Donald & Patricia Oresman

Some apartments in New York are startling on first impact. One such stunner is in a duplex in the Gainsborough Studios, a Landmark slender building erected in 1908 to the design of Charles W. Buckham on Central Park South near Columbus Circle, which has been beautifully restored with its facade of vivid geometric tiles and Gothic-style window screens. It speaks of a different world from the brazen bleak brass and black Trump tower nearby.

So. Once inside the cast-iron door you’re in a foyer with Arts and Crafts charm, warm red polished tiles on the floor, an eccentric elevator. The building was commissioned by a group of artists to provide comfortable artistic quarters − 18-foot-high studios and double-height windows to let in the northern light. Those windows have a magnificent view looking due north over Central Park and on a sunny day it looks like Utopia out there. But then again everything up here is fairly wonderlandish.

The elevator doors open, you pass through an ordinary door and you achieve metaphoric lift. I wouldn’t be surprised if I’d tumbled down a hole into this little conceit, a pied-à-terre fitted out as a Renaissance-style library of polished French maple wood, compact, detailed, with pediment-topped and pilaster-detailed bookcases, a coffered ceiling and a mezzanine-level gallery. It’s a retreat for living and reading and dreaming where physical details and metaphysical ideas interact in an enclosed world and it’s the achieved dream space of a successful and formidable man, one who couldn’t have looked and behaved in a more ordinary and more businesslike way. His name was Donald Oresman and for years he was a highly successful attorney, general counsel of Paramount Communications and member of the board of more philanthropic organizations than one would care to count. He was also a visionary, a committed conservationist (chairman of New York Landmarks Conservancy), and he was passionate about the arts and especially about literature. Reading was his pleasure and escape and he felt as one with George Steiner – whom he often quoted – about the profoundly solitary and fierce privacy in the act of reading.

Donald Oresman also loved looking at things. He shared both these pursuits with his wife, Patricia, another avid reader, whom he had married in 1948 (“the smartest decision of my life”). Together they began to amass their treasury of books and later to buy twentieth-century images – with this twist: every single one, from everywhere and in all styles in every conceivable medium, oil paintings, prints, drawings, photographs, watercolors, acrylics, needlepoint, painted leather, gouaches and ceramics; sculptures, in bronze, cast iron, balsa wood, in marble, in stone, in wood, papier mâché, glass, scrap metal and polyadam (a delightful pair of bookends by Tom Otterness) – all had to be on subject of people in the act of reading. He was relentless in his pursuit. “There’s a bit of the Captain Ahab about me,” he admitted cheerily.

Elegantly carved maple wood creates stairs, galleries, bookshelves and a series of enticing reading spaces around a central light-filled sitting area. The angled oil painting behind the sofa is Counting Sheep by Katherine Freeman.

This double-height library was designed to house at least two thousand books –mostly literary criticism, contemporary fiction and poetry – and much the same number of works of art. But the art collection was forever expanding. “I think I built it too small,” he mourned, but he knew there had to be a limit. Not that he ever reached it.

The collection is 95 per cent North American or European; the rest is from South America and Japan. He had his favorite eras, the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, and he particularly liked the work of the early twentieth-century Ashcan School. It’s a catholic assemblage and now includes – let’s do this alphabetically and geographically – examples by Balthus, Aubrey Beardsley, Max Beerbohm, Vanessa Bell, Chagall, Cocteau, Roger Fry, Alberto Giacometti, Eric Gill, Duncan Grant, Gwen John, Fernand Léger, Magritte, Matisse, Henry Moore, Picasso and Diego Rivera; American artists include Thomas Hart Benton, Abe Blashko, Elizabeth Catlett, Richard Diebenkorn, Jim Dine, Doris Lee, Reginald Marsh, Larry Rivers, David Smith, Tabitha Vevers and Andy Warhol.

Everything here has strength of personality or presence; it’s been scrutinized before being allowed in. Oresman was somewhat dismissive of photographs. “They have to be fairly adventurous to interest me,” he said. “Otherwise they’re verging on journalism.” (Paradoxically, Robert Henri, the leader of that ragbag company of New York artists the Ashcan School, specifically wanted art to be akin to journalism.) Nevertheless, Oresman owned photographs by such great names as Berenice Abbott, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Frank. But au fond he didn’t care about names – it was how the artist viewed the subject. “There is an intensity to reading that captures artists’ imaginations,” he said, “a very private element to it.”

