James Fenton & Darryl Pinckney

The paint has been removed from the carved mahogany of the dining room, but the missing coving on the plaster ceiling has yet to be replaced. This is the first of four oval rooms, where even the windows and the doors are curved.

You could devote a whole book to James Fenton and Darryl Pinckney’s house, in Mount Morris Park in Harlem, an amazing fantasy palace which you mightn’t be surprised to find in Dickensian London but don’t expect to come across on the upper reaches of Manhattan.

Once through the impressive and imposing pillared portico with its carved lintels and arch, through a bluebeard-looking front door (“the letter box was a hole cut into the mahogany”), you’re in the first reception hall, aka down the rabbit hole in a house that is 25 feet wide and 10,000 square feet. “It is big,” James allows, “and I love it. When I first saw the front entrance I thought it might be by McKim, Mead & White, as it’s very much in that style, but the architect was Frank Hill Smith, a Bostonian artist, architect and interior designer who obviously paid great attention to what Stanford White and his colleagues were up to, as this entrance is a version of what they had done a year before, at the Judson Church on Washington Square.”

Once through the door you’re in a cosmos full of remarkable color, entrancing objects, and enticing spaces which include oval rooms, snaking staircases, inviting landings (rooms in themselves), which in turn reveal stained-glass windows, panelled walls, color heaped on vibrato color, textures of many colors and provenances, textiles from all over the world – heaped velvets and hanging linens – intriguing paintings, elaborate plasterwork and collected treasures, archaeological finds, German Expressionist prints, daguerreotypes, American furniture (Emeco Navy chairs), English furniture, rarities, and various relics, terracotta tiles, sculpture – all contained without pretension or studied arrangement in the felicitous whole.

They bought it when they moved from England seven years ago. “If we were going to move to New York then Darryl wanted to live in Harlem. I was in England, in not the most creative period of my life, when I saw this boarded-up house on the StreetEasy website. I phoned Darryl and said, ‘Go look.’”

What followed was an epic adventure into the wilder shores of house purchase. They had form on rescuing melancholy buildings, having rescued a decaying house near Oxford years before – it became a model of stunning interiors and great gardens. But they had no idea of the nightmare in store for them here.

