ILLUSTRATIONS

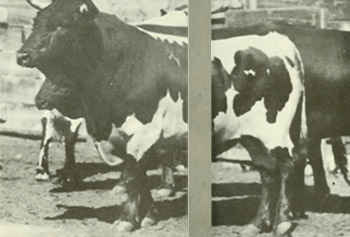

THE SEED BULL

At twenty-two years the horns are splintered; the eyes are slow and all the weight has gone forward and away from where eight hundred and twenty-two sons came from to the ring so that in the end the hind quarters are light as a calf's but all the rest is built into the bull's own monument.

THE OX

While here we have the ox built for beef and for service who might have been president with that face if he had started in some other line of work. He differs from the fighting bull in this, as well as in his general shape; his hoofs are large and broad, his tail is thick and the hairs are flaxy, not silky; he is built high instead of low and there is no hump of muscle that runs from just behind his horns until the middle of his back. He may work hard all his life or he may be made into beef early in his career but he will never kill a horse. Nor will he ever want to. Hail to the useful ox; a friend and contemporary of man.

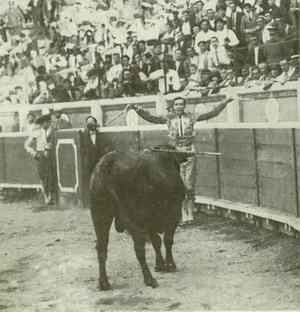

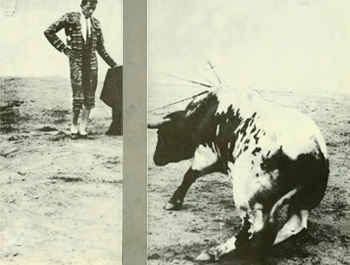

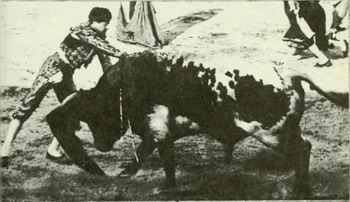

TWO FIGHTING BULLS

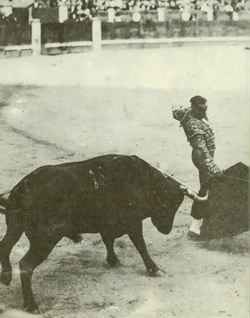

The hump of muscle in the neck rises in a crest when the bull is disturbed. It is his tossing muscle and when the bull carries his head as high as this one in the picture a man could not reach over the horns with a sword. This muscle must be tired for the man to kill the bull properly and it is in the process of tiring this muscle so that a man may kill him by putting a sword in from in front high up between the bull's shoulder blades that the bullfight consists.

