THE WILD SWANS

FAR AWAY FROM HERE, where the swallows fly during

the winter, there lived a king who had eleven sons and one

daughter, Elisa. The eleven brothers, who were princes, went to

school with stars on their breasts and swords by their sides. They

wrote on gold slates with diamond pencils and knew their lessons by

heart, and you could tell right away that they were princes. Their

sister Elisa sat on a little footstool of plate glass and had a

picture book that had cost half the kingdom.

Oh, those children had a good life, but it wasn’t

going to stay that way!

Their father, who was the king of the entire

country, married an evil queen, who was not good to the poor

children; they noticed it already on the first day. There was a big

celebration at the castle, and the children were playing house, but

instead of the cookies and baked apples they usually got plenty of,

she gave them sand in a teacup and told them to pretend it was

something else.

The next week she farmed little sister Elisa out to

some peasants in the country, and it wasn’t long before she was

able to get the king to imagine all sorts of wicked things about

the princes so that finally he didn’t care about them

anymore.

“Fly out in the world and take care of yourselves!”

said the evil queen. “Fly as great voiceless birds!” but she wasn’t

able to make it quite as bad as she wanted—they became eleven

lovely wild swans. With a strange cry they flew out of the castle

windows and over the park and the forest.

It was still early morning when they flew over the

peasant’s cottage where their sister Elisa was sleeping. They

hovered over the roof, twisted their long necks, and flapped their

wings, but no one saw or heard them. They flew away again, high up

towards the clouds and far away into the wide world and into a big

dark forest that stretched all the way to the sea.

Poor little Elisa stood in the peasant’s cottage

playing with a green leaf because she didn’t have any other toys.

She pierced a hole in the leaf and peeked up at the sun through it,

and it was as if she saw her brothers’ clear eyes, and each time

the sunshine hit her cheek, she thought about their many

kisses.

One day passed like another. When the wind blew

through the big rose hedges outside the house, it whispered to the

roses, “Who can be more beautiful than you?” but the roses shook

their heads and answered, “Elisa.” And when the old woman sat by

the door reading her hymnal on Sundays, the wind turned the pages

and said to the book, “Who can be more pious than you?” “Elisa,”

said the hymnal, and what the roses and the hymnal said was the

solemn truth.

When she was fifteen years old, she was to return

home, and as soon as the queen saw how beautiful she was, she

became angry and hateful to her. She would have liked to turn Elisa

into a wild swan, like she did to her brothers, but she didn’t dare

do it right away since the king wanted to see his daughter.

Early in the morning the queen went into her

bathroom, which was built of marble and was decorated with soft

cushions and the loveliest carpets. She took three toads, kissed

them, and said to the first, “Sit on Elisa’s head when she gets

into the bath, so that she will become sluggish, like you.”

“Sit on her forehead,” she said to the second one,

“so she will become ugly like you, and her father won’t recognize

her.”

“Sit on her heart,” she whispered to the third.

“Give her a bad disposition, so she’ll suffer from it.”

Then she put the toads into the clear water, which

immediately took on a greenish hue, called Elisa, undressed her,

and had her step into the bath, and as she went under the water,

the first toad sat on her hair, the second on her forehead, and the

third on her breast, but Elisa didn’t seem to notice. As soon as

she rose up, there were three red poppies floating on the water. If

the animals hadn’t been poisonous and kissed by the witch, they

would have been changed to red roses, but they became flowers

anyway by resting on her head and on her heart. She was too pious

and innocent for the black magic to have any power over her.

When the evil queen saw this, she rubbed walnut oil

on Elisa so she became dark brown. Then she spread a stinking salve

over the beautiful face and left her lovely hair tangled and

matted. It was no longer possible to recognize the lovely Elisa at

all.

When her father saw her, he became quite alarmed

and claimed that she wasn’t his daughter. No one else would

acknowledge her either, except the watchdog and the swallows, but

they were just poor animals and didn’t count.

