The Fonseca Family

The main studio, now the living room, built in the 1880s by Daniel Chester French. A kilim hangs over the high balcony studio. Below stands a French medieval stone madonna. The painting of The Boy with the White Column was done by Bruno Fonseca in 1981. An old gilt Egyptian chair sits beside a junkshop find. The limestone sculpture is by Gonzalo Fonseca and on the easel stands a big green picture he painted in 1961. The old American mannequin is beribboned by Elizabeth Fonseca.

This high, glowing sunshine-yellow house in the heart of the West Village, with its mews and skewed streets, remains, at least for the moment, much as it was in its heyday; but for a time it was quiet, as though dreaming of how it was when a family of artists – parents Gonzalo Fonseca and Elizabeth Kaplan and their four children – lived in it, and of how their friends, so many of whom were artists, were drawn to it, from the late 1950s until quite recently. When the young married couple, Gonzalo and Elizabeth, first moved into the house they were joining and extending a century-old artists’ scene in the Village, which was full of intellectual, artistic and literary productivity. These particular high walls contained a corresponding and shining hive of creativity.

The house is filled with paintings and treasures, many made and painted by the family. Other treasures were amassed from the travels Gonzalo and Elizabeth made together — to Europe, Africa, down the Orinoco river and to other parts of South America. And of course to the further reaches of the junk shops on Bleecker Street and auction houses on Second Avenue which still existed in those days.

