Susan Sheehan

In the entrance salon is a wonderful collection of tiles by William De Morgan; the large panel to the left of the door was part of the commission for the important Arts and Crafts mansion Debenham House in London. The grand archway and scagliola columns are original.

You’d never guess what lies behind this show-stopping brownstone with its high stoop rising to parlor level, its ornate bracketed cornice, its general eminence in a quiet street near to Union Square. I’ll tell you in a minute – but, first, a bit of its history. It was built in 1850 in a highly fashionable neighborhood – Tiffany & Co. was down here – before the tide of fashion swept on leaving it a little bit lapsed; but it’s highly fashionable again, being now in a designated Historic District – Gramercy Park. The house is full of gravitas. It was built in the Greek Revival style for the family of one Samuel Raynor, an entrepreneur who invented self-sealing and prepaid envelopes. After he died – frozen in a blizzard, and then his wife carelessly caught a chill at his funeral – the house was converted by two scrappy German architects, the Herter Brothers, to posh apartments called French flats (to distinguish them from your average tenement). In 1889 the Herters grandified and updated the facade (in fact it’s the only extant example by them), emphasized the windows with architraves and painted tin pyramidal bosses along the sides. Then for good measure they added a parapet to the cornice and made the entrance deeply imposing, with two columns flanking double entrance doors. When I first walked through these doors I felt a bit like Howard Carter, who, when he was asked on peering though darkness to Tutankhamen’s tomb, “Can you see anything?” replied with the famous words: “Yes, wonderful things.”

Perhaps a more accurate way of putting is that it’s like opening the lid of a sandalwood-scented treasure chest and coming on a palimpsest which shakes out like to magic to reveal an ideal Victorian homescape, an Aesthetic movement haven, a Moorish Spanish casa, an orientalist riad, a grand English house, a homage to the whole gorgeous liturgy of William Morris and his ilk − an audacious and successful mixture of decorative things from historic cultures put together with such good grace that they form a communion.

The first thing you see is a huge and dazzling entrance salon, Moresque to a degree, leading through a broad arch flanked with scagliola pillars topped by Corinthian capitals to other intriguing rooms; two chandeliers, one early nineteenth century, probably Irish, with Bohemian glass shades and beyond it a Pugin brass one from around 1860; a luxurious cushion-piled divan (as might have been in a seraglio), a pair of George IV giltwood chairs attributed to Morrel & Seddon (the principal suppliers of furniture and furnishings to George IV during his redecoration and regeneration of Windsor Castle in the early nineteenth century); and what you might think is an oriental screen. Talk about cultural retrieval!

The present here is suffused with the past. And the present is very present, as upstairs in a white-on-white series of rooms are prints and works on paper by artists including Vija Celmins, Willem de Kooning, Richard Diebenkorn, David Hockney, Jasper Johns, Sol LeWitt, Brice Marden, Joan Mitchell, Bruce Nauman, Richard Serra, Wayne Thiebaud, Cy Twombly and Andy Warhol.

So who is behind this miracle mixture? Step forward the owner of the house (not that she does, being modest), Susan Sheehan, founder of the eponymous gallery, which specializes in American post-war and contemporary prints and works on paper with an emphasis on minimalism and pop art.

When Susan Sheehan bought the house she knew it had gone though various manifestations over the years but that many valuable and rare details from the late nineteenth-century redecoration remained in situ. The mahogany doors, marble fireplaces, elaborate cornices with their fretwork leaf scrolls were intact and the layout – an enfilade, as it were, of three big rooms – was the same as when it was first built.

In the salon, a big and rare Queen Anne pier mirror to the side of the pillars comes from the great English country house Burley-on-the-Hill, described by a descendant as “a dignified and decorous abode, so much so, that its inhabitants are nicknamed ‘The Dismals’” – but this room is anything but dismal. It is alive, with a rich wasabi color on the walls, and it glitters with the Victorian ceramic artist William De Morgan’s tiles. She bought them from the collection of Jon Catleugh, the foremost expert on and obsessive collector of De Morgan’s work.