Poor Elisa wept and thought about her eleven

brothers, all of whom were gone. She crept sadly out of the castle

and wandered the whole day over moor and meadow and into the big

forest. She didn’t know where she wanted to go, but she felt so sad

and longed for her brothers, who had been chased out into the world

like her. Now she would search them out and find them.

She had only been in the woods for a short time

before night fell. She had wandered clear away from the path, so

she lay down on the soft moss, said her prayers, and rested her

head on a stump. It was so quiet, the air was so mild, and around

about her in the grass and on the moss there were hundreds of

glowworms shining like green fire. When she gently touched one of

the branches with her hand, the shining insects fell down to her

like falling stars.

All night she dreamed about her brothers. They were

children playing again, writing with the diamond pencil on golden

slates, and looking at the lovely picture book that had cost half

the kingdom. But they didn’t draw only circles and lines on the

slates, like before, rather they wrote about the most daring deeds

that they had done, everything they had experienced and seen.

Everything in the picture book was alive. Birds sang and the people

came out of the book and talked to Elisa and her brothers, but when

she turned the page, they leaped back in again, so that the

pictures wouldn’t get mixed up.

When she awoke, the sun was already high in the

sky. She couldn’t see it because the branches of the tall trees

were spread across the sky, but the rays danced up there in the

treetops like a fluttering veil of gold. All the green plants gave

off a fragrance, and the birds almost perched on her shoulders. She

heard water splashing from a great many large springs that all

pooled into a pond with a lovely sand bottom. All around the pond

bushes were growing densely, but in one spot the deer had cleared a

big opening, and Elisa was able to get to the water, which was so

clear that if the wind hadn’t stirred the branches and bushes so

they moved, you would have thought that they were painted on the

bottom, so vividly was every leaf reflected there, both in sunshine

and in shade.

When she saw her own face, she was frightened

because it was so brown and ugly, but when she took water in her

little hand and rubbed her eyes and forehead, the white skin shone

through again. Then she took off all her clothes and went into the

refreshing water, and there was no more beautiful princess

anywhere.

When she was dressed and had braided her long hair,

she went to the bubbling spring, drank from the hollow of her hand,

and wandered further into the forest, not knowing where she was

going. She thought about her brothers and about the good Lord, who

wouldn’t desert her. He let the wild crab apples grow, to feed the

hungry, and He showed her such a tree with branches heavy with

fruit. She had her dinner here, propped up the branches of the

tree, and then walked into the darkest part of the forest. It was

so quiet that she could hear her own footsteps, hear every little

shriveled leaf that crunched under her feet. Not a bird could be

seen, and not a ray of sunshine could shine through the big thick

tree branches. The tall trunks stood so close together that when

she looked straight ahead, it was as if she had a fence of thick

posts all around her. Oh, here was a loneliness such as she’d never

known!

The night became pitch dark, and there was not a

single little glowworm shining on the moss. Sadly she lay down to

sleep. Then she thought that the tree branches above her parted,

and the Lord with gentle eyes looked down on her, and small angels

peered out over his head and under his arms.

When she awoke in the morning she didn’t know if it

had been a dream or if it had really happened. After walking a

short way, she met an old woman who had some berries in her basket.

The old woman gave her some of these, and Elisa asked if she had

seen eleven princes riding through the forest.

“No,” said the old woman, “but yesterday I saw

eleven swans with gold crowns on their heads swimming in the river

not far from here.”

And she led Elisa a little further to a steep slope

with a river winding below it. The trees on each bank stretched out

their long leafy branches towards each other, and wherever they

couldn’t reach with natural growth, they had torn their roots out

from the soil and were leaning out over the water with branches

woven together. Elisa said goodbye to the old woman and walked

alongside the river until it flowed out onto a wide open

shore.

The whole beautiful ocean lay there in front of the

young girl, but neither a sail nor a boat could be seen out there.