It all started when he and his wife bought a 1973 lithograph by Jim Dine called Nancy Reading, published by the remarkable Petersburg Press. A few weeks later they bought a drawing by Larry Rivers of the poet Frank O’Hara, nose in a book, and that was that. In the face of the evidence piled around him, the vast accumulation, he was happily adamant that he wasn’t a collector and indeed was bemused as to why I burst into laughter. “I’m orderly,” he protested, “so we decided we would concentrate on one area.” “Have it your own way, Donald,” I said in familiar fashion, “but you’re a dyed-in-the-wool, hard-core, chronic, incorruptible collector.” He had the grace to laugh, but continued in full-scale denial. “I am not a collector and I am not interested in books as objects.” We left it at that.

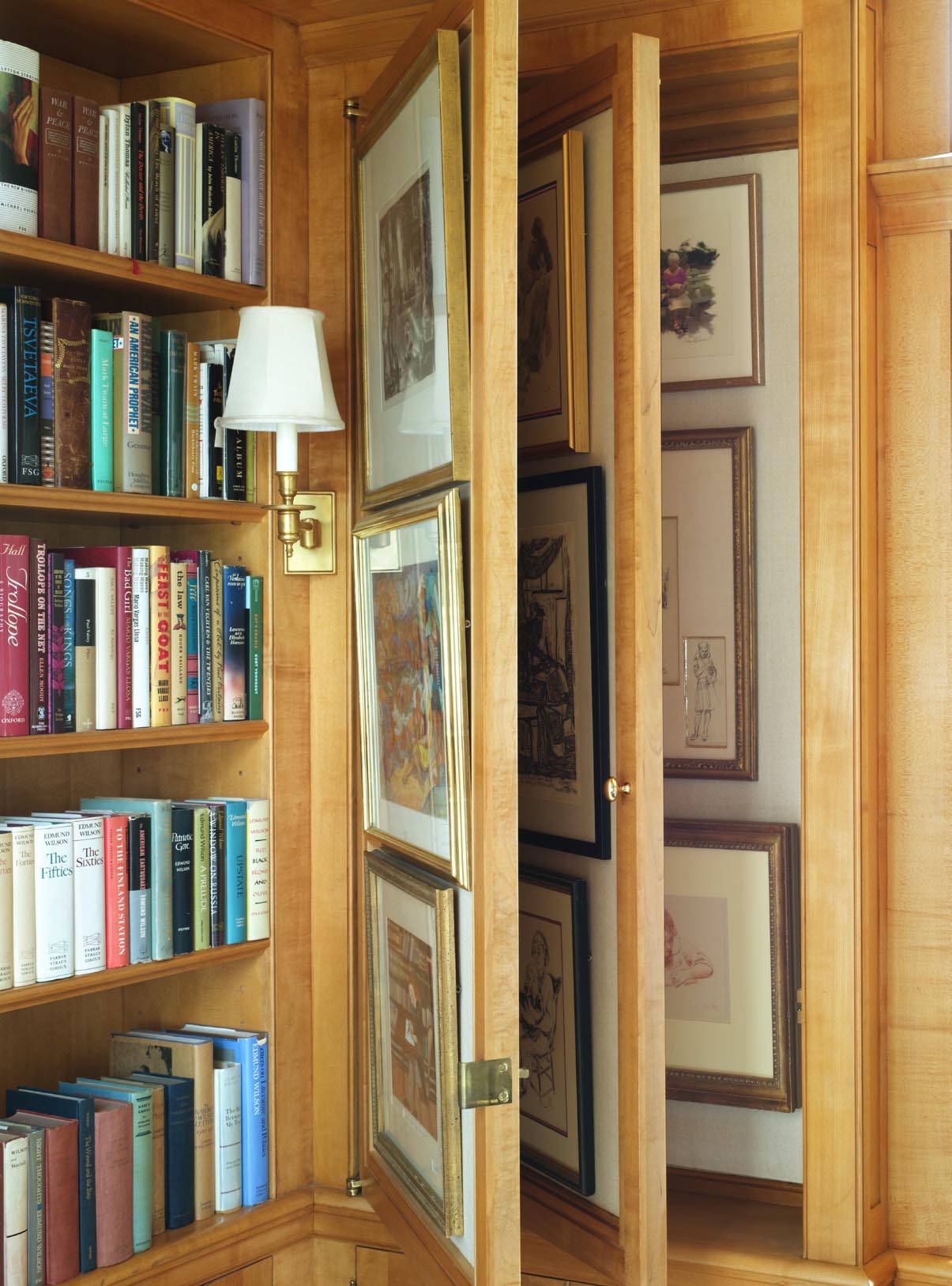

“I have a clerical mind,” he said, “and I follow a rigorous policy. If I buy something framed, I hang it on the wall, and if I buy something unframed I stick it under the bed.” Well, I suppose under the bed is one way of describing the meticulously designed maze of drawers filled with drawings pleated into every available inch of the library. Other works are stored in complex double and triple layered sets of intricately constructed sliding and hinged panels that swing open to reveal pictures on pictures – like the Hogarthian sets in Sir John Soane’s Museum in London.

Huge north-facing windows look out across Central Park. Mounted on the pedimented mirror is Michael Hurson’s Study for Man Reading Newspaper; among the paintings lined up on the floor are Woman and Literature – Medina and Gillian, by Claire Khalil, and The Deaf Man Heard the Dumb Man Say That the Blind Man Saw the Lame Man, by Michael Lenson.

