, how she

could get around, and she went straight down in the bog to the

nightjar!

“You’re invited to the elf hill tonight,” she said,

“but first will you do us a tremendous favor and see to the

invitations? You must make yourself useful since you don’t have a

house yourself. We’re having some highly distinguished guests—very

important trolls—and the old elf king himself will be there.”

“Who’s to be invited?” asked the nightjar.

“Well, everyone can come to the big ball, even

people, so long as they can talk in their sleep or do one or

another little bit in our line. But for the main banquet the guests

are very select. We are only inviting the absolutely most

distinguished. I have argued with the elf king about this because

I’m of the opinion that we can’t even let ghosts attend. The merman

and his daughters have to be invited first. They aren’t crazy about

coming onto dry land, but each of them will have a wet rock or

better to sit on, so I don’t think they’ll refuse this time. We

must have all the old trolls of the highest rank with tails, the

river sprite, and the pixies. And I don’t think we can exclude the

grave-hog, the hell-horse, or the church-shadow. Strictly speaking

they belong to the clergy, not our people, but it’s just their jobs

after all, and they are close relatives and visit us often.”

“Suuuper!” croaked the nightjar and flew away to

issue invitations.

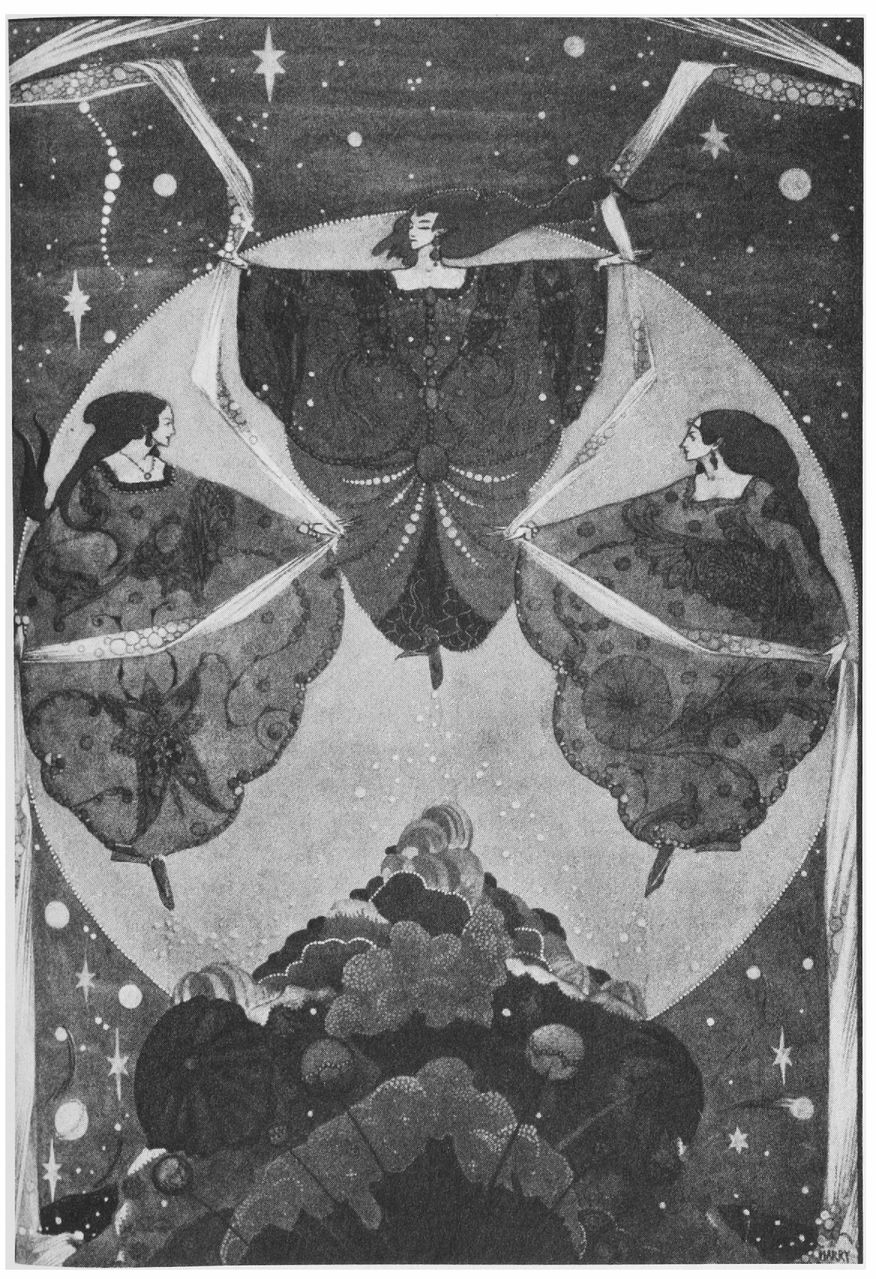

The elf maidens were already dancing on the elf

hill, and they danced in long shawls woven from mist and moonlight,

which is lovely for those who enjoy this type of thing. Way inside

the middle of the elf hill the big hall had been fixed up. The

floor had been washed with moonlight, and the walls were polished

with witches’ wax, so they shone like tulip petals in the light.

The kitchen was full of frogs on the spit, little children’s

fingers rolled in grass snake skins, and salads of mushroom seeds,

wet snouts of mouse, and hemlock. There was beer from the bog

woman’s brewery, and saltpeter wine from the tomb cellar. It was

hearty fare. Desert was rusted-nail hard candy, and church window

glass tidbits.

