Gini Alhadeff & Francesco Pellizzi

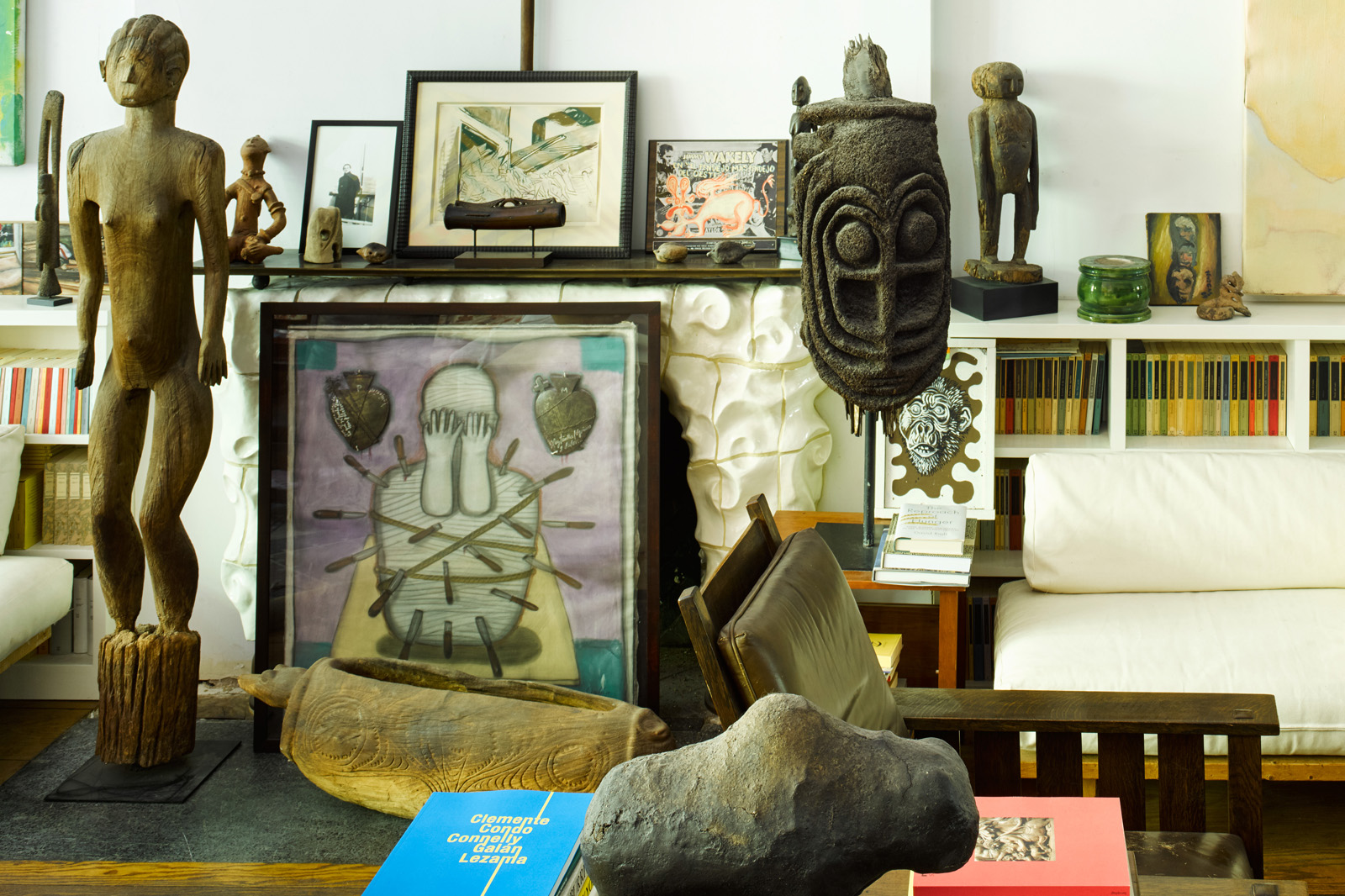

Among the many rare objects in the main salon is the large standing female figure on the left, used as a grave marker (Sudan, Belanda). On the shelf behind is a Tellem figure, from the Dogon people of Mali. Momia con cuchillos, a 1982 painting by Julio Galán, leans against the sculpted fireplace by Saint Clair Cemin. Below is a finger drum representing two entwined lizards from the Trobriand archipelago of coral atolls off the east coast of New Guinea. A boli sculpture – an early 20th-century magical figure, representing a buffalo, from the Bamana tribe in Mali – hulks below a ceremonial house finial in fern wood, from Malekula, an island in the nation of Vanuatu, in the Pacific Ocean. Behind, on the bookshelf, is a standing Sumo female figure from Fiji.

The things that strike one in this house in the Upper East Side are the unbridled intelligence, connoisseurship and timelessness that inform and permeate it. The couple who live here and have created this Shangri-La are Gini Alhadeff and Francesco Pellizzi, distinguished writers, editors, collectors and scholars, with a passionate interest in the cultural life of the world and the art of life; every section of this unobtrusive brownstone, set back in a street just off Fifth Avenue, reveals an astonishing story of their panoramic knowledge, rare eye and devotion to conservation of ritual treasures − ancient and modern − as well as their courteous and gentle way of living with these objects, many of which are sacramental.

