Russell Maret & Annie Schlechter

The dining table was a gift from Russell to Annie, in lieu of a wedding ring: it’s also round, and more useful to her. On the walls are pastel color drawings by Russell, a large, inscrutable photograph of A Bus Stop in Denmark by Dylan Chandler, and the text “ELEVEN ELEVEN ELEVEN,” Annie and Russell’s wedding date, designed and given to them by Marianna Kennedy. The chairs were found at a shop in Brooklyn and painted in a “Jean Prouvé-ish” black. The striped fabric came from the old 26th Street flea market. And the gnomes came from an under-$10 Secret Santa swap.

It’s quite a climb up to Annie Schlechter and Russell Maret’s apartment. A fifth-floor walk-up. Annie runs up and down it ten times a day and is never out of breath. Cool as a cucumber. Races around New York on foot and on her trusty bike as if she were Jet Ankle, with, as they say in Ireland, never a bother on her; it’s her home town, she knows it all, in and out, back and forth, and she never seems to stop. She cooks, she shops, she marshals, she helps people out of crises, she’s the super of her walk-up building, but most of all she works, photographing all over the world.

So. She is a photographer. She uses natural lighting and doesn’t rearrange or disturb her subjects. She invests every subject with a rare balance of excellence, delicacy and dynamism.

I ponder on what Russell could be called. An artist for sure, in a rarefied vocation making fine press and artists’ books, making books that are works of art, books that are a pleasure to hold, to look at, to puzzle over and to read. A typographer? An alphabeticist? Certainly he is obsessed with the alphabet and the miracle of printing. He says, “In 1989 I went to New College of California because they had a poetics program. Letterpress printing classes were being offered as a means for poets to publish their own work. I walked into the printshop at the end of the semester and fell in love instantly. Printing was the only thing I’d ever loved to do. Later, one day in 1996, I had the revelation about designing letters and typefaces.” (Annie interrupts to declaim, “Take care of your own work! Don’t let The Man get you!”) A teacher called Peter Rutledge Koch taught the course and the bottom line is that Russell dropped out of college and started to work for him. “He opened the relationship between the type and the written word and showed how you make the text sing a song.”

Peter Koch wrote, “Art without craft denies the difficult beauty of a thing well made, the elegant simplicity of an idea. Through craft and the precision of design, I seek to bring the rich civilization of the printed book with me to the forge of meaning.” This avowal matches Russell’s ethic and how he goes about his work. Although the printing technology he uses is about five hundred years old, his signature process incorporates high-tech processes, computer-generated drawings and film before they are berthed on the page.

Listening to Russell when he handles his books one hears almost a gambler’s excitement. There is a wonderful secret cabinet in the apartment where the precious and spectacular folders, folios, ribbons, books – some made by Russell, some by other book-makers, some new, some old beauties – are stored to keep them away from the light and from messy fingers.

Their apartment is small, completely relaxed, informal; there’s no family fortune behind it and it’s full of things that both of these sharp-eyed people with wit, discernment and discrimination have found (often in flea markets) and have agreed they want to share.

But every picture, every charming, idiosyncratic and sometimes bizarre thing there has been chosen with an irrepressible cultivated good eye for form, color – and for humor. There are many manifestations of pigeons in the apartment. Does she have a thing about pigeons, I ask, cautiously? She thinks for a while. “I guess I do.” Pause. “I clearly do.” “You don’t know?” “No.” She ponders the pigeon question for a while, then has a eureka moment. She remembers that her grandmother once took the infant Annie out walking in the park and, to make conversation, asked what those birds over there were called. “Fucking pigeons,” she told her amused grandmother. “Well, that’s what my father always called them.”

You can have a laugh at the two frightful colored plastic gnomes in the corner of the living/dining room that channel Jeff Koons in a cheeky fairground fashion but admire the integrity of Annie’s photograph of the Pantheon in Rome.

They swap and trade their work with other artists and the results make for an eclectic collection, including a butterfly from Deyrolle in Paris and a photograph by Marco Breur, known for his radical approach to the discipline. (“He never actually takes photographs,” Annie says, “rather he manipulates photographic paper to his will.”)

