Stato da Mar

1381–1425

Venice had been taken to the limit by the slogging contest in its own lagoon. For two years all trade ceased. The fleet was ruined, the treasury emptied; naval supremacy of the Adriatic was formally gifted away to Hungary in the treaty of 1381. The Genoese wars, plague, Cretan rebellion and papal trade bans had made the fourteenth century a testing time. Yet the Republic had survived. And in the wake of Chioggia the city was able to stage an extraordinary recovery. In the half-century after 1381, the Stato da Mar underwent a burst of colonial expansion that would carry the Republic to the height of maritime prosperity and imperial power. Venice returned to astonish the world.

On the turn of the fifteenth century the eastern Mediterranean was a mosaic of small states and competing interests. The Byzantine Empire continued to decline; the kings of Hungary were losing their grip on the Balkans; the Ottomans were pushing west in their place; the opportunist Catalans, who had been a scourge of the eastern sea, were starting to withdraw. Elsewhere Genoa, Pisa, Florence and Naples, along with an assortment of adventurers and freebooters, held a string of islands, ports and forts. As Hungary’s hold on the Adriatic weakened and the Ottomans drew ever nearer, many of the small cities on the Dalmatian coast that had once struggled so hard against Venice came to seek its protection. When the Ottomans in their turn were thrown into turmoil by civil war, the Republic prospered. Between 1380 and 1420 Venice doubled its land holdings – and almost as importantly its population. Many of these acquisitions were in mainland Italy, but it was the strengthening of its maritime empire that enabled Venice to cement its position as the dominant power in the sea and the axis of world trade.

The methods it used to annex new possessions were highly flexible: a mixture of patient diplomacy and short sharp applications of military force. Where the city had obtained an empire by job lot after 1204, these new acquisitions were piecemeal. Ambassadors were despatched to guarantee the safety of a Greek port or a Dalmatian island; an absentee landlord could be tempted to sell up for ready cash; a couple of armed galleys might persuade an embattled Catalan adventurer it was time to go home or swing a factional dispute in a Croatian port; a wavering Venetian heiress might be ‘encouraged’ to marry a suitable Venetian lord or to bestow her inheritance directly on the Republic. If its techniques were patient and variable, the Republic’s underlying policy was frighteningly consistent: to obtain, at the lowest cost, desirable forts, ports and defensive zones for the honour and profit of the city. ‘Our agenda in the maritime parts’, the senate declared in 1441 like a corporation setting out its strategic plan, ‘considers our state and the conservation of our city and commerce.’

Sometimes cities submitted to Venice voluntarily to avoid unwelcome pressures from the Ottomans or Genoese. In each case Venice ran the slide rule of cost–benefit analysis over the application, like merchants eyeing the goods. Did the city have a secure harbour? Good water sources for provisioning ships? An agricultural hinterland? A compliant population? What were its defences like? Did it control a strategic strait? And negatively, what would be the loss if it fell to a hostile power? Cattaro, on the Dalmatian coast, made six requests to submit before the Republic agreed. Patras applied seven times. On each occasion the senators listened gravely and shook their heads. When it came to outright purchase they waited for the stock to fall. Ladislas of Hungary offered his claim to Dalmatia in 1408 for three hundred thousand florins. The following year, with his cities in revolt, Venice sealed it for one hundred thousand. And sometimes the choice was money or compulsion; the carrot and the stick were applied in equal measure. By patience, bargaining, intimidation and outright force, Venice extended the Stato da Mar.

One by one the red-roofed ports, green islands and miniature cities of Dalmatia and the Albanian coast dropped, almost effortlessly, into its hands: Sebenico and Brazza, Trau and Spalato, the islands of Lesina and Curzola, famous for shipbuilding and sailors, ‘as bright and clean as a beautiful jewel’. The key to the whole system was Zara, over which Venice had struggled to maintain its dominance for four hundred years. Now it submitted to Venice by free will, with cries of ‘Long live St Mark!’ To be quite certain, its troublesome noble families were moved to Venice, then offered positions in other cities along the coast. Once again the doge could style himself lord of Dalmatia. Only Ragusa, proudly independent, escaped permanently the embrace of St Mark.