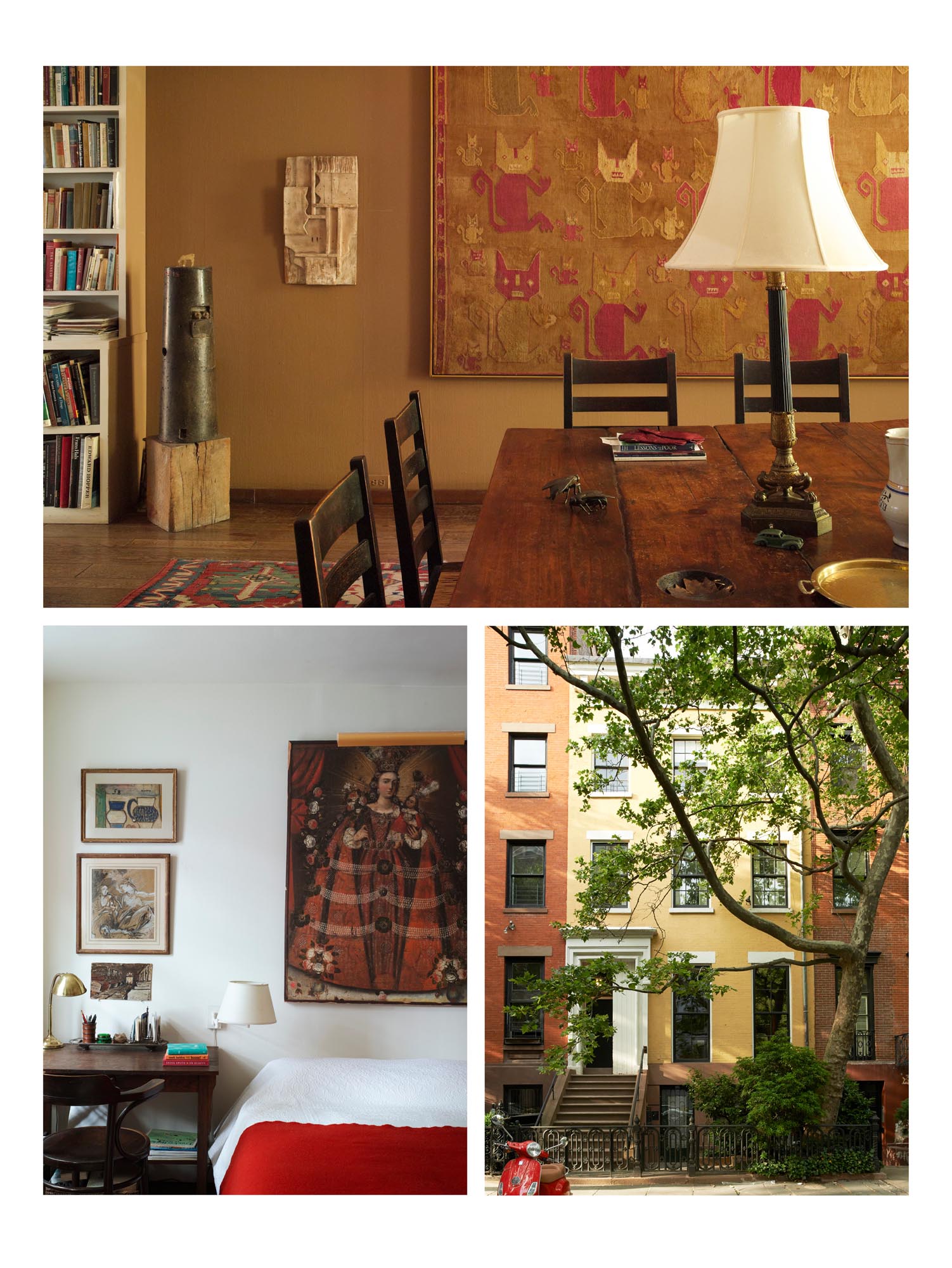

One of the rarest things in the house is a painting full of equilibrium and soft power, a rosy-hued Peruvian icon called the Cuzco Madonna, from around 1750; there she stands in her frame in a bedroom in her great robes of state, looking wary and vulnerable, but also at home.

Gonzalo Fonseca, a celebrated Uruguayan-born sculptor and painter (he became an American citizen) was obsessively interested in everything that could irradiate his work; Pre-Columbian art, ancient ruins, quarries and archaeological sites (as a young man he worked on an excavation in Syria), European and American art and a theory of art developed by his teacher, the Uruguayan constructivist painter Joaquín Torres García, and based on universal symbols. He used it all in his own visionary way – in his paintings and in his hewn and carved sculptures, in wood, in polished granite, in limestone travertine and marble, along with any brownstone he with the help of his sons managed to recover from New York’s rich demolition sites. Oddly buoyant in feeling for all their heft, they range in size from small-scale stone miniature buildings that forge a link between sacred and secular, between house and temple, to massive works such as Torre, the 40-foot-high cast-concrete tower he designed and built for the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City.

He used ladders in his works, biblical stairways to his earthly heavens, and stuff that he gleaned from the surroundings of his life – round stones in square windows; objects tied with string, like pendulums, or giving the look of a basket being hauled up in a medieval city; or Lycian tombs; or like something that fell from the front of Mesa Verde – beautiful hauntings, sculptures, the playthings of a strange but lucky child. He made little distinction between sculpture and functional objects like the breadboards he made from old chair seats or the stone mantel he carved for the fireplace in his study in the sitting room on the third floor with its recesses for his pipes or in the dining room table he made from salvaged railroad timbers. That family table is like a palimpsest of the history of the meals in this house, with the imprints of years of use, the marks of children casually chiselling little symbols or their names into the surface and a dark declivity where a saucepan burned a hole in the middle of the table.

Those children were beautiful and talented. Quina, Bruno, Caio and Isabel Fonseca are singular artists, although Isabel does not work in the plastic arts – she is an acclaimed writer. Quina is a nanosecond high-energy designer – described by Isabel as “a maker of exquisite things.” Some of her textiles are on the sitting room sofa, presents to her mother, and beautiful they are. Bruno a gifted figurative and abstract painter, died in 1994 aged only thirty-six, and his death is a fault line in the family. His work is in several public and private collections, including that of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and he had a posthumous retrospective, “The Secret Life of Painting,” in the Brooklyn Museum of Art in 2000. His work resonates throughout the house.

Caio is a much-admired painter. His passion for music, and his talent for making it, is second only to his painting. (His parents were startled to hear him when he was seven years old quietly whistling a perfect rendering of Schubert’s Trout Quintet.) His work hangs in the permanent collection of the Whitney Museum, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in the Smithsonian in Washington, DC, and the Houston Museum of Fine Arts.

It’s as if the whole family lived by Philip Larkin’s great line “Originality is being different from oneself, not others.”