There is adherence to the proper look and satisfactory function of things here, good things in good places. There“s something else pretty rare in a Manhattan apartment – the delicious smell of home cooking wafting down as you alpenstock up the stairs. Annie has always had a sensibility that embraces both sides of the Atlantic, and she spent time in Rome photographing dishes by chefs working in the Sustainable Food Project at the American Academy for a series of delectable recipe books. She is a great cook and her kitchen reflects that. I say “her kitchen,” but Russell and she share this house and the tasks in a smoothly interlocked way that creates an agreeable atmosphere of peace and creativity.

They are both deeply engaged in seeking out like-minded endangered arts and crafts fanatics. They don’t go on holidays to get away from it all – they go on workations to get closer to it all: the paper-makers, the hand printers, all those precious people who carry on ancient crafts and techniques that are being subsumed by the digital age and machine age. The striking three-legged oak stools here, for example, come from Rhinebeck, New York State, and are made by a firm called Sawkille Co., using local wood. Sawkille is part of a movement called Rural American Design, whose lead designer, Jonah Meyer, sees himself not necessarily as a traditional woodworker but rather as “a sculptor who happens to be running a woodshop.”

There are two self-contained sections to their apartment – one reserved for their busy creative working lives, the other, across a corridor, for their busy creative home life. “The architect, Joe Serrins, deserves all credit,” Annie says. “He is fabulous. We had a completely different plan, which involved a guest room. He asked us, ‘Do you really want to commit a whole room to a guest who doesn’t come that often?’ Hello.”

In the living room, a wooden packing case rescued from a dumpster was given a glass top to become a sturdy packing table. Bearing the legend “Protect from All Elements,” it speaks of a time when television sets were more precious than they are now. The standing lamp behind the pink sofa was also salvaged by a friend, who rewired it. The large portrait behind the wasabi velvet armchair is a drip painting by street artist Paul Richard, and next to it is a landscape in southern Spain painted in the 1910s by Russell’s cousin, Helen Niles. On the bottom right, the elephant that can fly is by Matthew Austin.

The dining room and the sitting room were separate rooms with a supporting wall between but the Joe Serrins Studio people carved out two spaces so the rooms flow together. The wall between – Annie calls it her Yves Klein wall – is an installation in itself. It is indeed the exact blue associated with that artist. Annie and Russell sourced the paint from the Swiss firm KT Color, which mixes paints to reproduce in a non-toxic form the colors of such artists as Klein, Le Corbusier and Luis Barragán. All the details here are so considered.

