THE TINDERBOX

A SOLDIER CAME MARCHING along the road: One, two!

One, two! He had his knapsack on his back and a sword by his side,

for he had been to war, and now he was on his way home. As he was

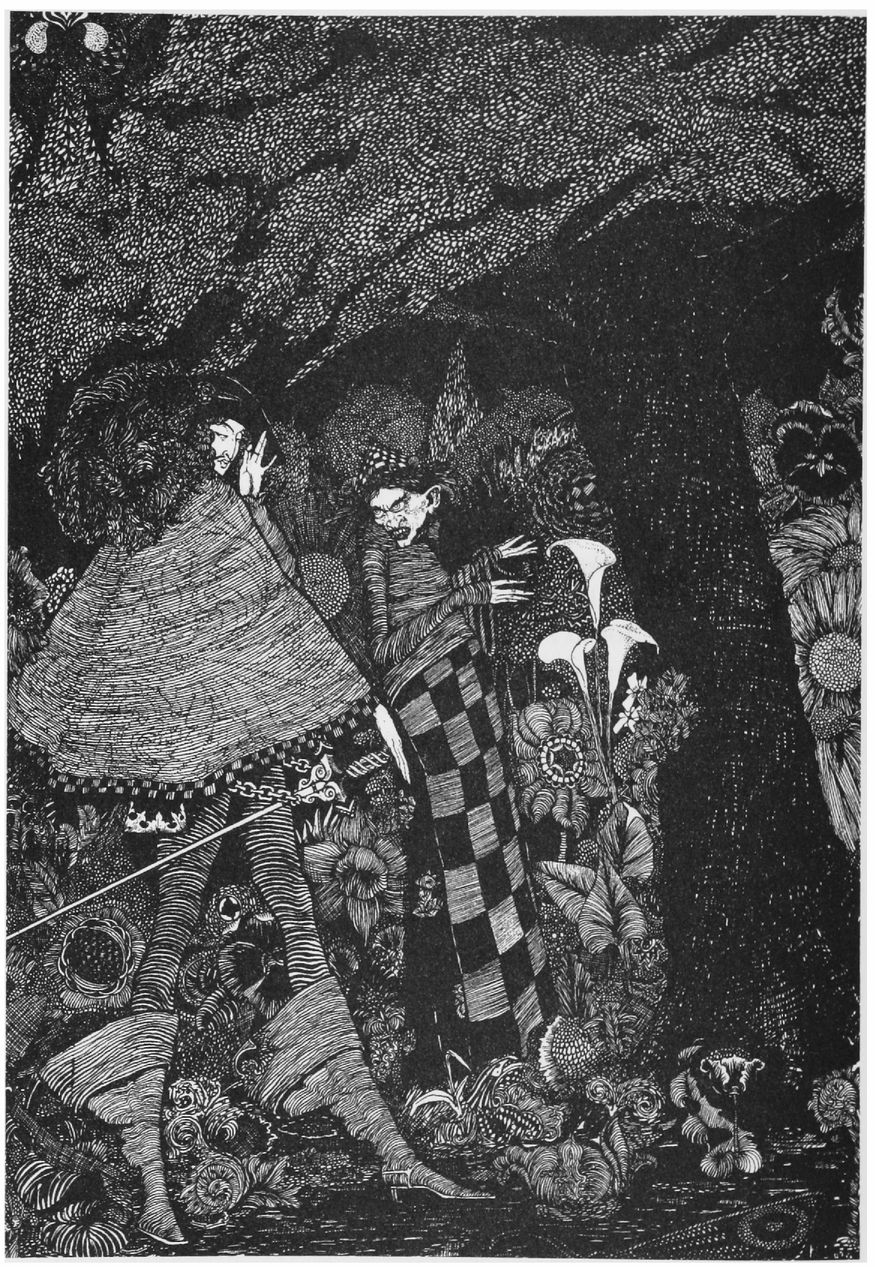

striding along the road, he met an old hag. She was so disgusting

that her lower lip hung down on her chest. “Good evening, soldier,”

she said. “What a handsome sword and big knapsack you have! You’re

a real soldier! And now you’re going to get as much money as you

could ever want.”

