4 form

“Art is nothing without form.”

GUSTAVE FLAUBERT (FRENCH, 1821–1880) Novelist, Playwright

form \'f rm\ n

rm\ n

1 a: the shape and structure of something as distinguished from its material, or the shape and structure of an object

Basic forms are derived from basic shapes—a square becomes a cube, a circle becomes a sphere, a triangle becomes a pyramid. The terms shape and form are often confused with one another as if they meant the same thing. In chapter 3, criteria and characteristics that define shape were explained. Form is achieved by integrating depth or volume to the equation of shape. It is a three-dimensional element of design that encloses volume. It has height, width, and depth. For example, a two-dimensional triangle is defined as a shape; however, a three-dimensional pyramid is defined as a form. Cubes, spheres, ellipses, pyramids, cones, and cylinders are all examples of geometric forms.

Form is always composed of multiple surfaces and edges. It is a volume or empty space created by other fundamental design elements—points, lines, and shapes.

The CNN Grill was a “wired hub of political activity” for journalists, operatives, and celebrities during national political conventions. Bold, illuminated geometric forms and typography, coupled with patriotic colors, created a strong and memorable identity for this temporary gathering venue.

COLLINS

New York, NY, USA

The paper slit of this cover for Camera Work magazine creates a three-dimensional, concave surface on a two-dimensional plane that is further strengthened by the asymmetrical placement of typography on the cover.

MENDE DESIGN

San Francisco, CA, USA

The pop art, cartoonlike visual character of this dialog box creates a dynamic and playful three-dimensional form for the containment of “Pop Justice,” a logotype for one of England’s popular blogs. Vibrant, analogous colors and bold letterforms, sans their counters, further create visual impact without overpowering the logotype’s spatial depth and volume.

FORM

London, UK

1983

Aluminum Alphabet Series

TAKENOBU IGARASHI

Tokyo, JP

Takenobu Igarashi and the Aluminum Alphabet Series

TAKENOBU IGARASHI (b. 1944), a Japanese sculptor and designer, has continually explored the fusion of two-dimensional and three-dimensional form. His work is based on a language of basic elements—point, the purest element of design; line, which delineates locations and boundaries between planes; shape, realized flat or dimensional; texture, visual or tactile; and grid, whose horizontal and vertical axes provide order and logic to a composition.

Although the majority of his work for the last thirty years has been in graphic identity, environmental graphics, and product design, his exploration and experimentation with letterform and isometric grids has brought him international attention and recognition. In the early 1980s, his two-dimensional, isometric alphabets, first conceived as a series of poster calendars for the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, quickly evolved into three-dimensional alphabetic structures that Igarashi called architectural alphabets.

The Aluminum Alphabet Series, the first to involve typographic sculptures, comprises twenty-six three-dimensional, aluminum letterforms. Each sculptural form consists of a series of aluminum plates of varying thickness joined together by flat-head aluminum fasteners. Here, Igarashi uses letterform to explore the potential of three-dimensional form. He says, “One of the charms of the Roman letter is its simple form. The wonderful thing is that it is created with the minimum number of elements; the standard structure is based on the circle, square, and triangle, which are the fundamentals of formation.”

Letterforms are basically symbols or signs written on paper in a flat, two-dimensional world. Design of letterforms can be varied by extending their two-dimensional characteristics into a three-dimensional world. Letterforms can also be considered as simple graphic compositions of basic geometric elements—circles, squares, and triangles. Within these compositions are hidden possibilities for developing a greater set of shapes and forms.

Igarashi’s approach for this series was to conceive letterforms as solid volumes divided into positive and negative spaces. A three-dimensional composition is realized when the form of the letter is extended in both its positive and negative directions; in other words, by generating spatial tensions in both directions. He states, “This is one example of my attempt to find a geometric solution between meaning and aesthetic form. Based on a 5-millimeter [1/4 inch] three-dimensional grid system, the twenty-six letters of the alphabet from A to Z were created by adding and subtracting on the x-, y-, and z-axes.”