The value of this coast was inestimable. Venetian galley fleets could thread their way up the sheltered channels of its coast; protected by its chain of islands from the Adriatic’s unpredictable winds – the sirocco, the bora and the maestrale – they could put in at its secure harbours. The Republic’s ships would be built from Dalmatian pine and rowed or sailed by Dalmatian crews. Manpower was as important as wood, and the maritime skills of the eastern shore of the Adriatic would be at the disposal of Venice for as long as the Republic lasted.

If Zara was important, the acquisition of Corfu was more so. They bought the island from the king of Naples in 1386 for thirty thousand ducats and with the ready acceptance of its populace, ‘considering the tempest of the times and the instability of human affairs’. Corfu was the missing link in a chain of bases. The island – which Villehardouin had found ‘very rich and plenteous’ when the crusaders stopped there in 1203 – occupied an emotional place in the city’s history. Here the Venetians had lost thousands of men in sea battles against the Normans in the eleventh century; they were gifted it in 1204, held it briefly, then lost it again. Its position, guarding the mouth of the Adriatic, also provided critical oversight of the east–west traffic between Italy and Greece. Across the straits, Venice acquired the Albanian port of Durazzo, rich in running water and green forests, and Butrinto just ten miles away. This triangle of bases controlled the Albanian coast and the seaway to Venice.

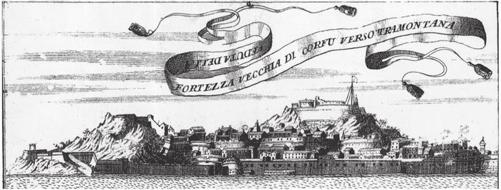

The fortress of Corfu

Corfu itself, verdant, mountainous, watered by the winter rains, became the command centre of Venice’s naval system and its choice posting. They called it ‘Our Door’ and stationed a permanent galley fleet in its secure port under the captain of the Gulf; in times of danger his authority would be trumped by the all-powerful captain of the sea, whose arrival was announced with belligerent banners and the blare of trumpets. All passing Venetian ships were mandated to make a four-hour stopover at Corfu to exchange news. They came gladly, seeing the outline of the great island floating up out of the calm sea, like a first apprehension of Venice itself. Corfu provided fresh water and the delights of port. The prostitutes of the town were renowned, both for their favours and the ‘French disease’; and sailors on the homeward run, being pious as well as frail, also stopped further up the coast at the shrine of Our Lady of Kassiopi to give thanks for the voyage.

The Ionian islands south from Corfu were added in this new wave of empire: verdant Santa Maura, craggy Kefallonia, and ‘Zante, fior di Levante’ (Flower of the Levant) in the Italian rhyme. Lepanto, a strategic port tucked into the Gulf of Corinth and potentially attractive to the Ottomans, was taken by despatching the captain of the Gulf with five galleys and emphatic orders to storm or buy the place. Faced with the choice of decapitation or a safe conduct and 1,500 ducats a year, its Albanian lord went quietly.

The gold rush of new acquisitions stretched round the entire coast of Greece. Zonchio, a well-protected harbour close to Modon, was bought in 1414; Naplion and Argos in the Gulf of Argos came by bribery; Salonica begged for protection from the Turks in 1423. Shrewd in their moves and cognisant of their manpower shortages, untempted by feudal ambition and landed titles in a landscape that yielded so little, the senate refused the submission of inland Attica. What mattered and only mattered was the sea.

Further south, the barren islands of the Cyclades, offered to Venetian privateers after 1204, had become an increasing problem. The Republic had repeated difficulties with their overlords, by turns treacherous, tyrannical, even mad. Turkish, Genoese and Catalan pirates also plundered the islands, abducted their populations and rendered the sea lanes unsafe. As early as 1326, a chronicler wrote that ‘the Turks specially infest these islands … and if help is not forthcoming they will be lost’. The Florentine priest Buondelmonti spent four years in the Aegean in the early 1400s and travelled ‘in fear and great anxiety’. He found the islands wretched beyond belief. Naxos and Siphnos lacked any sizeable male population; Seriphos, he declared, offered ‘nothing but calamity’, where the people ‘lived like brutes’. On Ios the whole population retreated into the castle each night for fear of raiders. The people of Tinos tried to abandon their island altogether. The Aegean looked to the Republic for protection, ‘seeing that no lordship under heaven is so just and good as that of Venice’. The Republic started to reabsorb these islands, but as ever its approach was fiercely pragmatic.