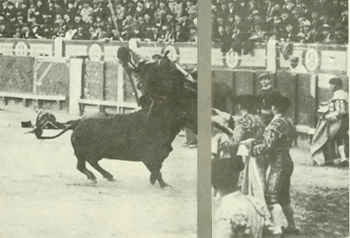

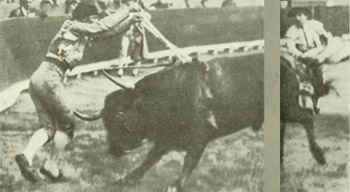

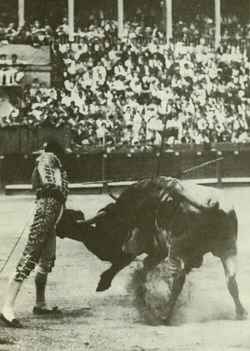

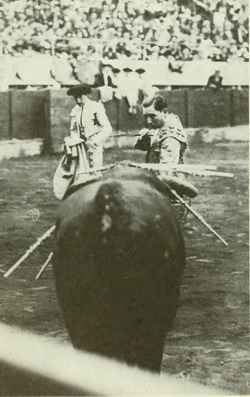

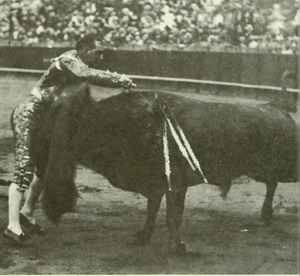

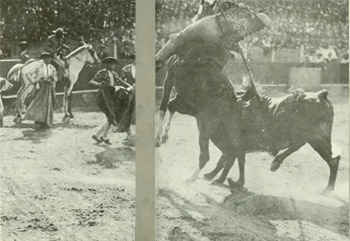

Zurito, from Cordoba, one of the greatest picadors who ever lived, shooting the stick a little back of where it should go, having let the bull get the horn in so he may be well pegged. The style is perfect, the execution is cynical, and the horse, who will be dead very shortly (if you look closely you may assure yourself of this), is not panicky because those knees have convinced him that he is being properly ridden. The horses, incidentally, mostly come from the United States where they are bought at the St. Louis and Chicago markets at five dollars or less a head and shipped through Newport News, a shipload at a time, to Spain. The bull is rather cowardly, otherwise Zurito would not have thrown his hat, seen on the ground, to provoke a charge. Knowing the charges will be few may account for him pegging the bull further back than would be necessary ordinarily.

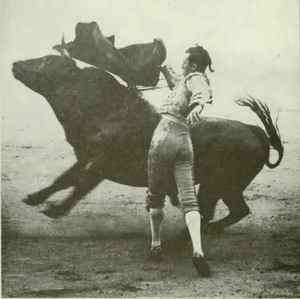

Veneno, killed in the Madrid ring, pic-ing a brave bull, leaning forward onto the stick, the matadors (standing on the right) watching to see where and how the picador will fall and how the bull will turn since they must take him out and away with the capes.

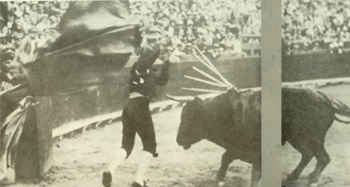

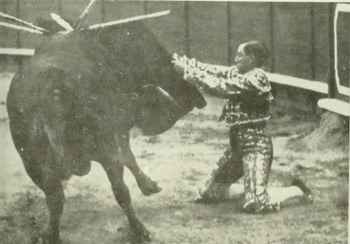

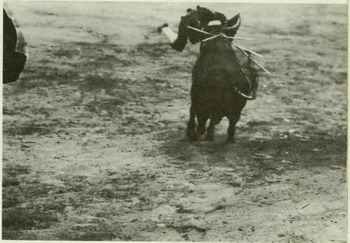

This is what happens when the saddle girth breaks and the picador falls onto the horns. Chicuelo, the matador whose face is partly hidden by the hat, seems a little late in starting in but photographs are very tricky and the fact the picador's hat is still on shows he has just arrived on the horns, which are unusually short. Only the right horn has penetrated. The other matador is Juan Anllo, Nacional II, and the chances are that he will make the quite although if the man falls from the horn when tossed and the bull sees the horse before his horn finds the man the horse will make the quite.

Here every one is coming in to make the quite; even El Gallo, the furthest on the left whose face shows that he does not like the looks of things at all. The bull, trying to gore too fast, is bumping with his nose.

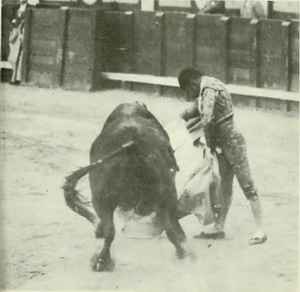

Veronica by Juan Belmonte. Having taken the bull out away from the fallen picador the matador passes him with the cape.

Veronica to the right made by Gitanillo de Triana. This is the second movement in the process of passing the bull by veronicas.

Veronica to the left by Enrique Torres. This is the third movement in passing a bull by veronicas and the three matadors shown making the passes are, with the addition of Felix Rodriguez, the finest artists with the cape the ring has known. Belmonte has not the complete suavity and the low, slow swing of the other three but his is the original style on which they have improved.

Gathering the cape toward him at the end of a series of veronicas to wind the bull around him like a belt, his right leg pushed toward the bull in that bent slant, which will be copied but never made truly until another genius comes in the same twisted body—the media veronica of Juan Belmonte. This pass is the end of a series of veronicas and serves to fix the bull in place and allow the man to walk away.