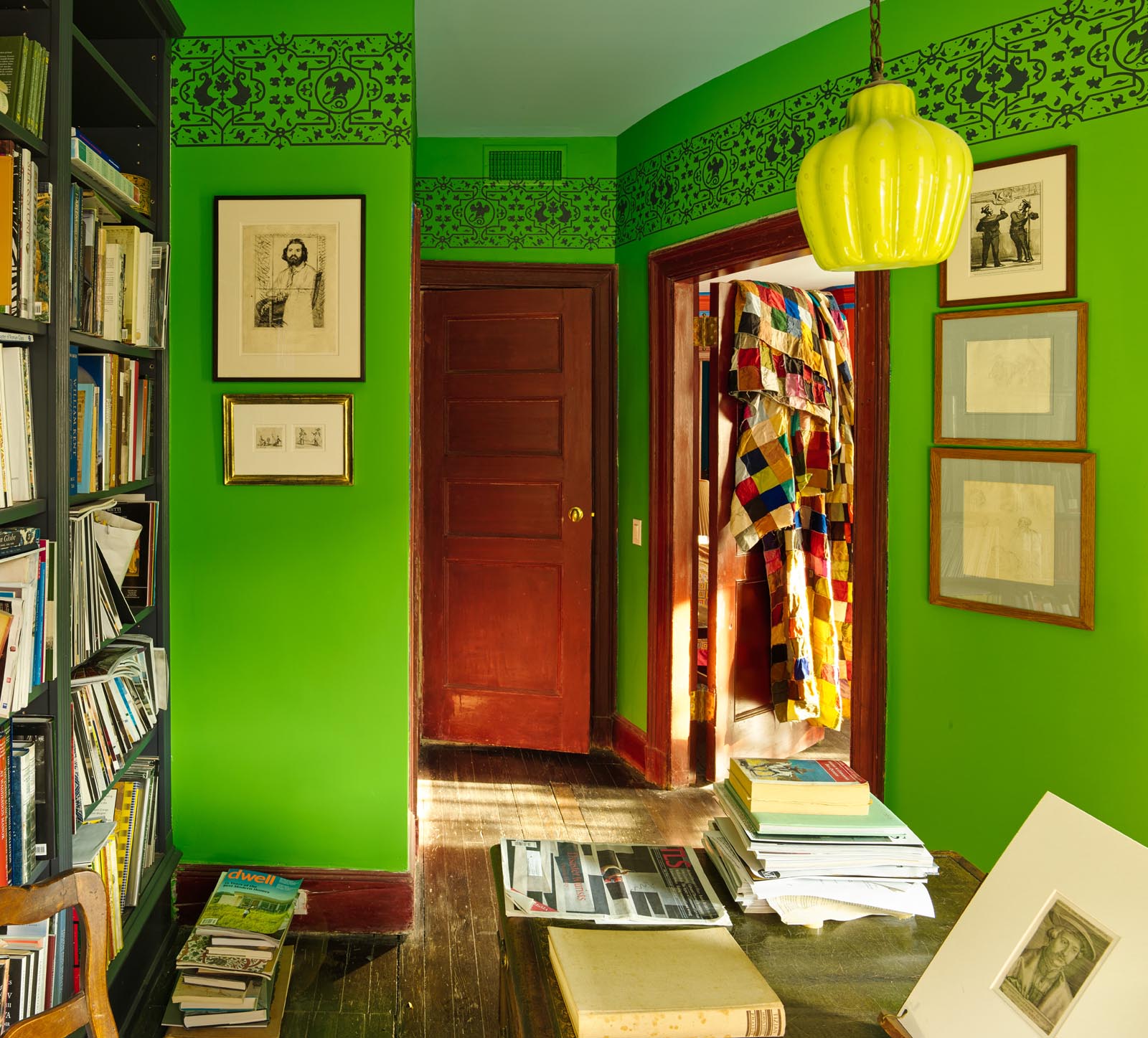

The library occupies an extension added in the 1920s. The metal shelving is a classic Dieter Rams design, manufactured by Vitsœ. The print is by Howard Hodgkin.

A glimpse of a green bathroom, off a landing painted in Pacific Ocean Blue (by Benjamin Moore, like nearly all the paints used). Much of the original main staircase had been removed, but here you can see the rich oak panelling and the balusters with their alternating barley-sugar twist. The chest on the landing is made of Italian intarsia work fragments. The bronze head is by Peggy Garland. The painting is Genoese and the marble relief is Paduan.

They are neither of them what you might call entrepreneurs. James Fenton is a major poet of emotional depth and lyric beauty (although his poems occasionally have a refreshing sting of venom), who has lived a wide-ranging life. He has farmed in the Philippines and was a war correspondent in Vietnam, riding the first North Vietnamese tank into the presidential palace when Saigon fell in 1975. He is an acclaimed playwright and has been a political journalist and a drama critic, loves opera, the theater, is a regular book reviewer and columnist (a salient point is that he once wrote a libretto for Les Misérables which, although not produced in his version, gave him a share in the proceeds from the subsequent musical). He is also a discerning collector. Darryl Pinckney is an erudite American novelist, dramatist, reviewer and columnist with many awards to his name. He is also a long-time collaborator with the experimental theater director Robert Wilson, and he wrote the scenario for the ballet-drama Letter to a Man, with Mikhail Baryshnikov as Nijinsky.

One of James’s poems is called “A Vacant Possession” – and the house that Darryl and he uncovered and that is now in their possession was more than vacant: it was screamingly empty, desolate, fought over and beleaguered.