Susan was born in Plymouth, Massachusetts, to parents who were “visually alert and liked looking at things.” Plymouth, of course, is a place of the greatest prominence in American history, folklore and culture, and Susan learned a lot of American history both formally and by osmosis when she was growing up: she was a teenage guide for the Mayflower Society and studied American history at Barnard College, Columbia University.

She opened her own gallery in 1985 on the Upper East Side while she was still living on the third floor of a brownstone on the Upper West Side. “I thought – I love living in this brown- stone . . . I want this sort of place for my own.” New York, like Paris, is a city of quartiers and she could hardly be further away from where she first thought to buy, but as she wandered the Here-There-Be-Tygers purlieus of the Lower East Side she saw the For Sale sign outside this house. It was giant place by New York townhouse standards, about 10,000 square feet, but, undaunted, she bought it and became only the fourth owner in its long history.

It wasn’t easy going to achieve this ideal of what Jean Cocteau once said a home should be, “where the disorder from outside and the drama of the world demand a refuge.” And, while I’m on a quoting roll, Seamus Heaney once wrote about “the necessity of keeping open the imagination’s supply lines to the past.”

The beautiful wall panels are pieces of 1940s wallpaper, mounted as a multi-panelled screen, which Susan found in a flea market. Above them is the original cast plaster frieze that still has traces of the 19th-century gilding. On the cabinet are 19th-century Islamic-inspired pottery and a 16th-century Iznik tile.

