A Quarter and Half a Quarter

1204–1250

By the partition of Byzantium in October 1204, Venice became overnight the inheritor of a maritime empire. At a stroke, the city was changed from a merchant state into a colonial power, whose writ would run from the top of the Adriatic to the Black Sea, across the Aegean and the seas of Crete. In the process its self-descriptions would ascend from the Commune, the shared creation of its domestic lagoon, to the Signoria, the Serenissima, the Dominante – the dominant one – a sovereign state whose power would be felt, in its own proud formulation, ‘wherever water runs’.

On paper the Venetians were granted all of western Greece, Corfu and the Ionian islands, a scattering of bases and islands in the Aegean Sea, critical control of Gallipoli and the Dardanelles, and most precious of all, three eighths of Constantinople, including its docks and arsenal, the cornerstone of their mercantile wealth. The Venetians had come to the negotiating table with an unrivalled knowledge of the eastern Mediterranean. They had been trading in the Byzantine Empire for hundreds of years and they knew exactly what they wanted. While the feudal lords of France and Italy went to construct petty fiefdoms on the poor soil of continental Greece, the Venetians demanded ports, trading stations and naval bases with strategic control of seaways. None of these were more than a few miles from the sea. Wealth lay not in exploiting an impoverished Greek peasantry, but in the control of sea lanes along which the merchandise of the east could be channelled into the warehouses of the Grand Canal. Venice came in time to call its overseas empire the Stato da Mar, the territory of the sea. With two exceptions it never comprised the occupation of substantial blocks of land – the population of Venice was far too small for that – rather it was a loose network of ports and bases, similar in structure to the way stations of the British Empire. Venice created its own Gibraltars, Maltas and Adens, and like the British Empire it depended on sea power to hold these possessions together.

This empire was almost an accidental construct. It contained no programme for exporting the values of the Republic to benighted peoples; it had little interest in the lives of these unwilling subjects; it certainly did not want them to have the rights of citizens. It was the creation of a city of merchants and its rationale was exclusively commercial. The other beneficiaries of the partition of 1204 concocted scattered kingdoms with outlandish feudal titles – the Latin Empire of Constantinople, the kingdom of Salonica, the despotate of Epirus, the megaskyrate of Athens and Thebes, the triarchy of Euboea, the principality of Achaea, the marquisates of Boudonitza and Salona – the list was endless. The Venetians styled themselves quite differently. They were proud lords of a Quarter and Half a Quarter of the Empire of Romania. It was a merchant’s precise formulation, coming in total to three eighths, like a quantity of merchandise weighed in a balance. The Venetians, shrewdly practical and unromantic, thought in fractions: they divided their city into sixths, the capital costs of their ships into twenty-fourths and their trading ventures into thirds. The places where the flag of St Mark was raised and his lion carved on harbour walls and castle gates existed, in the repeated phrase, ‘for the honour and profit of Venice’. The emphasis was always on the profit.

The Stato da Mar allowed the Venetians to ensure the security of their merchant convoys and it protected them from the whims of foreign potentates and the jealousy of maritime rivals. Crucially, the treaty afforded unequalled control of trade within the centre of the eastern Mediterranean. At a stroke it locked their competitors, the Genoese and the Pisans, out of a whole commercial zone.

Theoretically Byzantium had now been neatly divided into discrete blocks of ownership, but much of this existed only on paper, like the crude maps of Africa carved up by medieval popes. In practice it was far messier. The implosion of the Greek empire shattered the world of the eastern Mediterranean into glittering fragments. It left a power vacuum, the consequences of which no one could foresee –the irony of the Fourth Crusade was that it would advance the spread of Islam, which it had set out to repel. The immediate aftermath was less an orderly distribution than a land grab. The sea became a Wild East for adventurers and mercenaries, pirates and soldiers of fortune from Burgundy, Lombardy and the Catalan ports. It was a last Christian frontier for the young and the bold. Tiny principalities sprang up on the islands and plains of Greece, each one guarded by its desolate castle, engaging in miniature wars with its neighbours, feuding and killing. The history of the Latin kingdoms of Greece is a tale of confused bloodshed and medieval war. Few of them lasted long. Dynasties conquered, ruled and vanished again within a couple of generations, like light rain into the dry Greek earth. They were dogged by continuous, if uncoordinated, Byzantine resistance.

