THE GARDEN OF EDEN

ONCE THERE WAS A prince, and no one had so many or

such beautiful books as he had. He could read about and see

splendid pictures of everything that had happened in the world. He

could find out about all nationalities and every country, but there

was not a word about where the Garden of Eden was, and that was

what he thought most about.

When he was still quite little, just beginning his

education, his grandmother had told him that every flower in the

Garden of Eden was the sweetest cake, and each stamen the finest

wine. History was on one flower, geography or math tables on

another. All you had to do was eat the cakes to know your lessons.

The more you ate, the more history, geography, and math you would

take in.

He believed that as a boy, but as he grew older,

learned more, and became wiser, he understood, of course, that

there must be a far different kind of beauty in the Garden of

Eden.

“Oh, why did Eve pick from the tree of knowledge?

Why did Adam eat the forbidden fruit? It should have been me, and

then it wouldn’t have happened! Sin would never have come into the

world!”

He said it then, and he said it now that he was

seventeen years old. All he thought about was the Garden of

Eden.

One day he was walking in the forest. He walked by

himself because that was his favorite pastime.

Evening came. Clouds gathered, a rainstorm came up,

and rain fell as if the whole sky was a floodgate with water

gushing from it. It was as dark as it usually is at night in the

deepest well. Sometimes he slipped in the wet grass, and sometimes

he tripped over the bare rocks that stuck up from the rocky ground.

Water poured off everything, and there wasn’t a dry thread on the

poor prince. He had to climb up and over big boulders where the

water was seeping out of the thick moss. He was ready to drop, but

then he heard a strange whistling sound and saw in front of him a

big cave, all illuminated. Right in the middle was a fire so big

you could cook a stag on it, and that is exactly what was

happening. A magnificent stag with huge antlers was on a spit and

was slowly rotating between two felled spruce trees. There was an

elderly woman, tall and strong, like a man in disguise, sitting by

the fire, and throwing on one log after the other.

“Just come a little closer,” she said. “Sit down by

the fire so you can dry your clothes.”

“There’s a bad draft in here,” the prince said and

sat down on the floor.

“It’ll get even worse when my sons get home,” the

woman answered. “You’re in the Cave of the Winds now, and my sons

are the four winds. Do you understand that?”

“Where are your sons?” asked the prince.

“Well, it’s not so easy to answer a stupid

question,” the woman said. “My sons are out on their own. They’re

playing ball with the clouds up there in the sky,” and she pointed

up into the air.

“I see,” said the prince. “You talk a little

tougher and are not as mild as the women I’m used to.”

“Well, they must not have anything else to do then.

I have to be tough to keep my boys in check. But I can do it too,

even though they are pretty stiff-necked. Do you see those four

sacks hanging on the wall over there? They are just as afraid of

them as you were of the belt in the woodshed. I can fold the boys

up, let me tell you, and put them in the sacks without further ado.

They sit there and can’t get out to gad about until I say so. But

here’s one of them!”

It was the North Wind who breezed in with freezing

cold surrounding him. Big hail stones hopped around on the floor,

and snowflakes swirled all around. He was dressed in pants and a

jacket of bearskin, and a hood of sealskin covered his ears. He had

long icicles hanging from his beard, and one hailstone after

another rolled down the collar of his jacket.

“Don’t go right over to the fire,” the prince

shouted. “You can easily get frostbite on your face and

hands!”

“Frostbite!” The North Wind laughed out loud. “I

love frost! What kind of a whippersnapper are you, by the way? How

did you get to the Cave of the Winds?”

“He’s my guest,” said the old woman, “and if you’re

not satisfied with that explanation, you’ll go into the sack. You

know what to expect!”

That helped, and the North Wind told where he’d

come from and where he’d been for almost a whole month.

“I’ve come from the Arctic Ocean,” he said. “I’ve

been to Bear Island with the Russian whalers. I sat and slept by

the tiller when they sailed out from the North Cape. Once in a

while I woke up to find the storm petrels flying around my legs.

It’s an odd bird. It flaps its wings once quickly and then holds

them out unmoving and coasts.”