*

The empire that Venice acquired in this second wave of colonial expansion was held together by muscular sea power. To its triangle of priceless keystones – Modon–Coron, Crete and Negroponte – was now added Corfu. But beyond, the Stato da Mar was a shifting, supple matrix of interchanging locations, flexible as a steel net. The Venetians lived permanently with impermanence and many of their possessions came and went, like the moods of the sea. At one time or another they occupied a hundred sites in continental Greece; most of the Aegean islands passed through their hands. Some slipped from their grasp only to be regathered. Others were quite ephemeral. They held the rock of Monemvasia, shaped like a miniature Gibraltar, on and off for over a century and they were in and out of Athens. They had a foothold there in the 1390s, when they watched Spanish adventurers stripping the silver plates from the Parthenon doors, then ruled it themselves for six years. Fifty years later they were offered it again, but by then it was too late.

Nowhere exemplified reversals of colonial fortune as sharply as Tana, on the northern shores of the Black Sea. After Venice was ousted by the Mongols in 1348, a merchant settlement was restored in 1350 and maintained for half a century. But Tana was so far away that news was slow to reach the centre. The galley fleets made their annual visit then vanished again over the sea’s rim. Silence gripped the outpost for long months. When Andrea Giustinian was sent to Tana in 1396, he was staggered to discover nothing there – no people, no standing buildings – just the charred remains of habitations and the eerie crying of birds over the River Don. The whole settlement had gone down in fire and blood before an assault by Tamburlaine, the Mongol warlord, the previous year. In 1397 Giustinian appealed to the local Tatar lords for permission to build a new, fortified settlement. Venice simply started again. Tana was that important.

But in the centre of the eastern Mediterranean, Venice ran an imperial system of incomparable efficiency. Throughout the region, wherever the flag of St Mark was flown, the propaganda symbols of Venetian power – economic, military and cultural – were visible: in the image of the lion, carved into harbour walls and above the dark gateways of forts and blockhouses, growling at would-be enemies, offering peace to friends; in the bright roundels of its gold ducats, on which the doge kneels before the saint himself, whose purity and credibility undermined all its rivals; in the regular sweep of its war fleets and the spectacle of its merchant convoys; in the sight of its black-clad merchants pricing commodities in the Venetian dialect; in its ceremonies and the celebration of feast days; in its imperial architecture. The Venetians were omnipresent.

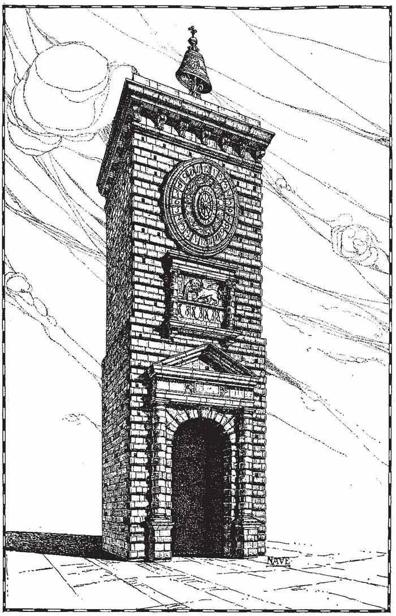

The city exported itself across the sea. Candia was styled alias civitas Venetiarum apud Levantem, ‘another city of the Venetians in the Levant’ – a second Venice – and it replicated its buildings and its emblems of power. There was the Piazza San Marco, faced by the Church of St Mark, a clock tower flying the saint’s flag, which like the bells of the campanile in Venice signalled the start and end of the working day, and the ducal palace and the loggia for conducting business and the buying and selling of goods. Two columns stood beside the palace for the execution of criminals, echoing those on the Venetian waterfront, reminding citizens and subjects alike that the writ of exemplary Venetian justice ran in the world. Here the Venetian state was reproduced in miniature: the chamber for weighing wholesale commodities using Venetian weights and measures, the offices dealing with criminal and commercial law, the antechambers and sub-departments of the Cretan administration, similar to those of the doge’s palace. Through half-closed eyes a travelling merchant could believe himself transported to some reflection of Venice, remade in the brilliant air of the Levant, like an image by Carpaccio repainting Venice on the shores of Egypt, or an English church in the Raj. Outsiders remarked on this trick of the light. ‘If a man be in any territory of theirs,’ wrote the Spanish traveller Tafur, ‘although at the ends of the earth, it seems as if he were in Venice itself.’ When he stopped at Curzola, on the Dalmatian coast, he found that even the local inhabitants had fallen under the Venetian sway: ‘The men dress in public like the Venetians and almost all of them know the Italian language.’ Constantinople, Beirut, Acre, Tyre and Negroponte all had a church of St Mark at one time or another.