Venice knew better than most that Greece was no El Dorado. True gold was coined in the spice markets of Alexandria, Beirut, Acre and Constantinople. They impassively watched the feudal knights and mercenary bands hack and hatchet each other and pursued a careful policy of consolidation. They hardly bothered with many of their terrestrial acquisitions. They never claimed western Greece, with the exception of its ports, and unaccountably failed to garrison Gallipoli, the key to the Dardanelles, at all. Adrianople was assigned elsewhere for lack of Venetian interest.

The Venetians’ eyes remained fixed on the sea but they had to fight for their inheritance, continuously dogged by Genoese adventurers and feudal lordlings. This would involve them in half a century of colonial war. Venice was granted the strategic island of Corfu, a crucial link in the chain of islands at the mouth of the Adriatic, but they had to oust a Genoese pirate to secure it and then lost it again five years later. In 1205, they bought Crete from the crusader lord Boniface of Montferrat for five thousand gold ducats, then spent four years expelling another Genoese privateer, Henry the Fisherman, from the island. They took two strategic ports on the south-west tip of the Peloponnese, Modon and Coron, from pirates, and established a foothold on the long barrier island of Euboea, which the Venetians called Negroponte (the Black Bridge), on the east coast of Greece. And in between they occupied or sublet a string of islands round the south coast of the Peloponnese and across the wide Aegean. It was out of this scattering of ports, forts and islands that they created their colonial system. Venice, following the Byzantines, referred to this whole geographic area as Romania – the kingdom of the Romans, the word the Byzantines used for it – and divided it up into zones: Lower Romania, which constituted the Peloponnese, Crete, the Aegean islands and Negroponte, and Upper Romania, the lands and seas beyond, up the Dardanelles to Constantinople itself. Further still lay the Black Sea, a new zone of potential exploitation.

The cardinal points of the system were the twin ports of Modon and Coron (so frequently linked in Venetian documents as almost to constitute a single idea), Crete and Negroponte. This triangle of bases became the strategic axis of the Stato da Mar, and over the centuries Venice would fight to the death for their retention. Modon and Coron, twenty miles apart, were Venice’s first true colonies, so critical to the Republic’s maritime infrastructure that they were called ‘the Eyes of the Republic’ and declared to be ‘so truly precious that it is essential that we provide whatever is required for their maintenance’. They were vital stepping stones on the great maritime highway and Venice’s radar stations. Information was as invaluable for the merchants on the Rialto as ready coin; it was compulsory for all ships returning from the Levant to stop there and pass news of pirates, warfare and the price of spices.

Modon

Modon, with its encircling harbour ‘capable of receiving the largest ships’ capped by a fort fluttering the flag of St Mark, animated by turning windmills, bastioned by towers and thick walls to shield it from a hostile hinterland, provided arsenals, ship repair facilities and warehouses. ‘The receptacle and special nest of all our galleys, ships and vessels on their way to the Levant’, it was labelled in official documents. Here ships could mend a mast, replace an anchor, hire a pilot; obtain fresh water and trans-ship goods; buy meat and bread and watermelons; venerate the head of St Athanasius or try the heavily resinated local wines, which ‘are so strong and fiery and smell of pitch so that they can’t be drunk’, one passing pilgrim complained. When the merchant fleets pulled in on their way east, the ports were transformed into vivid fairs where every oarsman with a little merchandise under his rowing bench would set up his wares and try his luck. Modon and Coron were the turntables of the Venetian sea. From here one route headed east. Galleys could tip the spiked fingers of the Peloponnese, drifting past the ominous headland of Cape Matapan, once the entrance to the underworld, and head for Negroponte, on the way to Constantinople. The other, more essential trunk route led south via the barren stepping-stone islands of Cerigo and Cerigotto to Crete – hub of the Venetian system.

The bases, harbours, trading posts and islands that Venice inhabited after 1204 were part of the commercial and maritime network that sustained its trading activities. If taxed heavily, they were generally ruled lightly. Crete however was different. The Great Island, ninety miles long, lying across the base of the Aegean like a limestone barrier buffering Europe from the African shore, resembled less an island than a complete world; a harsh intractable series of separate zones, spined by three great mountain ranges, intercut with deep ravines, high plateaus, fertile plains and thousands of mountain caves. Crete spawned Zeus and Kronos, the primitive gods of the Hellenic world; it was a landscape of wildness, banditry and ambush. For Venice, its occupation was like a snake attempting to swallow a goat. Crete’s population was five times that of Venice and its people fiercely independent, utterly loyal to the Orthodox faith and the Byzantine Empire, in whose destruction the Venetians were deeply complicit. Crete had been cheap to buy. Owning it would cost a fortune in money and blood.

