Barbara Jakobson

In the double-height living/garden room Jeff Koons’s Winter Bears stand sentinel against the view of an enamel paint-on-steel sculpture by Stefan Knapp. The ghost shadow of Frank Stella’s relief Felsztyn III (1971) soars above the 1970s classic “Non-Stop” Italian sofa, the DS-600 for the De Sede company. On the wall opposite, an inscription by Lawrence Weiner and a blue fluorescent piece by Dan Flavin and, on the floor, Carl Andre’s Copper-Copper Plain.

If you maneuver down the steepish staircase to Barbara Jakobson’s double-height central room, an astounding crate of air and much besides, and you’re looking out at (“what are those in her garden?”), you’ll soon be stopped short by Con Ed orange and white barriers (Alarm! Stop!! Look!!!). These ubiquitous symbols of New York’s energy company are here transformed and transforming by being used as the edging to the installation posing as a cocktail bar by artist Tom Sachs. They are an apt metaphor for many of the things in this house. Not that you’d easily find yourself down here, since on the way you would pass so many things to warrant your total attention (Stop! Here!! Now!!! Look!!!)! And total attention is her philosophy – although she might eschew the word. “If you inhabit the world by being aware of its artifacts, whether you’re out on the street or inside a supermarket, you’re likely to have a much better time. All you’ve got to be in this world is a noticer. You just have to notice what everything looks like.”

But let’s rewind the movie and come back up this midtown street on the East Side lined with brownstone houses, so beloved of many New Yorkers and so often vilified in print. Edith Wharton haughtily pronounced that they were built with the most hideous stone ever quarried, and in the New Yorker writer Brendan Gill was even more hostile: “Let the wrecking ball of the present tumble the mediocrities of the past . . . little in the 1960s is apt to surpass in stultifying dullness those uncountable blocks of cheap, speculator-built nineteenth-century brownstones.” Owners of these now cherished (and fabulously expensive) houses would not thank him for that command.

You know it’s Barbara’s house ahead because you’ve already been inundated with quotes about her originality, her signal place in a golden New York art age, her span of knowledge – and her sense of fun. This house has two squirrels perched on the pillars outside its door. Lead, as it turns out, but totally lifelike. And a frieze of metal squirrels scampers across the facade. The lead squirrels are by the sculptor Jane Canfield, the frieze is to disguise a crack in the wall. This entire frolic is typical of Barbara. Passionate, generous, restless, for decades she has been one of the brightest stars in the art firmament as a vatic collector, enabler, advisor and mentor right at the heart of cultural and curatorial art life in New York.

Walking down the street with her is an education. She’s in black leather today and young men stop and congratulate her on her look; she always was a beauty and she still is. (There’s a ravishing photo of her by Horst seductively draped in a Carlo Mollino chair and a vintage Dior evening dress, a Robert Mapplethorpe quadriptych of her as a young beauty in 1977, and a 1983 Mapplethorpe in which she looks sleek as a seal.)

Fellini once said: “the visionary is the only true realist,” and Jakobson is a realist by that definition. She is brisk in her knowledge of and love for art of the twentieth century in all its aspects, a deal of it made by people she knew and who were her friends. And visionary? She is not only constantly tuned in to her time and place, she’s also ahead of the curve, anticipating shifts in taste, spotting new talent, buying in the forefront.

She once said, “I“m a person who wants to be engaged in the intellectual and cultural life of my time in more than simply a superficial way.” And she is coiled into that life and time. You’d have to snip a lot of the threads that bind a culture together to get her standing clear. She has been a trustee of the Museum of Modern Art, serving on many and varied committees including Painting, Sculpture, Architecture and Design. She’s served on the International Council of MoMA, the board of the Architectural League of New York, the Visiting Committee to the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University. As head of the Junior Council of MoMA she organized a groundbreaking exhibition of architectural drawings; chaired poetry evenings with John Giorno, Joe Brainard and John Ashbery, and performances by Laurie Anderson, Steve Reich and Philip Glass. As consultant to Knoll International she enlisted Frank Gehry to design a group of chairs and tables for the company and oversaw the project.