They danced in long shawls woven from mist

and moonlight.

The old elf king had his golden crown polished in

slate pencil powder. It was deluxe powder, from the smartest boy’s

pencil, and it’s very hard for the elf king to get hold of that.

They hung up curtains in the bedroom and fastened them up with

snake spit. Yes, there was quite a hustle and bustle!

“Now we’ll fumigate with curled horsehair and pig

bristles, and then I think my share of the work will be done,” said

the old elf maid.

“Dear daddy,” said the smallest daughter, “Won’t

you tell who the distinguished guests are?”

“Well,” he said, “I guess I must tell you. Two of

you daughters must prepare to get married—because two of you are

going to get married. The troll king from Norway—the one who lives

in the Dovre mountain and has many granite mountain castles and a

gold mine that’s worth more than people think1—is

coming with his two boys. Each of them is looking for a wife. The

troll king is one of those down-to-earth, honest old Norwegian

fellows, cheerful and straightforward. I know him from the old days

when we were on familiar terms with each other. He had come down

here for a wife. She is dead now. She was the daughter of the chalk

cliff king from Moen.2 You

could say she was chalked up to be his wife. Oh, how I’m looking

forward to seeing him! They say that his boys are a couple of

bratty conceited fellows, but that may not be true, and the acorn

doesn’t fall far from the tree. They’ll straighten out when they

get older. You girls will whip them into shape!”

“When are they coming?” one daughter asked.

“It depends on the wind and weather,” the elf king

said. “They are traveling by the cheapest method and will come when

they can obtain passage on a ship. I wanted them to come by way of

Sweden, but the old fellow wouldn’t think of it! He doesn’t keep up

with the times, and I don’t like that!”3

Just then two will-o’-the-wisps came hopping, one

faster than the other, and so one came first.

“They’re coming! They’re coming!” they

shouted.

“Give me my crown, and I’ll go stand in the

moonlight!” said the elf king.

His daughters lifted their long shawls and curtsied

right down to the ground.