How was she to get any further? She looked at all the innumerable

little stones on the shore; the water had polished them smooth.

Glass, iron, stone—everything that was washed up on the beach had

been shaped by water, water that was softer still than her white

hand. “They roll tirelessly, and so they smooth out the roughness;

I’ll be just as tireless! Thank you for your wisdom, you clear

rolling waves. My heart tells me that some day you’ll carry me to

my dear brothers.”

Lying in the washed-up seaweed there were eleven

white swan feathers that she gathered in a bouquet. There were

water drops on them, but no one could tell if it was dew or tears.

It was lonely there on the beach, but she didn’t feel it since the

ocean changed constantly—more in a few hours than a lake would

change in a whole year. If a big black cloud came over, it was as

if the ocean said, “I can also look dark,” and then the wind blew,

and the waves showed their white caps. If the clouds were glowing

red and the wind was sleeping, then the sea was like a rose petal.

First it was green, then white, but no matter how quietly it

rested, there was always a slight movement by the shore; the water

swelled softly, like the chest of a sleeping child.

Just before the sun went down, Elisa saw eleven

white swans with gold crowns on their heads flying towards land.

They were gliding across the sky one after the other like a long

white ribbon. Elisa climbed up on the slope and hid behind a bush

while the swans landed close by her and flapped with their great

white wings.

After the sun had set, the swan skins suddenly

slipped off, and there stood eleven handsome princes, Elisa’s

brothers. She gave a loud cry, because even though they had changed

a lot, she knew that it was them. Indeed, she felt that it must be

them and ran into their arms, calling them by name, and they became

so happy when they saw and recognized their little sister, who had

grown so big and beautiful. They laughed and they cried, and soon

told each other how badly their step-mother had treated them

all.

The eldest brother said, “We brothers fly as wild

swans so long as the sun is up, but when it sets, our human shapes

are returned to us. That’s why we always have to be careful to be

on land at sunset because, if we were to be flying up in the

clouds, then we would fall to the ground. We don’t live here, but

in a land just as beautiful as this one on the other side of the

sea. It’s far far away, and we have to cross the ocean. There is no

island on our route where we can spend the night except a lonely

little rock that sticks up way out in the middle of the sea. It’s

so small that we have to rest there side by side. In high seas the

waves spray over us, but still we thank God for it. We spend the

night there in our human shape, and without it we could never visit

our dear fatherland because it takes two of the longest days of the

year to make the flight. We can only visit our homeland once a

year, and we don’t dare stay more than eleven days. We fly over

this huge forest, from where we can see the castle where we were

born, and where father lives. We can see the high tower of the

church, where mother is buried.—We feel related to the trees and

bushes here. The wild horses run over the plains here, as we saw

them in our childhood. The coal-burners still sing the same old

songs here that we danced to as children. Our fatherland is here.

We’re drawn here, and here we have found you, dear little sister!

We can only stay two more days, and then we have to fly over the

sea to that lovely country that isn’t our native land. How can we

bring you with us? We have neither ship nor boat.”

“How can I save you?” their sister responded.

They spoke together almost the whole night and

slept only a few hours.

Elisa awoke to the sound of swans’ wings whistling

over her. Her brothers were once again transformed, and they flew

in a big circle and finally far away, but one of them, the

youngest, stayed behind and laid his head in her lap. She patted

his white wings, and they spent the whole day together. Towards

evening, the others came back, and when the sun went down, they

stood there in their natural form.

“We have to fly away tomorrow and don’t dare come

back for a whole year, but we can’t leave you! Do you have the

courage to come with us? My arm is strong enough to carry you

through the forest. Together we should have strong enough wings to

fly with you across the sea.”

“Yes! Take me along!” said Elisa.

