23

About noon on Veterans Day, Wednesday, November 11, the president and his wife, Michelle, stepped out into a cold rain at Arlington Cemetery. They walked around Section 60, where the dead from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars are buried. One writer christened it “the saddest acre in America.” Obama moved down the aisles of small white headstones to greet the relatives and friends of those lost in battle. Heavy raindrops gathered in his hair, on his face, and on his black overcoat. New graves were being dug in the damp earth.

Pentagon spokesman Geoff Morrell often worked with televisions blaring in the background, watching the ambient screens as a driver might scan the road for oncoming traffic. He was poised to respond to the slightest departure from Gates’s orders that the military lie low during the review.

Around 2 P.M. on Veterans Day, Morrell heard CNN announce an exclusive interview with General Petraeus. No one from the Pentagon or military was to go on television, not even for helping an old lady cross the street.

“I want you to see the humanity in a leader who lives his commitment to his troops,” said CNN anchor Kyra Phillips. “And because of that commitment, one soldier lives today.”

The camera showed Dave Petraeus in the White House briefing room. Whoa. Hold up. No one had told Morrell about this. Could it have been previously taped? Nope, this was a live feed. Right from inside the West Wing, right in the middle of the strategy review.

Petraeus spoke about First Lieutenant Brian Brennan, who had barely survived when his Humvee tripped a 44-pound roadside bomb in Afghanistan a year and a half before. The explosion shredded his legs, which were both amputated, and left him comatose with a brain injury at Walter Reed. On July 4, 2008, Petraeus had visited Brennan. His body lay motionless on the hospital bed, his eyes open but unable to register those around him. And that was when Petraeus—in the glowing words of the CNN anchor—did something “no family member or doctor could,” something “miraculous.”

Brennan had served in the 506th Infantry Regiment, the unit made legendary as the “Band of Brothers” who parachuted into Normandy on D-Day in World War II. Petraeus reminded Brennan of the regiment’s motto, “Currahee.” There was a brief flicker of life from the soldier. Petraeus decided to try again, along with his sergeant major, counting to three and then shouting, “Currahee!”

Like Lazarus, the young soldier awoke. His head and thighs pumped in the air after hearing that familiar Cherokee word. “Currahee” meant “stand alone.” Brennan recovered, walked again, and, inspired by General Petraeus, started a foundation to help injured veterans.

The CNN anchor noted that in less than 10 minutes Petraeus would step into the Situation Room for the eighth meeting of Obama’s war council. Would Obama approve the additional 40,000 troops requested for Afghanistan? she asked.

“That’s up to the president, obviously,” said Petraeus, the White House emblem visible over the shoulder of his dress greens. “And again, our job is to provide him our best professional military advice.”

The anchor weighed in with one last question for the general. Would he run for president in 2012? Some Republicans had suggested he would make an outstanding candidate.

“I’ll close it right here, right now in the CNN newsroom,” Petraeus said. “I will remind you of the great country song that used to ask, ‘What about “no” don’t you understand?’”

Morrell was livid. What part of “no” had Petraeus not understood? He was not supposed to be doing interviews with anyone, not about Afghanistan and Pakistan, and definitely not about Oval Office ambitions. The general should have been unmistakably aware of this after his September comments about the need for a counterinsurgency to a Washington Post columnist had enraged the president.

Morrell later phoned Colonel Erik Gunhus, Petraeus’s public affairs officer.

“What the fuck?” he said.

It’s a Veterans Day double-amputee-feel-good-story, Gunhus said.

“You motherfucker,” Morrell shouted into his phone. He could recognize another chapter in Petraeus’s endless campaign of self-promotion. Dave, the miracle worker, heals the sick. And he had chosen to talk about it—from all places—at the White House, moments before a meeting with the president.

“Why didn’t I know about CNN?” Morrell demanded.

But unbeknownst to Morrell, Gunhus was with Petraeus, and he handed his cell phone to the general.

Gunhus should keep you in the loop, Petraeus acknowledged. But perhaps, he continued, the Pentagon should not try to muzzle its Cent-Com commander.

“When are you going to realize I do these things all the time and I know how not to make news?” Petraeus said. “I can help the cause and explain.”

“Sorry I’m late,” Obama said as he walked into the Situation Room for the eighth strategy review meeting. He added sarcastically, “I was busy reading about what we’re doing in The Wall Street Journal.”

The Journal story quoted “a senior military official” who said the president was about to be presented with a new option for 30,000 to 35,000 troops. The article did not reveal that this was the Pentagon’s response to the October 27 memo from Jones. Obama was angry. It was more of the leaking that Gates and Mullen had pledged to stop.