Imperial monuments: the clock tower at Retimo

Such features made the travelling merchant or the colonial administrator feel that he occupied his own world; they fended off homesickness and projected Venetian power to their subjects, be they speakers of Greek, Albanian or Serbo-Croat. This was reinforced by the ritual elements of Venetian ceremonial. The formally orchestrated ceremonies so carefully detailed in fifteenth-century paintings were exported to the colonies. The arrival of a new duke of Crete, stepping from his galley to an announcement of trumpets under a red silk umbrella, met at the sea gate by his predecessor and walked in solemn procession up the main street to the cathedral and the anointment with holy water and incense – these were highly scripted demonstrations of Venetian glory. The stately processions, the banners of St Mark and the patron saints, the oaths of loyalty, submission and service to the Republic by subject peoples, the singing of the Lauds service in praise of the duke on the great feast days of the Christian year – these rituals fused secular and religious power in displays of splendour and awe. The pilgrim Canon Pietro Casola witnessed such ceremonial at a handover of the Cretan administration in 1494, which was ‘so magnificent that I seemed to be in Venice on a great festival’.

*

Colonial administration was organised in hierarchical tiers with regulated salary structures, privileges, obligations – and a litany of carefully differentiated titles. At its crest – the most powerful post in the system – was the duke of Crete; matching him for salary (a thousand ducats a year), to reflect the strategic importance of the place, was the bailo of Constantinople. Corfu and Negroponte were also governed by a bailo, Modon and Coron by two castellani, Argos and Naplion by a podesta. The islands of Tinos and Mykonos and the other towns of Crete were overseen by rectors; settlements on foreign soil – Tana or Salonica – were the province of consuls. These nabobs of the imperial system were elected, involuntarily, from the nobility of Venice, mandated to their posts and punished for refusal to serve. Beneath these titled people there fell away descending ranks of state servants: counsellors and treasurers, admirals of the colonial arsenals, notaries, scribes and judges, all of them sworn to act for the honour and profit of Venice, each of them apportioned certain rights, responsibilities and restrictions.

For all the pomp and gravitas invested in these state officers their freedom of manoeuvre was carefully circumscribed. Everyone felt the gravitational pull of Venice; even a consul in Tana three months’ sailing time away was subject to weighty regulation. The Republic was a centrist empire; everything was ruled, dictated, regulated from the lagoon and precisioned in an endless stream of edicts. An expectation of patriotism was hard-wired into the Venetian psyche; all its colonists came from the same few square miles of the lagoon; all were expected to act with unflinching patriotism for the Signoria. The Republic was obsessed with the racial purity of its citizens. Fear of going native, particularly after the Cretan revolt of 1363, haunted their edicts. Citizenship was rarely granted to foreigners and the frontiers of race were strictly patrolled. Intermarriage and defection to the Greek Orthodox Church were heavily frowned upon, and in the case of Crete actively penalised. High-ranking colonial officials were rotated on a two-year cycle to limit their potential for local contamination, and the centre worked hard to maintain cultural distinctions. At Modon, the Venetians were forbidden to grow beards; their citizens were to remain clean-shaven, distinguishable from the hirsute Greeks.

The conditions under which they served were closely defined. Governors were strictly instructed, under the terms of their commission, on the number of administrators in their retinue, the number of servants and horses that they must maintain for their prestige and use (the state was particular about the horses, neither fewer nor more), their pecuniary allowances and the limitations of their power. They were forbidden to engage in any commercial activity, or to take with them any relatives, and were bound by stern oaths. The Republic was wary of individual aggrandisement – an aversion to personal ambition was deeply ingrained in this most impersonal of states – and intolerant of corruption. Giovanni Bon, sent to Candia to manage its finances in 1396, not only swore the usual oath to act for the honour of Venice, he was bound to rent out the goods of the state at the highest price, to account in minute detail to the duke and his counsellors on an annual basis on everything that he dealt with and noticed during the previous year, to accept no services or gifts; both he and his employees were forbidden all commercial transactions or to offer any banquets to anyone, be they Greek or Latin, either in Candia or within a radius of three Venetian miles.