They spent the whole night braiding a net of the

supple willow bark and thick rushes, and it was of great size and

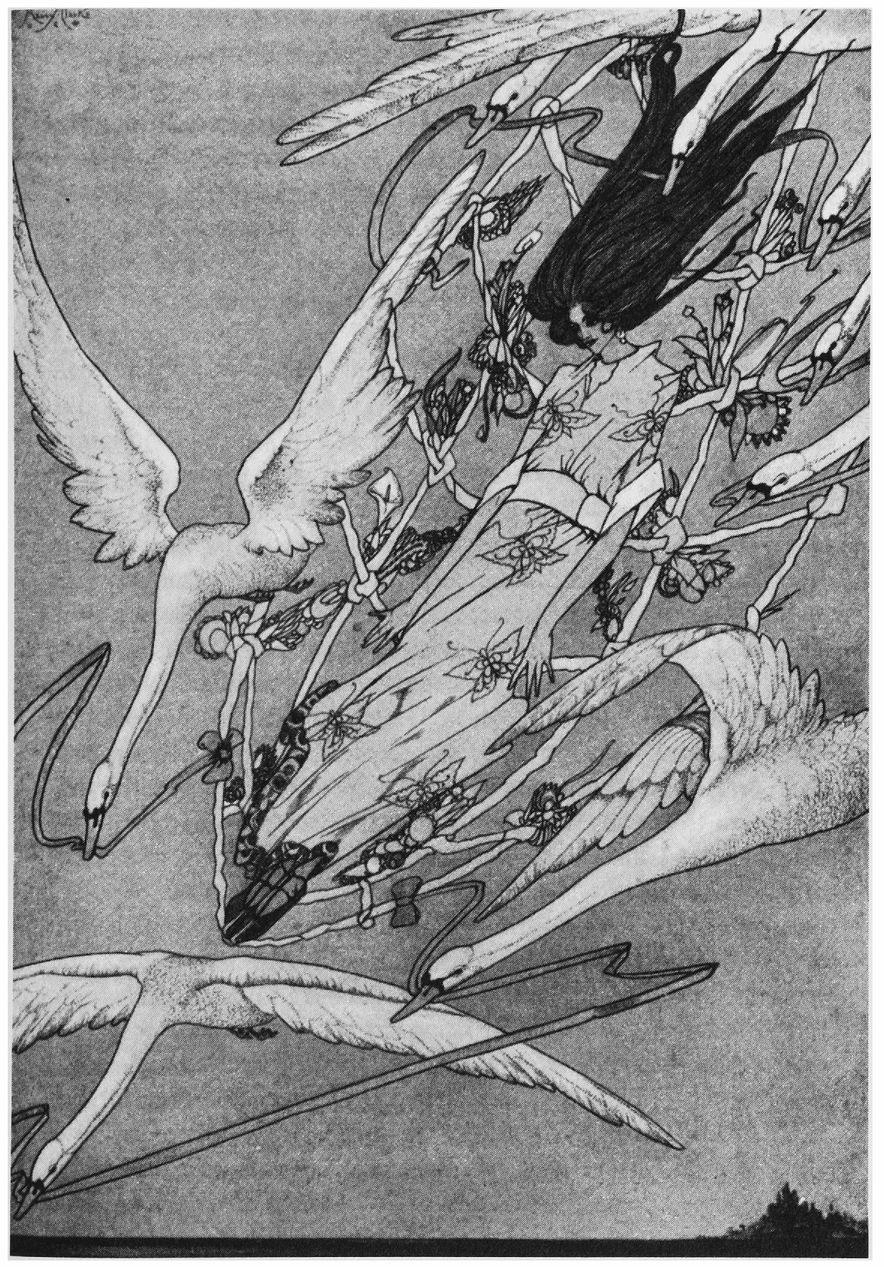

strength. Elisa laid down on this, and after the sun came up, and

the brothers were changed to swans, they took hold of the net with

their beaks and flew high up towards the clouds with their dear

sister, who was still sleeping. When the rays of the sun shone on

her face, one of the swans flew over her head so that his wide

wings shaded her.

