‘A Dog Returning to its Vomit’

OCTOBER 1202–JUNE 1203

The Venetians had every intention of using this magnificent fleet along the way to reassert their imperial authority in the upper Adriatic, to cuff insubordinate cities, threaten pirates and levy sailors. Where Venice saw this as a legitimate assertion of feudal rights, many of the crusaders, frustrated and impoverished by the long wait on the Lido, already perceived the whole venture as a perversion of crusading vows. ‘They forced Trieste and Mugla into submission,’ an anonymous chronicler bluntly asserted as the fleet worked its way down the coast, ‘they compelled all of Istria, Dalmatia, and Slavonia to pay tribute. They sailed into Zara, where their [crusading] oath came to naught. On the feast of Saint Martin they entered Zara’s harbour.’ Venetian ruthlessness was not always well received.

The fleet smashed through the harbour chain, forced its way in and proceeded to disembark thousands of men. The doors of the transports were prised open; the groggy, disorientated horses were led blindfolded onto dry land; catapults and siege towers were unloaded and assembled; a host of tents, with banners flying, was pitched outside the city walls. The Zarans surveyed this ominous enterprise from their battlements and decided to surrender. Two days after the fleet’s arrival they sent a delegation to the crimson pavilion of the doge to offer terms. The business of Zara was a purely Venetian matter, but Dandolo, either out of scrupulousness or a desire to make the Zarans sweat, declared that he could not possibly accept this until he had conferred with the French barons. He left the delegation kicking its heels.

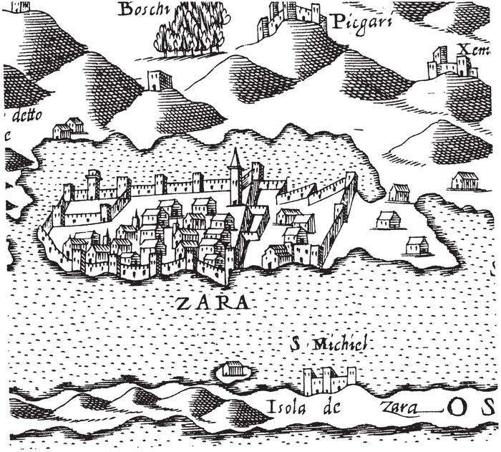

Zara and its harbour

Unfortunately for Dandolo – and as it turned out even more unfortunately for Zara – at almost the same moment a ship arrived from Italy carrying the furious interdict of Pope Innocent. The actual letter is lost but its contents were clearly restated later:

… we took care to strictly enjoin in our letter, which we believe came to your attention and that of the Venetians, that you not be tempted to invade or violate the lands of Christians … Those, indeed, who might presume to act otherwise should know that they are bound by the fetters of excommunication and denied the indulgence that the [pope] granted the crusaders.

This was extraordinarily serious. Excommunication threatened, at a stroke, to damn the very souls crusading was intended to save. The letter was a grenade thrown into the expedition’s uneasy pact and it opened up all the underlying tensions of the enterprise. A dissenting group of French knights, led by the powerful Simon de Montfort, had always seen the diversion to Zara as a betrayal of crusader vows. While Dandolo was elsewhere discussing the surrender with a body of crusader lords, they called on the Zaran delegation waiting at the doge’s tent. They informed it that the French would refuse to attack the city, and ‘if you can defend yourself against the Venetians, then you will be safe’. Just to make sure the message got across, another knight shouted this information over the battlements. Armed with this promise the Zaran delegation turned on its heels and went back to the city, determined to resist.

Dandolo, meanwhile, had got the agreement of the majority of the leaders to accept the surrender and they all returned to his tent. Instead of the Zaran delegation, which had vanished, they were confronted by the abbot of Vaux, probably with Innocent’s letter in his hand, who stepped dramatically forward with all the force of papal authority and declared: ‘Lords, I forbid you, by the pope in Rome, to attack this city; for it is a place of Christians and you are pilgrims.’ A furious row broke out. Dandolo was incensed and rounded on the crusader leaders: ‘Sirs, by agreement I arranged the surrender of this city, and your men have taken it from me, although you gave me your word that you would help me to conquer it. Now I call on you to do so.’ Furthermore, according to Robert of Clari, he was not prepared to back down before the pope: ‘Lords, you should be aware that I won’t relinquish my vengeance on them at any price, not even for the pope!’