In a system where the doge himself was expressly barred from accepting gifts of any value from a foreign agency, such injunctions were standard. Its principles were continuous oversight and collective responsibility. No officer was to act alone. It required three keys, each held by a different treasurer, to open the Candia counting house. The duke of Crete required the written agreement of three counsellors to ratify a decision. Everything was built on documentary evidence. The secretarial corps toiling in the bowels of the doge’s palace, recording and despatching senatorial decrees to the Stato da Mar, was replicated at the local level. Every Venetian colony had its own notaries, scribes and document store. All decisions, transactions, commercial agreements, wills, decrees and judgements were set down in literally millions of entries, like an infinite merchant’s ledger, which formed the historic memory of the state. Everyone was accountable. Everything was written down. By the time of the death of the Venetian state, its archives ran to forty-five miles of shelving.

The records bear witness to the exhaustive central management of the imperial system – an endless struggle against corruption, nepotism, bribery and occasional acts of state treason. ‘The honour of the Commune demands that all its rectors be excellent’ was its mantra. The frequency with which commissions were accompanied by the injunction not to engage in trade suggests that breaches were many and various – and pursued with dogged persistence. Colonial officials at all levels had plentiful opportunity to feel the severe, impartial scrutiny of Venetian audit. Justice was patient, implacable and inexorable. No one was free from investigation. It fell on a duke with the same impersonal force as on a blacksmith. Its methods were exhaustive. At regular intervals, the syndics or provveditori – state inquisitors – made inspections. The sight of these black-robed functionaries stepping down the gangplank at Negroponte or Candia to ask questions and run the rule over the ledgers might strike anxiety in the most puffed-up colonial dignitary. Their powers were almost limitless. In the remit of May 1369 the provveditori are reminded that as well as auditing lower-level officials

A provveditore: auditor of the Stato da Mar

… their mission in the Levant has an equal bearing on the misdeeds of the governors themselves which might damage the state’s interests; the governors cannot refuse to respond about misdeeds with which they are charged, under any pretext, even if invoking the terms of their commissions. The provveditori are authorised to turn up wherever they think useful; their freedom of movement is limitless. Nevertheless [a typical Venetian caveat] they must endeavour to limit their travel costs. If an official happens to have committed an act of such seriousness that the provveditori suspect that he will not agree to go willingly to Venice to meet the charge, it will be necessary, after discussions with the local governor, to seize the guilty official and forcibly send him.

Accounts would be scrutinised, complaints heard, correspondence confiscated and dissected. The provveditori had a year on return to present their findings, to call further witnesses and impeach the guilty. And in a further dizzying level of audit, the inquisitors themselves, despatched usually in groups of three, were forbidden to trade, receive presents, even to lodge separately. The Stato da Mar ran on suspicion.

It was a month to Crete, six weeks to Negroponte, three months to Tana, but anyone could feel the long arm of the Venetian state. At times its reach could be very long indeed. In the spring of 1447, the senate received clandestine word that the duke of Crete himself, Andrea Donato, was consorting treacherously with the Milanese condottiere, Francesco Sforza, and taking bribes. The orders to detain him were brief and ruthless:

To Benedetto da Legge, galley captain, charged with arresting the duke: 1. He will go with all possible speed to Candia – all stops are forbidden. 2. At Candia he will anchor in the bay without landing. He will not allow anyone to disembark or come aboard. 3. He will send a trusted person to Andrea Donato, requesting him to come aboard to confer. 4. The pretext for the conversation will be to get information on the Levant situation, because the captain will pretend that he is going to Turkey to the sultan. 5. When Donato is on board, Benedetto will retain him, affirming that it is essential for him to come to Venice, without giving his reasons. 6. Before leaving Candia he will send the letter with which he is entrusted to the captain and counsellors of Crete. 7. In case Donato refuses to come aboard, or can’t, Captain Legge will send another letter, with which he is furnished, to the captain and counsellors, so that the duke will certainly come. 8. Once Donato is on board, the galley will depart for Venice at once, where … [the captain] will conduct him to the torture chamber. 9. During the whole voyage it is forbidden to speak to the prisoner; in the case that it is essential to put ashore, Donato must not land under any pretext whatsoever.