More troubling was that they were still wrestling with the basic questions: What is the mission? What are we trying to do? What are the objectives? For what purpose? Session after session, these questions remained at the heart of it, yet they had not been answered after nearly two months of work. The experienced Obama watchers from the presidential campaign could see that he was very frustrated and, for him, almost on edge.

Admiral Mullen started off with a PowerPoint presentation titled “CJCS Brief to the President, November 11.” The slides made a psychological warfare argument, a primer on the centrality of resolve to show that war was very much a mind game. The cheerleading message emphasized the importance of commitment, which was what they wanted to convey to the Afghans. And while Mullen didn’t say it, showing commitment started at the top with the president. In counterinsurgency, people have to believe they are more secure. This was right out of Petraeus’s playbook—perception often ruled.

“Resolve is a force multiplier,” Mullen said, and would “have a vital psychological impact.”

His brief continued, “Resolve will be a signal to many stakeholders.” Demonstrating it will reduce “Taliban momentum” and “influence how the Afghan people view their future with the government.

“It will impact continued NATO and coalition commitment and it will encourage the Pakistanis to continue their counterinsurgency effort on their side of the border.

“It also has a potential to produce political and diplomatic effects that will drive reintegration and reconciliation and negate any requirement for additional force”—presumably beyond the 40,000—“by creating a sense of inevitability.” Overall this is “a significant opportunity to impact their strategic calculus.”

Jones suggested they were getting somewhere with these discussions.

“Our goal,” he said, implying a consensus, “is to deny the Taliban the ability to threaten to overthrow the Afghan state and provide safe haven to al Qaeda. It is not to defeat or destroy the Taliban. The military objectives will be limited only to levels necessary to attain this goal.”

“I hope we don’t expand this goal,” Biden said.

“We’ve got to deny the Taliban the ability to take over the country,” Gates said.

“To be more specific,” Petraeus said, “we have to deny them access to and the ability to control the major population centers, the production centers and the lines of communications.”

In a more general way, he added, disrupting the Taliban was insufficient. Throwing them off balance was not enough. It sounded temporary. The time when the Afghans could manage security was a long time off. So the goal had to be to deny the Taliban access to the population.

“More than disruption is required,” McChrystal said, agreeing with his boss.

Gates agreed with his generals.

Biden questioned them, Was it really necessary?

“The key,” McChrystal said, “is stopping their momentum and securing sufficient amounts of the population and lines of communication.” His force level option of 40,000, he said, “does not fully resource a counterinsurgency.” The 85,000 force level got closer, but they had agreed that the military just did not have that many troops available.

Petraeus and McChrystal seemed to be pushing hard to migrate the conversation back to “defeating” the Taliban. The principals had already decided against defeating the Taliban in a traditional sense, yet the generals were making the case that disruption was inadequate.

“Let’s see if we can reconcile Joe’s concerns and Dave’s concerns,” the president said.

Gates said it seemed more a drafting problem with the language than a real disagreement. “We want to provide the time and space to stabilize the country and build forces to resist the insurgency.”

Obama stepped in to halt the discussion. “It’s going to be disrupt. And this is my definition of disrupt: to degrade capacity to such an extent that security could be manageable by the ANSF. Disrupt doesn’t mean scatter, it means degrade their capacity.” He preferred the description of securing substantial portions of the population—though not all of it—and the lines of communication.

Biden wondered if it was possible to accommodate the Taliban the same way Hezbollah had been in Lebanon. The extremist party had become part of the democratic process by winning seats in parliament.

“The key point Joe’s trying to make,” Obama said, “and I want to agree with, is we’re not trying to achieve a perfect nation-state here. We don’t have the resources to do that.”

“No one disagrees,” Gates said. “There has to be reintegration, reconciliation. But we just have to define—with precision—the point at which the Taliban threatens the effort.”

McChrystal insisted that they had to secure the major population centers.

“It’ll take 18 to 24 months to know if this is working or not working,” Mullen said. He had added six months to Gates’s 12 to 18 months. “Disruptions are not enough.”

Had Mullen not been listening? No one said anything, but it was a direct contradiction of the president’s declaration that it was “disrupt.” Mullen then reiterated, “We must reverse the momentum.”

The constant refrain about “momentum” was the military’s way of saying they were losing. “The 40,000 is the best opportunity to protect the population,” Mullen added.

“We should have a plan,” Gates said, “that says 18 to 24 months we will begin reducing our forces, thinning them out. And that puts a marker on the wall for the Afghan leaders.”

This was an electric, pivotal moment for the president. Gates had said in 18 to 24 months they would begin reducing or thinning out U.S. forces. That would be the start of the exit strategy that Obama so clearly wanted. But the president pushed further. Why not just commit to 25,000 and then another brigade could be added after that if necessary? “Could we order in two brigades and then go from there? Why does it have to be all in now?”