JUAN BELMONTE

Cagancho sculpturing with the cape. Finishing a series of veronicas with a rebolera, he has turned the bull so short that he has brought him to his knees.

The gaonera as performed by its inventor, Rodolfo Gaona.

BULLS FIGHTING ON THE RANGE AT COLMENAR

BULLS IN THE CORRAL

Five sons of Diano the seed bull

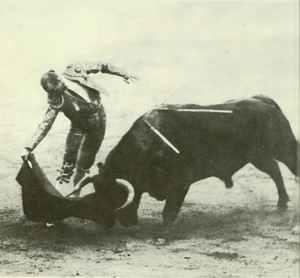

Vicente Barrera in a pase de pecho. This picture and the one below show the basis of the emotion in bull fighting. The emotion is given by the closeness with which the matador brings the bull past his body and it is prolonged by the slowness with which he can execute the pass.

This is Vicente Barrera in the same pass as in the photograph above except that here instead of letting the horn go by his chest he has pulled away prudently so that with the danger removed man and bull do not form one group but are separate entities held together neither by emotion nor by plastic line. A position which would be artistically correct becomes ridiculous without the danger of the horns and the necessary bulk of the bull to give it dignity.

Grace and the lack of it in the ring are in this picture of Cagancho and the following one of Nicanor Villalta performing the same pass, an ayudado por alto, in their respective fashions.

Nicanor Villalta, in the pass Cagancho has made in the photograph above. Villalta can be much more anti-esthetic than this but this is a fair example of his praying-mantis manner.

Villalta kills though in a way no gypsy ever killed and it would he unfair to show how silly he looks with his feet apart and not show him leaning in after the sword.

While when he gets his feet together he will do things like this that you see here; the bull is coming by his legs and as you watch he will spin with him so close the blood from the bull's shoulder will come off onto Villalta's belly. There is great demand for this and only Nicanor can do it.

Here you have him spinning and if there is no blood on his belly afterwards you ought to get your money back.

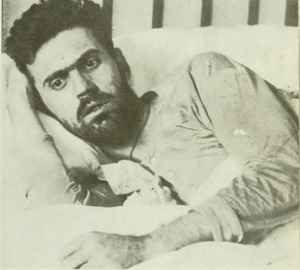

MANUEL GARCIA, MAERA

The year before he died

Maera in a pair of banderillas. Notice how the arms are raised and how straight the body is held. The straighter the body and the higher the arms the closer the bull's horn can come to the man.

Maera citing the bull for the second of four pairs of banderillas he placed at Pamplona in 1924; citing for each pair from such an increasingly dangerous and seemingly impossible terrain that after the second pair the audience were all shouting together "No! No! No! No!" begging him not to take such risks. He placed all four pairs perfectly in the manner and terrain that he chose, performed a brilliant faena and killed the bull as well as a bull could be killed. He had not been to bed the night before and had taken part in the amateur fight at seven o'clock that same morning.

Maera in his characteristic right-handed pass made in the manner of a pase de pecho.

Ignacio Sanchez Mejias, Maera's only rival as a banderillero in difficult and impossible terrains, placing a pair and letting the bull's horn come so close that it is ripping the gold embroidery from his right trouser leg.

Ignacio Sanchez Mejias cheating in the placing of a pair of banderillas through having a number of capes flopping to take the bull away from the man as he places the sticks. Note, however, how well all the banderillas are placed together.

The beginning of the faena. Luis Freg in the pase de la muerte in Madrid.

The end of the faena. Luis Freg in the hospital with a cornada in his chest. Note the scars on the right leg, the scar in the left armpit, and the unplaited lock of hair, that when braided makes the pigtail that was formerly the caste mark of a bullfighter.

Rafael Gomez y Ortega, called El Gallo, standing in the entrance to the Madrid ring with his young brother, José, called Joselito or Gallito, at the start of Joselito's career as a matador. El Gallo is on the left, Joselito beside him. Fourth from the left is Enrique Berenguet, called Blanquet, the confidential banderillero of Joselito. The matador on the right is Paco Madrid of Malaga.

Joselito in a pase natural at the start of his career. Note how, without any contortions, with complete naturalness, with no cork-screwing or faking, he is passing the horn past his belly; bringing the bull around controlled by the swinging end of the cloth that the man is keeping before his far eve.