They seem to know no bounds in their explorations. Every continent has yielded particular treasures to their safekeeping, and they are also adventurous collectors of contemporary art. Their house is alive with art and books and all the signs of a civilized and erudite way of life. Nothing is showy, nothing – or very little – is shiny. Every room looks as though its history is comfortably ensconced and the garden at the back plays its part too – with gingko leaves making a spectacular yellow ground on which squirrels cheekily pose.

The house has history. It was built in the 1890s and is now a Landmark building. The formidable armor collector Carl Otto Kretzschmar von Kienbusch lived all his life here – ninety-one years – and the great room on the second floor, a salon 23 feet wide and 55 feet deep, was once filled with his collection of medieval arms and armor. Now it is an astounding cabinet of more than curiosities, hosting a fabulous (in the true sense) cargo of objects, furniture and paintings, the whole flooded with light. It wasn’t always so. When he bought it in 1977, “It was a bit drab,” Francesco says, “not immediately so appealing. I like light a lot.”

If, before you enter, you happen to peep into a ground-floor window, your eye will immediately be caught by an early Dan Flavin fluorescent rectangle aglow in a small kitchen. Flavin once said about his art, “It is what it is and it ain’t nothing else.” In this kitchen it is beyond else, perched as it is above what looks like an installation channelling an old-fashioned French bistro – the table with its gingham cloth, the simple 1950s chairs, the random cups and saucers – it’s just their breakfast table, but the ensemble is so witty and unexpected that it makes you smile.

A glimpse of a rare funerary urn surviving from the Mound Builders’ culture, with, beyond it, the boli figure below the painting Ginsberg’s Sassetta by Francesco Clemente and an ancestral figure in fern wood from Ambrym Island, Vanuatu. On the other side of the room is a 19th-century tam-tam from Fanla in Ambrym Island.