And this family really has form. To go just a bit further back in the family tree: their maternal grandmother, Alice Kaplan, was an accomplished amateur painter, a philanthropist, a trustee and president of the American Federation of Art and an unerring and passionate art collector. Once, going to an exhibition in the Fuller Building of galleries on 57th Street, she stepped out of the elevator on the wrong floor and found herself in another gallery showing the work of Egon Schiele – his first exhibition in the US. She bought the show. She was right on target when she bought paintings by the (then unknown, now renowned) American journeyman portrait painter Ammi Phillips, who died in 1865 and was forgotten for decades. (She did regret, though, that she had not bought a beautiful little Cézanne when she could have done.) And then too their grandfather, Jack Kaplan, created the philanthropic J.M. Kaplan Fund, which focuses among other things on the arts, the environment, historic preservation, and migration.

On the wall above the sofa hang several charcoal drawings by Caio, including a portrait of a friend which he painted when he and Bruno studied painting in Barcelona under Augusto Torres (the son of Gonzalo’s master, Joaquín Torres García). The lamp is made from old Chinese pottery.

How the young New York art student Betty Kaplan and the Uruguayan painter Gonzalo Fonseca met in 1955 and how they came to live in this house is a romantic story. In the beginning they shared no common language, but painting united them. She had come to Rome to study painting with the Italian artist Afro (Libio Basaldella). But he had just been offered a show in New York and he met her only to say goodbye. She sat down at the only free seat in a nearby restaurant – the next seat was occupied by tall, handsome Gonzalo Fonseca. Reader: they married.

They stayed in Rome for a while, moved to Paris and married in Tangier, then moved to Montevideo, Uruguay, where Quina was born. Elizabeth’s father bought this house as a wedding present to lure his beloved daughter home. “So sure was he of his plan,” says Isabel, “that he bought the place without my parents having seen it.”

They loved it – as who would not – and the rambling and somewhat mysterious old house became the omphalos for their life and art. As the family expanded so did the house. Floors and lofts were added in a byzantine ramble (I never did quite find my way around it). Quina, in turn, raised her children here with her then-husband, the architect Jonathan Marvel, and they added yet another floor – a new studio with a sunlit terrace looking out over the Jefferson Market clock tower. (That’s something to see – a mock minaret like something Ludwig II of Bavaria might have built if he’d decamped to New York; it is much loved and only just escaped demolition in 1958 because of a public outcry. It’s now, like this house, part of Greenwich Village Historic District.)

So now there are six floors of living space connected with big wooden stairs, steep white stairs and in one case a ladder. The huge carved head of a cherub leans out over a narrow turn in one staircase as though guarding a pair of cast-iron bunnies. There’s plenty of wit in this house.

The interior decoration of the house has also changed over the years. There were, as Isabel remembers, “period revamps, beginning in the 1950s with the stripping out of all moldings and other curly plaster fripperies. The 1970s brown mirror panels have been evicted, but the track lighting, the burlap walls and the fifty-year-old Magic Chef remain.” The magic chef really was their mother, who routinely cooked two dinners every evening because her husband liked his supper late, often in the company of other artists, many of them European or South American, and the children didn’t eat with the adults until they were older.

A striking and memorable picture of an androgynous young figure with a dog, painted by Elizabeth. Below, a drawing by Gonzalo rests against a painting on paper also by him. Both are propped against a bench freighted with kilim cushions.