The Aluminum Alphabet Series is a unique, groundbreaking result of taking a conceptual, spatial, and mathematical view of letterforms and revealing some of the many possibilities of shape and form. It is the ultimate study in letterform, material, detailing, visual interpretation, and three-dimensional form.

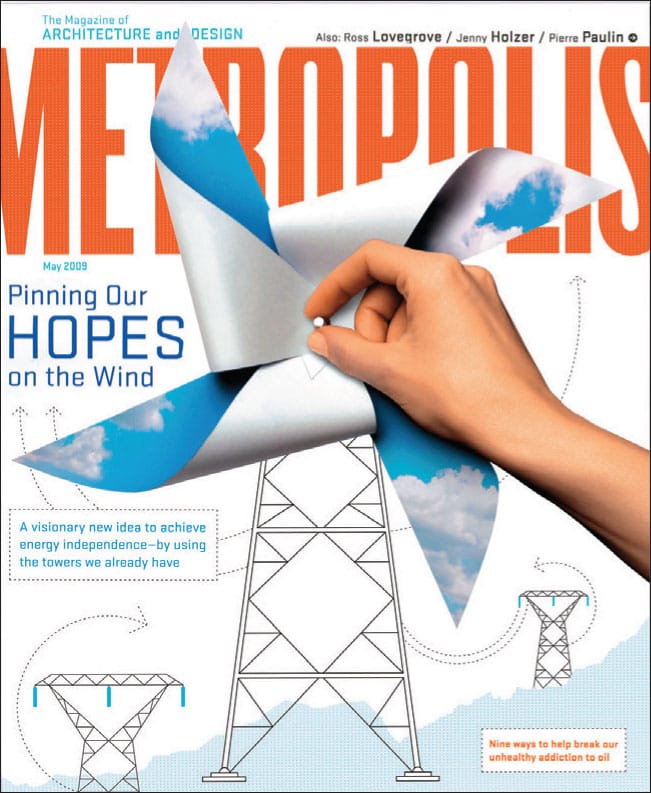

In this cover for Metropolis magazine, the juxtaposition of three-dimensional forms—a pinwheel and a person’s hand—on a two-dimensional representation of the same form creates a visually dynamic, engaging, and memorable cover.

COLLINS

New York, NY, USA

Types of Forms

Forms can be real or illusory. Real, three-dimensional form contains actual volume or physical weight while illusory, two-dimensional form is perceptual. Real forms are three-dimensional such as objects, sculpture, architecture, and packaging. Illusory forms are illusions of three-dimensional shapes in two-dimensional spaces and can be realized three-dimensionally by using several graphic conventions to achieve illusory results.

Projections

Representing several surfaces or planes of a two-dimensional form all at once is one way to visually represent a three-dimensional form without it receding in space or in scale. The most common types of projections are as follows:

Isometric

An isometric projection is the easiest of projection methods where three visible surfaces of a form have equal emphasis. All axes are simultaneously rotated away from the picture plane and kept at the same angle of projection (30 degrees from the picture plane), all lines are equally foreshortened, and the angles between lines are always 120 degrees.

These three marks represent the breadth and spirit of the Smithsonian's Cooper-Hewitt National Design Week, an annual education initiative. Their design implies a three-dimensional volume or environment that contains iconic forms of furniture, lighting, and related functional objects. The figure-ground relationships evident in each of these marks reinforce a visual interplay between two-dimensional and three-dimensional forms.

WINK

Minneapolis, MN, USA

Types of Projections

Types of Perspective

This assignment explores the visual relationships between typographic form and architectural form. This student based her photographic exploration and analysis on the angles and geometry found in Daniel Liebskind's Denver Art Museum building and in the typeface, Futura (Paul Renner, 1927).

CASSANDRA BARBOE, Student

HENRIETTA CONDAK, Instructor

SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS

New York, NY, USA

Axonometric (or Plan Oblique)

An axonometric, or plan oblique, projection is a parallel projection of a form, viewed from a skewed direction, to reveal more than one of its sides in the same picture plane.

In isometric and axonometric projections, all vertical lines remain vertical and all parallel lines remain parallel.