The crusader leaders, more squeamish, found themselves caught between excommunication and the breaking of a secular agreement. Shamefaced and appalled by de Montfort’s actions, they decided they had no option but to underwrite their commitment to the Venetian cause – the outstanding debt was tied up in the deal. Otherwise the crusade might just collapse. It was with heavy hearts that they agreed to this unpalatable act: ‘Sir, we will help you to take the city despite those who want to prevent it.’ The unfortunate Zarans, who had tried to surrender peacefully, now found themselves subjected to overwhelming force. They tried to prick crusader consciences by hanging crosses from the walls. It made no difference. Giant catapults were wheeled up to bombard the walls; miners began to tunnel beneath them. It was all over in five days. The Zarans sued for peace on more humiliating terms. Barring a few strategic executions, the Venetians spared the citizens’ lives; the city was evacuated and the victors ‘looted the city without mercy’.

It was now mid-November and Dandolo pointed out to the assembled army that it was too late in the year to sail on; the winter could be passed pleasantly enough in the mild climate of the Dalmatian coast. It would be better to wait until spring. It was reasonable enough, unavoidable even, but this suggestion seems to have plunged the crusade into fresh crisis. The rank-and-file crusaders felt they were being yet again shamelessly exploited – and they largely blamed Venice. They had been imprisoned on the Lido, led astray to attack Christian cities, impoverished and deceived. The clock was ticking steadily on the year’s contract with Venice and they were no step nearer the Holy Land, let alone Egypt. The spoils of Zara had been largely appropriated by the lords. ‘The barons kept the city’s goods for themselves, giving nothing to the poor,’ wrote an anonymous eyewitness, evidently sympathetic to the plight of the common man. ‘The poor laboured mightily in poverty and hunger.’ Collectively they still owed thirty-four thousand marks.

Shortly after the sacking of Zara, popular resentment erupted into violence.

Three days later, a terrible catastrophe befell the army near the hour of vespers, because a wide-ranging and very violent fight broke out between the Venetians and the French. People came running to arms from all sides and the violence was so intense that in nearly every street there was fierce fighting with swords, lances, crossbows and spears, and many men were killed or wounded.

It was with considerable difficulty that the commanders regained control of the situation. The crusade was hanging by a thread.

What the ordinary crusaders did not know – and this would have horrified them far more – was that they had now been excommunicated for the attack on the city. In an exercise of creative crisis management, the crusading bishops simply bestowed a general absolution on the army and lifted the ban, which they had no authority to do. Over the winter of 1202–3 the rank and file whiled away the time on the Dalmatian coast in reasonable accord whilst waiting for the new sailing season, blissfully unaware that their immortal souls were still in grave peril. The Frankish barons decided to hurry an abjectly apologetic delegation back to Rome to try to sort the situation out. The Venetians refused point-blank to participate: Zara was their own business; on its capture was built the agreement which would lead to the return of the thirty-four thousand marks and as long as this debt remained outstanding, the whole Republic’s position was critical.

Even before this delegation had left for Rome, word of Zara had reached Innocent and he was drafting a furious response. It began tersely enough: ‘To the counts, barons and all the crusaders without greeting’ and went downhill from there. In a series of battering sentences, like the rhythmic thud of a siege engine, he castigated the crusaders for their ‘very wicked plan’:

You set up tents for a siege. You entrenched the city on all sides. You undermined its walls, not without spilling much blood. And when the citizens wanted to submit to your rule and that of the Venetians … they hung images of the cross from their walls. But you … to the not insignificant injury to Him who was crucified, you attacked the city and its people, you compelled them to surrender by violent skill.

He reminded the hangdog delegation when it arrived that the absolution granted by the bishops was absolutely illegal. He demanded repentance and restitution of the spoils. But his ultimate condemnation was reserved for the Venetians who ‘knocked down the walls of this same city in your sight, they despoiled churches, they destroyed buildings, and you shared the spoils of Zara with them’. In the biblical analogy of the man who fell among thieves, the Venetians were cast as the plunderers, leading the crusade astray. Innocent also insisted that no more damage be done to Zara – an order the Venetians would roundly ignore – but at the same time, considering the crusaders’ plight and his own ardent desire that his crusade should not disintegrate, he established a process by which absolution could be achieved – from which the Venetians were pointedly excluded. Due to the fact that the letter with which the delegation returned plainly stated that the army was, as yet, still under papal ban and that some of its terms, such as the return of the spoils, were simply not going to be met, the contents were again suppressed. It was given out that full absolution had been granted. The pope’s ability to manage his crusade was plainly limited.