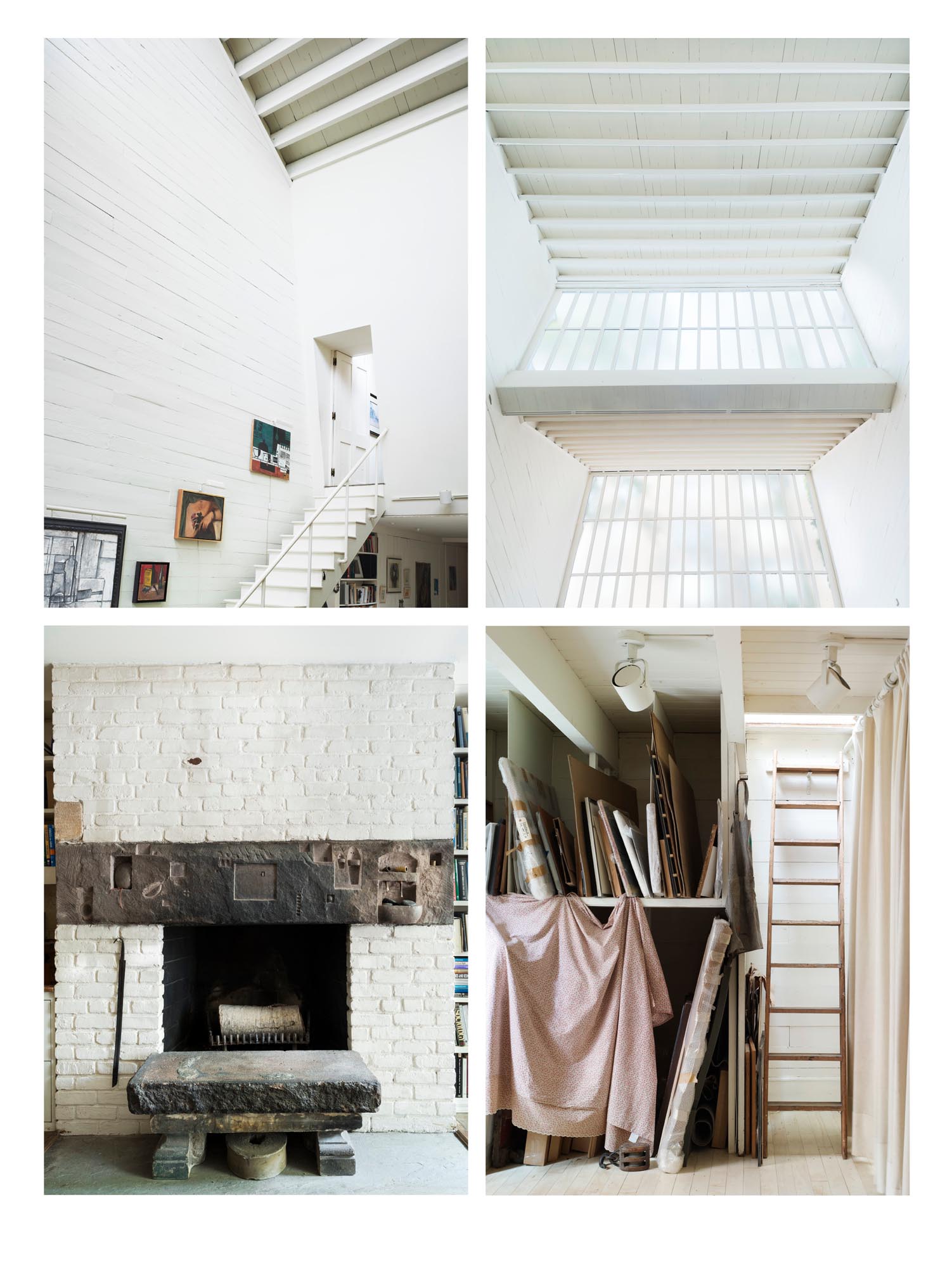

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT The revolutionary staircase, built in 1975, which joined the kitchen to the studio. The vertiginous view over the studio (which was once used as a dance studio by Rita Hayworth). A storage space for canvases beside the staircase leading to the small studio. One of the stone mantels built and carved by Gonzalo with recesses for his pipes and for placing small found objects.

A painting by Caio hangs above a desk with two further small paintings by Gonzalo. The handsome lights are early American.

A snapshot view into the myriad interests and creative activities of the Fonseca family, Many paintings by Gonzalo hang above a bookcase bearing African and Maori figures and masks, and a polished granite Egyptian torso. The bronze hand was a gift from the sculptor John Dann. The big table was made by Gonzalo from found pieces of wood, as were the small constructions on the wall and on the bookcase. On the sofa, a glimpse of a velvet appliqué cushion made by Quina for her mother.