The Argentinian architect Emilio Ambasz, then curator of design at MoMA and an early proponent of “green architecture,” encouraged her interest in architecture, and James Stirling, Richard Meier and Cedric Price were among her friends. These architectural adventures are reflected in her house, in its layout and function, its accord with the freewheeling art and seminal pieces of postwar and contemporary art which line it top to toe − five stories up from garden level. I note a drawing by the visionary Cedric Price on a crammed notice board as I walk up, past a library office called the Transportation Room, full of images and objects that move, models of planes, cars, trains and automobiles and stunning early posters for American Airlines (slogan: “Every hour on the hour”). She has her veuvière at the very top, like an aerie – with her study, and an eccentric back-to-front library designed in 1974 by Emilio Ambasz.

Her spectacular bedroom, with its Lucite furniture, is almost dominated by a photograph of a room with leopard-spotted walls and a symbolic army of 316 butterflies in cases in Carlo Mollino’s mysterious shrine, Casa Mollino, his secret apartment in Turin. It is now a private museum and has been described as a modern day Egyptian Book of the Dead. He never lived in it and no one knew of it till after his death. Here it opens a bedroom in New York into a puzzling, other and esoteric world.

On one wall of the hall Julian Schnabel’s What To Do With a Corner in Madrid towers over a day bed by Rachel Whiteread and a fiber and polyurethane vase by the Campana brothers, while on another a Jim Dine portrait of Barbara hangs above a drawing by Eric Fischl. To the left of the painting is a Frank West “Uncle” chair. The framed drawings in the arched doorway are by Jőrg Immendorf, and a William Eggleston photograph can be glimpsed through the alcove.

When Barbara Jakobson encounters new art she embraces it as a complicated intellectual challenge demanding new alignments of her habits and sensibility, and the origins of that sensibility lie in how and where she grew up. She was lucky from the start in her environment, culture and nurture, born as she was across the street from the Brooklyn Museum and with visionary relatives who encouraged her in her passion for looking. As soon as she was old enough she escaped to the museum as much as possible. She was transfixed. “It was my way of imagining myself in a place other than the one in which I lived, and that was a frequent necessity for me.” The place in which she lived was a pretty apartment, filled with fine English furniture in good quiet taste. “I think that my attraction to modernism came as a form of reaction and rebellion against my mother’s taste.”

She lived, in her own words, “in the hothouse of the imagination.” Her older cousins Donald and Harriet Peters became her first mentors. “I was just growing up. It was the mid-fifties and they took me everywhere and gave me license to become involved with contemporary art. And in their house I’d see paintings by Hans Hofmann, by William Baziotes, by Robert Motherwell. Once I saw this little painting of a white number 4. I said, ‘What is that?’ It was a Jasper Johns.”

They introduced her to the crucial gallery owners of the time, including Leo Castelli and Ileana Sonnabend, and later she became great friends with Sidney Janis, another legendary dealer. “From my early twenties, I started buying things and taking them home and making them my own.”

So this house in which she has lived for fifty years is an almanac of New York art weather, recording storms, tornadoes, high winds, maybe even sunny days, over the last decades. It bulges with surprise, intelligence and energy and is infused with wit. A looming Robert Morris felt sculpture hangs gravely in her hall near the dancing sunlight of an Eric Fischl drawing and an imposing Julian Schnabel. In the balcony – within the house, overlooking the big room – a rug by Barbara Bloom, a simulacrum of that famous green Olympia Press paperback cover (what a thrill the sight of that used to give to a convent school girl) is the anchor for the confounding furniture sculpture Chair by Richard Artschwager, made from red oak, Formica, cowhide, and painted steel. (I’d advise the unwary not to try to sit on it.)