Joselito, at eighteen, watching a Miura bull that he has killed swaying on his legs before going over on his back, four legs in the air.

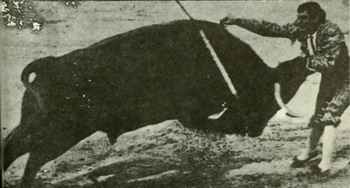

Joselito working with a difficult bull, provoking the charge with his leg; then doubling the bull on himself with the muleta, making him attempt to turn in a shorter space than his own length to tire him.

Joselito at the height of his career, working close, dominating the bull with absolute security, knowing just how much swing of the cloth will move him, controlled a step at a time, and how much more will provoke the full charge. His intelligence and security and the closeness with which he worked made all the bulls look easy to handle. Blanquet, standing by the white-marked burladero, knowing as much about bulls as Joselito, is the only one in all the audience who looks worried.

Joselito the spring he was killed, fat and out of condition after a winter in Lima, Peru, citing an uncertain bull to charge. The bull is slow to start and Joselito, reluctant to rise from his knees and admit his proposal to pass the bull with both knees on the ground was a failure, has just taken out his pocket handkerchief and thrown it at the bull to start him.

The bull comes (the handkerchief still shows on the ground) and Joselito passes him with the muleta without rising from his knees or having to sway back, having calculated exactly the angle the bull will take in his charge.

Joselito taking a bull out a step at a time from the querencia or position he has taken by the barrera; talking to the bull, working on the eye furthest away from the man with the end of the cloth that he imparts a swinging, flicking motion to with his wrist; exposing his own body to give the bull confidence that there is something to charge and yet keeping the animal's main point of vision on the cloth and controlling his impulse to charge with that wrist movement. A brave bull is easy to work with if the man is brave and technically sound; it is the cowardly bull and the uncertain bull that call for most intelligent and careful handling since they will charge as fast as the brave bull but there is no way of knowing when the charge may come.

Here are the naturals of Joselito and Belmonte; the touchstones of their art. Joselito, below, is healthy, sound, natural, his physique and knowledge enabling him to keep the bull well controlled in the muleta. Belmonte, above, is natural in that there is no distortion of his body by himself, but he takes the bull from a more dangerous angle, he emphasizes his peril at the same time as his domination and he has a sinister delicacy of movement that Joselito lacks.

JOSELITO DEAD

JUAN BELMONTE

LAST VIEW OF JUAN BELMONTE

FIRST VIEW OF CHICUELO

CHICUELO

Who could do this

CHICUELO

Who hated to kill

CHICUELO

Of the disasters

AFRAID OF THIS

Opening a cornada in the Madrid infirmary

AFRAID OF THIS

Valencia II, called Chato, with a cornada in the right thigh.

AND OF THIS

Manuel Granero killed in the Madrid ring

AND OF THIS

Granero dead in the infirmary. Only two in the crowd are thinking about Granero. The others are all intent on how they will look in the photograph.

AND OF THIS

Vicente Pastor killing in the ring at Burgos. The horn has caught him as he put in the sword because the wind has blown the muleta up and toward the man.

AND OF THIS

After the corada. Varelito in the hospital

AND OF THESE

Bull of Vicente Martinez that went alive out of the Madrid ring in 1923 when Chicuelo was unable to kill him.

These took his place. Manolo Bienvenida, Domingo Ortega and Marcial Lalanda making the paseo in the ring at Aranjuez. Ortega when this photograph was taken was still an unknown novillero and acted as sobresaliente or substitute matador for the other two.

Marcial Lalanda making the quite of the mariposa or butterfly. Moving backward across the ring, the folds of the cape swing lightly. It takes great skill and knowledge of bulls to do properly or at all.

Marcial Lalanda in a cambio de rodillas made when the bull first comes into the ring.

Marcial Lalanda, most scientific and able of present fighters, watching the bull go down after an estocade.

The highly paid Cagancho often kills like this from cowardice while in Navarra amateurs do this for fun.