The accompanying sealed orders to the counsellors read: ‘In the case that Andrea Donato refuses to go on board the galley, the captain and counsellors must use physical force; they will put the duke under arrest and conduct him aboard so that he can be taken to Venice without delay.’ Da Legge made the journey in record time, plucked the duke off the island and hurried him back to Venice for torture. The round trip took a record forty-five days. The message was clear.

The Venetian state waged continuous war against the malfeasance of its officials; the registers ring with thunderous rebukes, inquiries, fines, impeachments and requests to torture. ‘It is forbidden …’ begin numerous entries, and the lists that follow are long and repetitive – to employ family members, sell public property, trade, and so forth. ‘Too many baili, governors and consuls obtain favours, allowances and various exemptions. This is intolerable and these practices are formally forbidden.’ A duke of Crete is arraigned for a grain scam; a chancellor of Modon–Coron is guilty of extortion; an official is fined for failing to take up a post; another is ordered back to account for a missing sum; the castellan of Modon, Francesco da Priuli, is arrested and snatched from his post – the vote to torture him is carried by thirteen to five, with five abstentions. Conversely, loyalty to the Republic was recognised and rewarded.

Venice applied its adamantine system to all the other subjects of the Stato da Mar. The governors were enjoined to deliver justice to all – to its Venetian colonists and subjects alike. The local populace, the Jews and other resident foreigners were subject to the same governance. By the standards of the times, the Republic possessed a strong sense of fairness which it wielded with considerable objectivity.

The Venetians were lawyers to their fingertips who operated the system with a fierce logic. In cases of murder there were fine gradations. Homicide was distinguished between simple (manslaughter) and deliberate, and divided into eight sub-categories, from self-defence and accidental, through deliberate, ambush, betrayal and assassination; judges were required to establish the motives as scrupulously as possible. (Actions of the secret state were of course exempt from such strictures: the registers for July 1415 record an offer to assassinate the king of Hungary. The assassin, ‘who wishes to remain anonymous, will also kill Brunezzo della Scala if he is found in the king’s company. The offer is accepted’.) The Republic could and did resort to hideous punishments; they used torture readily to procure the truth – or at least a confession – and they measured their judgements relative to state interests. In January 1368, one Gestus de Boemia was brought before the ducal court at Candia for theft of treasury money. His punishment was intended to be exemplary: amputation of his right hand, public confession of his crime, then hanging outside the treasury which he had raided. The following year, the Cretan Emanuel Theologite also lost a hand and both his eyes for letting a rebel prisoner escape. Toma Bianco had his tongue cut out for uttering insulting remarks against the honour of Venice, followed by imprisonment and perpetual banishment.

Venetian justice was also marked by moral repulsion: a butcher, Stamati of Negroponte, and his accomplice, Antonio of Candia, were condemned to death for male rape of a minor in January 1419; four months later Nicolo Zorzi was burned alive for the same offence. Capital sentences were carried out in the name of the doge for the edification of the populace – in Candia, between two columns in imitation of those in the Piazzetta of St Mark in Venice – yet within this harsh retributive framework decisions could be finely nuanced. Minors below the age of fourteen and the mentally handicapped were exempt from capital punishment, even in cases of assassination. The mentally ill were confined, and branded to advertise their condition. Everyone had right of appeal to Venice; witnesses could be called back to the mother city; cases could be reopened years later; even the Jews, marginalised subjects of the Venetian state, could expect a reasonable respect before the law. Justice ground slowly but with implacable respect for due process. In 1380, when the Venetian fleet was stationed at Modon one Giovannino Salimbene was found guilty of murdering Moreto Rosso. The judgement against Salimbene was deemed to have been ‘very badly handled, because of the circumstances, and above all the lack of witnesses’. Four years later the case was reopened with the order for ‘a new examination of the officers of the city’s night police’.

