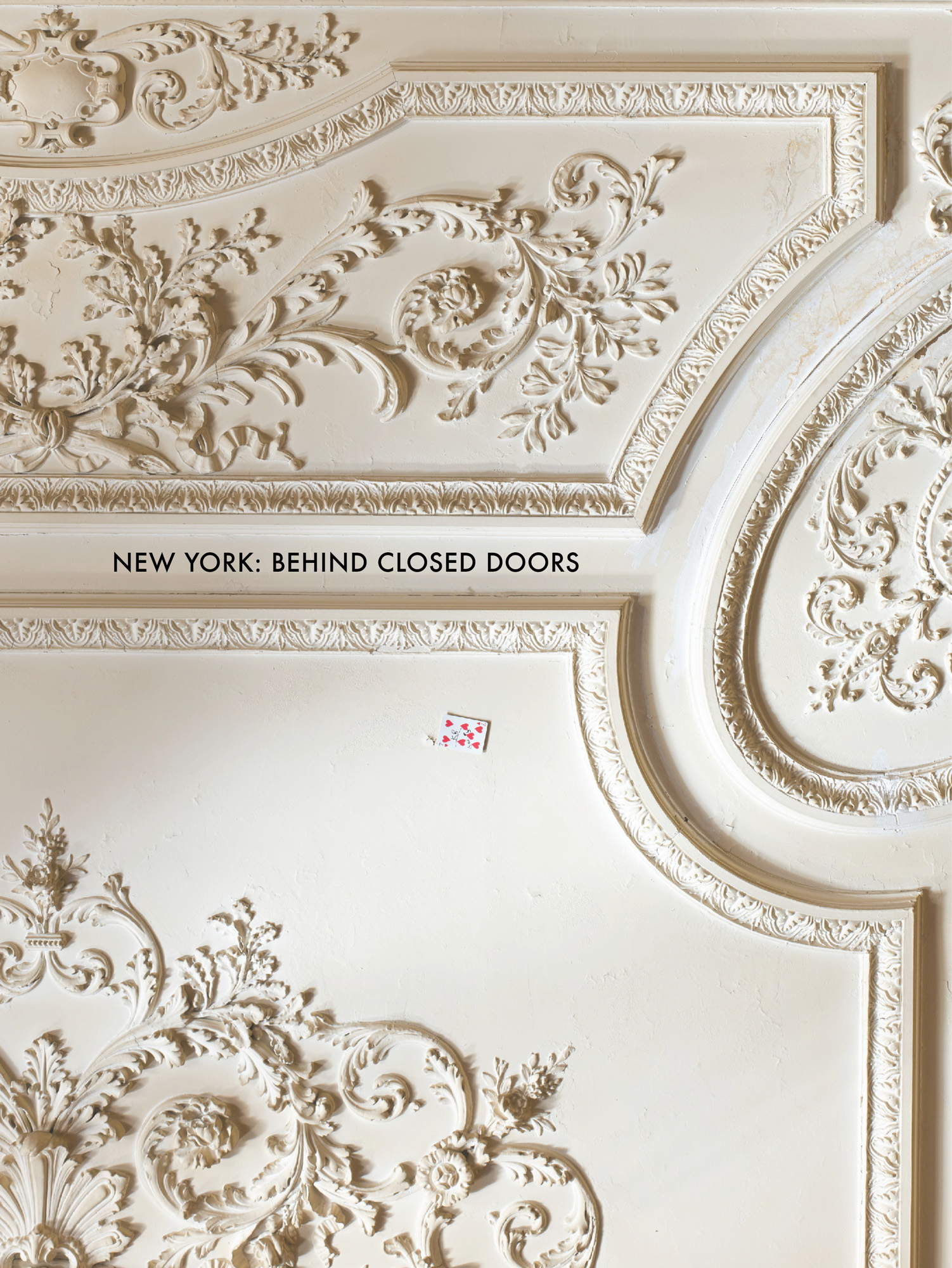

Kenneth Jay Lane’s apartment in Murray Hill: the salon ceiling, with a playing card spun up there by a magician many years ago.

Ugo Rondinone’s bed, Red Riding Hood and the Wolf, by Verne Dawson.

A wall in the Fonseca family house in Greenwich Village

This book is called Places to Write Home About because my only criterion for choosing these apartments, lofts, studios and houses is that I like them so much I want to tell other people about them. They are fired by imagination and created by people who refuse to live in a narrowly functional world; they know that creativity and imagination are essential to our lives.

There is something else. The most important future source of historical information about how some people live in New York today is in books like this and certain magazines. In 1848, the great English historian Lord Macaulay wrote, “Readers who take an interest in the progress of civilization and of the useful arts . . . will perhaps wish that historians of far higher pretensions had sometimes spared a few pages from military evolutions and political intrigues, for the purpose of letting us know how the parlors and bedchambers of our ancestors looked.”