That had been discussed in Iraq, Gates and Petraeus said. Dribbling them out would just create more news and questions about whether a certain X number of soldiers would be added at various intervals—all creating great expectations, doubt and more headlines, making it look like they were losing and had to ask for more.*

The question, most agreed, was what would send the strongest message to Karzai and create the most leverage?

Biden read some quotes from a cable that had been sent in by Ambassador Eikenberry—including questions about whether Karzai was the right partner and whether 40,000 troops would do much good. These were the arguments Donilon had asked the ambassador to develop.

Eikenberry wrote, “The proposed troop increase will bring vastly increased costs and an indefinite, large-scale U.S. military role in Afghanistan, generating the need for yet-more civilians. An increased U.S. and foreign role in security and governance will increase Afghan dependency, at least in the near-term, and it will deepen the military involvement in a mission that most agree cannot be won solely by military means.”

In a follow-up cable, Eikenberry recommended that instead of approving the 40,000, “the White House could appoint a panel of civilian and military experts to examine the Afghanistan-Pakistan strategy and the full range of options.” The panel would then meet and deliberate through the end of the year.

Petraeus thought it was laughably late in the game for all this. Though these were reasonable concerns, he felt they had all been asked and answered.

Mullen was still livid at Eikenberry and shocked the cables had not been given to McChrystal in advance.

Turning to immediate business, Mullen then laid out a set of options with the new fourth alternative—the hybrid option developed by Biden and Cartwright that the president had insisted the military include. This final presentation of options had been worked out in very close-hold discussions via secure video or secure phone with Gates, Petraeus and McChrystal:

• Force Option 1 was 85,000—this was an impossible number, Mullen said; everyone had agreed forces at that level were not available.

McDonough thought it reflected poorly on the military that Gates, Mullen, Petraeus and McChrystal would put an option before the president two months into the deliberations that they thought was not realistic.

• Force Option 2 was 40,000, which McChrystal and the military felt provided the best opportunity to protect the population.

• The new Force Option 2A was 30,000 to 35,000 in an extended surge of 24 months that Gates had proposed in his October 30 memo. The Wall Street Journal had it right. This included three combat brigades, required a specific appeal to NATO for a fourth brigade, and “accepts additional risk in developing local security forces.” The fourth U.S. brigade from Option 2 would be held in abeyance, allowing Obama to decide on it in December 2010.

• The hybrid option was 20,000, or two brigades, primarily to disrupt the Taliban with counterterrorist strikes and train the Afghan forces. This was the proposal brought from the October 14 war game by Vice Chairman Cartwright, who had worked it up with the Joint Staff at Biden’s request. Mullen presented it without much enthusiasm.

Petraeus was quite exercised. He found the 20,000 option more than disquieting. It was a repudiation of his protect-the-people counterinsurgency. It should not even get serious consideration. Worse, in the desperate search for options this hybrid “throwaway” seemed to be getting some support.

“You start going out tromping around, disrupting the enemy, and you’re making a lot of enemies,” he said. “Because all you’re doing is moving through, trying to kill or capture bad guys who will fade into the woodwork, and then you leave. And so what have you accomplished?” Alienating the population—the opposite of the counterinsurgency goal—would not really result in any damage to the enemy because “there are not targeted operations.”

Petraeus continued, “This is not a stiletto, this is a chainsaw.” And you have the small-unit, quick-reaction forces from the Joint Special Operations Command “that are doing the stiletto operations, very precise, highly enabled, lots of support and enablers and ISR [Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance] and all kinds of intelligence fusion centers supporting them and everything else. These are conventional forces that can’t be enabled anywhere near the same way. There’s just a limit to how many precise targets you have at any one time anyway. And so you’re essentially going out, just trying to put sticks in hornets’ nests and see what happens. But what you do is you just stir things up.

“We can’t use two brigades to disrupt the enemy,” he went on. “We are going to increase the number of JSOC elements and we will have, within them, a small disruption force.”

Petraeus turned back to Mesopotamia.

“We did this in Iraq. We actually used a battalion in Iraq from the 82nd Airborne that was specially trained and enabled and equipped in the summer of 2007, called Task Force Falcon. And it would go out, but it had all the enablers of a JSOC operation. But it would go into an area where we knew there were bad guys, and it would basically flush them out so that the other JSOC forces could then pounce on them. But they were very, very carefully supported operations because you can get in real trouble out there, and you’ve got to have a lot of assets available in case they really end up hitting something big. You could do them at night when you could have AC-130s [gunships] and all of the other enablers that we could bring to bear that the enemy just couldn’t match.” He explained how they could only use a company of several hundred soldiers at a time for these operations.