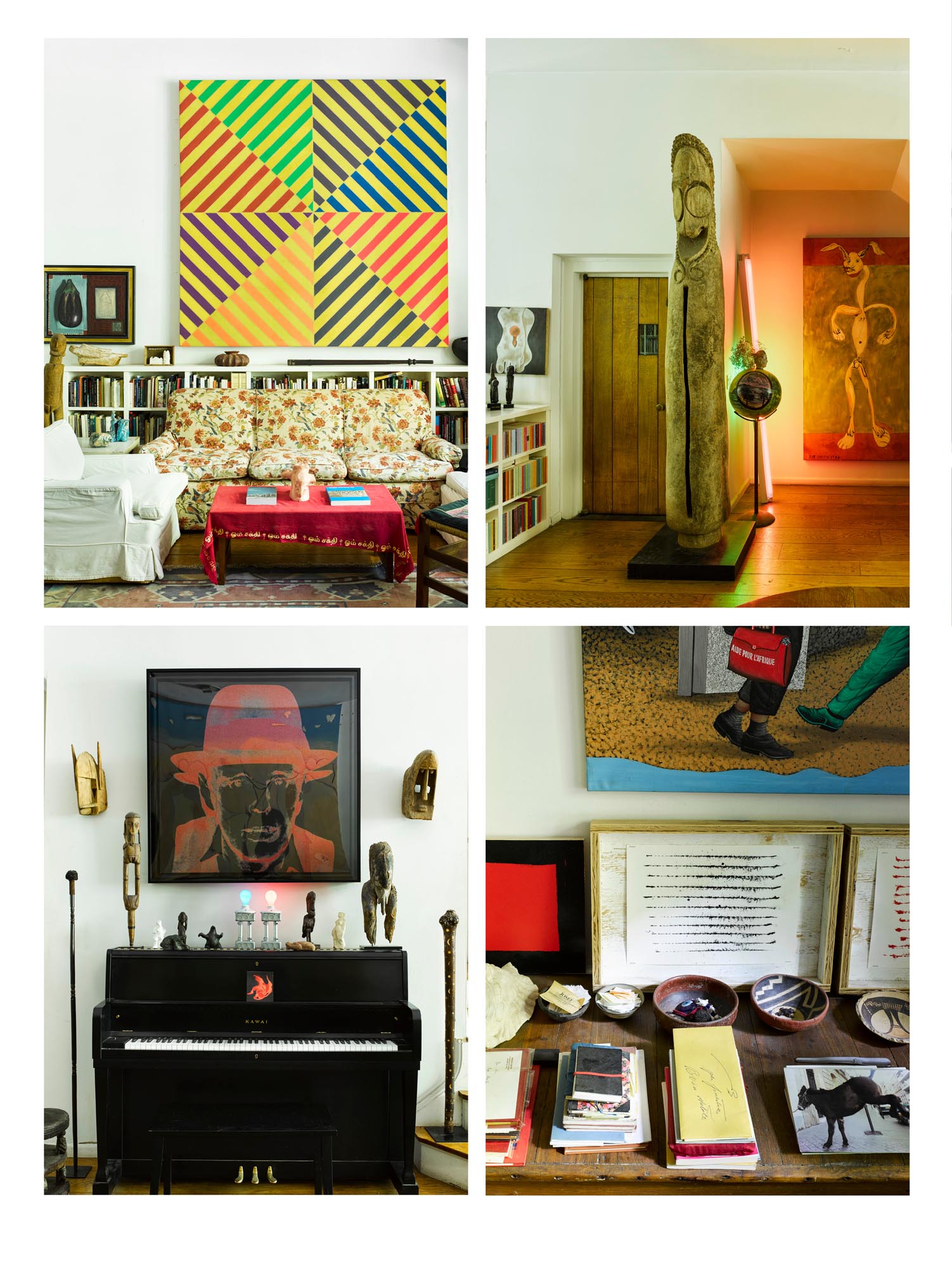

Once inside you stop smiling, especially in the vast salon on the second floor, and just stare. Indeed, you don’t know where to start to look, so full it is of remarkable and rare artifacts, including many from Africa and vanished civilizations of the Americas and the Pacific. The air here is freighted with magic and enshrined memory. It would be easy to think you are in an oneiric state, surrounded by so many singular and esoteric objects, symbols and emblems of funerary cults and rituals from places as far apart as Vanuatu and Mali, side by side with newer emblems like Andy Warhol’s “diamond dust” portrait of Joseph Beuys. (“They met in Naples,” Francesco says, and so they did, for a joint exhibition of their work held there in 1980.) But you are brought down to earth by more domestic nuggets, such as furniture by Gustav Stickley, the designer who founded the magazine The Craftsman and was one of the chief practitioners of the American Craftsman style, at the turn of the nineteenth century.

