Kenneth Jay Lane

In the sumptuous salon, orientalist paintings glow against the chocolatey Herculon-covered walls. French windows shaded by ruched tambour blinds overlook Park Avenue.

I’m in his apartment and it’s glamorous. So is he. Beau Brummel. Witty. Irreverent. Handsome. Sly. And funny. A dandy. And sharp. Horribly so. Don’t get off your guard. He still is all these things, though he is well into his eighties. And his apartment matches his character. He has a fine sardonic edge to his conversation and pretends not to take things seriously, but he didn’t get to the top of his richly accoutred haute-boho tree through frivolity.

I first met him in the 1960s, when I was working at Vogue and he was in vogue, already one of the most iconic jewellery designers in the world. His fabulous ornaments channelled Schlumberger, Jeanne Toussaint, Fulco di Verdura, Bulgari, Cartier and Chanel − snakes and shells and puppy dogs’ tails and whatever that singular eye of his happened upon was given its own rococo glittering spin. Every fashionable woman wanted this new fabulous “junque” jewellery.

He was once known as the King of Faux (even his book, an autobiography of his designs, is called Faking It), but now his jewellery is its own covetable thing. The Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum holds examples and some of his vintage pieces are collectors’ items. He still works and loves it and sells any quantity of his new designs on television shopping channels to a new generation, all over the world. “I like to create jewellery that can be worn any time of the year, by any woman.”

(Historical note − his jewellery has been worn by every First Lady since time began; Barbara Bush wore his three-strand pearl choker to her husband’s Presidential Inaugural Ball and there’s a famous photograph of Jacqueline Kennedy practically being strung up by John, her baby son, as he plays with her KJL triple-strand pearl necklace that she bought for less than two hundred dollars. It was sold at auction, after her death, for over two hundred thousand.)

He coins aphorisms at the drop of a cabochon. “Style and chic are not the same things. Chic is sort of being au courant. Style is not.” “It’s not what the woman has on her back, it’s to do with her mind.” ’Imagination is everything.”

There is an element of the fabulous about both him and his grande luxe duplex in one of the handful of surviving mansions on Park Avenue, in the Murray neighborhood, built in the Italian Renaissance revival style by Stanford White of McKim, Mead & White. When it was finished in 1892 one of the founders of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, architectural critic Russell Sturgis, pronounced it “the most dignified structure in all the quarter of town, not a palace, but a fit dwelling house for a first-rate citizen.” So Kenny, as his friends call him, has come home.

In the 1920s it was converted into the Advertising Club and in 1977 it was developed into apartments. Kenneth Jay, who lived in a swish little place nearby, watched progress with deep interest and an eagle eye, and before there was even a prospectus he gained access and wrote out a check for the only apartment with a balcony.

Two 17th-century marble busts of a male and a female warrior – regularly loaned to the Metropolitan Museum of Art – stand on the mantelpiece of the original Italian marble fireplace. The ceiling with its fine plasterwork is also original to the house; hanging from it are signature lamps from the venerable firm of Denning & Fourcade.