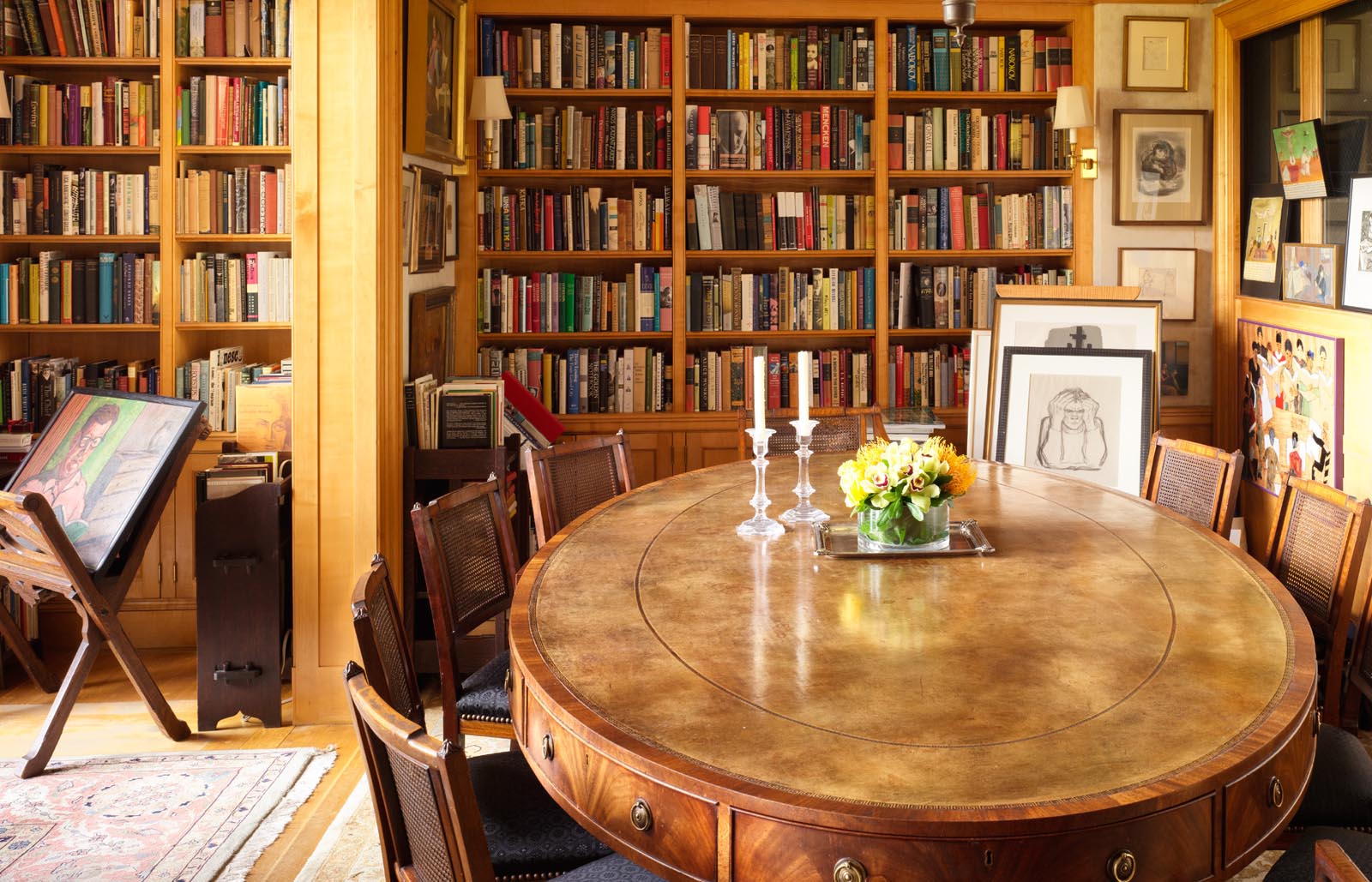

The library accommodates a charming dining area. The mahogany and leather table is a reproduction of a Victorian one Donald Oresman liked.

He knew exactly what he wanted when he commissioned the interior design of the apartment in 1996. He gave free rein to his architect, Richard Sammons of Fairfax & Sammons, with one proviso. “I told I him didn’t want it to be dark wood – mahogany, heavy – I wanted it to be light and airy and it needed to be practical and comfortable because I wanted to live here too during the week, to eat, sleep – and read.” (In the country house in Larchmont he had over ten thousand books and there is an Oresman Gallery in the local library.)

So this library doubles discreetly as a living room with a fireplace and a dining room, and behind a door at the back, a bedroom and a bathroom.

When he bought the apartment it had white walls and many mirrors; the big window with its architrave filling the north wall was already there. “The place was awful,” the architect remembered, “like a racquetball court.” It took about nine months to remodel it and the result is this light-filled confection with a series of bookcases projecting out at right angles, making shadowy reading spaces within each bay. The gleaming surfaces are carefully articulated, and the shelves have pediment facades modelled on ancient tabernacles where scrolls were kept. The fireplace in the central bay has a trompe l’œil timber chimneypiece painted black to resemble marble, and on its hearthstone Samuel Beckett’s famous mantra “Try again, Fail again, Fail better” was carved by the English master carver Simon Verity. Above this level is the curved mezzanine gallery housing more books and pictures and the balustraded bed space balcony flanked by bowed mirrored cupboard doors giving different views and perspectives. It’s reached by a precipitous spiral staircase, based on the helix-shaped one in the Loretto Chapel in Santa Fe, known as the Miraculous Stair.