“Thanks very much, old hag,” the soldier

replied.

“Do you see that big tree?” asked the hag, and

pointed at a tree beside them. “It’s completely hollow inside.

Climb up to the top, and you’ll see a hole that you can slide

through. I want you to go deep down inside the tree, and I’ll tie a

rope around your waist so that I can pull you up when you call

me.”

“And what should I do down in the tree?” asked the

soldier.

“Get money!” said the hag, “Listen, when you reach

the bottom of the tree, you’ll be in a big passage. It will be

quite bright there because there are over a hundred burning lamps.

You’ll see three doors, and you can open them because the keys are

in the locks. When you go into the first room, you’ll see a large

chest in the middle of the floor with a dog sitting on top of it.

He has eyes as big as a pair of teacups, but don’t worry about

that. I’ll give you my blue-checkered apron that you can spread out

on the floor, but move quickly, take the dog, and set him on the

apron. Then open the chest and take as many coins as you want.

They’re all made of copper, but if you would rather have silver, go

into the next room where you’ll see a dog with eyes as big as a

mill wheel, but don’t worry about that. Set him on my apron and

take the money! On the other hand, if you want gold, you can have

that too, and as much as you can carry, if you go into the third

room. But the dog that is sitting on the money chest in there has

two eyes, each as big as the Round Tower,1 and that’s

quite a dog, I can tell you, but don’t worry about it! Just set him

on my apron, and he won’t do anything to you, so you can take as

much gold as you want from the chest.”

“And what should I do down in the tree?”

asked the soldier.

“That doesn’t sound too bad,” said the soldier,

“but what am I to give you, you old hag? For you want something, I

imagine.”

“No,” said the hag, “I don’t want a single penny.

Just bring me an old tinderbox that my grandmother forgot the last

time she was down there.”

“Very well! Let’s wrap that rope around my waist,”

said the soldier.

“Here it is,” said the hag, “and here’s my

blue-checkered apron.”

Then the soldier climbed into the tree, slid down

the hole, and found himself, as the hag had said, in the big

passageway, where hundreds of lamps were burning.