*

If Innocent thought that his deepest fears about the snares of a sinful world had been realised, he was wrong. Things were about to get far worse. The propulsive forces that drove the whole enterprise forward – the spiritual thirst, the Venetian debt, the shortage of funds, the secret agreements, the continuous betrayals of the rank and file, the repeated threat of disintegration, the months passing on the maritime contract – these were about to deliver another extraordinary twist to the direction of events. On 1 January 1203, ambassadors came to Zara from Philip of Swabia, king of Germany. They brought with them an enterprising proposal for the crusade to consider. It involved the whole complex back story of Byzantium and its fraught relationship with western Christendom. And like many of the secret deals that ensnared and propelled the crusade, its contents were already known to some of the leading knights.

Put baldly, the ambassadors said this: they had come on behalf of Philip’s brother-in-law, a young Byzantine nobleman called Alexius Angelus, to plead for help in regaining his rightful inheritance – the throne of Byzantium – from his uncle. Angelus’s father, Isaac, had been deposed and blinded by the present emperor, Alexius III. In fact, by the strict laws of succession, the young man had no rightful claim to the throne, but the niceties of Byzantine imperial protocol were probably lost on the French knights. The ambassadors came with a cunningly framed and carefully timed proposal that suggested an intimate knowledge of the crusaders’ plight. It combined a garbled appeal to Christian morality with an offer of hard cash:

Since you campaign for God, right and justice, you must also return the inheritance to those who have been wrongly dispossessed, if you can. And Angelus will give you the best terms that anyone has ever offered to a people and the most valuable help in conquering the land overseas.

Firstly, if God allows you to restore his inheritance to him, he will put the whole of Romania [Byzantium] in obedience to Rome, from which it has been severed. Next, because he understands how you have given everything you have for the crusade so that you are now poor, he will give two hundred thousand silver marks to the nobles and the ordinary people together. And he himself will personally go with you to the land of Egypt with ten thousand men … he will perform this service for a year, and for the rest of his life he will maintain five hundred knights in the land overseas at his own expense.

The terms were extraordinarily generous. They seemed to offer everything to everyone. The papacy could achieve one of its most ardent objectives: submission of the Orthodox Church in Constantinople to Rome; the crusaders could not only handsomely repay their debt, they would gain the military resources both to conquer and to retain the Holy Land. The pope, it was suggested, would actually welcome such an action. And it would be easy: Angelus had many supporters in Constantinople; the gates would be flung open to welcome the liberators from his tyrannical uncle, the emperor Alexius III. ‘Sirs,’ concluded the envoys in the tone of persuasive salesmen offering a once-in-a-lifetime bargain, ‘we have full authority to conclude these negotiations should you wish to do so. And you should be aware that such generous terms have never been offered to anyone. He who turns them down obviously has no real appetite for conquest.’

Some of what they said was wish-fulfilment; some was simply untrue. In fact Angelus had called on Innocent with an outline of this plan the previous autumn and been given a very dusty response. Innocent had already warned the crusaders off supporting such a scheme, which would involve yet another attack on Christian lands, ‘lest, by any chance, fouling their hands with the massacre of Christians, they commit a sin against God’, and had written to the Byzantine emperor to say that he had done so. Alexius Angelus was young, ambitious and foolish. He was making unwise promises he could not guarantee, telling the crusader lords what they wanted to hear. But an inner circle of Frankish barons was already acquainted with the scheme and they were receptive. Boniface of Montferrat, the leader of the whole venture, had family grievances against the Byzantine emperor. Afterwards Innocent would lay the blame for what ensued squarely on the Venetians, but it was not their idea. It is uncertain if Dandolo knew in advance of the plan to divert the crusade to Constantinople; it is likely that he appraised it with a very cool eye. He certainly knew much more about the inner workings of Constantinople than most of the French barons, and he did not invest much confidence in the young Angelus. As for Angelus, the treaty being put forward in his name would eventually cost him his life.