“Don’t be so long-winded,” said the wind’s mother.

“And then you came to Bear Island?”

“It’s lovely there. What a floor to dance on, flat

as a plate! Half melted snow with a little moss, sharp rocks, and

skeletons of walruses and polar bears were lying there. They looked

like the arms and legs of giants, green with mold. You’d think that

the sun had never shone on them. I blew a little of the fog away so

a shack became visible. It was a house made of a wrecked ship and

covered with walrus skins. The flesh side was turned outward—it was

red and green, and there was a live polar bear growling on the

roof. I went to the beach and looked at the bird nests, looked at

the little featherless chicks who were shrieking and gaping, and

then I blew down into the thousand throats, and that taught them to

close their mouths. Furthest down the walruses were wallowing like

living entrails, or giant worms with pig heads and teeth two feet

long!”

“You tell a good story, my boy,” said his mother.

“It makes my mouth water to listen to you.”

“Then the hunt started. The harpoon went into the

walrus’ breast so steaming blood was like a fountain on the ice.

Then I thought about my own game and blew up the wind, and let my

sailing ships, the peaked mountainous icebergs, squeeze the boats

inside. Oh, how people whimpered and how they wailed, but I

whistled louder! They had to lay the dead walruses, chests, and

ropes out on the ice. I sprinkled snow flakes on them and let them

drift south with their catch on the encapsulated boats, there to

taste salt water. They’ll never return to Bear Island!”

“So you’ve done bad things then,” the wind’s mother

said.

“Others can talk about the good I’ve done,” he

said, “but here comes my brother from the west. I like him better

than any of them because he smells of the sea and brings a blessed

coldness with him.”

“Is it little Zephyr?”1 the

prince asked. “Yes, certainly it’s Zephyr,” the old woman answered,

“but he’s not so little any more. In the old days he was a lovely

boy, but that’s past now.”

He looked like a wild man, but he had a crash

helmet on so he wouldn’t get hurt. He was holding a mahogany club,

felled in an American mahogany forest. Nothing less would do!

“Where did you come from?” his mother asked.

“From the primeval forests,” he answered, “where

thorny vines make fences between each tree, where water snakes lie

in the wet grass, and where people seem unnecessary!”

“What did you do there?”

“I looked at a deep river and saw how it came

rushing from the mountains, became spray, and flew towards the

clouds where it carried the rainbow. I saw a wild buffalo swimming

in the river, carried away by the current. He rushed past a flock

of wild ducks that flew into the air where the water was tumbling

down. The buffalo had to go over the rapids. I liked that and blew

up a storm so the ancient trees went flying and became crushed to

splinters.”

“And you didn’t do anything else?” asked his old

mother.

“I turned somersaults on the savannas, petted wild

horses, and shook coconuts! Oh yes, I have stories to tell! But, as

you know, you can’t tell everything you know, old mother!” And then

he kissed his mother so she almost fell over backwards. He really

was a wild boy.

Then the South Wind came wearing a turban and a

flying Bedouin cape.

“It’s really cold in here,” he said, and threw wood

on the fire. “You can tell that North Wind was here first!”

“It’s hot enough in here to roast a polar bear,”

the North Wind said.

“You’re a polar bear yourself,” the South Wind

answered.

“Do you two want to be put into the bag?” the old

woman asked. “Sit down on that rock and tell where you’ve

been.”

“In Africa, mother,” he answered. “I’ve been on a

lion safari with the Hottentots in the land of the Kaffirs.2 Such

grass grows on those plains, green as an olive! The gnus dance

there, and the ostrich ran a race with me, but I’m faster. I came

to the desert, to the yellow sands. It looks like the bottom of the

ocean. I met a caravan! They butchered their last camel to get

water to drink, but they didn’t get much. The sun burned above

them, the sand burned below them, and there was no end to the

boundless desert. Then I romped about in the fine, loose sand and

whirled it up into big pillars. What a dance! You should have seen

how dispirited the camels were, and the merchant pulled his caftan

over his head. He threw himself down in front of me as if I were

Allah, his God. They’re buried now. A pyramid of sand is standing

over all of them. When I blow it away one day, the sun will bleach

the white bones so travelers can see that people have been there

before. Otherwise, you would never believe people had been in the

desert.”