From the start, there was spirited resistance. It took a dozen years to oust the Genoese in military ventures that cost Dandolo’s son, Ranieri, his life. Venice then embarked on a process of military colonisation. It tried to remake the island as an enlarged model of itself, breaking it into six regions, the sestieri, as in Venice, and inviting settlers from each Venetian sestiere to settle in the area that was given the same name. Waves of colonists left their home city to try their luck in this new world with promises of land holdings in return for military service. The outflow of population was considerable. In the thirteenth century, ten thousand Venetians settled on Crete, out of a population that never numbered more than a hundred thousand, and many of the aristocratic names of the Republic, such as Dandolo, Querini, Barbarigo and Corner, were represented. Still, the Venetian presence on the island was always small.

Crete was Venice’s full-blown colonial adventure, which would involve the Republic in twenty-seven uprisings and two centuries of armed struggle. Each new wave of settlers sparked a fresh revolt, led by the great Cretan landowning families, deprived of their estates. The Venetians, essentially urban people, consolidated their hold on the three principal cities on the northern coast: Candia (the modern Heraklion), the hub of Venetian Crete, and further west the cities of Retimo and Canea. The countryside nominally pinned down by a series of military forts was more tenuously held, and among the limestone fastnesses of Sphakia and the White Mountains, where warrior clans lived by banditry and heroic song, no Venetian writ ran at all. Venetian rule was harsh and indifferent; the island was managed directly from the mother city by a duke, answerable to the Republic’s senate, a thousand miles away. Venice mulcted Crete with particular ferocity, worked its peasantry hard to extract grain and wine for the mother city, and repressed the Orthodox Church. Fearful of Byzantine national sentiment, which burned most brightly among the Orthodox clergy, spreading across the Aegean, they banned all priests from outside the island. The Republic practised an uncompromising policy of racial separation. No man could hold a post in the island’s administration unless he was ‘flesh of our flesh, bone of our bone’ as the formula ran; the fear of going native echoes through the Venetian records. Conversion to Orthodoxy meant immediate loss of a Venetian’s land holdings. The colonists were fond of quoting St Paul’s unflattering words on the Cretans: ‘always liars, evil beasts, slow bellies’. The Cretan peasantry were downtrodden and poor – and continued so for all the 450 years of Venetian rule.

The Cretans, arbitrarily taxed, exploited and stripped of their privileges, rose again and again: the revolts of 1211, 1222, 1228 and 1262 were just a prelude; the period 1272–1333 saw a wave of major national uprisings under the feudal Cretan lords – the Chortatzises and the Callergises – rendering Crete at times almost ungovernable. The duke of Crete was killed in an ambush in 1275; Candia was under siege in 1276; the following year pitched and bloody battles were fought on the Mesara plain, Crete’s great fertile crescent; the mountaineers of Sphakia massacred their garrison in 1319; in 1333 the Callergises rose over taxes for a galley fleet.

The Venetians poured money and men into military response, interspersed with unfulfilled promises. Their reprisals were harsh and swift; they burned villages and sacked monasteries; beheaded rebels, put suspects to the torture, exiled women and children to Venice, tore families apart. When they finally captured Leo Callergis in the 1340s, they dropped him in the sea, tied in a sack, following the sombre formula applied in Venice. (‘This night, let the condemned be conducted to the Orfano canal, where his hands bound and his body loaded with a weight, he shall be thrown in by an officer of justice. And let him die there.’) The Republic’s colonial policy remained unbending.

Despite this, Cretan resistance seemed ineradicable. Time and again only clan feuding saved the Venetian project. The areas that rose up and were sacked followed a timeless pattern of resistance. The warrior culture ran uninterrupted down the centuries. The same villages would be burned again by the Turks and yet again in the Second World War. By 1348 Venice had endured 140 years of Cretan defiance. It still had the most shocking revolt to come.