So here we are, with no pretensions, in the parlors and bedchambers of artists and writers and garden designers, jewellers and professional decorators, photographers and art dealers, architects and fashion editors – in short, the ordinary people of New York – in different niches of the city, who opened up their domestic arrangements to show their ways of living – idiosyncratic, curated, aesthetic, unique, and also spontaneous, unrehearsed and everyday. Their places are never just stationary backdrops – they are provocative presences that elicit interaction, conjured up by people who know that living gracefully does not require attempting the impossible,

In doing this I am merely following in the footsteps of great observers and writers: Mario Praz’s masterly An Illustrated History of Interior Decoration, published in London in 1964, was both a love letter and a breakthrough in arousing interest in the art of interior decoration. Peter Thornton’s Authentic Decor: The Domestic Interior 1620−1920 (1984) and Charlotte Gere’s Nineteenth-Century Decoration: Art of The Interior (1989) were seminal. And, of course, the alluring magazine The World of Interiors, which first appeared in 1981, was a revelation to many − though, I have to say, my own reaction on seeing it was, “Well! About time too.”

Because I grew up in 1950s Northern Ireland, where the decorating ethic in all its fine completeness was Kitchens is Buff and Landings is Brown, where the concept of collecting meant the saving of small pieces of string and brown paper, and where beauty was grimly regarded as an Occasion of Sin, I craved ornament. In The Merchant of Venice, that passionate play about the weights and measures of the heart, Bassanio sighs, “The world is still deceived by ornament . . . the guiled shore To a most dangerous sea.” Indeed, indeed, and I hoisted my sail and set out on that sea years and years ago and have now lost sight of the shore. But I don’t think I’ve been deceived. I’ve been delighted and enchanted.

All my adult life I have contrived to live in houses which, crammed with the fruits of my collecting addiction, I think and hope are beautiful – if somewhat disconcerting to any minimalist – and I have always been obsessive about looking at interiors all over the world, and sometimes writing about them. I hold that making your own environment beautiful is as valid a work of art as any piece of writing, or painting or sculpture; we should approach decoration in the way that we approach the other arts. Yet the handiwork, taste, inspiration and labor that goes into composing a pretty room is too often regarded as happenstance. Women have done it throughout the centuries. Edith Wharton wrote about this; she thought of houses and environments as provocative presences and wrote of how decorating her houses and the creativity involved was essential to her, an act of self-definition, a way of finding her voice. (She was a dab hand at description. “The drawing room walls, above their wainscoting of highly varnished mahogany, were hung with salmon-pink damask and adorned with oval portraits of Marie Antoinette and the Princesse de Lamballe. In the center of the florid carpet a gilt table with a top of Mexican onyx sustained a palm in a gilt basket tied with a pink bow. But for this ornament, and a copy of The Hound of the Baskervilles which lay beside it, the room showed no traces of human use.”)

In this album, I have shown telling examples of the different styles and different ways of living in this tremendous series of towns called New York, a tumbling ziggurat spilling exuberantly across its parks and rivers and neighborhoods. Within the five boroughs are more quartiers and arrondissements than in Paris and more markets and bazaars than in Cairo. There’s an infinite diversity of architectural styles and buildings to be seen literally on every side. The inescapable Beaux Arts style, the many monuments by McKim, Mead & White, the white brick 1960s behemoth apartment blocks towering above modest brownstone houses; French gothic chateaux, Italian Renaissance palazzi, sham Louis XVI furbelowed facades flaunt themselves next to restrained Georgian-style town houses; baroque-faced churches, prim Puritan places of worship, elaborate synagogues are jumbled next to turreted fantasies, vast apartment blocks, gleaming mirrored office skyscrapers. It’s all utterly New Yorkian. And if, in the great canyons of Manhattan, you look skywards, follies and ornamentation add whimsy to the top of plain-faced buildings, and gardens akin to the fabled Babylonian greenery bloom on the flat roofs of apartment blocks. And, of course, everywhere in Manhattan are those essential icons of the city the water towers − surprisingly vestigial-looking and old-fashioned, and adding greatly to the skyscape.

But looking at New York from the outside gives no clue to its interiors. In The Decoration of Houses, those two didactic experts Edith Wharton and architect Ogden Codman Jr insisted that it must never be forgotten that good decoration is interior architecture; but it’s an evanescent architecture, and a beautiful interior is so ephemeral, so easily lost, a visual moment gone for ever. Even in families who have lived in houses for generations, the decoration and taste of one era, however inspired, is usually changed, sometimes despised by the next. (I remember at auction a gilded bureau inlaid with mother-of-pearl and tortoiseshell by Boulle, the great French court cabinetmaker of the seventeenth century. Surely no one who saw it could fail to be bowled over by its exquisite if overwrought beauty. Yet it had lain in a dusty attic for over a hundred years. It sold in 1988 for £1.2 million.) Given the perpetual work-in-progress and ruthless remaking of New York, where so little is permanent or revered, the restoration of the Payne Whitney house (now the offices of the Cultural Services of the French Embassy) on Fifth Avenue is an almost-miracle.