“So you have only done evil!” his mother said.

“Into the bag with you!” and before he knew what had happened, she

had him around the waist and put him into the sack. He rolled

around on the floor, but she sat down on the bag, and he had to lie

still.

“Those are some lively boys you have!” said the

prince.

“Yes, no kidding,” she answered, “but I can manage

them. Here comes the fourth!”

It was the East Wind, and he was dressed like a

Chinaman.

“So you’re coming from that quarter,” his mother

said. “I thought you had been to the Garden of Eden?”

“I’m flying there tomorrow,” the East Wind said.

“Tomorrow it’ll be a hundred years since I’ve been there. I’m

coming from China now where I was dancing around porcelain towers

so all the bells were ringing. Down on the street, the officials,

from the first to the ninth rank, got a beating. Bamboo rods were

broken on their shoulders, and they cried out: ‘many thanks, my

fatherly benefactor,’ but they didn’t mean it, and I rang the bells

and sang tsing, tsang, tsu!”

“You’re a blow-hard about it,” said the old woman.

“It’s a good thing that you’re going to the Garden of Eden tomorrow

since that always helps your manners. Drink deeply from the spring

of wisdom and bring a little bottle full home to me!”

“I’ll do that,” the East Wind said. “But why have

you put my brother from the south into the bag? Let him out! He’s

going to tell me about the bird phoenix—the bird that the princess

in the Garden of Eden always wants to hear about every hundred

years when I visit. Open the bag, dearest mother, and I’ll give you

two pockets full of fresh green tea that I picked on the

spot.”

“Well, for the sake of the tea and because you’re

my pet child, I’ll open the sack.” She did, and the South Wind

crept out, but the wind was out of his sails since the foreign

prince had witnessed it.

“Here is a palm leaf for the princess,” the South

Wind said. “That leaf was given to me by the old bird phoenix, the

only one who existed in the world. With his beak he inscribed his

whole life story there, the hundred years he lived. Now she can

read it for herself. I saw how the phoenix set his nest on fire

himself and burned up like a Hindu widow. Oh, how the dry branches

crackled, what smoke and smells! At last it all went up in flames.

The old phoenix lay in ashes, but his egg lay glowing red in the

fire. It cracked with a big bang, and the young bird flew out. Now

he is the ruler of all the birds, and the only phoenix in the

world. He bit a hole in the palm leaf I gave you as a greeting to

the princess.”

“Now we have to have something to eat,” the Winds’

mother said, and they all sat down to eat roasted venison. The

prince sat beside the East Wind, and they soon became fast

friends.

“Tell me something,” said the prince, “who is this

princess you all talked so much about, and where is the Garden of

Eden?”

“Ho, ho,” the East Wind said. “If you want to go

there, fly with me tomorrow. But I must tell you, no human has been

there since Adam and Eve’s time. You surely know about them from

your Bible history?”

“Of course!” the prince said.

“At the time they were banished, the Garden of Eden

sank down into the earth, but it kept its warm sunshine, its mild

air, and all its splendor. The Queen of the Fairies lives there,

and there too lies the Island of Bliss, where death never comes.

It’s a lovely place to be! Climb on my back in the morning, and

I’ll take you along. I think it can be done. But now you have to be

quiet because I want to sleep.”

And then they all slept.

Early in the morning the prince woke up and was not

just a little puzzled at already being high up over the clouds. He

was sitting on the back of the East Wind, who was faithfully

holding on to him. They were so high in the air that fields and

forests, rivers and lakes looked like they would on a big

illuminated map.

“Good morning,” the East Wind said. “You might as

well sleep a bit more because there’s not much to see here on the

flat lands below us. Unless you want to count churches! They’re

standing like chalk marks on the green board.” The green board was

what he called the fields and meadows.

“It’s too bad I didn’t get to say good bye to your

mother and brothers,” the prince said.