Tom Sachs used carefully chosen and labelled bottles and Con Edison barricades to make up the cocktail bar art installation, surrounded by BassamFellows bar stools and a rug adapted from a photograph by James Wellings.

A 1970 felt sculpture by Robert Morris hangs against wallpaper commissioned from Peter Halley.

A work by Matthew Barney above Sebastian Errazuriz’s foldable Occupy 2012 chair.

A 1977 quadriptych portrait of Barbara by Robert Mapplethorpe hangs above a Lucite and patent leather “Corset” chair by Grosfeld House.

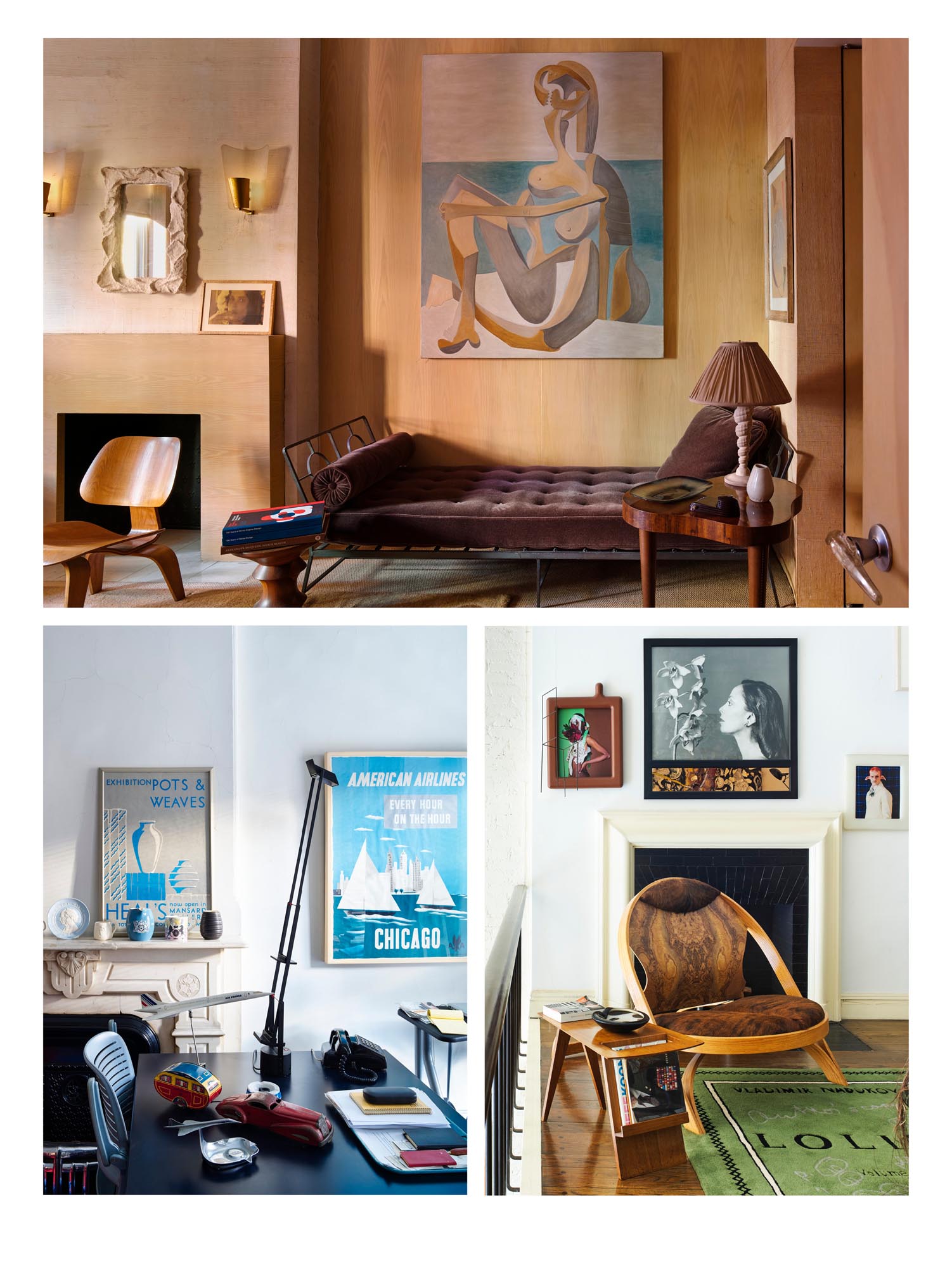

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP A Charles Eames chair sits below a Diego Giacometti plaster mirror flanked by Italian sconces from the 1950s. Not Picasso, a painting by Mike Bidlo, hangs above the Salterini day bed. The table is by Gilbert Rohde. Two works by Matthew Barney flank another portrait of Barbara by Robert Mapplethorpe; Chair, a sculpture by Richard Artschwager, sits on the cover of Lolita, realized in a rug by Barbara Bloom; next to it, a side table by Jens Risom. On the mantelpiece in the Transportation Room, Poole pottery and British royal souvenirs, including an Eric Ravilious Wedgwood Coronation mug, stand in front of a 1930s poster from Heal’s Mansard Gallery; to the right, a similarly iconic poster for American Airlines; on the desk, a Tizio lamp.

A table by Danish-American designer Jens Risom, one of the first to introduce Scandinavian design to the United States, is next to a piece by the Campana brothers – a terrifying vase that looks like a glass Medusa.

There’s a kind of jubilation about the placement of art on every floor, an understanding of its aesthetic functionality. I have never been in a house with so many personally significant and historically personal pieces. It’s an archive, of course, but there is nothing static or fixed about it – it breathes the energetic genius of its owner. The Diane Arbus photographs for example – she and Diane Arbus had been friends since 1958, when they met as young mothers in the Central Park “Mommy Playground,” and she would often look after Diane Arbus’s daughter Amy in her pram while the photographer roamed the paths looking for subjects.