They were far from land when Elisa woke up. She

thought she was still dreaming because it was so strange for her to

be carried high in the air above the ocean. By her side lay a

branch with delicious ripe berries and a bunch of tasty roots. Her

youngest brother had gathered them and placed them there for her,

and she smiled her thanks at him. She knew that it was he who was

flying right above her head, shading her with his wings.

They were so high up that the first ship they saw

under them looked like a white seagull floating on the water. There

was a huge cloud behind them like a mountain, and on it Elisa could

see the enormous shadows of herself and the eleven swans as they

flew. It was a picture more magnificent than anything she had seen

before, but as the sun rose higher and the cloud receded behind

them, the floating shadow picture disappeared.

All day they flew, like a rushing arrow

through the air.

All day they flew, like a rushing arrow through the

air, but it was slower than usual since they had to carry their

sister. A storm was gathering, and evening was coming. Anxiously,

Elisa saw the sun sink, and the lonely rock in the sea was not in

sight. It seemed to her that the swans were strengthening their

wing strokes. Alas! It was her fault that they weren’t moving

faster! When the sun set, they would change into men, fall into the

sea, and drown. Deep in her heart she said a prayer to the Lord,

but she still couldn’t see the rock. The black cloud came closer,

and strong gusts of wind told of the storm’s approach. The clouds

came rolling towards them like a single big threatening wave of

lead, and lightning bolt followed lightning bolt.

The sun was just at the rim of the sea, and Elisa’s

heart trembled. The swans shot downward so quickly that she thought

she was falling—then they glided again. The sun was halfway down in

the sea when she first saw the little rock below her. It didn’t

look any bigger than a seal sticking its head up from the water.

The sun sank quickly and was now no bigger than a star. Then her

foot felt the hard rock as the sun went out like the last spark in

a piece of burning paper. She saw her brothers standing around her,

arm in arm, but there wasn’t room for anyone else. The sea crashed

against the rock and splashed over them like a cloudburst of rain.

The sky was shining like never-ending fire, and clap after clap of

thunder rolled by, but the sister and her brothers held hands and

sang a hymn, which gave them comfort and courage.

At dawn the air was clear and still, and as soon as

the sun came up, the swans flew away from the rock with Elisa.

There was still a high sea, and when they were high in the air, the

white foam on the dark green sea looked like millions of swans

floating on the water.

When the sun climbed higher, Elisa saw ahead of

her, half floating in the air, a mountainous land with shining

glaciers on the mountains, and in the middle was a mile-long castle

with one bold colonnade on top of the other. Below there were

waving palm forests and gorgeous flowers big as mill wheels. She

asked if that was their destination, but the swans shook their

heads. What she saw was a mirage, Fata

Morgana’s1 lovely sky castle that was

constantly changing, and they didn’t dare bring humans there. As

Elisa stared at it, the mountain, forests, and castle collapsed and

twenty splendid churches stood there, all alike, with high steeples

and arched windows. She thought she heard the organ playing, but it

was the ocean she heard. When she was quite close to the churches,

they changed to an entire fleet of ships that sailed below her. She

looked down, and it was only sea-fog chasing across the water. She

was watching an ever-changing scene, and then she saw the real

country that was their destination. There were lovely blue

mountains with cedar forests, towns and castles. Long before

sunset, she was sitting on a mountain in front of a big cave,

overgrown with fine green twining plants, which looked like

embroidered carpets.

“Now we’ll see what you dream about here tonight,”

said the youngest brother and showed her to her bedroom.

“I wish I would dream about how I could rescue you

all!” she said, and this thought occupied her so vividly that she

prayed fervently to God for help. Even in sleep she continued her

prayer; and it seemed to her that she flew high up in the air to

Fata Morgana’s sky castle, and a fairy came towards her,

lovely and glittering, but she looked exactly like the old woman

who had given her berries in the forest and told her about the

swans wearing the gold crowns.