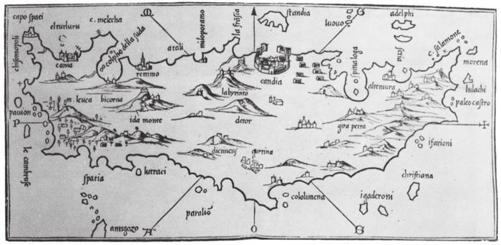

The cost was high. ‘The perfidious revolt of the Cretans monopolises the assets and resources of Venice,’ the senate complained, but whenever it stopped spluttering about the price and contemplated the alternatives it could never bring itself to sail away. Crete was an axiom. If Modon and Coron were the eyes of the Republic, Crete was its hub, ‘the strength and courage of the empire’, the nerve centre of its maritime kingdom, ‘one of the best possessions of the Commune’. The ponderous superlatives ring through the official registers. Nowhere else was the Venetian lion carved more proudly on gateways and harbour walls. Crete was twenty-five sailing days away from the doge’s palace – as far off as Bombay from London to the British Empire of 1900 – but in the imagination of the lagoon, distance was telescoped. Crete loomed large. Misshapen maps of its long low profile, hooked upward slightly at the eastern end, would be endlessly repeated down the long centuries of its occupation; news about Crete on the Rialto was a critical indicator of mercantile fortunes.

Venetian map of Crete

The island was at the crossroads of the Republic’s two great trading routes – those that led to Constantinople and the Black Sea, and those that went on to the spice markets of Syria and Egypt. It was the back station for supplying the crusader ports of the Holy Land; the place for warehousing and trans-shipping goods; for repairing and reprovisioning the merchant galleys; for naval operations throughout the Aegean in times of war. Groggy pilgrims bound for the Holy Land stepped ashore here for a brief respite from the sea. Merchants resold silk and pepper, dodging the intermittent papal bans imposed on trading with the infidel; news was exchanged and bargains struck. After 1381, when the practice was banned in Venice, Crete became the illicit hub of the Republic’s slave trade. In the great barrel-vaulted galley sheds of Candia and Canea, the duchy of Crete kept its own fleet to patrol the coast against pirates, crewed by press-ganged Cretan peasants. Candia itself was a faithful replica of the Venetian world, with its Church of St Mark fronting the ducal palace across a main square, its Franciscan friary, its loggia and its Jewish quarter pressed up against the city walls. From the main thoroughfare, the ruga maestra, running gently downhill to the harbour, the sea was an abiding presence, sometimes whipped into grey fury by the north wind pummelling the breakwater, sometimes calm. From here homesick townsfolk and anxious merchants could watch the ships making the awkward turn into the narrow entrance of Candia’s harbour, and could see them depart again down the sea roads to Cyprus, Alexandria and Beirut; above all to Constantinople.

The maritime trunk route to Constantinople was critical in the map of Venetian trade. It passed via Crete through the scattered islands of the central Aegean – the Archipelago – fragments of rock speckling the surface of the sea. At the centre of these lay the Cyclades, the Circle the Greeks called them, grouped around Delos, once the religious centre of the ancient Hellenic world, now a haven for pirates drawing water from its sacred lake. The islands, separated by a few miles of flat sea, comprised a set of individual kingdoms. Naxos, large and well-watered, famous for its fertile valleys, was the most promising of the group; then volcanic Santorini; Milos famous for obsidian; Seriphos, the best harbour in the Aegean, so rich in iron ore that it confused the compasses of passing ships; pirate-haunted Andros.

Venice had been gifted all these islands by the treaty of 1204, yet it had neither the resources nor the keen economic interest to occupy them as a state enterprise. They were too small and too many to be garrisoned by Venetian forces, yet neither could they be ignored. Their harbours provided shelter in a storm, places to take on fresh water and heave to; unoccupied they represented danger from pirates, threatening the seaways north. With a keen eye to cost–benefit analysis, the Republic threw them open to private venture. Some time around 1205, Marco Sanudo, nephew of Enrico Dandolo, resigned his position as a judge in Constantinople, equipped eight galleys with the support of other enterprising nobles, and sailed forth to carve out his own private kingdom in the Cyclades. He was determined to do or die, not for the glory of the Republic, but for his own cause. Finding the castle at Naxos – the jewel of the central Aegean – occupied by Genoese pirates, he resolved that there would be no retreat. He burned his boats, besieged the pirates for five weeks, ousted them, and declared himself the Duke of Naxos. Within a decade the Cyclades had morphed into separate micro-kingdoms, property of a swarm of aristocratic adventurers, keen for the individual glory on which Venice tended to frown. Marino Dandolo, another nephew of the old doge, held Andros, the Ghisi brothers Tinos and Mykonos, the Barozzi occupied Santorini. Some possessions were doled out whimsically; Marco Venier was granted Kythera, which the Italians called Cerigo, the reputed birthplace of Venus, on the basis of the similarity of names. In each place, the owners constructed castles out of ransacked Greek temples and carved their coats of arms above the door, maintained miniature navies with which they fought each other, built Catholic churches and imported Venetian priests to chant the Latin rite.