She and her husband, John Jakobson, a financier, bought this house on a freezing day in 1965. “We’d looked at a lot of brownstones and then came into this and bingo we bought it in a minute.”

The house has form. Elia Kazan lived here in the late 1940s, sold it to Peter Gimbels, heir to a famous department store, who made the revolutionary double-height central space and the steep staircase. Billy Baldwin, the dean of American decorators, did it up for Gimbels. “What was it like then?” I ask, sitting in the great amplitude of space that is her living/garden room, an art lover’s paradise; eclectic, educative and severe all at the same time. “A garden room,” she says and then in a wicked comical précis, “like a set in Auntie Mame. White-fur-coated stairs, green chintz and bamboo and wicker.” (Baldwin once said, “I certainly made a lady out of wicker.”) It’s now cosmically removed from his version. A curving “Non-Stop” sectional sofa, the DS-600, designed in Italy in 1972 for the De Sede company and looking as long as Italy itself, sits opposite the faint typographic text WATER UNDER A BRIDGE, inscribed on the wall by sculptor Lawrence Weiner, one of the central figures in conceptual art in the 1960s, who uses language as material for construction. (If you buy a Lawrence Weiner wall installation, a team of signwriters paints it where you want it. The typeface is determined and immutable so you are buying the phrase entirely and as it is, along with the essential unique certificate of authenticity.) Just below the text is a Dan Flavin fluorescent piece from 1964, and on the floor there is a table by the maverick designer and sculptor Paul Evans, “the wild card of late twentieth-century modernism,” who worked mainly in metal. This sleek, high-tech table comes from his Cityscape series; another of his pieces, the Broadway chair, is in a bathroom.