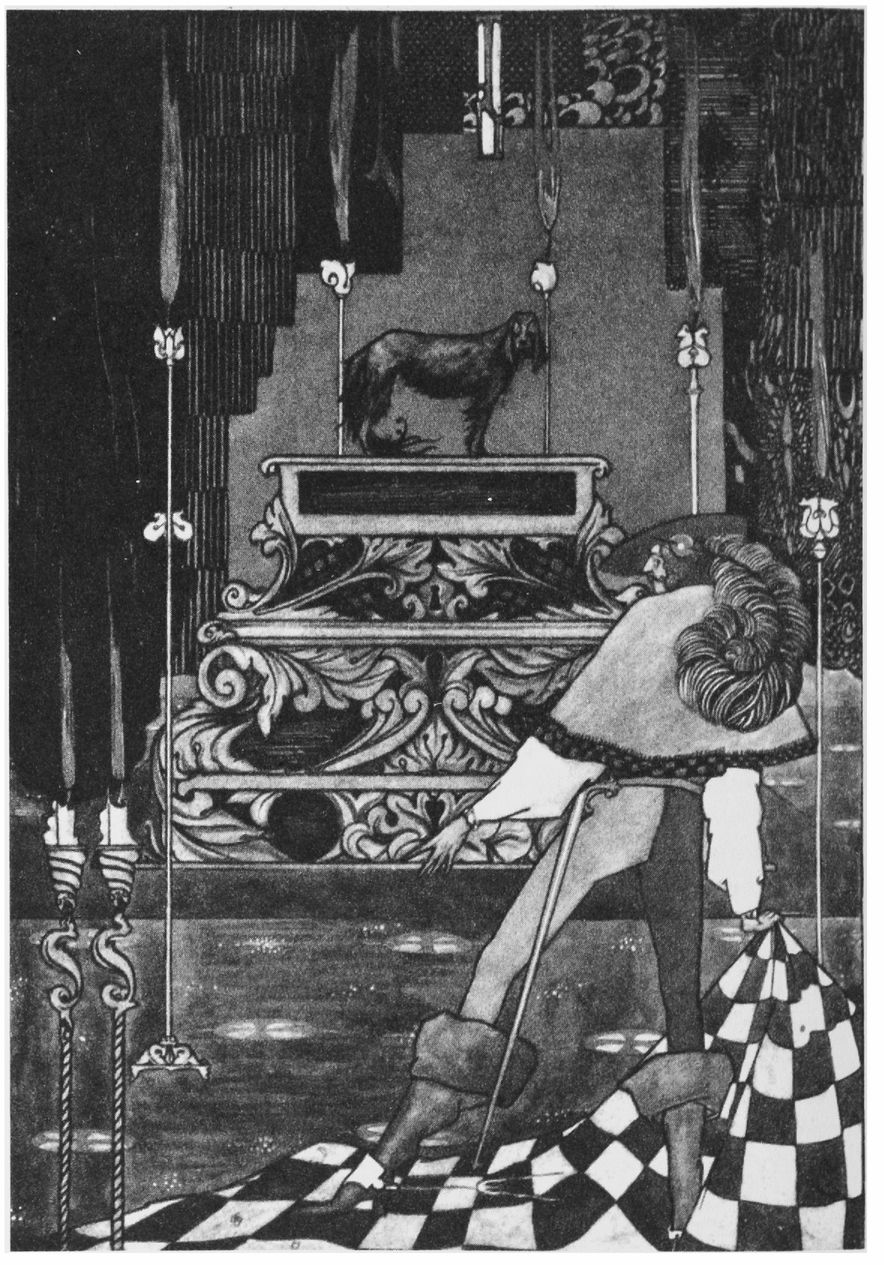

He opened the first door. Oh! There sat the dog

with eyes as big as teacups, glaring at him.

“You’re a fine fellow!” said the soldier, and he

set him on the hag’s apron and took as many copper coins as he

could pack into his pockets. Then he closed the chest, put the dog

back, and went into the second room. Yikes! There sat the dog with

eyes as big as mill wheels.

“Stop staring at me so much!” said the soldier.

“You might hurt your eyes!” and he set the dog on the hag’s apron.

When he saw so many silver coins in the chest, he threw away the

copper money and filled his pockets and his knapsack with the

silver coins. Then he went into the third room!—Oh, the dog was so

repulsive! It really did have two eyes as big as the Round Tower

that rolled around in its head like wheels!

“Good evening,” said the soldier and tipped his

cap, for he had never seen such a dog before. But after he had

looked at him a little, he thought, enough of that! He lifted him

down to the floor and opened up the chest. Oh, bless me! How much

gold there was! He could buy all of Copenhagen and all the

pastry-women’s candied pigs, all the tin soldiers, riding crops and

rocking horses there were in the world! Now there was

money!—Then the soldier threw away all the silver coins he had

poured into his pockets and knapsack and took gold instead. All his

pockets, the knapsack, his cap and boots were so full that he could

barely walk! Now he had money! He put the dog on the chest, locked

the door and called up through the tree, “Hoist me up now, old

hag!”

There sat the dog with eyes as big as

teacups, glaring at him.

“Do you have the tinderbox with you?” asked the

hag.

“Oh, that’s right,” said the soldier, “I’d

completely forgotten it,” and he went and got it. The hag hoisted

him up, and there he was once again standing on the road with his

pockets, boots, knapsack and cap full of money.

“What do you want that tinderbox for?” asked the

soldier.

“That doesn’t concern you,” said the hag, “Now that

you’ve got your money, just give me the tinderbox!”

“Nothing doing!” said the soldier. “Tell me right

now what you want it for, or I’ll pull out my sword and chop off

your head!”

“No,” said the hag.