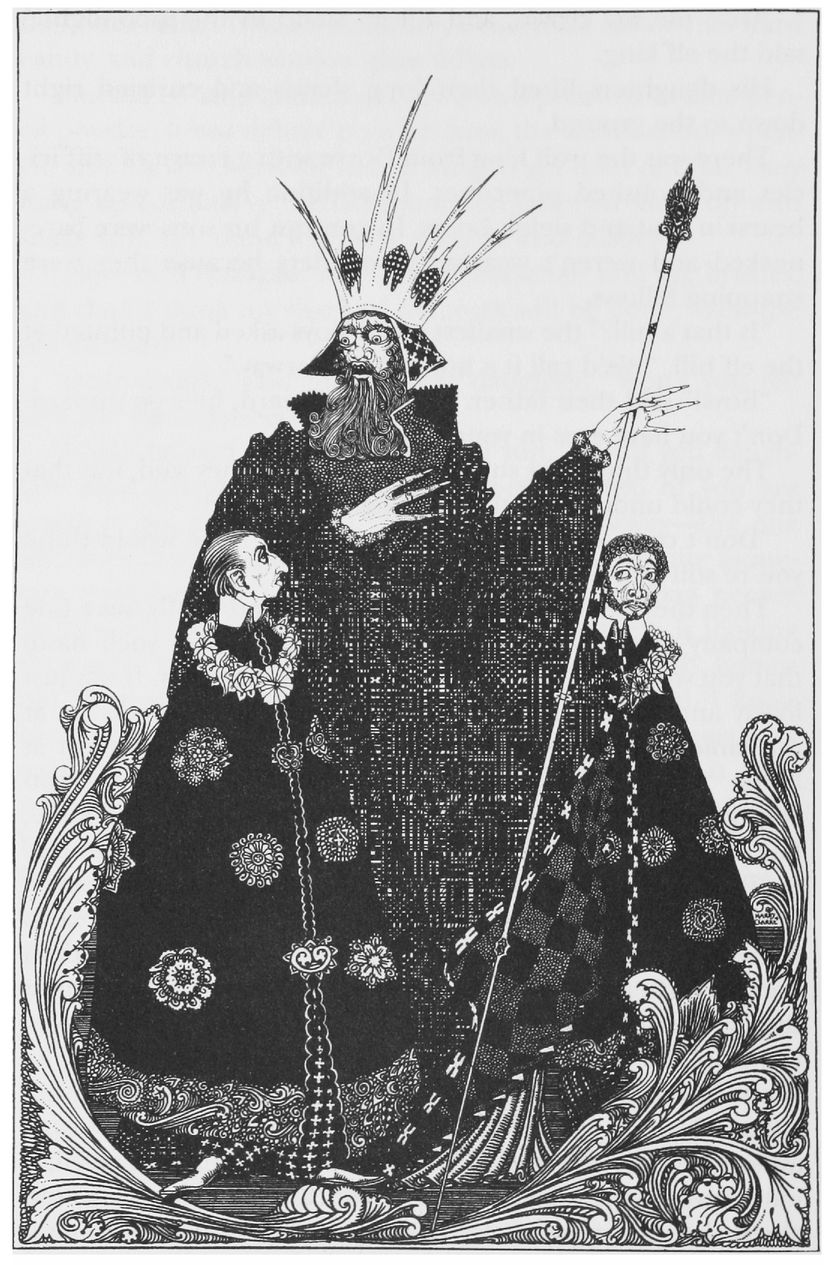

There was the troll king from Dovre with a crown of

stiff icicles and polished pinecones. In addition he was wearing a

bearskin coat and sleigh boots. In contrast his sons were

bare-necked and weren’t wearing suspenders because they were

strapping fellows.

“Is that a hill?” the smallest of the boys asked

and pointed at the elf hill. “We’d call it a hole up in

Norway.”

“Boys!” said their father. “Holes go inward, hills

go upward. Don’t you have eyes in your heads?”

The only thing that surprised them here, they said,

was that they could understand the language right away!

“Don’t carry on now!” said the old king, “one would

think you’re still wet behind the ears.”

Then they went into the elf hill, where there

really was a fine company assembled. They had been gathered in such

haste that you would think they had been blown together. It was

just lovely and neatly arranged for everyone. The sea folks sat at

the table in big vats of water and said that they felt right at

home. All of them had good table manners except the two young

Norwegian trolls. They put their feet up on the table, but then

they thought that everything they did was becoming.

“Feet out of the food!” said the old troll, and

they obeyed him but not right away. They tickled the elf maidens

next to them with pinecones that they had in their pockets, and

then they took their boots off to be comfortable and gave them to

the elf maidens to hold. But their father, the old Dovre troll, was

completely different. He told lovely stories about the glorious

Norwegian mountains, and about the waterfalls that rushed down in

white foam with a roar like thunder and organ music. He told about

the salmon that jumped up the rushing waters when the water sprite

played its gold harp. He told about the glistening winter nights

when the sleigh bells rang out, and the lads ran with burning

torches over the shiny ice that was so transparent that they could

see the fish swim away in fright underneath their feet. He could

tell stories so that you could see and hear what he talked about:

it was as if the sawmills were going, as if the boys and girls sang

folksongs and danced the hailing. Suddenly the old troll gave the

old elf maiden a hearty familial smack—it was a real kiss—and they

weren’t even related!

“Don’t carry on now!” said the old

king.

Then the elf maidens had to dance, and they danced

both slowly and the tramping dance, and it suited them very well.

Then they did the hardest dance, the one that’s called “stepping

out of the dance.” Oh my! How they kicked up their legs. You

couldn’t tell what was the beginning or what was the end. You

couldn’t tell arms from legs. They swirled around each other like

sawdust, and then they twirled around so that the hell-horse got

sick and had to leave the table.

“Prrrr ... they can surely shake a leg,” said the

troll king, “but what else can they do besides dance, do high

kicks, and make whirlwinds?”