She has reinvented her rooms over and over again. “I’ve always had an obsession with rooms and particularly rooms designed by the great women decorators – Elsie de Wolfe, Madeleine Castaing and Marie-Laure de Noailles’s commissions of Jean-Michel Frank. These were some of my sources of inspiration. I guess if I have any talent at all it is in the creation of rooms, which is what I’ve done over and over and over.” Floor after floor bears witness to that one of many talents: even the wall textures of the rooms are artful – plywood next to ribbed plaster, say – giving a feel that is different from what is being displayed.

There’s also a lot of tapping into contemporary ethical movements. Although sculptor Tom Sachs apparently innocently and lightheartedly recycled those Con Edison barriers and old lumber to fashion the counters and surfaces of the installation masquerading as a tempting and well-stocked bar, he was making an intrinsic statement about the conceptual underpinnings and principles of his work, exposing how it was built, “the scars of our labor,” and his system of making things out of recyclable material. (He also labelled every one of the many capitalist liquor bottles on the counter.) The bar stools are part of the artisanally inspired furniture range made by the design team BassamFellows. These modern classics are based on an old Swiss tractor seat found on the side of a road.

Another witty but serious piece, ostensibly a wood and lacquer folding chair – is an Occupy 2012 piece by designer and artist Sebastian Errazuriz on which is painted a simple didactic question and command: HUNGRY? EAT A BANKER. In Errazuriz’s work things are never quite what they seem, and his experimental style provokes thought and comedy. (Never mind cannibalism.)

Then too Frank Stella’s famous apothegm “What you see is what you see” doesn’t quite work here, even about his own work. For years a Frank Stella wall relief – now sold – held sway over a white wall in the big room, and each time the paint was refreshed the outline was carefully and closely painted around. What you see is a ghost of a big formidable thing – a phantasmagoric Stella.

Sold? The painting was in a sale devoted to Post-War & Contemporary Art and Design from her collection at Christie’s in 2005. “The impulse . . . was to look at an empty room again, pure and simple.” My mouth hangs open. A catalogue full of important stuff has gone and yet the house still has all these pieces? I love collectors. Insane.

Adam Gopnik, that brilliant essayist, once wrote: “A major divide in twentieth-century art is between those who got the fifties and couldn’t get the sixties and those who got both.” Barbara got both with a vengeance. Indeed, nimbly hovering over the fault line, she saw the break take place and jumped it with an unbroken stride. “I see collecting as a form of autobiography, as evidence that I lived for most of the last century and then into the new century. It’s my way of staying engaged with the world and also a way of staying engaged with myself.” She still loves abstract expressionism and Frank Stella and Jasper Johns, and there’s a 1966 copper tile Carl Andre piece on the floor, a Jean Prouvé chair (part of a set she once owned), Frank Gehry chairs and the singular book donkey made by Ernest Race, the English textile and furniture designer famous for his steel and molded wood chairs on which, it seemed, sat half the population of Britain during the Festival of Britain in 1951. There’s more. Much more.

There are also pieces by young artists at the beginning of their careers and as they progressed: William Eggleston photographs; screen prints by Andy Warhol; a day bed by Rachel Whiteread; one of an edition of Jeff Koons’s early works, Winter Bears, from a series of sculptures made for an exhibition, “Banality,” in 1988. (Another Winter Bears is in the Tate Gallery.) Some see Koons as the bully in the playground, the class clown. Barbara says: “He’s brilliant. Like all original artists he mines art history – they’re the greatest thieves . . . if you know art history and you’re a reconstructionist . . . this is a classic diptych. It’s pop art and everything else and he’s one of the most commanding artists to come down the pipe in the last few years.”

She’s always had a lot of moxie, never hesitates. “I never had any trouble making choices. Whether they were right or wrong they were my choices and that was that.” She has always taken off, travelled everywhere, in pursuit of what she was interested in, and many of the pieces she bought were off the easel or out the studio within a year of their making. There is, of course, the odd maverick – a table by Edward Wormley, whose furniture represents an early convergence of historical design and modernism, sits happily near a Gio Ponti desk and magazine rack in her office, and Paul Frankl chairs hold their own with the prototype – yes the 1997 prototype – of the revolutionary knotted chair by Marcel Wanders made from lengths of hand-braided aramid and carbon fiber cord infused with epoxy resin to give it rigidity and strength. Wanders himself calls it “a little miracle.” An example is in MoMA.