So the soldier chopped her head off, and there she

lay. But he wrapped all his money up in her apron, stuck it into

his knapsack on his back, put the tinderbox in his pocket, and

walked into town.

It was a lovely town, and he went to the very best

inn, asked for the very best rooms, and ordered his most favorite

foods because now he was rich.

The servant who polished his boots thought that

they were rather funny old boots for such a rich man to have, but

the soldier hadn’t bought new ones yet. The next day he did indeed

buy boots and beautiful clothes! Now the soldier was a

distinguished gentleman, and the people told him all about the fine

things to be found in their town, and about their king, and what a

lovely princess his daughter was.

“Where can I see her?” asked the soldier.

“You can’t see her at all,” they all answered. “She

lives in a big copper castle, surrounded by walls and towers. No

one but the king is allowed to go in and out of there, because he

was told by a fortuneteller that the princess is going to marry a

common soldier, and the king can’t bear the thought that this might

happen.”

“I would like to see her though!” thought the

soldier, but of course he wouldn’t be allowed to do that.

Now he lived merrily, went to the theater, took

drives in the king’s garden, and gave away lots of money to the

poor, which was kind of him. He knew from the old days how bad it

was not to have a cent to one’s name.—Now he was rich, had fine

clothes, and made many friends. Every one said that he was a nice

fellow, a proper cavalier, and the soldier liked this very much.

But since he gave away money every day, and did not have any coming

in, he finally had only two coins left and had to move away from

the handsome rooms where he had lived, into a tiny little chamber,

right beneath the roof, and had to brush his boots himself and sew

them up with a darning needle, and none of his friends came to see

him because there were too many steps to climb.

One evening it became very dark, and he couldn’t

even buy himself a candle. But then he remembered there was a

little stump of one in the tinderbox that the hag had asked him to

take from the hollow tree. So he took out the tinderbox and the

candle stump, and just as he struck the flint, causing sparks to

fly from the stone, the door sprang open, and the dog that had eyes

as big as teacups and whom he had seen beneath the tree, stood in

front of him and said, “What does my master command?”

“What’s this!” cried the soldier. “This is

certainly an interesting tinderbox if it will give me what I want

like this! Get me some money,” he said to the dog, and presto it

was gone! Then presto it returned and held a big bag full of coins

in its mouth.

Now the soldier understood what a wonderful

tinderbox it was. If he struck once, the dog who sat on the chest

with copper coins came. If he struck twice, the dog who had silver

money appeared, and if he struck three times, the one with the gold

coins came.-The soldier moved back into his handsome rooms and wore

beautiful clothes once again. Suddenly all his friends recognized

him, and once more they were so terribly fond of him.

Then one day he thought: it’s really odd that no

one gets to see the princess. She’s supposed to be so beautiful,

they all say, but what good is that when she always sits inside the

big copper castle with all the towers?—Can’t I get to see her

somehow? —Where’s my tinderbox! And then he struck the flint, and

presto the dog with eyes as big as teacups came.

“Even though it’s the middle of the night,” the

soldier remarked, “I very much want to see the princess, just for a

little moment!”

The dog was out the door at once, and before the

soldier could think about it, the dog was back again with the

princess. She sat sleeping on the dog’s back and was so lovely that

it was clear for all to see that she was a real princess. The

soldier couldn’t help himself. He had to kiss her, for he was a

true soldier.

Then the dog ran back with the princess, but when

morning came, and the king and queen were having tea, the princess

said that she was disturbed by a strange dream that she had in the

night about a dog and a soldier. She had ridden on the dog, and the

soldier had kissed her.

“That’s quite some story!” said the queen.

So one of the old ladies-in-waiting was ordered to

keep watch over the princess the next night to see if it was a real

dream, or what it could be.