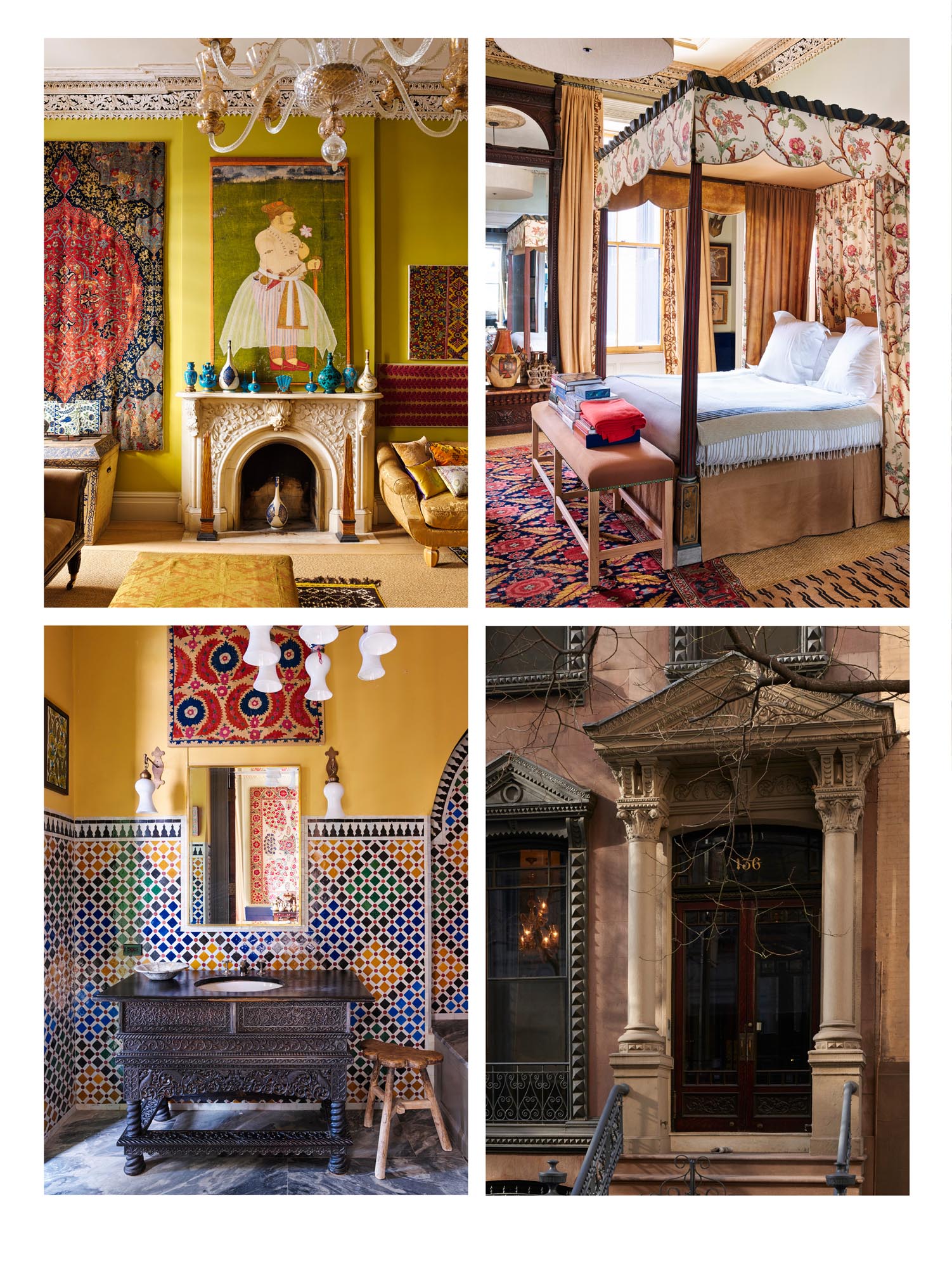

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT Above the fireplace in the salon is a c.1690 portrait from Udaipur of Maharaja Jai Singh, painted on fabric; on the left is a fragment of a center medallion 17th-century Turkish Oushak rug; on the right, a Moroccan Chechaouen silk embroidery, c.1700, above an 18th-century silk embroidered bed hanging from Crete. The Georgian four-poster bed came from Harewood House in Yorkshire and is likely to be by Chippendale; the modern hangings are by Robert Kime. The front of the house, part of its Gilded Age redecoration, is the only extant facade by the late 19th-century architects the Herter Brothers; the pyramid-shaped shaped window surrounds are cut, shaped and painted pieces of metal. The bathroom sink, made in India, is a copy of a 17th-century Indian table and, like the Alhambra-inspired bathroom tilework, was commissioned by Susan.

Talk about! Susan Sheehan has opened the supply lines full torque, and these rooms now in their conception and realization, grandeur and spaciousness, their retaining treasures, spill out the past; but they’re far from anachronistic follies – they are transformations and translations into a special visual language.

For a start the whole first floor was apartments, and on the third floor there were rent-controlled tenants who were not to be dislodged. They stayed for five years. But once they had gone she started in with unending relish on her quest and vision to restore the house and to be practical about it as well. (“We live on two of the five floors. The rest are my gallery offices and rentals.”) The “we” is she and her husband, Irish-born John O’Callaghan, now very much an American, with a worldwide custom carpet business.

Although John’s impress and input is all over the house in its practical restoration and fanatical finish, he has, in Susan’s words, “absolutely no interest in decoration.” She says, with some amusement, “Once, when a guest asked him, when we had a benefit at the house, about the De Morgan tiles he told her that I’d bought all of it in China. But he is a great cook!” There would have to be great food in a house like this, which has already roused most of the senses.

The imposing archway frames a pair of George IV giltwood armchairs, the William De Morgan tiles behind and a view through to translucent stained-glass study doors.