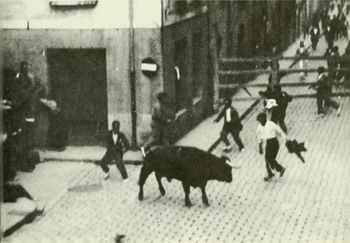

AMATEUR FIGHT IN PAMPLONA

Sidney Franklin killing on the day of his début in Sevilla and below the same Franklin making a veronica in the ring at Cadiz.

GOOD AND BAD KILLING

Above, Varelito has gone in over the horn, kept the bull's head down as he crossed with his left hand guiding the bull after the muleta and is coming out with the sword in and the bull already dead from the thrust.

Below, Manolo Bienvenida is coming out before he has ever gone in and is stabbing at the bull in passing without ever bringing his body within range of the horn.

Zurito killing—see how the man's whole body will pass over the horn, the sword seems going in an inch at a time—the bull's front legs are doubling under him.

Luis Freg killing—his sword hand tight up against the bull—the bull's eye controlled by the swing of the cloth at the tip of the muleta.

El Espartero killing—both the bull's front legs are off the ground—notice how he is crossing with the left hand.

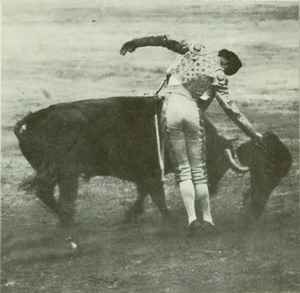

What happens when the bull raises his head from the muleta when the sword is in. The horn is lifting Varelito by the neck. No man going in to kill can be certain the bull may not raise his head from the cloth while the man's body is passing the horn no matter how well controlled the muleta may be. It is this moment that gives the bull his chance at the man and it is when the man avoids this moment that he is said to assassinate the bull rather than to kill him according to rule.

This, for movement, is Felix Rodriguez in a pase natural on a fast charging bull.

This for instruction, with a certain amount of movement still, is a picador ruining a bull by pic-ing him in the ribs instead of placing the pic in the hump of muscle over his neck and shoulders.

This, to remove all tragedy, is El Gallo, dedicating the last bull of his life as a bullfighter. The story is in the text.

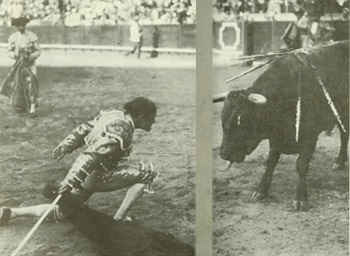

Four of the type of incidents El Gallo avoided so assiduously while fighting bulls for thirty years as a full matador.

Half-bred bull killed in an amateur fight or capea near Madrid but not without, first, having wet his left horn.

The amateur bullfight is as unorganized as a riot and all results are uncertain, bulls or men may be killed; it is all chance and the temper of the populace. The formal bullfight is a commercial spectacle built on the planned and ordered death of the bull and that is its end. Horses are killed incidentally. Men are killed accidentally and in the case of full matadors, rarely. All are wounded; many of them severely and often. But in a perfect bullfight no men are wounded nor killed and six bulls are put to death in a formal and ordered manner by men who expose themselves to the maximum of danger over which their ability and knowledge will allow them to triumph without casualties. In a perfect bullfight, it may be admitted frankly, some horses will be killed as well as the bulls since the power of the bull will allow him to reach the horse sometimes even though the picadors were completely skillful and honorable— which they are not. But the death of the horses in the ring is an unavoidable accident and affords pleasure to no one connected with or viewing the fight except the bull who derives supreme satisfaction from it. The only practical good the death of the horse gives is in showing the spectator the danger the man is constantly exposed to and keeping him reminded that the spectacle, which the grace and skill of the men engaged in makes him take lightly, or for granted, is one of great physical peril. Writers on the peninsula who tell of the public applauding the death of the horses in the ring are wrong. The public is applauding the force and bravery of the bull which has killed those horses, not their death which is incidental and, to the public, unimportant. The writer is looking at the horses and the public is looking at the bull. It is the lack of understanding of this view-point in the public which has made the bullfight unexplainable to non-Spaniards.

And finally El Gallo in one of the series of delicate formal compositions that the happier part of his life in the ring consisted of. The bull, as he should be, is dead. The man, as he should be, is alive and with a tendency to smile.