It had been a place of worship for the snappily named Commandment Keepers Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation of the Living God Pillar & Ground of Truth, Inc., who believe that people of Ethiopian descent represent one of the lost tribes of Israel and claim King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba as their ancestors. Anyway. When the synagogue went on the market a protracted and bitter battle developed between various warring factions of the sect. This was finally resolved in a court judgment, but even then the new owners had to endure barracking, windows being broken and protesters vandalizing the building. “It made life unpleasant,” James says. But they faced it down and never lost their passion for the derelict old beauty.

“A year after we had bought it we got our ducks in a row and were able to start work – but every time we arrived the door would be padlocked or we’d find crazy glue on the door. I remember when the removal men first came to deliver stuff we had to guarantee they had come to the right address – they simply could not countenance that anyone lived here.”

When they moved in they had three usable rooms – a study each and a bedroom – but no shower and only a makeshift sink. “We showered at the gym and ate out for at least a year . . . we had to upgrade the gas supply, the electrical system, everything. At one time some small-time thief took all the lead from the house. And then we found a gushing great geyser in the basement.”

The kitchen stove occupies the space where the original stood, and is surrounded by the original tilework, found under a layer of plaster. The red chairs are Emeco’s classic “Navy” chair. To the right of the cooker hangs a Tom Phillips print based on an old postcard. The poster by the window is from an Edinburgh exhibition of daguerreotypes and the photos are mostly by friends. The shelves, from the former Archivia bookshop on Lexington, hold cookbooks.

You have to see this house to believe how immense is the work they have undertaken. Even imagining it makes one want to go and lie down in a darkened room; the fire escapes snaking up the exterior have to be dismantled, and the original delicate ironwork over the oriel-like grids on the windows, the endless railings around the house, all are being scraped down by hand in Sisyphean labor.

When Darryl first went to reconnoiter the building it was in complete darkness and he had to explore the huge interior by the light of a torch, but he telephoned James in astonishment to relay what he was seeing, room by room . . . “and some of them are oval!” The idea of oval rooms fascinated them both – and indeed they are beautiful rooms, with their mahogany doors following the curve of the walls. (They later discovered in part of their deep research that the architect, Frank Hill Smith, had previously – in the mid-1880s – built a fine house with oval rooms in Boston.)

Everywhere was neglect and depredation, with the rooms’ fine proportions disguised. The second floor had been divided up into many small rooms, and the ghostly shadows of their partitions are still visible – but the plasterwork and fireplaces had not been damaged. The same with the kitchen, where three rented rooms had been squashed into the space and where they found, hidden behind plaster, the original tiles around the cooker.

The house was built in 1890 by John Dwight, a co-founder of Arm & Hammer, a household name still for products such as baking soda and toothpaste (the monogrammed initials JD remain impressed in the plaster on the dining room). Soon after James and Darryl bought it they were delighted to find that the Dwight family still had photographs of the building taken in the 1920s, before they sold it – plus, best of all, the plans and blueprints. Every room save the cellar and bathrooms had been documented. “We were thrilled. We invited them to lunch in their old dining room – we made a camp kitchen, had a cook and a waiter and a three-course meal in the empty building and they didn’t bat an eyelid.”

Their contractor, Miles Casey, called the Dwight trove “the Rosetta Stone,” and architect Sam White, great-grandson of Stanford White, was riveted by the precise documentation. “Before we had the photos, he had made a guess at what the entrance hall would have looked like (based on the earlier house in Boston) but then we found it was a different version of the same idea. Sam played a major role in the early stages, getting the basic things seen to – mostly technical like the redesign of the drainage and the water and so forth.” Although they used the invaluable documentation they did not build a simulacrum – as James says, “We are not aiming to take it back to the 1890s but to act freely within the general idiom of the original structure.” As a result nearly all the magnificent rooms and landings, so badly treated over the years, have been restored to their previous dignity and first shape and function.