In this system, cases could be dismissed, mitigating circumstances allowed or judgements overturned on the vote of the relevant appeal body. In March 1415 a fine imposed on Mordechai Delemedego, ‘Jew of Negroponte’, is reversed – ‘the syndics do not have the right to act against the Jews’. The same year a similar fine imposed by the syndics on Matteo of Naplion, at Negroponte, for renting the Republic’s property whilst an officer of the state is annulled; ‘It has been proved that Matteo had resigned his post when he undertook these transactions’ ‘A judgement against Pantaleone Barbo – banned from public life for ten years – is reconsidered as ‘too severe for a man who has committed his life to the service of the Signoria, with exemplary loyalty’; Giacomo Apanomeriti, a Cretan, fined or alternatively sentenced to two years for raping a woman and refusing to marry her, is given a chance of reprieve. ‘The judges of appeal had examined this case: given the youth and poverty of the boy, he is released from all penalties if he marries the girl straight away.’

With its mixed populations of Catholics, Jews and Orthodox Christians, the Republic was concerned above all to keep a social balance. The Stato da Mar was essentially a secular state. It had no programme for the conversion of peoples, no remit to spread the Catholic faith – beyond the occasional leverage of papal support for particular advantage. Its opposition to the Orthodox Church on Crete was a fear of pan-Greek, nationalist opposition, rather than religious zealotry; elsewhere it could afford to be lenient. On docile Corfu, Venice decreed that the Greeks should have ‘liberty to preach and teach the holy word, provided only that they say nothing about the Republic or against the Latin religion’. It was equally alarmed by outbursts of undue fervour from the Catholic monastic orders who trailed in the wake of its conquests, and sometimes appalled. ‘The night watch have had to arrest four [Franciscans],’ it was reported from Candia in August 1420. ‘These men, holding a cross, processed completely naked, followed by a great crowd of people. Such acts are disagreeable.’ The Franciscans threatened a delicate cultural and religious balance. Any kind of civil unrest was to be feared. Two years later the doge wrote directly to the administration of Crete about

the sometimes scandalous reports on the behaviour of certain clerics of the Latin Church; this behaviour is all the more dangerous on Crete; one has just learned, in particular, that certain priests preach … to the detriment of the Signoria; the scandal has rebounded on the Venetians of the isle; the authorities will take immediate and rigorous measures against these priests, so that peace and tranquillity are restored on Crete.

Deep down Venice wished to keep the balance between its subjects: peace and tranquillity, honour and profit – the ideals went hand in hand.

But if the Republic could afford to be lenient in social matters, as far as security and civil peace allowed, economic pressure was felt everywhere. The colonies were zones of fiscal exploitation, taxed thoroughly and continuously, with the heaviest weight falling on the Jewish population. In matters of money the oppressive presence of the Dominante was inescapable. The central administration was endlessly concerned with collecting taxes. It had little concern as to how they were raised at the local level and there was almost no local say in how the proceeds were spent. The state managed its money like good merchants, accruing as much as possible, spending as little as necessary. Resource extraction was a central preoccupation.

From the Stato da Mar, Venice sought food, manpower and raw materials – sailors from the Dalmatian coast, Cretan wheat and hard cheese (a staple of the sailor’s diet), wine, wax, wood and honey. For the hungry urban population of the lagoon, these resources were vital. Crete was a critical support during the Chioggia war. Everything was funnelled directly back to the lagoon under strict conditions – even inter-colonial trade came via the mother city – and goods could only be transported in Venetian ships. Cargoes were scrupulously examined and heavy fines apportioned; each landfall at the customs house earned a small ingredient of state tax. The key products – salt and wheat – were commodity-traded at fixed prices, whose tariffs formed a subsidiary grievance of Cretan landowners, aware of greater gains to be made on an open market. The state registers minuted the operation of this oppressive system. The Dominante stipulated where, when, what and at what price goods could be transported across the Aegean and the Adriatic. It insisted on the use of its weights and measures and forced its currency on subject peoples. The ducat became as potent a symbol of Venetian power as the armed galley.