“Your brothers can be rescued,” she said, “if you

have the courage and perseverance. It’s true that the sea is softer

than your fine hands and can shape the hard stones, but it doesn’t

feel the pain your fingers will feel. It has no heart and doesn’t

suffer the dread and terror you must tolerate. Do you see this

stinging nettle I’m holding in my hand? Many of these grow around

the cave where you’re sleeping. Only those and those that grow on

the graves in the churchyard can be used—take note of that. You

have to pick them, although they will burn your skin to blisters.

Then you must tramp the nettles with your feet to get flax, and

with that you must spin and knit eleven thick shirts with long

sleeves. Throw these over the eleven wild swans, and the spell will

be broken. But remember this: from the moment you begin this work

and until the day it is finished you cannot speak, even if your

work takes years. The first word you speak would be like a dagger

in your brothers’ hearts, and it would kill them. Their lives hang

upon your tongue. Pay attention to all that I’ve told you!”

And she touched Elisa’s hand with the nettle, which

like a burning fire, woke her up. It was bright day, and right next

to where she had been sleeping, lay a nettle like the one she had

seen in her dream. Then she fell on her knees and thanked God, and

went out of the cave to begin her work.

With her fine hands, she reached down into the

nasty nettles, which were like scorching fire. They burned big

blisters on her hands and arms, but she bore it gladly, to rescue

her dear brothers. And so she broke each nettle with her bare feet

and spun the green flax.

When the sun went down, her brothers came, and they

were frightened to find her so silent. They thought their evil

step-mother had cast a new spell, but when they saw her hands, they

realized what she was doing for their sakes, and the youngest

brother burst into tears. Wherever his tears fell, the pain left

her, and the burning blisters disappeared.

She worked all night because she could have no rest

until she had saved her beloved brothers. All the next day, while

the swans were away, she sat there alone, but time had never flown

so quickly. One shirt was already finished, and she started on the

next one.

Then she heard a hunting horn echo through the

hills, and it scared her. The sound came closer, and she heard dogs

barking. Frightened, she ran into the cave and wound the nettles

and her knitting into a bundle and sat down on it.

Just then a big dog sprang from the thicket, and

then another and another; they barked loudly and ran back and

forth. Within a few minutes all the hunters were standing outside

the cave, and the most handsome of them all was the king of the

country. He went into the cave, and never had he seen a more

beautiful girl than Elisa.

“How did you get here, you beautiful child?” he

asked.

Elisa shook her head. She didn’t dare speak, of

course, since her brothers’ lives and safety were at stake, and she

hid her hands under her apron, so the king would not see what she

was suffering.

“Come with me!” he said, “You can’t stay here! If

you’re as good as you are beautiful, I’ll dress you in silk and

velvet and set a gold crown on your head, and you’ll live in my

richest castle.”

He lifted her up onto his horse, and she cried and

wrung her hands, but the king said, “I only want your happiness.

Some day you’ll thank me for this.” Then he galloped away through

the hills with her in front of him on the horse, and the hunters

followed after them. As the sun was setting, the magnificent royal

city with its churches and domes was lying before them, and the

king led her into the castle, where enormous fountains splashed

under the high ceilings in rooms of marble. The walls and ceilings

were decorated with paintings, but she had no eye for them. She

cried and grieved, and passively let the women dress her in royal

clothing, braid pearls in her hair, and draw fine gloves over her

burned fingers.

When she stood there in all her glory, she was so

dazzlingly beautiful that the court bowed down deeply to her, and

the king chose her for his queen, even though the arch-bishop shook

his head and whispered that the beautiful forest maiden must be a

witch, who had bedazzled their eyes and bewitched the king’s

heart.