An exotic hybrid world grew up in the central Aegean. The majority of the Greeks remained loyal to their Orthodox faith but generally tolerated their new overlords; the Venetian adventurers at least provided some measure of protection against the scourge of piracy, which ravaged the islands of the sea. Despite the prospect of a gold rush which the opening up of the Archipelago seemed to create, the islands contained precious little gold.

The saga of the Venetian Aegean was colourful, violent and, in places, surprisingly long-lasting. The duchy of Naxos did not expire until 1566; the most northern island of the group, Tinos, remained faithful to Venice until 1715. The Republic, however, was to find these freebooting duchies not always to its liking. Marco Sanudo, conqueror of Naxos, lived the life of a charmed adventurer, seeking advantage where he could. He helped suppress a rebellion on Crete, but finding the rewards not forthcoming, changed sides and made cause with the Cretan rebels until he was chased back to Naxos. Undeterred, he ill-advisedly attacked Smyrna, where he was captured by the emperor of Nice; his charm was such that he managed to exchange a dungeon for the hand of the emperor’s sister. The Ghisi, at least, were loyal to the Republic in the nearby fortress of Mykonos. They burned a large candle in their island church on St Mark’s day and sang the saint’s praise. More often, the dukes of the Archipelago launched their tiny fleets across the summer seas and fought petty wars. The Cyclades became a zone of intermittent privatised battle, and its lords were by turns quarrelsome, treacherous and mad. Some were ruled by absentee landlords on Crete; Andros from a Venetian palazzo; Seriphos by the unspeakable Nicolo Adoldo, given to inviting prominent citizens of the island to dinner, then hurling them from the castle windows when they refused his demands for cash. When the crescendo of complaints grew too loud Venice was forced to intervene. Adoldo was banished from Seriphos for ever and languished for a while in a Venetian gaol. But Venice tended to be pragmatic in these matters – Adoldo was piously buried in the church he endowed in the city; it winked at the murder of the last Sanudo to rule Naxos by a usurper more favourable to itself. Nor was it averse to direct intervention. When an heiress to the duchy of Naxos took a fancy to a Genoese nobleman, she was abducted to Crete and ‘persuaded’ to marry a more suitable Venetian lord. This strategy of occupation by proxy had its drawbacks – and in time Venice would be forced to accept direct ownership of many of these places – but at least the petty lordlings of the Aegean damped down the level of piracy and ensured the merchant fleets a more steady passage through the ambush zones of the Archipelago.

Beyond it all lay Constantinople. When the Venetian fleet made its way up the Dardanelles in the summer of 1203 and gazed up at the sea walls of the city, they were confronted with a daunting and hostile bastion. After 1204, the city was Venice’s second home. Venetian priests sang the Latin rites in the great mosaic church of Hagia Sophia; Venetian ships tied up securely at their own wharfs in the Golden Horn, unloading goods into tax-free warehouses. The Republic’s erstwhile competitors, the Genoese and the Pisans, with whom it had brawled repeatedly under the wary gaze of the Byzantine emperors, were barred from the city’s trade. And, for the first time, Venetian ships also had the freedom to pass up the straits of the Bosphorus into the Black Sea and seek new points of contact with the furthest Orient. Thousands of Venetians flooded back into the city to trade and live. So powerful was the attraction of Constantinople, that one doge, Jacopo Tiepolo, for a time podesta (mayor) there, was said to have proposed moving the centre of Venetian government to the city. Venice, once the puny satellite of the Byzantine Empire, idly contemplated replacing it. And the steady, if hard-fought, consolidation of its colonies and bases across the eastern Mediterranean promised to turn the sea into a Venetian lake. Its merchants were everywhere. Tiepolo established trading agreements with Alexandria, Beirut, Aleppo and Rhodes. He articulated a consistent policy and a continuity of effort that would last for hundreds of years. Venetian objectives remained frighteningly consistent – to secure trading opportunities on the most advantageous terms. The means, however, were endlessly flexible. The Venetians were opportunists born for the bargain, ready to sail wherever the current would run.

Destiny lay in the East, in its spices, its silks, its marble pillars and its jewelled icons, and the riches of the Orient flowed back, not only into the coffers of Venetian merchants, stored in the barred ground-floor warehouses of their great palazzos fronting the Grand Canal, but also into the visual imagery of the city. The mosaicists who decorated the Church of St Mark in the thirteenth century imaged the biblical world of the Levant. They reproduced the lighthouse from Alexandria; camels with tasselled reins; merchants leading Joseph into Egypt. An oriental note also starts to pervade the grand architecture of the city.