The decision as to whether to attack a second Christian city on their way to the Holy Land was put to a restricted council of secular and religious leaders at Zara the next day. It immediately reopened furious and schismatic debate, which threatened, yet again, to jeopardise the whole expedition. Opinion was sharply divided. The abbot of Vaux again railed against it ‘for they had not agreed to wage war against Christians’; on the other side an iron pragmatism was put forward: the army was short of funds, the debt remained outstanding, this would provide both money and men to retake the Holy Land: ‘You should know that the Holy Land overseas will only be recovered via Egypt or Greece [Byzantium], and that if we turn down this offer we will be shamed forever.’ Dandolo must have weighed it carefully: the debt would be handsomely repaid and an emperor favourable to their interests would be highly valuable in Constantinople, yet the Venetians also had a lot to lose. The Republic was once more trading profitably there and its resident merchants would again make easy hostages if the bid failed, but poverty was ultimately the driver of events. The crusade could simply fail for lack of money and food; if Angelus could easily be installed, Dandolo reasoned that ‘we could have a reasonable excuse for going there and taking the provisions and other things … then we should well be able to go overseas [to Jerusalem or Egypt].’ After careful consideration he decided to join those in favour, ‘partly’, declared one anti-Venetian source, ‘in the hope of the promised money (for which that race is extremely greedy), and partly because their city, supported by a large navy, was in fact arrogating to itself sovereign mastery over that entire sea’. This was a retrospective judgement of the way things fell out.

Eventually, a powerful caucus of French barons, led by Boniface, overrode all objections and voted to accept the proposal. It was quickly signed and sealed in the doge’s residence. Alexius was to arrive two weeks before Easter. It was effectively stitched up – and had possibly been agreed in outline long before the crusade set sail. The common crusaders would be taken wherever their feudal masters wanted and the Venetians sailed. Even Villehardouin had to admit that ‘this book can only testify that among the French party only twelve swore oaths, no more could be obtained’. He conceded that it was highly contentious: ‘so the army was in discord … Know that men’s hearts were not at peace, because one of the parties worked to break up the army, the other to hold it together.’ There were significant defections. Many of the rank and file ‘gathered together and, after having made a compact, swore they would never go there’. A number of high-ranking knights, similarly disgusted, took the same course. Some returned home, disappointed; others sought passage direct to the Holy Land. Five hundred were lost in a shipwreck. Another band was set upon and massacred by Dalmatian peasants. ‘So the army continued to dwindle day after day.’

Innocent, meanwhile, as yet unaware of this latest – and more heinous – act of wickedness, followed up his previous threats with an explicit excommunication of the unrepentant Venetians, but his hold over the crusade was weakening by the day. Yet again its leaders simply suppressed the letter. Then, just as the fleet was preparing to sail south, they despatched a half-hearted apology for doing so back to Rome, safe in the knowledge that they would be out of earshot by the time any response could come. It was accompanied by the disingenuous explanation that Innocent would actually have preferred them to suppress his letter than let it lead to the break-up of the expedition! ‘We are confident’, they wrote, ‘that it is more pleasing in your sight, that … the fleet remain together than it be lost by a sudden display of your letter.’ When Dandolo finally got round to apologising two years later, he would use the same get-out.

On 20 April, with all the equipment, horses and men reembarked, the bulk of the fleet set sail for Corfu. By this time, the Venetians, far from repentant, had razed Zara to the ground: ‘its walls and towers, palaces too, and all its buildings’. Only the churches were left intact. Venice was determined that the rebellious city should be incapable of further defiance. Dandolo and Montferrat remained in Zara; they were waiting for Alexius, the young pretender. He turned up five days later – on St Mark’s Day, a carefully timed arrival – ‘and was received with a celebration of unmeasurable festivity by the Venetians who were still there’. They then embarked on galleys and followed the army down to Corfu.

The crusade was lurching from crisis to crisis – its need for cash being continuously set against the distasteful means of obtaining it – and the arrival of the young pretender seems to have prompted a further wave of revulsion amongst the faithful. In Corfu Alexius was initially received with all the trappings of imperial majesty by the leading Frankish barons, who ‘greeted him and then treated him with great pomp. When the young man saw the high-born men honouring him like this, and the force that was there, he was more joyful than any man had ever been before. Then the marquis came forward and conducted him to his tent.’ And there, according to the count of Saint-Pol, Alexius resorted to his own emotional blackmail: ‘on bent knees and drenched in tears, he implored us as a supplicant that we should go with him to Constantinople’. It was a tactic that misfired badly. There was, according to Saint-Pol, ‘great uproar and dissent. For everyone was shouting that we should hurry to Acre, and nor were there more than ten who praised the idea of making the journey to Constantinople.’ Robert of Clari put the views of the ordinary man more bluntly: ‘Bah! What are we doing with Constantinople? We have our pilgrimage to make … and our fleet is to follow us for only a year, and half of it has gone by already.’