Superb pieces vie for ranking and prominence. A massive cylindrical nineteenth-century Ambrym Island ceremony slit gong (standing drum) with huge plate eyes – a tam-tam, a funerary object erected in memory of deceased relatives –certainly draws awed attention. But then again those typhlotic eyes stare across at another vision, Ginsberg’s Sassetta, a big, magnificent Francesco Clemente painting. Behind the magisterial tam-tam, in almost comic juxtaposition, is March Hare, a boisterous painting by Ray Smith, with a Dan Flavin vertical tube propped beside it.

And over there on a table, surrounded by books, stands a boli (although stands is too prosaic a verb for the hulking presence of this small object), an early twentieth-century four-legged magical figure, representing a buffalo. Basically built around a wooden frame, caked in libations, sediment, vegetable matter, honey and other natural materials by the Bamana tribe in Mali, a boli is a secret object harboring huge quantities of energy, with magical powers that can be activated by the initiated. This fits with the principle of the tribe that powerful things are opaque to general human understanding, and only the initiated will understand them.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT A 1984 painting by Julio Galán, El Juego (Berenjena) hangs beside a Frank Stella painting, Sidi Ifni II, from 1965 (from the Moroccan Villages series). An untitled 1991 painting by Francesco Clemente; on the other side of the door the tam-tam from Ambrym Island, in front of a ceramic sculpture by Julio Galán, Ya Se (1988) and March Hare (1987) by Ray Smith, both illuminated by an untitled light sculpture by Dan Flavin (1969). Under a glimpse of Chéri Samba’s painting Les Faux Anges are ranged Pueblo ceramics and, behind them, works by G.T. Pellizzi: The Red and the Black No. 50 (2013) and two Snap-Line drawings from 2014. Andy Warhol’s “diamond dust” portrait of Joseph Beuys (1980) hangs above a collection of treasures including three Dogon masks from Mali, a mythological figure from Astrolabe Bay, Papua, New Guinea, a twin-light sculpture by G.T. Pellizzi from 2015 and a tangata manu (bird-man), from Easter Island; on each side of the piano, a twin figures club or staff from the Marquesas archipelago and a club with ivory inlays from the Fiji Islands.

Over the mantelpiece a framed cover by Ray Smith for a 1987 issue of Gini’s magazine Normal. Below, ceramic sculptures by Ximena Garrido-Lecca, Destilaciones VI (2016), and an untitled work of 2015; and, below the table Vahakn Arslanian’s Bad-Tempered Bird from 2006. On the table to the right, works by G.T. Pellizzi include The Red and the Black No. 50. Below is an untitled Julio Galán painting of 1987 and above Chéri Samba’s Les Faux Anges.

Pellizzi understands them. He writes about them, and much else. He co-founded and edited RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, a journal of anthropology and comparative aesthetics dedicated to the study of cult and belief objects and objects of art. His books, those he has edited or published, line the walls of the room. Not that his erudition is confined to tribal and ethnic art: he has written essays for journals all over the world on contemporary artists including Brice Marden, Francesco Clemente, Eric Fischl, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Cy Twombly, Joseph Beuys, and many others, Indeed, if one were to attempt to enumerate Pellizzi’s scholastic achievements in full, time would trickle out, exhausted.

Born in Rome, he studied archaeology and comparative religions at the University of Rome, and anthropology in Paris, under Claude Lévi-Strauss. He was a member of the Committee for Exhibitions of the New York Public Library and organized anthropological conferences the world over. He was a Harkness Fellow at Harvard University, a resident tutor in folklore and mythology, and did fieldwork among the Maya of Chiapas (a southern Mexican state bordering Guatemala). In 1973 he created the Pellizzi Collection of Chiapas Textiles, the most complete Mayan textile collection from the Chiapas Highlands extant. (Perhaps it is no coincidence that his daughter, Aurora, is an artist working in textiles and bronze. Other things in the room that bring Aurora sweetly to mind are the piano she played, and a floating bronze pyramid that she made, and a teddy bear of some twenty-five years.)