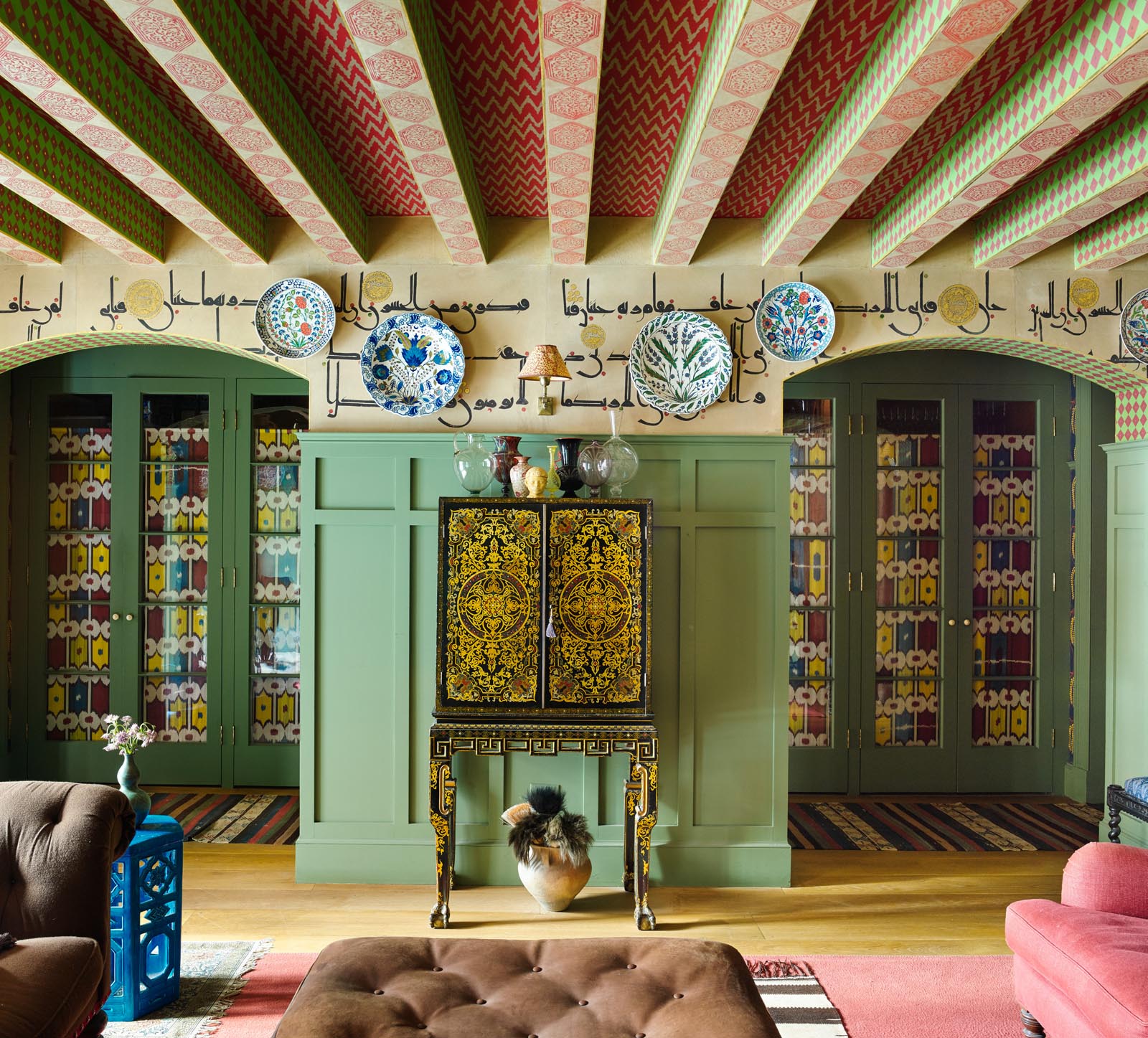

Silk ikat lines the glass fronts of cupboards in the sitting-room alcoves. Between is a 19th-century English cabinet covered with a jewel-like, polychrome, arabesque painted decoration. Above, copies of 16th-century Iznik plates are mounted on a silk-screened wall frieze modelled on a c.10th-century North African page from the Koran.

In the opening salon, its floor covered with Moroccan rugs, one looks across through an archway to an inner hall, past a central table piled with books to where beyond, through study doors with their original stained-glass panels, is a bedroom filled with light filtered through trees. But one doesn’t look ahead for long because everywhere are objects and hangings and things to catch and hold the eye. What initially looked to me like a long multi-panelled gilded oriental screen turns out to be mounted pieces of wallpaper from the 1940s, made by Gracie, the old New York wallpaper manufacturer. “They were in a grand Park Avenue dining room and when the occupant moved to smaller quarters in her dotage she took the wallpaper with her and had it mounted on screens. I bought them at a flea market.” A flea market! “Fortunately, they were an absolutely perfect fit for the space. I remember lugging them home in the back of a mini van.”