So furious was the controversy that a large dissenting group of leading Franks left the camp and set themselves up in a valley some distance away. Panic infected the crusader command. According to Villehardouin ‘they were mightily distressed and said “Sirs, our situation is dire: if these men leave us … our army will be lost.”’ In a make-or-break attempt to prevent the crusade’s total collapse, they set out on horseback to beg the dissidents to reconsider. The atmosphere, when the two parties met, was highly charged. Both groups dismounted and walked cautiously towards each other, uncertain what would happen. Then,

… the barons fell at their feet, all weeping, and said that they would not get up until those who were there promised not to leave them. And when the others saw this, they were moved to great compassion and wept bitterly when they saw their lords, their relatives and their friends fall at their feet.

It was an extraordinary piece of manipulation – and it worked. The dissidents were overwhelmed by this raw emotional appeal and agreed to go forward, on strict terms. It was now mid-May and the Venetian ship lease was running out. They would stay at Constantinople only until 29 September. The leaders had to swear that when this time came they would provide ships to the Holy Land at two weeks’ notice. They set sail from Corfu on 24 May. According to Villehardouin, always ready to put the most positive spin on events, the day

was fine and clear, the wind soft and gentle and they unfurled their sails to the breeze … and such a fine sight was never seen. It seemed that this fleet would certainly conquer lands because as far as the eye could see, one could behold nothing but sails, ships and other craft, so that men’s hearts rejoiced greatly.

The crusade had survived by the skin of its teeth.

And yet for those who could see, the Corfu stay should have given further pause for thought. Alexius had promised that the Byzantines would recognise the justice of his claim, that the gates of Constantinople would be flung wide to welcome him and then the Orthodox Church would bow to the supremacy of Rome. Nothing at Corfu presaged such an outcome. The citizens remained loyal to the ruling emperor, kept their gates shut and bombarded the Venetian fleet in the harbour, forcing it to withdraw. As for the religious schism, when the Orthodox archbishop of Corfu invited some of his Catholic brethren to lunch, he remarked that he could see no basis for Rome’s primacy over his church, other than the fact that it had been Roman soldiers who had crucified Christ.

*

Back in Rome, Innocent’s worst fears had been confirmed. He had now learned that, after sacking Zara, the crusaders were sailing for Constantinople. On 20 June he penned another blast: ‘Under threat of excommunication we have forbidden you to attempt to invade or violate the lands of Christians … and we warn you not to contravene this prohibition lightly.’ Expressing his utter revulsion at the possibility of redoubled sin, he summoned up the most distasteful metaphor at his command: ‘A penitent returning to his sin is regarded as a dog returning to its vomit.’ The letter makes quite clear whom Innocent held responsible for this state of affairs. Dandolo is likened to Pharaoh in Exodus, who ‘under a certain semblance of necessity and the veil of piety’ kept the crusaders, as the children of Israel, in bondage. He is ‘a person hostile to our harvest’, a trifle of leaven ‘corrupting the whole mass’. Innocent commanded the crusader leaders to present the letter of excommunication to the Venetians, ‘so that they cannot find an excuse for their very sins’. At the same time he was wrestling with the tricky theological problem as to how the crusaders might consort with the excommunicated Venetians on the ships. His elliptically worded solution was startling: they might travel with them to the Holy Land, ‘where, seizing the opportunity, you might suppress their malice, insofar as it is expedient’. Decoded, it suggested that the unrepentant Venetians might justifiably be destroyed.

But everyone in the fleet, willingly or otherwise, was in this together, and it was far too late. With a fair wind, the fleet was making steady progress towards the Dardanelles even as Innocent set pen to paper. Four days later, on 24 June 1203, the crusaders were in the Bosphorus, looking up, astonished, at the impregnable walls of Constantinople. Events had drifted well beyond Innocent’s control. The following month he sorrowfully acknowledged as much: ‘For here the world ebbs and flows like the sea, and it is not easy for someone to avoid being driven hither and thither in the ebb and flow, or for him, who does not stay in the same place, to remain unmoved in it.’ The maritime image was telling.