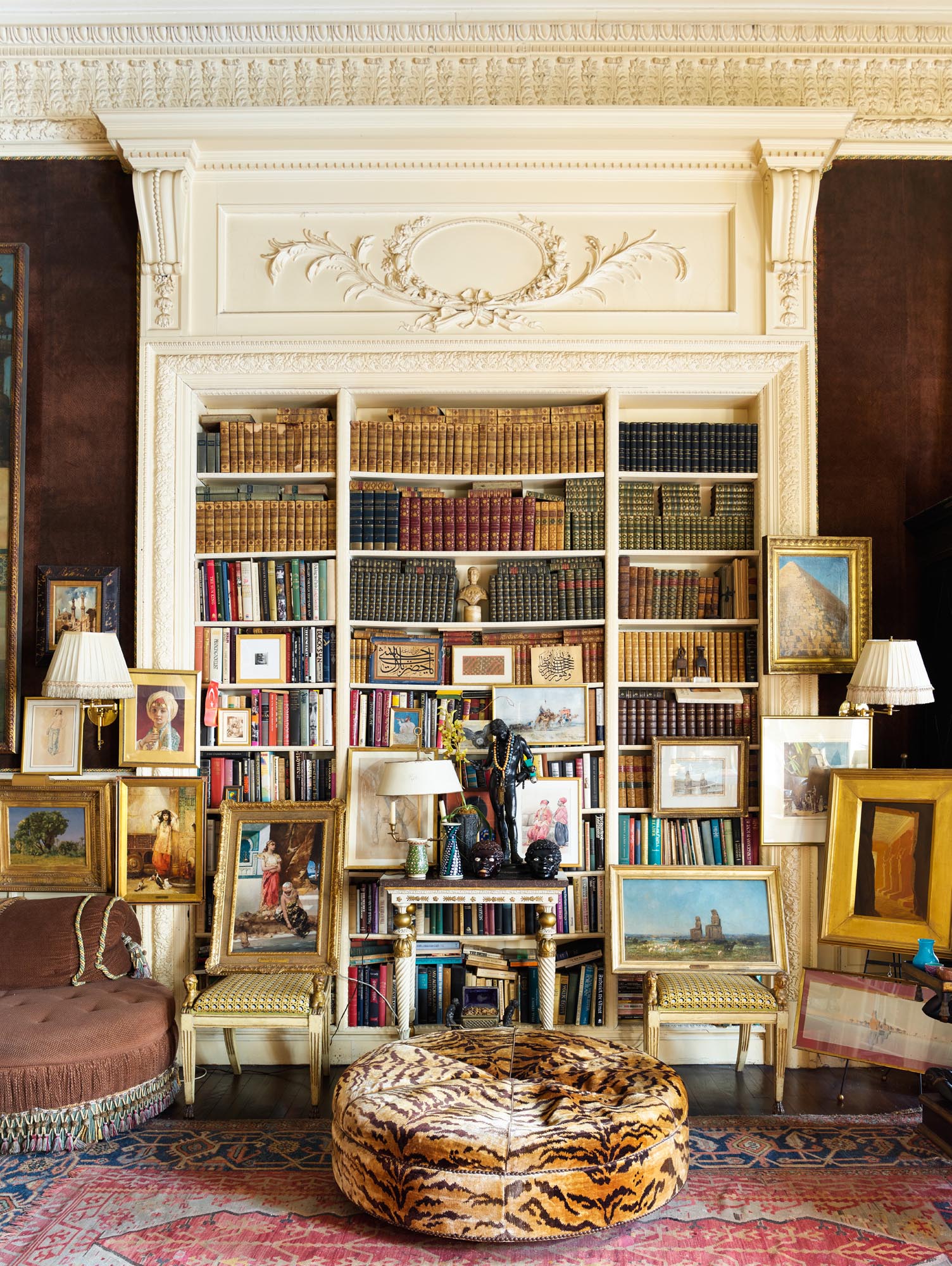

Another seating area in front of a large bookcase with a carved pediment, one of a pair bought as double doors at auction. The pouffe is covered with tiger-skin fabric from Le Manach.

By the windows are a Louis XIV Boulle Mazarin desk, a pair of Louis XVI chairs covered in handwoven Indian fabric and an ormolu and alabastro fiorito gueridon with a pierced palmette cast edging.

The balcony overlooks Park Avenue. “I love to stand there,” he once said. “If I turn one way I can look all the way uptown. The other way and it’s almost down to Union Square. If there’s a snowstorm it’s like being inside one of those glass paperweights which you shake so the snow falls.” He was also seduced by the rare proportions of the place. “I think it’s impossible to live in a room that isn’t at least 13 feet high, he once said – without a blush – and here he found 16-foot-high ceilings and a chance to make another jewel of his own devising. He gutted most of what was there, keeping the vast original hand-carved Italian marble fireplace, but removing a marble staircase in the middle of what is now his distinctly opulent salon. He designed the interiors himself and his own master carpenter made the stairs and woodwork.