*

By the time that Renier Zeno became doge in 1253, Easter was celebrated with the splendour of Byzantine ritual. The doge walked in solemn procession the short distance from the ducal palace to the Church of St Mark. He was preceded by eight men holding banners of silk and gold bearing the saint’s image; then two maidens, one carrying the doge’s chair, the other its golden cushions, six musicians with silver trumpets, two with cymbals of pure silver, then a priest carrying a huge cross of gold and silver, embedded with precious stones, another an ornate gospel; twenty-two chaplains of St Mark’s in golden copes followed, singing psalms, and then the doge himself walking beneath the ritual umbrella of gold cloth, accompanied by the city’s primate and the priest who would sing the mass. The doge, looking for all the world like a Byzantine emperor, wore cloth of gold and a crown of jewelled gold and carried a large candle, and behind came a noble carrying the ducal sword, then all the other nobles and men of distinction.

The procession of a doge

As they processed along the facade of the church, past the porphyry columns taken from crusader Acre and those plundered from Constantinople, it was as if Venice had stolen not only the marble, icons and pillars of Constantinople, but its imperial imagery, its love of ceremonial, its soul. In the submarine gloom of the mother church, Easter was celebrated with words that linked sacred and profane, the risen Christ and the Venetian Stato da Mar: ‘Christ conquers!’ went up the cry. ‘Christ reigns! Christ rules! To our lord Renier Zeno, illustrious doge of Venice, Dalmatia and Croatia, and lord of a quarter and half a quarter of the empire of Romania, salvation, honour, life and victory! O, St Mark, lend him aid!’

The events of 1204 amplified Venice’s sense of itself. A growing assumption of imperial grandeur began to possess the little Republic, as if in the shimmering reflection of the spring canals, Venice was morphing into Constantinople.

*

The acclamation of the Stato da Mar would be followed a few weeks later each year by a claim to ownership of the sea itself at another great ceremony: the Senza, on Ascension Day. When Doge Orseolo had departed from the lagoon in the year 1000, this had been a simple blessing. After 1204, it became an increasingly elaborate expression of the city’s sense of mystical union with the sea. The doge, ermine-robed and wearing the corno, the pointed hat that symbolised the majesty of the Republic, was piped aboard his ceremonial barge at the quay in front of his palace. Nothing expressed the city’s maritime pride so richly as the Bucintoro, the Golden Boat. This majestic double-decker vessel, ornately gilded and painted with heraldic lions and sea creatures, covered by a crimson canopy and rowed by 168 men, pulled away from the quay. Golden oars dashed the waters of the lagoon. In the prow a figurehead representing justice held aloft a set of scales and a raised sword. The swallow-tailed banner of St Mark billowed from the masthead. Cannon fire crashed; pipes shrilled; drums beat a rapt tattoo. Accompanied by an armada of gondolas and sailing boats, the Bucintoro rowed out into the mouth of the Adriatic. Here the bishop uttered the ritual supplication: ‘Grant, O Lord, that for us and all who sail thereon, the sea may be calm and quiet,’ and the doge took a golden wedding ring from his finger and tossed it into the depths with the time-honoured words: ‘We wed thee, O Sea, in token of our true and perpetual dominion over thee.’

Despite the rhetoric, the sea which Venice mythologised, and the wealth that it carried, would prove harder won. The Genoese, excluded from easy access to rich trading zones, were snapping continuously at Venice’s heels. They waged an unofficial war of piracy against their maritime rivals. Three years before Doge Renier Zeno walked in the solemn Easter procession, an incident occurred in the crusader port of Acre on the shores of Syria: a Genoese citizen was killed by a Venetian. Three years later, the Mongols sacked Baghdad. In the aftermath of these disconnected events the two maritime republics would be drawn into a long-running contest for Mediterranean trade, which would lead them both to immense wealth and the edge of ruin. The arena would stretch from the steppes of Asia to the harbours of the Levant. It would encompass the Black Sea, the Nile Delta, the Adriatic, the Balearic Islands and the shores of Greece. Brawls would take place as far away as London and the streets of Bruges. Along the way all the peoples of the eastern Mediterranean would be caught up in its slipstream: the Byzantines, the Hungarians, rival Italian city states and the towns of the Dalmatian coast, the Mamluks of Egypt and the Ottoman Turks – all became entwined in the contest for their own advantage or defence. It would last 150 years.