His wife, the writer Gini Alhadeff, who smiles and looks like the Mona Lisa, is quietly international, patrician and modest to a fault. The lord knows how many languages she speaks. Her parents were Italian and she was born in Alexandria, went to French kindergarten in Khartoum, learned English in Tokyo, graduated from high school in Florence, and attended art schools in London and New York. “I was sent to Florence and became Italian, England and became English, to New York and became a New Yorker, if not an American. I am the worst of the chameleons: I have swallowed several ethnic identities whole and no single one lords it over the others . . . I sometimes find it hard to distinguish between identity and mimicry.” Her memoir The Sun at Midday: Tales of a Mediterranean Family is an enchanting teasing labyrinthine testament to a ravishing intelligence and sensibility, and (although it contains a harrowing account of her uncle’s sufferings in Buchenwald) it is funny. An aunt by marriage was Mariuccia Mandelli (considered the godmother of Italian fashion), who started Krizia, the first ready-to wear house in Italy. For a time as young woman Gini wore a Krizia scarf over a long sweater and a greenish flannel skirt to the ankles. (“It earned me the nickname ‘the Big Droop’ from a friend who shared my office at the Museum of Modern Art.”) After working for another fashion designer, she writes, “By the time I left I had exhausted the very idea of glamour.” Not true!

She founded and edited, with her husband, two literary quarterlies, Normal, and XXIst Century! (and in 2004 won Mexico’s Pluma de Plata award for journalism). Those quarterlies – with the work of artists spread over the pages before the texts were added – are a true integration of art and literature. They are collectors’ items now.

She worked as a travel writer for over twenty years and edited and co-translated My Poems Won’t Change the World by the treasured Italian poet Patrizia Cavalli. Gini Aldaheff writes and works constantly (else, “one would die, as you very well know!”) and has two new books on the way, one about a Swiss-American psychiatrist who built a garden of concrete follies with her patients at Bellevue Hospital, the other a memoir about the incantations of the New Age.

So it’s no surprise that this house is a treasury of past and present cultures. But comfortable and unpretentious too. I ask about the handsome side table, above which hangs the illustration by Ray Smith of his cover for an issue of Normal, and Gini says, “I saw it discarded on a sidewalk and took it home and it pulls out to make a much bigger table.” We both stare at it with respect.

In the big salon, near the stained-glass windows overlooking the street, is an inviting sofa, covered in old-fashioned chintz, with chairs drawn up as though a conversation has just ceased. The conversation could have been about the Frank Stella painting Sidi Ifni II, 1965 (from the Moroccan Villages series) hanging just above, facing the polyptych on wood by the Mexican painter Claudia Pérez Pavón. Other paintings include Les Faux Anges by Chéri Samba and a tinted photograph by Luigi Ontani called GariBalDanz (a play on the figure and name of Garibaldi), and which is by way of being a self-portrait. An early painting by Julio Galán (el niño terrible of Mexican art) stands in front of the commissioned ceramic and bronze fireplace by the Brazilian sculptor Saint Clair Cemin.

Perhaps the most subtly beautiful, and in a way woeful, object in this room is a funerary urn from what is now the state of Georgia, an extraordinary example surviving from the cultures collectively called Mound Builders. For thousands of years the peoples of these tribes constructed various styles of earthen mounds for religious and ceremonial, burial, and elite residential purposes. This lovely object is from the Adena culture. “It wasn’t dug out; it came out intact from the ground. It’s very fine,” Francesco says with unemphatic authority. “I got it through George Terasaki, a dealer in American Indian art.”

Terasaki had his refined gallery not far from where the Pellizzis live and was renowned as the best private dealer, with museums as his major clients. He was a practicing artist until 1960, when he saw some Navajo textiles. “I realized it was great art,” he said. “At that time American Indian art was something looked down on.” He bought astonishing objects, paying from $5 to $5,000, from thrift shops, rug dealers and antique stores, things that today are revered by collectors and connoisseurs. The same could be said for many of the remarkable rarities in this Manhattan house.

I don’t think either Gini or Francesco has ever considered monetary cost as having any value. They consider worth. She wrote epigrammatically in her lovely book, “I see as I write.” They see as they live and they both live with an acute awareness of the sacred history of humankind.

The kitchen table, like something in an old French bistro, hangs Dan Flavin’s A Primary Picture (1964).