“When you’re asleep, you’re excused,” said the East

Wind, and then they flew even faster—you could hear it by the

branches and leaves rustling through the tops of the forests when

they flew over them. You could hear it by the sea and

lakes—wherever they flew the waves broke higher, and the big ships

bowed deeply down in the water like swimming swans.

Towards evening when it got dark, it was fun to see

the big cities. Lights were burning down there in different places.

It was just like when you burn a piece of paper and see all the

little sparks of fire blinking and disappearing like children

coming out from school and running in all directions. And the

prince clapped his hands, but the East Wind told him to stop that

and hold on; otherwise, he could easily fall down and find himself

hanging on a church steeple.

The eagles in the dark forest flew quickly, but the

East Wind flew more quickly. The Cossack on his little horse rushed

across the plains, but the prince rushed faster.

“Now you can see the Himalayas,” said the East

Wind. “The highest mountain in Asia is there. We’ll be at the

Garden of Eden soon.” They veered to the south, and soon there was

a smell of spices and flowers. Figs and pomegranates were growing

wild, and the wild grapevines were full of blue and red grapes.

They landed there and stretched on the soft grass where the flowers

nodded to the wind as if they wanted to say, “welcome back.”

“Are we in the Garden of Eden now?” the prince

asked.

“Certainly not,” said the East Wind, “but we’ll

soon be there. See that wall of rock over there and that big cave

where the grapevines are hanging like big green curtains? We’re

going through there. Wrap your coat around you. The sun is shining

warmly here, but just a step away it’s freezing cold. That bird

that’s flying past the cave has one wing out here in the warm

summer and the other in there in the cold winter.”

“So that’s the way to the Garden of Eden?” the

prince asked.

They went into the cave. Oh, it was freezing cold,

but it didn’t last long. The East Wind spread out his wings, and

they shone like the clearest fire. But what caves! Big boulders

hung over them in the most fantastic configurations, and water was

dripping from them. Sometimes it was so narrow that they had to

creep on their hands and knees, sometimes so wide and open as if

they were out in the open air. It was like a funeral chapel in

there with silent organ pipes and petrified banners.

“I guess we’re taking death’s path to the Garden of

Eden,” said the prince, but the East Wind didn’t say a word, just

pointed ahead where a beautiful blue light was beaming towards

them. The boulders above became more and more a mist and finally

were as clear as a white cloud in moonlight. Then they entered the

loveliest mild atmosphere, as fresh as in the mountains, as

fragrant as in a valley of roses.

There was a river running there as clear as the air

itself, and the fish were like silver and gold. Crimson eels that

shot off blue sparks with every movement were sparkling in the

water, and the wide water lily leaves were the colors of the

rainbow. The flower itself was a burning red-yellow flame fed by

the water, just like oil always gets the lamp to burn. A solid

bridge of marble, so artistically and finely carved as if it were

made of lace and glass beads, led over the water to the Island of

Bliss where the Garden of Eden was blooming.

The East Wind took the prince in his arms and

carried him over. Flowers and leaves were singing the most

beautiful songs of his childhood there, but far more lovely than

any human voice can sing.

Were they palm trees or gigantic water plants

growing there? The prince had never before seen such succulent

large trees. Creeping plants were slung in big garlands through the

trees like you only see them pictured with colors and gold in the

margins or entwined in the initial letters of medieval manuscripts.

They were a strange combination of birds, flowers, and twisting

vines. Close by in the grass was a flock of peacocks with their

radiant widespread tails. Or so they seemed, but when the prince

touched them, he discovered that they weren’t animals but plants.

They were big burdock leaves that were shining like beautiful

peacock tails. Tame lions and tigers ran like lithe cats through

the green hedges that smelled like apple blossoms, and the wild

wood pigeon, shining like the most perfect pearl, flapped its wings

on the lion’s mane. The antelope, usually so shy, stood nodding its

head as if it wanted to play too.