But the king didn’t listen to him. Instead he had

the musicians play and had the most splendid dishes served. The

most beautiful girls danced around Elisa, and she was led through

fragrant gardens into magnificent chambers, but not a smile crossed

her lips, or appeared in her eyes, where sorrow seemed to have

taken up eternal residence. Then the king opened a door to a tiny

room, close by her bedroom; it was decorated with expensive green

carpets and resembled the cave where she had been. The bundles of

flax she had spun from the nettles were lying on the floor, and

hanging up by the ceiling was the shirt she had finished. One of

the hunters had brought all this along as a curiosity.

“You can dream about your former home here,” said

the king. “Here’s the work that you used to do. It’ll amuse you to

think back to that time now that you’re surrounded with

luxury.”

When Elisa saw these things that were so close to

her heart, a smile came to her lips, and the blood returned to her

cheeks. She thought about her brothers’ salvation and kissed the

king’s hand. In return he pulled her to his heart and had all the

church bells proclaim the wedding feast. The beautiful silent girl

from the forest was to be queen of the land.

The arch-bishop whispered evil words into the

king’s ear, but they did not reach his heart. The wedding was set,

and the arch-bishop himself had to place the crown on her head.

Although he pressed the narrow band down on her forehead with evil

resentment so that it hurt, there was a heavier band pressing on

her heart—the sorrow she felt about her brothers, and she did not

feel the bodily pain. Since a single word would kill her brothers,

her mouth was silent, but in her eyes lay a deep love for the good,

handsome king, who did everything he could to please her. Day by

day she grew to love him more and more. Oh, if only she dared to

confide in him, to tell him of her suffering! But she had to remain

silent, and in silence she had to finish her work. Night after

night she stole away from his side and went into her little closet

that resembled the cave. She knit one thick shirt after the other,

but when she started on the seventh one, she ran out of flax.

She knew that the nettles that she should use grew

in the churchyard, but she had to pick them herself. How was she

going to get there?

“Oh, what is the pain in my fingers compared to the

agony in my heart!” she thought. “I must risk it. God won’t desert

me!” With terror in her heart, as if she were on her way to do an

evil deed, she stole down to the garden in the moonlit night. She

went through the long avenues of trees and out on the empty

streets, to the churchyard. On one of the widest tombstones she saw

a ring of vampires—hideous witches, who took off their rags as if

they were going to bathe and then dug down into the fresh graves

with their long, thin fingers, pulled the corpses out, and ate

their flesh. Elisa had to pass right by them, and they cast their

evil eyes on her; but she said her prayers, gathered the burning

nettles, and carried them home to the castle.

Only a single person saw her—the arch-bishop. He

was awake when others slept. Now he felt vindicated, for the queen

was not what she seemed. She was a witch, who had bewitched the

king and all the people.

In the confessional he told the king what he had

seen, and what he feared, and when the harsh words came from his

tongue, the images of the carved saints shook their heads as if

they wanted to say, “It isn’t so. Elisa is innocent!” But the

arch-bishop explained it differently. He said they were witnessing

against her and shaking their heads over her sin. Two heavy tears

rolled down the king’s cheeks, and he went home with doubt in his

heart. He pretended to sleep that night, but remained wide awake.

He noticed how Elisa got up, and how she repeated this every night,

and every night he followed her quietly and saw her disappear into

her little chamber.

Day by day his face grew more troubled. Elisa saw

this and didn’t know why, but it worried her, and she was still

suffering in her heart for her brothers. Her salty tears streamed

down and fell upon her royal velvet and purple clothing. They lay

there like glimmering diamonds, and everyone who saw the rich

magnificence wished to be the queen. In the meantime she had

finished her work. Only one shirt was left, but she was again out

of flax and didn’t have a single nettle. One last time she would

have to go to the churchyard and pick a few handfuls. She thought

about the lonely trip and about the terrible vampires with dread,

but her will was firm, as was her faith in God.