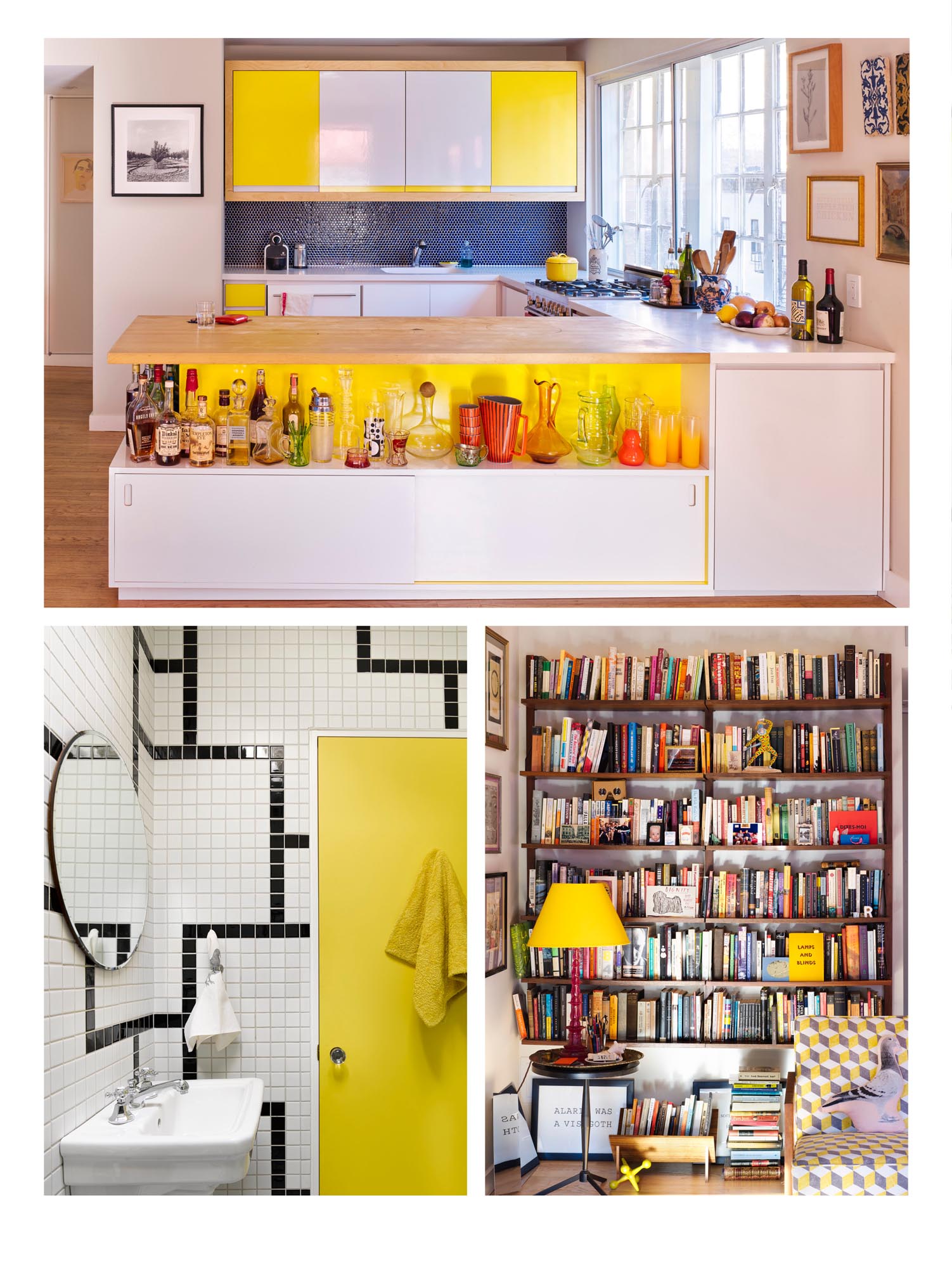

So now a big space with windows on two sides is smoothly divided with, on one side, a combination of living room and a big working kitchen, with countertops made from white Corian and butcher blocks, Formica aplenty and penny tiles (so called because they are ¾ inch in diameter, like the standard penny); on the other side, the dining area, with its green opaline glass chandelier found at the much-mourned flea market down on 26th and 6th Avenue, is hung with paintings, photographs and texts. One piece, “ELEVEN ELEVEN ELEVEN,” is by the celebrated British designer, and sorceress of color, Marianna Kennedy.

Every room glows with color – spring yellows, purple, blue – and pink blinds in book cloth cast a luminous glow over it all. Just look at the American sofa in the sitting room which Annie inherited from her grandmother. She had it upholstered in a Kenzo fabric in the bravest, pinkest pink, and piled it with kaleidoscopic cushions she made herself.

Their apartment overlooks frantic Lexington Avenue and looking out I remember Nora Ephron’s little hymn: “I look out the window and I see the lights and the skyline and the people on the street rushing around looking for action, love, and the world’s greatest chocolate chip cookies, and my heart does a little dance.” And my heart does a little dance in here in this forthright world these artists have made their own.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP In the kitchen, designed by Joe Serrins, Annie and Russell chose the glowing yellow and white of the Formica cabinets and the blue penny-tile splashback; the monochrome photograph of a pear tree is by Annie, and the woodcut portrait in the hall is by Nancy Loeber. A pink resin lamp with a bright yellow shade, by Marianna Kennedy, stands in front of Herman Miller bookshelves bought by Annie’s parents in the 1970s; the oversized yellow-green jack on the floor was inherited from her grandfather; a cushion pigeon sits on another dumpster-rescue chair, now reupholstered in Designers Guild fabric. Russell designed the snaking tile pattern in the bathroom.

Jewel-like fabric by Kenzo covers a sofa that lived with Annie’s grandparents for forty-five years. Annie took the Pantheon photograph early one morning, just before the Roman carabinieri noticed the unpermitted tripod. Beside it are two small gouache portraits studies by Nancy Loeber.