In writing about contemporary decoration, trying to grasp the essence of a current period is important. And almost impossible. In Authentic Decor Peter Thornton wrote, “What characterizes a period in the field of interior decoration is the density of pattern and arrangement that prevails at the time.” But there is no discernible inclusive density of pattern and arrangement in my chosen places. Some are penny plain and some are tupenny colored. Some are the homes of architects. Linda Pollak and Sandro Marpillero transformed a nineteenth-century shoe factory into a live-work loft. Bastien Halard was his own architect in recovering their house from dingy apartments to the clarity it has now. Others have used architects to orchestrate their ideas and plans: the architect Sam White, great-grandson of Stanford White of McKim, Mead & White, played a major role in the early stages of restoring James Fenton’s Harlem house; Gordon VeneKlasen had the architect Annabelle Selldorf design the major turnaround in his mews house. Some are the homes of decorators, and others have used decorators. But all are in essence the creation of their owners.

Many of the owners – writers, poets, artists, creators, and image bandits – are collectors; not one is a passive consumer. Collecting is a problematic subject. It’s often deciphered as being related to a stifled creative urge, and one plausible theory is that collecting is not only an instrument designed to allay a basic need but also an escape hatch for feelings of danger and the re-experience of loss. Yet, for all the evidence of a collecting habit, nothing seems perceptibly stifled about these rooms full of idiosyncrasies and comfort in every sense; certainly, they reveal the affection the owners have for objects and paintings and their careful placement often results in a witty piece of domestic theater.

The arrangements in many of these rooms show the intuitive and exacting discipline these collectors bring to bear on their habit. Saul Bellow said that culture means having access to your own soul and these rooms are full of culture and soul (though none, praise be, are soulful: they may be conceived as a mirror of the spirit but there’s a fair bit of irony scattered around). As Vogue scolded in a 1925 article on decoration: “We shall find any interior that does not flow from our own instincts a cold unconvincing background for ourselves.”

Sometimes when writing about the owners and their rooms my mind strayed to the habits of the bowerbird, that great master of delightful, transient installation in the natural world. He – yes, he – constructs elaborate bowers and tunnels adorned with pebbles, feathers, shells, bits of glass, “not as nests,” the dictionary says, “but as places of resort.” (But then again, the bowerbird is among the most behaviorally complex of bird species.)

As we see, so we are – that is a grade of human character, connected to the quality of perception of the external world. William Morris’s famous and kindly advice holds as true today as when he issued it nearly 150 years ago: “If you want a golden rule that will fit everything, this is it: Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.”

I’m chary of pronouncing on questions of taste – one person’s taste is often another’s opportunity for eye-rolling – but I’m not chary of pronouncing on what makes a house a beautiful place to live in and to be looked at, regardless of size, period or proportions. Such houses contain spaces that are rational and are full of personal vision, often calm, with the power to affect feelings.

Being in these places can lighten the heart – and, what’s more, looking around them is an educative process. Some here are a brilliant curation of the art of the twentieth and the twenty-first centuries; another has examples of work from the American Arts and Crafts epoch; here is early Peruvian religious imagery; and there is a rare example of the art of the Mound Builders, one of the vanished cultures of North America. All are lessons to the eye.

There’s a touching and cringe-making sequence in Swann’s Way concerning Odette, the beautiful, sly and stupid courtesan who professes to be deeply interested in furniture. Swann, one of Proust’s saddest and most lovable characters, a gentleman, elegant, intellectual, with refined taste (and enormously rich) allows himself to be debased by his obsessive love for her. When he mildly criticizes her friend for buying a job lot of pretentious sham-antique furniture, she blurts out to Swann what she really thinks of his own (exquisite, understated) house: “You wouldn’t have her live like you, among a lot of broken-down chairs and threadbare carpets!”

There’s no sham among these things here, and there are some threadbare carpets. And I warrant Odette wouldn’t have been overly keen on Kenneth Lane’s dishtowel cushions or Jane Rosenblum’s anaglyptic staircase.

The way we arrange our house interiors is an advertisement for our interior life. Emotional disharmony makes for disturbing and untidy and even slovenly environments; and places have profound effects on well-being, and style and taste are like perfect manners.

On this showing New York is full of balanced, wise, deeply clean, perceptive and enchanting people, who use their personality traits and imagination to the fullest. The one thing all these paragons share is that they love their home town with a passion. John Updike summed it up: “The true New Yorker secretly believes that people living anywhere else have to be, in some sense, kidding.”

So, these are letters about places of resort to write home about, to the misguided people who live elsewhere; and, of course, they are love letters.

In the living room of Barbara Jakobson’s house on the Upper East Side, the ghost of the Frank Stella wall relief Felsztyn III looms over Jeff Koons’s Winter Bears and the curving “Non-Stop” sofa.

Timothy Van Dam and Ron Wagner’s Orientalist Library in Harlem.

Matelots, windswept maidens, shells and patterns in rich purples, reds and yellows frolic over a 1936 verre églomisé cabinet. It comes from the Helena Rubinstein estate and now is in Amy Fine Collins’s Upper East Side dining room.