Around the walls runs a cornice and frieze looking more like lace embroidery than cast plaster and bearing traces of the original gilding. (Emilio Terry, that supreme decorator, believed that “a room without a cornice is like a man without a collar” and this is grand black tie stuff – a reproduction of the same frieze is in one of the late nineteenth-century period rooms at the Met.) The long black Chinese table is piled casually with books and treasures – a nineteenth-century blue Minton dragon vase, a black and blue glass vase by Fratelli Toso, the Venetian glassblowing dynasty, a bowl by the beloved De Morgan. Tucked underneath is an Indo-Portuguese coin collector’s cabinet in tortoiseshell veneer strung with ivory and dating from around the late seventeenth century but happy here in this timeless place. Over the original marble fireplace is a portrait on painted fabric of a portly Maharaja Jai Singh from Udaipur dating from around 1690. (A pendant piece to this is in the Victoria and Albert Museum.)

The bedroom on the first floor harbors a magnificent Chippendale bed bought from Harewood House in Yorkshire, where in the late eighteenth century Thomas Chippendale was given his biggest commission, to make furniture for the Lascelles family; the fabric for the hangings comes from Robert Kime.

Outside the windows is a paved courtyard with dining space bordered by an open loggia, its 12-foot-long divan bolstered and cushioned to within an inch of its arabesque life, evoking memories of a John Frederick Lewis painting and the wilder shores of love. There’s a continuation of that theme in her bathroom (once the butler’s pantry, as she realized when she discovered a stove behind the wall), inspired by the bath complex at the Alhambra: “I knew a shop in New York that made tiles in Fez and asked them to copy an illustration. Which they did. Perfectly. The sink made in India by Frozen-Music is a copy of a seventeenth-century Indian table that I saw in Amin Jaffer’s book about Indian furniture.” (Who better to provide inspiration? Dr. Jaffer is International Director of Asian Art at Christie’s.)

The tiles around the fireplace and the wall-mounted plates are by William De Morgan. The vase on top of the 17th-century shagreen-covered English cabinet is by Ulisse Cantagalli, as is the lusterware pot on the mantelpiece. The handsome blue pitcher is American Southern Pottery.

She is witchily good at having friends, and finding people who do what she asks in decorative terms, no matter how esoteric it may be. For example, in the downstairs sitting room some beautiful calligraphy ornaments the walls. “I saw this Koran page in a Sotheby’s auction catalogue many years ago and saved the image. It’s North African, probably ninth or tenth century.” It was silkscreened on to tea-stained Japan paper by her friends Dan and Sue, who turn out to be the brilliant decorative painters Dan Sevigny and Sue Bachemin of SB Studios. And on the walls in the sitting room downstairs are what look like sixteenth-century Iznik plates. “I originally wanted to buy period plates. I did the math on the cost to complete the frieze and had second thoughts. So I found an artist in Istanbul who made very good copies of Iznik ware, bought a book that illustrated all of the most beautiful period Iznik plates extant, mostly in museums, and sent him pictures. He copied them with great accuracy.”

The sitting room has Arts and Crafts panelling and big glass-fronted cupboards with their covetable contents, many and varied, hidden by stretched silk ikat from Uzbekistan that Susan bought in the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul. The ceiling, with its many beams, is covered in hand-screened wallpaper in an inspired combination of designs from beams in Ottoman and Middle Eastern houses and a Koran binding that she spotted in a museum collection. This ceiling tour de force is again by the Dan Sevigny and Sue Bachemin SB Studios combo, who seem to be able to turn their hand to anything. Their greatest coup d’œil in the house is the screen-printing on Japan paper on the walls of a small room downstairs. “It’s a copy of one of the great treasures of early fourteenth-century textile art: the panels were once part of a tent made during the Mongol period, in either China or the eastern Islamic area, and used on military campaigns,” Susan explains. “The original is a lampas-woven textile of silk, gilded paper, and gilded animal substrate. Some panels are now in the David Collection in Copenhagen, others in the Museum of Islamic Art in Qatar – and we have screen-printed copies right here on 16th Street in Manhattan!”

It’s obsessive and it’s magnificent. And magical.

Late 19th-century Tibetan tiger rugs, which Susan collects, are laid on 19th-century Spanish floor tiles and hang on the screen-printed Japan-papered walls of the little sitting room. The Edo period Japanese hanging light is made of intricately pierced and chased bronze in a peony arabesque design.