The soldier longed so frightfully to see the lovely

princess again and had the dog go to her in the night. The dog took

her and ran as fast as he could, but the old lady-in-waiting put on

high boots and ran just as fast after them. When she saw that they

disappeared into a big house, she thought, “Now I know where it

is,” and she marked a large cross on the door with a piece of

chalk. Then she hurried home and went to bed, and the dog also came

back with the princess. When he saw the cross on the door where the

soldier lived, however, he took a piece of chalk and marked crosses

on all the doors in the whole town, and that was smart of him

because now the lady-in-waiting could not find the right door.

Indeed, there were crosses on all of them.

Early in the morning the king and queen, the old

lady-in-waiting, and all the officers came to see where the

princess had been.

“There it is!” said the king, when he saw the first

door with a cross on it.

“No, there it is, my dear,” said the queen, who saw

another door with a cross on it.

“But there’s one, and there’s one!” they all cried

out. Wherever they looked, there were crosses on the doors. So then

they realized that there was no use in searching further.

However, the queen was a very wise woman, who could

do more than just ride in a coach. She took her big golden

scissors, cut a large piece of silk into pieces, and sewed a lovely

little bag. She filled it with fine little grains of buckwheat,

tied it to the back of the princess, and when that was done, she

cut a little hole in the bag, so the grains could sprinkle out

wherever the princess would go.

During the night the dog came again, took the

princess on his back, and ran with her to the soldier, who was so

very fond of her, and dearly wished he were a prince so that he

might marry her.

When the dog ran back to the castle with the

princess, he failed to notice that the grain had spilled out all

the way from the castle to the soldier’s window. In the morning the

king and queen could easily see where their daughter had been, and

they ordered the soldier to be arrested and put into prison.

There he sat. Oh, how dark and boring it was! And

then they told him: “Tomorrow you’ll be hanged.” That wasn’t

pleasant to hear. Moreover, he had forgotten his tinderbox which he

had left at the inn. In the morning, through the bars of the little

window, he could see people hurrying from all parts of the town to

see him hanged. He heard the drums and saw the soldiers marching.

All the people were running along, and among them was also a

shoemaker’s boy wearing a leather apron and slippers. He was

running so fast that one of his slippers flew off and landed right

by the wall where the soldier was peering through the iron

bars.

“Hey, boy! Don’t be in such a hurry,” the soldier

told him. “Nothing will happen until I get there! So, if you’ll run

to where I live and bring me my tinderbox, I’ll give you four

silver coins. But don’t let the grass grow under your feet.”

The shoemaker’s boy was eager to get the four

silver coins and rushed off to fetch the tinderbox. He gave it to

the soldier, and—Well, listen to what happened!

Outside the town a big gallows had been built, and

all around stood the soldiers and thousands of people. The king and

queen sat on a beautiful throne right opposite the judge and the

entire council.

The soldier was already standing up on the ladder,

but when they wanted to place the noose around his neck, he said

that a condemned man was always granted a last wish before his

punishment. He wanted so very much to smoke his pipe—it would be

the last smoke he would get in this world.

The king didn’t want to deny him this wish, and so

the soldier took his tinderbox and struck the flint, one, two,

three! And there stood all three dogs: the one with eyes like

teacups, the one with eyes like mill wheels, and the one who had

eyes as big as the Round Tower!

“Help me!” the soldier cried out. “Don’t let them

hang me!”

Immediately the dogs tore into the judges and all

the councilors. They grabbed some by their legs and some by their

noses and threw them high up into the air so that they fell down

and were dashed to pieces.

“Not me!” screamed the king, but the largest dog

took both him and the queen and threw them after all the others.

Now the soldiers became frightened, and all the people shouted,

“Little soldier, you will be our king and marry the beautiful

princess!”

Then they placed the soldier in the king’s coach,

and all three dogs danced in front and roared “hurrah!” and boys

whistled through their fingers, and the soldiers presented arms.

The princess came out of the copper castle and became the queen and

was very pleased with that! The wedding lasted for eight days, and

the dogs sat at the table in wide-eyed wonder.

NOTE

1. Astronomical observatory, 118 feet tall, in the

heart of Copenhagen. King Christian IV laid the first stone in

1637; the observatory was completed in 1642.