The effects of these central controls were keenly felt. The economic development of the shores of Greece was stifled, industry stunted (with the exception of Cretan shipbuilding), the opportunity for the growth of a local entrepreneurial class severely curtailed. Instead, Venice concentrated on the agricultural exploitation of its key domains. The terrain was unpromising: large areas of the Stato da Mar were mountainous, barren, short of water and hit by desiccating winds, but in the fertile valleys of Crete, Corfu and Negroponte, the Venetian administrations worked assiduously on irrigation and conservation of fertility. The Lasithi plateau, abandoned by edict under the revolts of the previous century, was brought back into cultivation. When Francesco Basilicata visited in 1630 it was described as ‘a very beautiful, flat area and an almost miraculous work of nature’.

The agricultural development of the Stato da Mar was always hampered by a shortage of manpower. People vanished from the fields. Plague and famine and the generally high mortality in the harsh landscapes took a heavy toll; the downtrodden peasantry sought continuously to evade oppressive Venetian control; slaves escaped; pirates snatched whole populations – the continuous draining away of human resources was a running complaint. In 1348, the Signoria could lament that ‘the pitiful epidemic which has just ravaged Crete and the resulting high number of deaths require steps taken to repopulate. In particular it is necessary to give confidence to fleeing debtors so that they return to work their land. The landlords lack men.’ By the late fourteenth century slaves from the Black Sea were being imported to work the land in a plantation-style system. For the indigenous Greek peasantry life had always been hard; under its colonial overseers it became no easier. Venetian rule paid scant attention to its rural workforce; they were a resource, like wood or iron, used without curiosity. When later, more compassionate observers visited Crete they were startled by what they saw. Four hundred years of Venetian rule produced few gains for its subjects: ‘the deprivation of the Cretan people defies credibility,’ wrote a seventeenth-century observer. ‘There must be few in the world who live in such miserable conditions.’ What Venice offered back was just some measure of security against pirate raids.

Colonial administration was a work of continuous oversight, microcosmically managed from the distant lagoon. The exhaustive detail of the state registers bears witness to the attention that Venice paid to the Stato da Mar. The millions of entries set out its preoccupations and obsessions. Here are precise instructions for galley fleets – when they can sail, how long they can land for, what they can sell – price incentives for shipping Cretan wheat, permits to trade, taxes for repairing city walls, accounts of corruption and street brawls, Turkish pirates and shipwrecks. Losses are lamented and blame apportioned. There are the persistent and endless demands for restitution. No detail seems too small for the telescopic vision of the state, recorded by inky clerks toiling in the windowless bowels of the doge’s palace: a murder is documented in Constantinople; a Genoese privateer noted in the Cyclades; a hundred crossbowmen are ordered to Crete; 4,700 sacks of ship’s biscuit must be prepared for the galleys; the chancellor of Negroponte has too much work; a courageous galley commander loses an arm in battle; the widow of the duke of Crete has purloined two gold cups and a carpet belonging to the state.

Proficium et honorem – profit and honour – are the two persistent accusatives that echo through the record of this colossal and exhaustive enterprise. If profit was the ultimate driver, the Republic gloried in the naming of its colonies and counted them proudly like gold ducats in a merchant’s chest. It bestowed on them swelling titles that emphasised their structural importance – ‘the Right Hand of our city’, ‘the Eyes of the Republic’ – as if they were organic parts of the Venetian body. To its inhabitants Venice was less a few finite miles of cramped lagoon than a vast space, vividly imagined, extending ‘wherever water runs’, as if from the campanile of St Mark, distance were foreshortened and Corfu, Coron, Crete, Negroponte, the Ionian Isles and the Cyclades were plainly visible, like diamonds on a silk sea. Damage to the Stato da Mar was felt like a wound; losses like an amputation.

The Stato da Mar was the city’s unique creation. If it drew on Byzantine tax structures, in all other respects its management was the reflection of Venice itself. The empire represented Europe’s first full-blown colonial experiment. Held together by sea power, largely uninterested in the well-being of its subjects, centrifugal in nature and economically exploitative, it foreshadowed what was to come. It probably cost Venice more than was ever directly extracted in taxes, food and wine, but ultimately it was worth it. Beyond the produce and revenue, it provided the stepping stones across the eastern sea, the naval bases to protect its fleets, the stopping places for its galleys, the entrepôts and marts for storing goods, the back stations to retreat to in hard times. And this second wave of imperial expansion allowed Venice to do something else: to dominate, for a time, the trade of the world.