Every year at Christmas Donald Oresman and his wife sent their friends a delicious little bon-bon of a book privately printed and usually illustrated by his great friend Brendan Gill of the New Yorker. The cover always had an apt and often erudite aphorism or quote about reading: “I have gathered a posy of other men’s flowers and nothing is mine but the cord that binds them” – Michel de Montaigne; “Everything in the world exists to end up in a book” – Stéphane Mallarmé. They have become collector’s items.

Donald and Patricia Oresman had probably the world’s largest collection of art organized around the theme of the reader; and they were generous in loaning works to museums. When Donald Oresman died in 2016, he left behind a unique monument to literature and to himself. Wordsworth’s words could be his epitaph.

Dreams, books are each a world: And books we know,

Are a substantial world, both pure and good.

Round these, with tendrils strong as flesh and blood

Our pastime and our happiness will grow.

Ingenious hidden storage is beautifully crafted, and no corner is unused.

Unframed prints are kept in sliding shelves (left), while others, framed, are displayed on a series of openable panels (right) based on the secret hinged panels in Sir John Soane’s Museum.

The fireplace, with its trompe l’œil painted marble surround, has Beckett’s “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” inscribed on the hearth by letter-carver Simon Verity. On the wall of the gallery above is Donald Baechler’s Profile with Child Reading. In the alcove to the left is a Picasso lithograph, Jacqueline Lisant.