When they ate at that big old table, if they looked towards one wall they saw a fourteenth-century Chancay burial textile sewn together to make a tapestry as touching as anything out of Cluny. (Chancay was a Pre-Columbian archaeological culture, later part of the Inca Empire.) If they looked to the other side they saw many paintings by Gonzalo and, among other fine pieces, the polished granite body of a magnificent Egyptian sculpture standing beside carved African figures. They were warmed by a fire topped by a pile of building bricks that Gonzalo made for his children.

One particular significant space was already almost immutably there – the magnificent huge white studio. Isabel describes the room as “a silent, skylit painter’s paradise soaring upward in 40-foot twin peaks, built 60 feet out on what would have been the back yard.”

Their father labored in there and Isabel describes his way of working: “His studio on the first floor was his sanctum sanctorum, a separate country in a different time zone, as it seemed to us, guarded by a forbidding sentry in a glass case behind my father’s desk in the studio’s marginally less dusty anteroom. ‘Uncle George,’ as we called him, was a mummy from Papua New Guinea with shells for eyes and an apple-size shrunken head. Unlike my own children, who wander freely into both their parents’ studies, we wouldn’t have dared pass Uncle George.”

Part of the house is dark, bookish, with the air of a reading room – and some of it is like an atelier, full of light. Every room in the house has its own particular history in the making of art, though the business of “making art” was not organized or taught. Art was just what the family did, and each one did it mostly on his or her own. They maneuvered their own way towards their art destinations, hunters and gatherers of values, bonded together in their foretime. An adolescent Bruno taught himself to draw, copying drawings by Old Masters and Cézanne; and in his room Caio also drew − mostly political cartoons for undaunted and unsuccessful submission to the New Yorker. Quina designed and made clothes on the dining table and, in her attic aerie that no one else climbed up to, Isabel wrote and illustrated stories. She is now a successful author, her works including the bestselling Bury Me Standing: the Gypsies and their Journey, about the lives of the Romany people.

When Elizabeth and Gonzalo separated and he moved out, the house changed again. She created a proper though fairly inaccessible studio of her own − a high-walled mezzanine loft at the back of the big room, reached only via a ladder and through a trap door, When in 1975 the writer and political activist Richard Cornuelle moved in, the configuration changed yet again. “It was a revelation,” Isabel says, “like our own Berlin Wall coming down, when a new stairway was built to connect the studio to the kitchen and the space was cleared for parties. But as the parties wound down and the rest of us moved out, the essential setting remained intact – every chair, object, textile and child’s lumpy clay creation secure in its appointed spot.”

Now in the light-filled reservoir of air and space that is the studio turned living room, the talent of the family is made manifest − a big wonderful yellow canvas by Caio; a striking and impressive painting, The Boy with a Column, by Bruno, done in 1981; a memorable picture of an androgynous young figure with a dog lying on the floor painted by Elizabeth. “A work of imagination,” Isabel says, “though also something of a self-portrait.”

There’s a painting by Horacio Torres, the other artist son of Joaquín Torres García. A comely stone French medieval madonna holds the Infant Jesus and both gaze down at the grand piano below them. An early American wooden articulated mannequin shows just how much the human body changes with every fashion epoch and on an easel nearby stands a big green 1961 painting by Gonzalo. On another wall hang several charcoal drawings by Caio. A kilim hangs over the high balcony studio, an old gilt French chair sits beside a junk shop find; we are in true bohemia, that much-sought-after territory, unselfconscious in its beauty, its slight disorder, its integrity and its understanding of what is serious.

But in bohemia one never knows what is going to happen next; the unexpected is part of the dream. The house has had a resurrection in a sort of reverse phoenix-like way. Quite recently there was a fire in the house in Brooklyn where Isabel, her husband, Martin Amis, and their two daughters, Fernanda and Clio, lived; and so, as Isabel says, “We have moved into the old house for the foreseeable future, restoring a waxy burnish to the floors and, we hope, lively conversation to the kitchen table. The beat goes on.”

So the house is alive again, full of family life, rising and shining.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP In the dining area, a polished granite sculpture stands near a construction piece by Gonzalo; on the wall a fourteenth-century Chancay burial textile sewn together to make a tapestry. The striking yellow exterior of the Fonseca house in Greenwich Village. A guest bedroom with the Peruvian Cuzco Madonna, dating from around 1750.