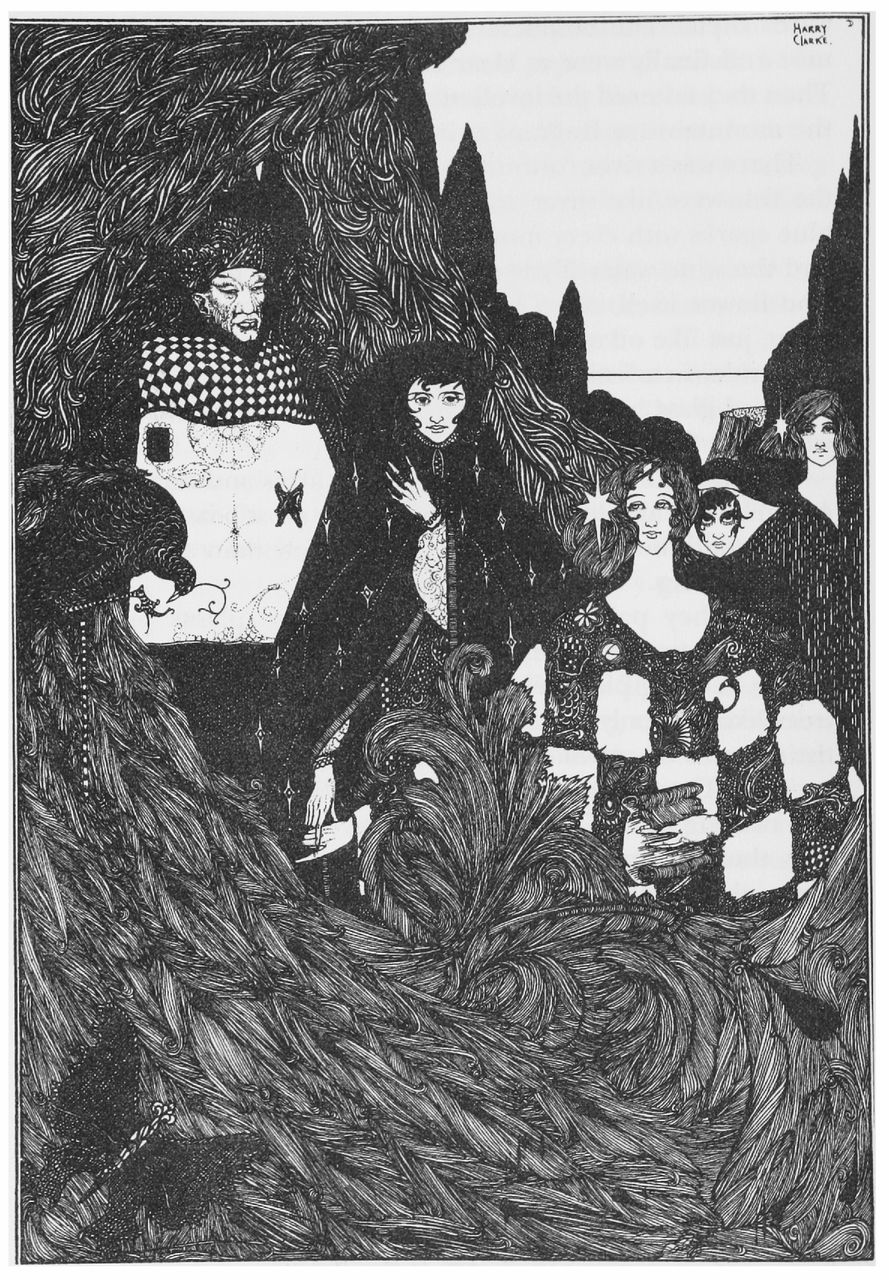

Then the fairy of paradise came. Her clothes were

shining like the sun, and her face was gentle as a happy mother’s

when she is pleased with her child. She was very young and

beautiful, and the loveliest girls, each with a shining star in her

hair, were following her.

She took the prince by the hand and led him

into her castle.