Spatial Depth

Three-dimensional space and depth can also be achieved when one surface of a form is overlapped and partially obscured by another form. One- and two-point perspective drawings exemplify creation of a form’s spatial depth with two-dimensional shapes overlapping on a two-dimensional picture plane.

(See diagrams shown here)

Tone and Shading

Form can also be visually indicated through tone, shade, and texture. The surfaces of a form curving or facing away from a directed light source appear darker than surfaces facing a directed light source. This effect suggests the rounding of a two-dimensional shape into a three-dimensional form.

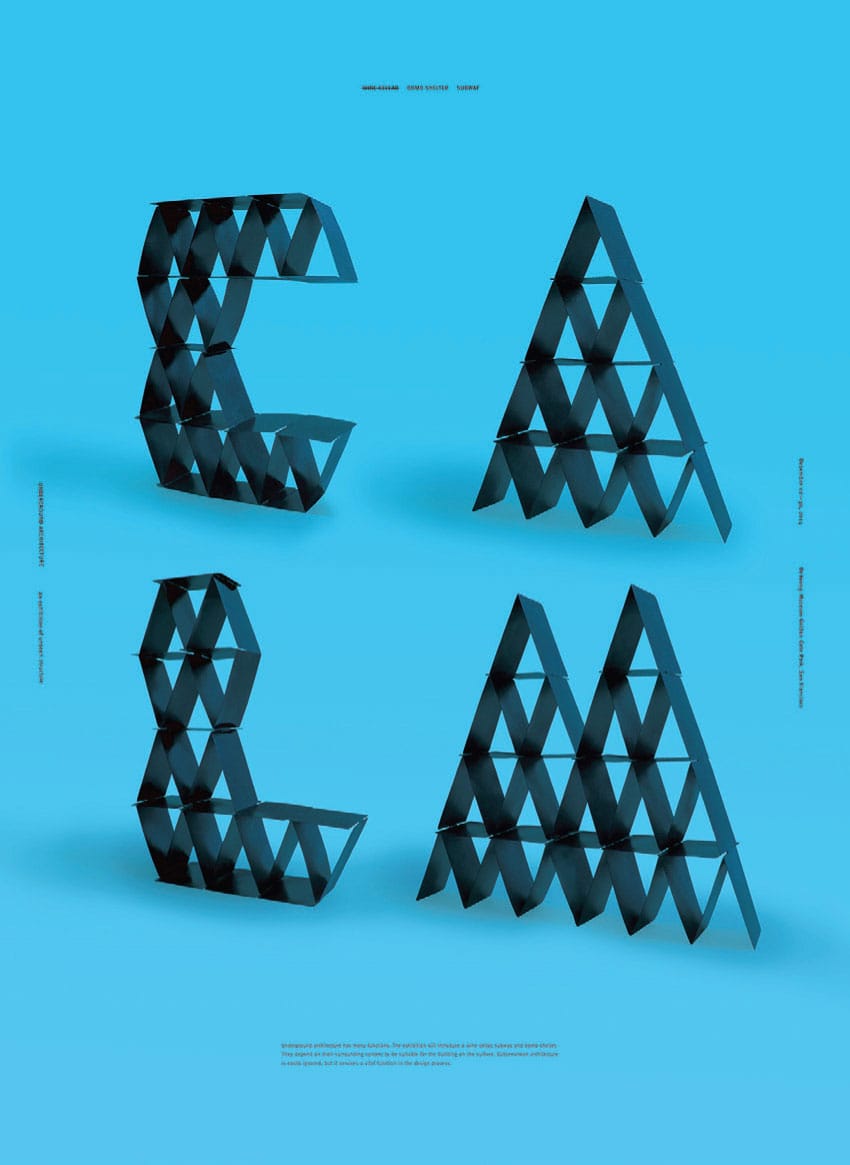

This poster for a hypothetical architectural exhibition explores underground architectural spaces such as a bomb shelter, paired with the word "calm." This theme is further emphasized with the use of large-scale three-dimensional letterforms that provide depth, volume, and shadow, strengthening these unique forms and the identity of the poster.