Elisa went, but the king and arch-bishop followed

her. They saw her disappear at the wrought iron gate of the

cemetery, and when they came closer to the gravestones, they saw

the vampires, as Elisa had seen them. The king turned away because

he thought she was among them—his wife whose head had rested

against his breast this very night!

“The people must judge her,” he said, and the

people judged that she should be burned in the red flames.

From the splendid royal chambers she was led into a

dark, damp hole, where the wind whistled through the barred

windows. Instead of velvet and silk they gave her the bundle of

nettles she had gathered; she could rest her head on those. The

hard, burning shirts she had knit were to be her bedding, but they

couldn’t have given her anything dearer to her. She started her

work again and prayed to God while outside the street urchins sang

mocking ditties about her, and not a soul consoled her with a

friendly word.

Toward evening a swan wing whistled right by the

window grate. It was the youngest brother who had found his sister,

and she sobbed aloud in joy, even though she knew that the

approaching night could be the last she would live. But now the

work was almost done, and her brothers were here.

The arch-bishop came to spend the last hours with

her, as he had promised the king he would do, but she shook her

head and asked him to leave with expressions and gestures. She had

to finish her work this night, or everything would be to no

avail—everything: pain, tears and the sleepless nights. The

arch-bishop went away with harsh words for her, but poor Elisa knew

that she was innocent and continued her work.

Little mice ran around on the floor, and pulled the

nettles over to her feet, to help a little. By the barred window

the thrush sat and sang all night long, as merrily as he could, so

she wouldn’t lose her courage.

It was an hour before dawn when the eleven brothers

stood by the gate to the castle and asked to see the king, but they

were told that they couldn’t because it was still night. The king

was sleeping, and they didn’t dare wake him. They begged, and they

threatened. The guards came, and even the king himself appeared and

asked what this meant. At that moment the sun came up, and there

were no brothers to be seen, but over the castle flew eleven wild

swans.

All the people in the town streamed out of the

gates. They wanted to see the witch burn. A miserable horse pulled

the cart she was sitting in. They had given her a smock of coarse

sackcloth, and her lovely long hair hung loosely around her

beautiful head. Her cheeks were deathly pale, and her lips moved

slowly while her fingers twined the green flax. Even on her way to

her death she did not stop the work she had started. Ten shirts lay

by her feet, and she was knitting the eleventh. The mob insulted

her.

“Look at the witch! See how she’s mumbling. And she

doesn’t have her hymnal in her hands! She is sitting with her magic

things. Let’s tear them into a thousand pieces!”

And the crowd approached her and wanted to tear her

things apart, but then eleven white swans flew down and sat around

her on the cart and flapped with their huge wings. The mob fell

back terrified.

“It’s a sign from heaven! She must be innocent!”

many whispered, but they didn’t dare say it aloud.

As the executioner grabbed her hand, she hastily

threw the eleven shirts over the swans. There stood eleven handsome

princes, but the youngest one had a swan’s wing instead of one arm,

since there was a sleeve missing in the shirt. She hadn’t been able

to finish it.

“Now I dare speak!” she said, “I am

innocent!”

And the people who saw what had happened bowed down

before her as if for a saint, but she sank lifeless into the arms

of her brothers. The tension, terror, and pain had affected her

this way.

“Yes, she’s innocent!” said the eldest brother, and

he told them everything that had happened. While he was speaking,

the people could smell the scent as of a million roses because all

of the logs in the bonfire had sprouted roots and branches. There

was a fragrant hedge standing there, big and tall with red roses.

At the top was a flower, white and shining that lit up like a star.

The king picked it and set it on Elisa’s breast, and she awoke with

peace and happiness in her heart.

Then all the church bells rang by themselves, birds

came flying in big flocks, and the bridal procession that led back

to the castle was like no other seen before by any king.

NOTE

1. A mirage (an optical phenomenon, often

characterized by distortion) that appears near an object, often at

sea; named after the sorceress Morgan le Fay, sister to King

Arthur, who was said to be able to change her shape.