A small study, painted in glowing Fresh Scent Green. The drawings and prints are by Daumier and others. The filigree stencilled frieze was designed and executed by artist Jane Warrick. The ceilings are painted in the very pale blue Morning Glory, the default color throughout the upper floor.

This one of the three oval bedrooms is painted in Smoldering Red, with Paddington Blue for a contrasting trim (imitating the blue of standard painters’ masking tape). The matching bedspread is by Missoni. By the window is a plaster bust of an African man, inscribed Kongo. Framed Persian carpet fragments hang on the wall.

The detailed carving on the mahogany woodwork, concealed under thick layers of paint, was painstakingly stripped back to crisp detail. The fireplaces, with their elaborate overmantels and surrounds, including Mexican onyx, are in working order, and the kitchen now looks much as it did decades ago. The fine floors, hidden under dingy wall-to-wall carpeting, have been sanded down and strewn with handsome old rugs and carpets that were “mostly cheaply bought at auctions.” The panelling, frowsty under its heavy coats of paint, was also stripped down – a time-consuming project – and plaster casts have been made to restore woodcarvings, friezes and pilasters.

When it came to the decoration of the rooms, that was all James’s work. Every corner of this massive house speaks of its owners’ sensibilities and courage, not to say poetic stoutheartedness.

They aren’t only restoring the house. Their lives teem with books, so as well as the library built in 1920 they have added a new one in what used to be a servants’ room, using the German classic shelving system designed by Dieter Rams and manufactured by Vitsœ since the 1960s. Other fine bookshelves came from Archivia, a favorite bookshop on Lexington Avenue. “Then one I day I walked past and the shutters were up. I rattled on them and the owner came to the door. She was closing it down. “You can’t run a bookshop on the Upper East Side any more.” I asked what was going to happen to the shelves and it seemed they were probably going to the dumpster.”

Well, here they are now in their alluring new-old library and very fine they are.

And every room resonates with particular glorious color. A central upstairs landing – a room in itself, with its dark blue ceiling and mahogany beams – has trompe l’œil porphyria walls and blue stencilled friezes over Dutch Gold, by the artist Jane Warrick. There are two grand pianos in the stunning yellow drawing room, and the back staircase is a shade of indigo that is like a desert sky at night. Every room has its lacings of rare and distinctive objects, the fruits of James’s many years as a collector, in an uncommon mixture of exuberance and gravitas, of enjoyment and dignity. “Where do you get all these treasures?” I exclaim; and he admits “I look at catalogues a lot of the time.”

On one landing are chairs by Robert Gillow, an English furniture-maker who started out as a carpenter on a ship bound for the West Indies in 1720. There he became interested in mahogany and brought samples of the wood back (the first mahogany to be imported to England) and in 1730 he founded a firm, Gillow of Lancaster, which supplied quality furniture and furnishings to the English gentry. James has had them covered in a Bhutanese fabric he found in Robert Kime’s enticing shop in London.

The undertaking of the rebuilding of this historically important mansion has become a much bigger and more expensive endeavor than they envisaged – almost a chivalric venture. The work continues year by year and as they research and restore they discover new things all the time about American furniture and interiors.

They have created something which reflects the original grandeur of the house but which is also of their own time, and reflects their sensibility and their poetic and artistic occupations. They both know that without their rescue this stately grande dame of a house would have been gutted or even demolished. And they get great satisfaction from seeing the house come alive and breathe again. And they love living there.

The yellow drawing room, with its elaborate plaster ceiling painted in White Sand, is restored to its former glory. The fireplace with its onyx surround is original; a small group of Renaissance bronzes and baroque terracotta figures finds its home here, below a fine Regency mirror. The rug is Indian. The architect, Sam White, gave the chandelier as a present to the house.

The stencilled frieze in blue and Dutch Gold by Jane Warrick pays homage to the long-gone original Lincrusta frieze in green and gold.

The restored former servants’ staircase has the woodwork painted in Day’s End, and the walls in Pacific Ocean Blue.