The East Wind gave her the leaf from the phoenix,

and her eyes sparkled with joy. She took the prince by the hand and

led him into her castle where the walls were the colors of the most

radiant tulips held up to the sun. The ceiling itself was a big

brilliant flower, and the more you stared up at it, the deeper the

calyx appeared. The prince went to the window and looked through

one of the panes, and he saw the tree of knowledge with the snake

and Adam and Eve standing close by. “Weren’t they banished?” he

asked, and the fairy smiled and explained to him that time had

burned an image in each pane of the window, but not as you usually

see pictures. These had life in them. The leaves of the trees

moved, people came and went, as in a reflection. And he looked

through a different pane, and there was Jacob’s dream where the

ladder went clear up into heaven, and angels with huge wings were

floating up and down. Everything that had happened in this world

lived and moved in the glass panes. Only time could create such

inspired paintings.

The fairy smiled and led him into a chamber with a

big high ceiling. The walls appeared as transparent paintings, each

face on them more lovely than the next. There were millions of

these happy ones who smiled and sang together with one melody.

Those high on top were so small that they appeared smaller than the

tiniest rosebud when drawn as a dot on a piece of paper. In the

middle of the chamber stood a big tree with superb hanging

branches. Big and small gilded apples hung like oranges between the

green leaves. It was the Tree of Knowledge, from which Adam and Eve

had eaten. There was a red drop of dew dripping from each leaf; it

was as if the tree were crying tears of blood.

“Let’s get into the boat,” said the fairy. “We’ll

enjoy refreshments out on the water. The boat pitches back and

forth although it doesn’t leave the spot, and all the countries of

the world will pass before our eyes.” And it was marvelous to see

how the entire coast moved. First came the high snow-covered Alps,

with clouds and black evergreens. The horn sounded deep and

mournfully, and the shepherd yodeled sweetly in the valley. Then

the banana trees bent their long, hanging branches down over the

boat. Coal black swans swam on the water, and the strangest animals

were seen on the beaches—this was Australia, the fifth continent of

the world, gliding by with a view of the blue mountains. You could

hear the singing of medicine men and see the wild men dancing to

the sound of drums and bone flutes. The pyramids of Egypt sailed by

with their tops in the clouds, along with overturned pillars and

sphinxes half buried in sand. The northern lights burned over the

glaciers of the north. It was a fire works display that no one

could match. The prince was ecstatic. Of course he saw a hundred

times more than we can describe here.

“Can I stay here forever?” he asked.

“That depends on you,” the fairy answered. “As long

as you don’t act like Adam, and let yourself be tempted to do

what’s forbidden, you can stay here forever.”

“I won’t touch the apples on the Tree of

Knowledge,” the prince said. “There are thousands of fruits here

just as lovely as they are.”

“Test yourself, and if you aren’t strong enough,

then return with the East Wind, who brought you here. He’s flying

back now and won’t return for a hundred years. For you that time

will pass as if it were only a hundred hours, but it’s a long time

for temptation and sin. Every evening when I leave you, I must call

you to ‘follow me.’ I’ll wave you to follow, but you must stay

behind. Don’t come with me because then every step will increase

your longing. You’ll come into the chamber where the Tree of

Knowledge grows. I sleep under its fragrant hanging branches.

You’ll bend over me, and I’ll smile, but if you kiss my lips,

paradise will sink deep into the earth, and it will be lost to you.

The sharp winds of the desert will whirl around you, and cold rain

will drip from your hair. Sorrow and troubles will be your

fate.”

“I’ll stay here!” the prince said, and the East

Wind kissed him on the forehead and said, “Be strong, and we’ll

meet here again in a hundred years. Farewell! farewell!” The East

Wind spread out his enormous wings. They shone like the flash of

heat lightning at harvest time, or the northern lights on cold

winter nights. “Farewell! farewell!” sounded from the flowers and

trees. Storks and pelicans flew along in rows, like a waving

ribbon, and followed to the border of the garden.