I love John Richardson’s immortal words about the enormously rich eccentric bon vivant and nasty aesthete Charles de Beistegui: “A decorator of genius, Beistegui was fortunate in having a client of genius. Himself.” Kenneth Lane is fortunate in being his own genius client – a master of rare objects and elusive space.

Once inside the double trompe l’œil walnut doors of his domain you’re in the hall and dining room muffled with voluptuousness, a cantilevered staircase (which he designed himself) leading up past the scarlet red walls with their perfectly placed sconces up, up, up to a mezzanine balcony wherein is his library (and some enormous paintings and Chinese pots and garden stools) and thence to the hidden glories of his bedroom, patterned after the Paris apartment of Marie-Blanche de Polignac, the daughter of couturier Jeanne Lanvin. The mahogany and faux ebony surround of the overmantel and fireplace is copied from the Empire-inspired doors of her library, designed by architect Emilio Terry, and there are some wonderful paintings, including one of The Sleep of Endymion by Anne-Louis Girodet.

The main room, a 27-square-foot salon, wonderfully high, of course, with an elaborate molded plaster ceiling and a huge Heriz carpet, is a rich dialogue of color, harmony and contrast, visually and proportionally perfect, and inspires a sense of calm that is light years away from the tumult of Grand Central Station nearby.

The walls are hung with his collection of orientalist pictures, many by John Frederick Lewis, Jean-Léon Gérôme and Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, and the mixture of textures and patterns, of different seating from sofas to ottomans to grand chairs (with a lot of faux leopard around), the elaborate ruffled curtains, the pictures and the polish give it the air of an American translation of English country house style – a little Edwardian – or grand Proustian French, with that twist of baroque fluency that is all his own. Urbane connoisseurship on show.

Tall faux palms flourish by the French windows, and the walls are close-hung with European as well as Pharaonic paintings (close-hanging is a skill that he has at his fingertips). The wall covering is chocolate-brown Herculon, a synthetic fiber mostly used for car upholstery but which under his alchemy looks deeply luxurious. The lighting of any great room is a giveaway of taste. He didn’t want chandeliers so it’s lit by huge arm lamps with fringed silk shades, the signature lamps of Robert Denning of Denning & Fourcade, a now defunct New York interior design firm known for extravagance and over-the-top opulence. They look clubby and terrific.

On every surface, including a Louis XIV Boulle Mazarin desk, and tables topped with pietra dura, pretty lamps and objects from all over are mixed and matched with insouciance. He places fanciful objects with amusement value (“silly things” he says, complacently, poking fun at himself – he’s good at that) next to valuable rarities, “to take the curse off the good things!” Two mysterious-looking succulent plants like enormous cacti in Chinese blue and white planters turn out to be painted wooden bits of Indian mischief, and the cushions on a banquette are made from hand-woven dishcloths he found in the window of a shop selling kitchen stuff in Ahmedabad. These cohabit amiably with objets de vertu and proper treasures such as the discreetly placed little oval-topped North German ormolu and alabastro fiorito gueridon table (probably made in Berlin or Potsdam around 1800) with a pierced palmette cast border and frieze that he has promised to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. More treasures . . . the mantelshelf supports two ravishing Flemish late seventeenth-century busts of warriors, a male and a female, probably representing Mars and Minerva, in white and black stone marble on variegated red, black and grey and pink marble socles. They are quite at home here, surveying their territory, but each summer he lets them go off for a sojourn in the Met.

Although he says, with disconcerting honesty, “I’m a person who wants; I’m a wanter and a needer,” he is a generous giver. His impressive collection of orientalist paintings and some of his furniture have been bequeathed to the Met, where there is a room named for him. “I have no children, so the world within my gallery will be my children.”