YU RONG, Student

KATHRIN BLATTER, Instructor

ACADEMY OF ART UNIVERSITY

San Francisco, CA, USA

The primary visual element of this promotional poster celebrating the anniversary of Casa da Musica, Portugal’s world-renowned concert hall, relies upon its unique and unconventional symbol—a stylized, trapezoidal form derived from the building’s architecture. It is fragmented by facet and color, further implying a three-dimensional appearance and communicating the diversity of music performances scheduled for the anniversary season.

SAGMEISTER & WALSH

New York, NY, USA

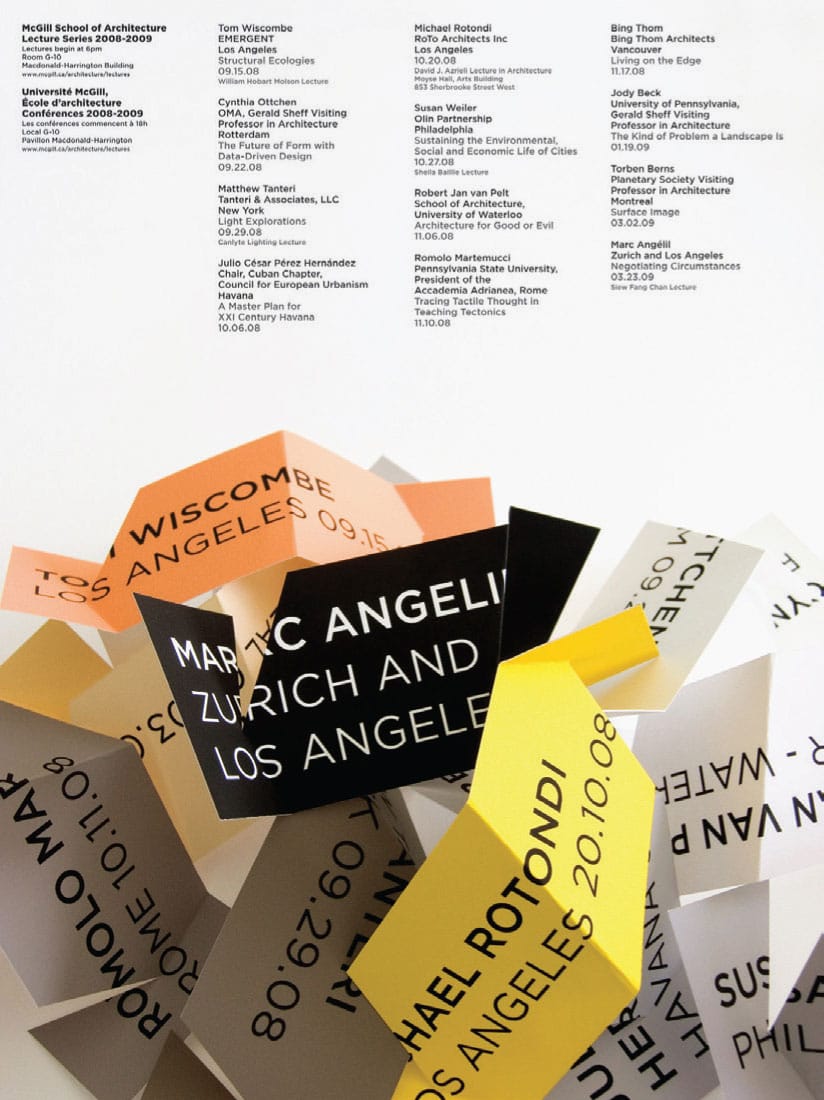

This promotional poster series for the McGill School of Architecture uses form as a primary vehicle for communicating an emblematic element in architecture. Each lecturer’s name is printed on a colored strip of paper and folded to evoke an architectural form. These paper strips were photographed together to announce the series, and individually to announce each lecture. Each photographic composition is unique, adding a strong visual dynamic to the poster series. An organizational grid for narrative, informational text is used consistently on all posters and is a contrasting juxtaposition to each free-form, three-dimensional photographic composition.

ATELIER PASTILLE ROSE

Montreal, QUE, CA