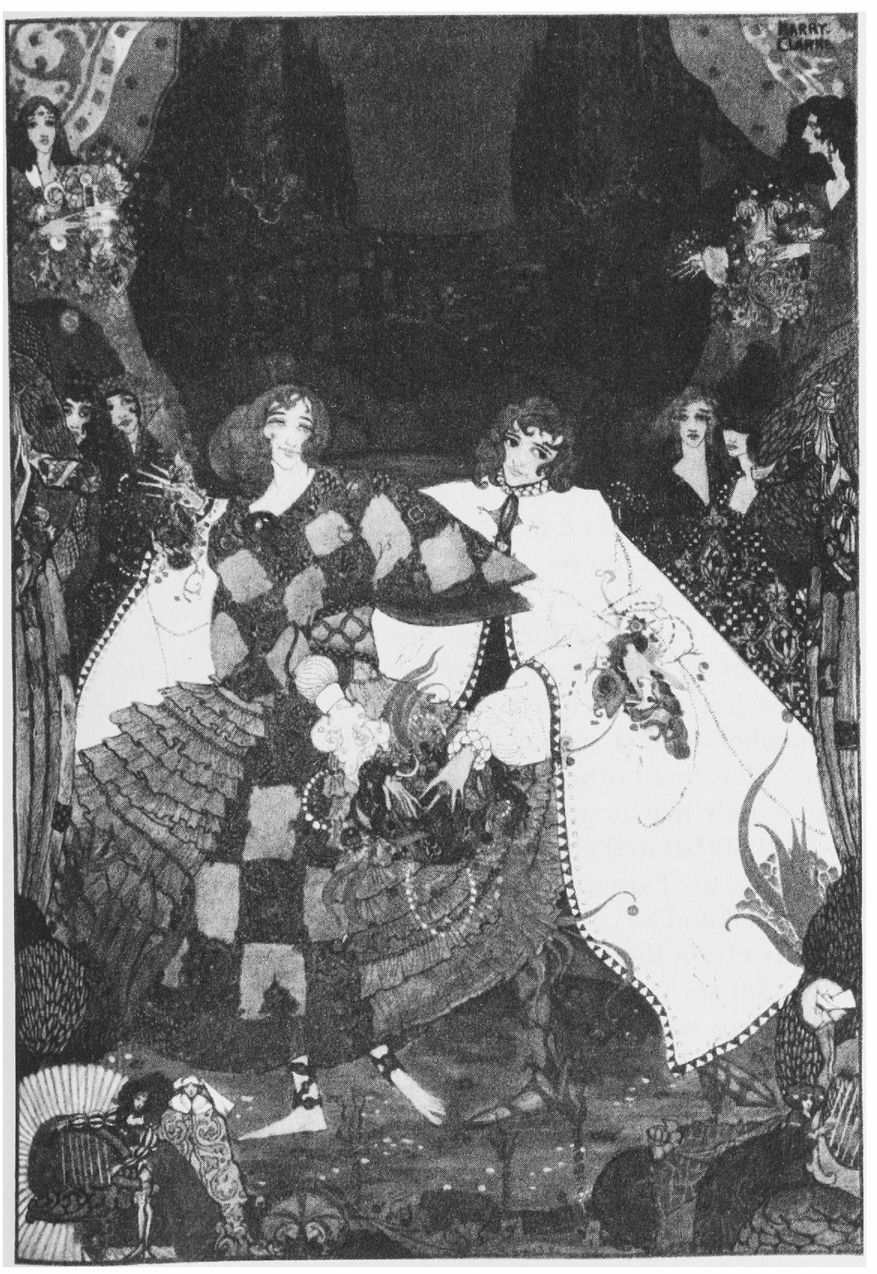

“Now our dances will begin,” said the

fairy.

“Now our dances will begin,” said the fairy. “At

the end of our dance, you’ll see me waving at you as the sun sinks,

and you’ll hear me call to you: ‘follow along!’ But don’t do it!

Every evening for a hundred years I’ll repeat this, and every time

it’s over you’ll gain more strength. Finally, you’ll never think

about it. Tonight is the first time, and now I have warned

you!”

And the fairy led him into a big chamber with white

transparent lilies. The yellow stamen in each one was a little gold

harp that played like a stringed instrument and with tones of

flutes. The most beautiful slender girls floated about, dressed in

waving gauze so you could see their lovely limbs. They swayed in

the dance and sang about how splendid it was to live—that they

would never die, and that the Garden of Eden would blossom

forever.