Well, the world has always been his oyster. He was born in Detroit in 1932, “a Depression baby,” visited Manhattan with his mother when he was fifteen and “fell madly in love with New York and that was that; I was never going back. I was an only child. I was a princeling.” He smiles. “I have abdicated.” He hasn’t. He went everywhere, in every sense – he was an inveterate traveller as well as party-goer – knew everyone, hung out with the Duke and Duchess of Windsor in New York and France, was sketched by Andy Warhol in earlier days when he was designing shoes and Andy was drawing them, appeared in Warhol’s films, and when in 1974 he married one of the beauties of her generation, an exquisite called Nicky Weymouth, he put the fashion feathers all a-flutter. (The rumor was that Beatrix Miller, the editor of British Vogue, had suggested the marriage, but in fact they met through Andy Warhol.) Nicky was the only Englishwoman I knew who wore Paris couture, and he has always been impeccably groomed. Together they were a destination style-sighting.

In a corner of the salon, the cushions on the curved banquette are made from hand-woven dishcloths KJL found in Ahmedabad. The table was handmade for him in Agra. The second of the two matching pediments frames a door that leads to the dining room and his library and bedroom.

He has been collecting since he was a boy – “even as a teenager I used to covet and collect little ivory animals – worthless things but pretty, and coins and stamps and cigar bands – whatever happened to those?” He holds out no hope for the addicts among us. “Once you buy two of the same thing you’re a collector.”

The first painting he bought and still loves is a portrait by Jean-Léon Gérôme of a Bashi-bazouk wearing a multicolored ikat and cone-shaped turban, with a fair few dangling tassels and gleaming weapons about his lovely person. Gérôme had an abiding fascination with these mad mercenaries of the Ottoman army who fought like the devil. I look them up: their name means “damaged head” or “crazy head,” in the sense of uncontrollable and disorderly. No discipline whatsoever. “Yes, they were very naughty,” he observes equably. He too seems to have a yearning for the exotic sensual world epitomized in Gérôme’s paintings; and then too orientalism is a form of romanticism and KJL was a New Romantic before it was new.

Everything here has a provenance as well as a personal back story, sometimes capricious. The curious scarlet corded, leopard-covered chairs on each side of the fireplace he saw in a flea market in Palermo – “the chairs cost nothing so I had them brought back and covered them in the most expensive fabric you can imagine.” The fabric was made by Maison Le Manach, a dream of a fabric house founded in France in 1829, which can recreate any fabric – for a price. But the fabric on the chairs is nothing to the tiger-skin fabric, also from Le Manach, that covers the big pouffe at the other end of the room. This pouffe came from Pamela Harriman when she gave up her Fifth Avenue apartment. “It would cost $40,000 or $50,000 now to redo it,” he muses. The needlepoint wing chair nearby, found in London at Christopher Gibbs, is the focus for another congenial seating area in front of a large ornamental bookcase with a carved pediment.

He has managed to make this huge room into an intimate, satisfying and charming place – the perfect backdrop for his parties. “I like to have people around,” he says, in a bit of an understatement. “The dining room can seat eight or nine people but in here there can be forty. Sometimes it gets out of hand and there are almost seventy.” His apartment is an affirmation of delight in the richness of things.

Oh! One last thing . . . a playing card – the seven of hearts – is stuck to a corner of the ceiling so high above. It’s never fallen down and it has been there for years. “A magician just spun it up,” he says, as if it were normal. “It was one of his tricks. Don’t ask me how, darling, I’m not a magician.” Oh, come on!

A corner of KJL’s bedroom. The overmantel and fireplace have a faux ebony surround modelled on the Empire-style doors of Comtesse Marie-Blanche de Polignac’s library.

KJL designed the staircase to the mezzanine.

The plates on the dining table are copies of 19th-century Iznik pottery. The lamp is 19th-century American, and the sculpture behind is by the Danish artist Bertel Thorvaldsen. Two Chinese seats flank what KJL describes as “an unimportant cupboard.” Not an adjective often used in this apartment.