“You’ll see,” said the elf king, and he called his

youngest daughter forward. She was very slender and as clear as

moonlight. She was the most delicate of all the sisters. She put a

white twig in her mouth, and then she disappeared. That was her

skill.

But the old troll said that he wouldn’t tolerate

such a skill in his wife, and he didn’t think his boys would like

it either.

The second one could walk beside herself as if she

had a shadow, and trolls don’t have those.

The third was quite different from the others. She

had been in training at the bog woman’s brewery, and she knew how

to garnish elder stumps with glowworms too.

“She’ll be a good housewife!” said the old troll,

and he drank to her with his eyes because he didn’t want to drink

too much.

Then the fourth elf maiden came to play a big

golden harp. When she played the first string, they all lifted

their left legs because trolls are left-legged, and when she played

the second string, they all had to do what she wanted.

“That’s a dangerous woman,” said the old troll, but

both of his sons left the hill because they were bored.

“What can the next daughter do?” asked the troll

king.

“I have become so fond of Norwegians,” she said,

“and I’ll never marry unless I can come to Norway.”

But the smallest daughter whispered to the old

troll, “It’s just because in a Norwegian song she heard that when

the world comes to an end, the Norwegian mountains will stand like

a monument, and she wants to get up there because she’s afraid of

dying.”4

“Ho, ho,” laughed the troll king. “So that’s the

scoop. But what can the seventh and last daughter do?”

“The sixth comes before the seventh,” said the elf

king because he could count, but the sixth didn’t want to come

out.

“All I can do is tell people the truth,” she said.

“Nobody cares about me, and I have enough to do sewing my burial

shroud.”

Now came the seventh and last, and what could she

do? Well, she could tell fairy tales, and as many as she wanted

to.

“Here are my five fingers,” said the old troll.

“Tell me one about each of them.”

And the elf maiden took him by the wrist, and he

laughed so hard he gurgled, and when she came to the ring finger

that had a golden ring around its middle as if it knew there was

going to be an engagement, the troll king said, “Hold on to what

you have! My hand is yours! I want to marry you myself.”

And the elf maiden said there were still stories to

hear about the ring finger and a short one about little Per

Pinkie.

“We’ll hear those in the winter,” said the old

troll, “and we’ll hear about the spruce trees and the birch and

about the gifts of the hulder people and the tinkling frost. You

will be telling stories for sure because nobody up there can do

that very well yet. And we’ll sit in the stone hall by the light of

the blazing pine chips and drink mead from the golden horns of the

old Norwegian kings. The water sprite has given me a couple of

them. And as we’re sitting there, the farm pixie will come by for a

visit. He’ll sing you all the songs of the mountain dairy girls.

That’ll be fun. The salmon will leap in the waterfalls and hit the

stone wall, but they won’t get in! Oh, you can be sure it’s

wonderful in dear old Norway. But where are the boys?”

Well, where were the boys indeed? They were running

around in the fields blowing out the will-o’-the-wisps, who had

come so good-naturedly to make the torchlight parade.

“What’s all this gadding about?” said the troll

king. “I’ve taken a mother for you, now you can take wives among

your aunts.”

But the boys said that they would rather give a

speech and drink toasts. They had no desire to get married. And

then they gave speeches, drank toasts, and turned the glasses over

to show that there wasn’t a drop left. Then they took off their

coats and lay down on the table to sleep because they weren’t a bit

self-conscious. But the troll king danced all around the hall with

his young bride, and he exchanged boots with her because that’s

more fashionable than exchanging rings.

“The rooster’s crowing!” said the old elf who was

the housekeeper. “Now we have to shut the shutters so the sun

doesn’t burn us to death.”

And the elf hill closed.

But outside the lizards ran up and down the cracked

tree, and one said to the other:

“Oh, I really liked that old Norwegian troll

king!”

“I liked the boys better,” said the earthworm, but

of course he couldn’t see, the miserable creature.

NOTES

1

Andersen likely took this motif from Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and

Jørgen Moe’s famous Norwegian folktale collection Norske

folkeeventyr, the first volume of which appeared in 1841.

Dovrefjell is a mountain range south of Trondheim.

2

According to folklore, a supernatural creature was thought to live

inside the chalk cliffs on Moen, an island in the Baltic Sea off

the Danish coast.

3

Reference to Norwegian opposition to the 1814 union with

Sweden.

4

Reference to the first line of the poem “Til mit födeland” (“To My

Native Land”), by S. O. Wolff (1796-1859), which appeared in

Samlede poetiske forsög lst. volume, published in

Christiania in 1833. The first line is “Hvor herligt er mit

Fødeland” (“How splendid is my native land”).