The sun went down. The whole sky turned to gold and

gave the lilies the cast of the most beautiful rose, and the prince

drank of the frothing wine that the girls gave him. He felt

happiness like never before, and then he saw how the back of the

chamber opened up, and the Tree of Knowledge was standing in a glow

that burned his eyes. The song from there was soft and lovely, like

his mother’s voice, and it was as if she sang, “My child! My

beloved child!”

Then the fairy waved and called so fondly, “Follow

me, follow me!” and he rushed towards her, forgot his promise,

forgot it already on the first evening, and she waved and smiled.

The fragrant spicy perfume of the air grew stronger; the tones of

the harps more beautiful; and it was as if the millions of smiling

faces in the chamber where the tree grew nodded and sang, “You

should know everything! Man is the master of the earth.” And he

thought there was no longer blood dripping from the leaves of the

Tree of Knowledge, but red sparkling stars. “Follow me, follow me,”

sang the trembling tones, and with every step the prince’s cheeks

burned hotter, and his blood pounded harder. “I must,” he said,

“it’s not a sin, it can’t be! Why not follow beauty and joy? I want

to see her sleeping. Nothing is lost as long as I don’t kiss her,

and I won’t do that. I’m strong, and have a firm will.”

And the fairy threw aside her shining fancy dress,

bent the branches back, and a second later she was hidden

within.

“I haven’t sinned yet,” said the prince, “and I

won’t do it either.” He pulled the branches aside. She was already

sleeping, lovely as only the fairy in the Garden of Eden can be,

and she smiled in her sleep. He leaned down over her and saw tears

tremble among her eyelashes.

“Are you crying over me?” he whispered. “Don’t cry,

you beautiful woman. Now I finally understand the happiness of

paradise. It’s rushing through my blood, through my thoughts. I

feel in my earthly body the cherub’s power and eternal life. Let me

suffer eternal night—a minute like this is richness enough.” And he

kissed the tears on her eyes, and his mouth moved to hers—

Then there was a clap of thunder so deep and

terrible as had never been heard before, and everything collapsed.

The beautiful fairy and the blooming paradise sank, sank so deeply,

so deeply. The prince saw it sink in the black night; it shone like

a little shining star far in the distance. A deathly cold shot

through his limbs. He closed his eyes and lay a long time as if

dead.

Cold rain fell on his face, the sharp wind blew

around his head, and he came to himself again. “What have I done?”

he sighed. “I’ve sinned like Adam! Sinned so that the Garden of

Eden has sunk way down there.” And he opened his eyes. He could

still see the star, far away, the star that sparkled like the

sunken paradise—It was the morning star in the sky.

He stood up and saw that he was in the big forest

close to the Cave of the Winds, and the Winds’ mother sat by his

side. She looked angry and lifted her arm in the air.

“Already on the first evening!” she said, “I might

have known. If you were my son, I’d put you into the bag right

now!”

“He’ll go there,” said Death, who was a strong, old

man with a scythe in his hand and with big black wings. “He’ll come

to his coffin, but not yet. I’ll just make a note of him, and let

him wander around in the world for a while yet. He can atone for

his sin, become good and better!-I’ll come one day. When he least

expects it, I’ll put him into a black coffin, set it on my head,

and fly up towards the star. The Garden of Eden blossoms there too,

and if he is good and pious, then he’ll enter there. But if his

thoughts are evil and his heart is still full of sin, he’ll sink

deeper in his coffin than the Garden of Eden sank, and I’ll only

fetch him again every thousand years, either to sink deeper yet or

to be taken to the star—that sparkling star up there!”

NOTES

1 The

west wind of Greek mythology. Zephyr (or Zephyrus) is the brother

of Boreas (the North Wind) and the father of Achilles’ horses

Xanthus and Balius.

2

Present-day Zimbabwe and South Africa. The name “Kaffir” (from the

Arabic for “non-believer”) was given by the Arabs to the native

races of the east coast of Africa.