Looking out through the full-scale window downstairs to the white garden boundary wall you are accosted by a host of vivid enamel decorative panels. I recognized them, with nostalgia, as having been on the facade of Alexander’s department store opposite Bloomingdale’s decades ago. These disregarded shopfront pieces turn out to be archetypal examples of the work of Stefan Knapp, a Polish painter and sculptor who worked in England and developed and patented a technique of enamel paint on steel. Barbara, being Barbara, rescued them when the building was demolished. Never a better example of her belief that “if you’re a highly visual person you interpret the world by looking at it, or looking at its artifacts.”

In 1979 she was dazzled by Stilnovo, a book by the architectural historian Christian Borngräber about the imagination and fantasy of furniture and general design in the fifties. He became a close friend and under his influence she started collecting singular and important fifties furniture and industrial design objects. “Though I love all furniture I decided early on I had to live in my own time. And that is what collecting allows one to do – if you acquire things that relate to your own life, you have a much more significant attachment to them. What made me want to buy this furniture was its biomorphism. In a way it’s like surrealism on legs. Suddenly those liquid fluid furniture forms were so appealing to me like Dalí’s melting watches I’d seen at the Modern so long ago, and I think they’re still appealing.”

Barbara’s Grosfeld House Lucite bed and bedside table.

Examples abound of the interlocking and omnivorous worlds of design, fashion art and furniture. She hunted down the chairs made in brass and resin flex that Carlo Mollino designed in 1958 as a wedding present for Gio Ponti’s daughter Lisa. Only six chairs were made as part of a suite. The eyes of different beholders read this chair differently. For some it is brazenly erotic, other see a cloven hoof back attesting to his fascination with the occult. Barbara’s Lucite and patent leather “Corset” chair, made by the New York company Grosfeld House (pioneers throughout the 1930s and 1940s in the use of Lucite for furniture – which I fear are called Glassics), seems almost the precursor of the Mollino piece. In her bedroom are more Lucite pieces from Grosfeld House, including the glamorous headboard and beside tables.

On every floor there are pieces freighted with history. Take, for example, the “Mexican Bookshelf,” designed by the French architect and designer Charlotte Perriand in 1953 for the Maison du Mexique at Cité Internationale Universitaire de Paris. This is often attributed to Jean Prouvé (it was produced by Atelier Prouvé), and his name attracted higher bids at auction. It is only quite recently that Perriand’s fundamental importance as the author of great pieces has been fully recognized.

“Everything I acquire somehow relates to a memory of my own life. If I get it, if I buy it, if it becomes a part of my life, it’s because somehow it’s tipped off some unconscious sensation, and I know that a lot of people who relate deeply to art have this sensation. It’s not unique to me, it’s described by others.”

She carries a swathe of knowledge of modern art and design in her head. It is her real subject, and everything she does in her life’s work is both a critique and homage to the true thing.

So when you walk though this house and through its rooms you’re not just walking through rooms or even a retrospective look at a life. You’re walking through a continuing, felt, intense, immediate, direct, vivid autobiography; autobiography mingled with memoir and with unwritten chapters in waiting, waiting for her next swoops. The medium in which it is written is her life, the consequence of a profound, relentless, unquenchable need. “If you said to me, what do you want more than anything I’d say – Surprise me. I want to be surprised by the future and I hope I am.”

The focus of Barbara’s bedroom is an enormous photograph of a room in Carlo Mollino’s hidden apartment in Turin. In front of it, a Regency sofa and a Grosfeld House chair.

In the bathroom are two Warhol screenprints: Nixon, which is part of a large edition made in support of the McGovern campaign; and Liz, signed and dated 1965.