And that had been done during the really dark days of Iraq in areas that were in the grip of the enemy, where the U.S. could attack without having to worry about protecting the population.

They would adopt a concept like that for Afghanistan, supported by intelligence and other enablers and backup. But a Task Force Falcon kind of operation couldn’t be done with a brigade—which was at least three times the size of a battalion—because of the amount of helicopters and intelligence needed. Petraeus’s bottom line: You can’t do counterterrorism with infantry brigades. He also cited the Poignant Vision war game, which he said showed that 20,000 wouldn’t work. Relying on the war game was highly misleading and a real stretch. It implied there had been some serious, neutral analysis. The war game had actually been a lot of discussion, and the only two people who might have explained this—DNI Blair and General Cartwright—were not there.

“So,” Obama said, “20,000 is not really a viable option?”

That was correct. Gates, Mullen, Petraeus and McChrystal went further, saying the words a commander in chief never wants to hear. If they only got 20,000, they would not be able to accomplish the mission now described by Jones as “denying the Taliban the ability to threaten to overthrow the Afghan state.” Besides, CT was already a component of their strategy. They planned to increase the counterterrorist forces the next summer under a campaign plan for the secret Task Force 714.

“Okay,” Obama said, “if you tell me that we can’t do that, and you war-gamed it, I’ll accept that.”

Later Biden got a report on the war game, and he told the president that the claims made by Mullen and Petraeus were “bullshit.” It was impossible to reach those conclusions that such an exercise could show counterinsurgency plus would not work. Biden thought the president saw through the war game.

In my interview with the president, Obama did not indicate he was aware that the results of the war game had been misrepresented to him. “The decisions that I ultimately made were not based on any particular war game,” he said.

At another point in the meeting, the president asked, “If Stan needs to get to 40,000, why does that all have to come from us? Why can’t part of that come from NATO?”

The military answer was that NATO troops didn’t always have the same capabilities ours had. What was left unsaid was the simple fact that there was an increasing Americanization of the war. Troops from each of the NATO countries operated under their own rules of engagement and had to answer to their own defense ministries, giving McChrystal less control over them than the absolute authority he had over U.S. forces. This disjointed structure violated one of the first principles of war—unity of command.

But some of the proposed 40,000 were going to be used for training and security that NATO troops could handle, Obama noted. “I want to include a NATO brigade as part of the 40,000,” he said.

Petraeus seemed fixated on preserving the third brigade. Gates had already effectively given away the fourth brigade. Now the third was in jeopardy. “Stan needs this brigade in order to be able to plan,” Petraeus said, “to set his plan for the next couple of years.”

Petraeus was thinking in timelines, but so was Obama.

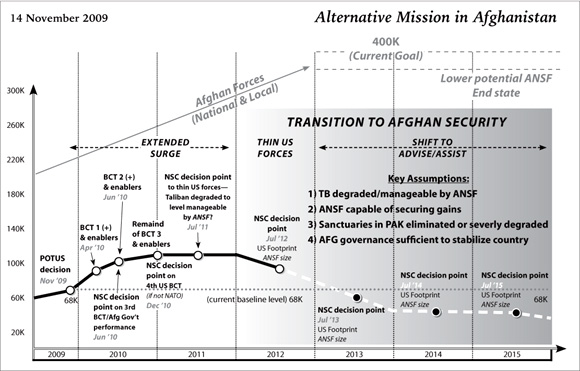

The president held up a green-colored graph labeled “Alternative Mission in Afghanistan” showing the projected deployments like a slow-rising mountain that peaked at 108,000 U.S. troops after the 40,000 were added in the next 15 months. The mountain then gently slid back down to the current 68,000 over six years.

“Six years out from now, we’re just back to where we are now?” said Obama in mild disgust. “This just gets me back to where we are today six years from now. I’m not going to sign on for that.”

It was a clear rebuke to the military, across the board. Two months of work. And the president had only begun.

Earlier, he had had a private talk with Donilon and Lute, who told him the Pentagon wasn’t stretching itself. Here was the glaring contradiction: The military said the situation was so serious that it might fail in 12 months, but they wanted to deploy 40,000 more troops in what amounted to 15 months. The Pentagon and its military leaders could come across as organized, thoughtful and hard-charging, but, Donilon and Lute had told him, they needed to be probed.

At the meeting, Obama said, “Look, here’s the deal. I don’t know why it takes us this long … I don’t know how I’m going to describe this as a surge?”

He turned to Petraeus. “Dave, why does it take so long to get these troops in there? How long did it take in Iraq?”

“We built it from January to June, 2007,” Petraeus answered. So it took six months to move in 30,000 troops and then begin a gradual off-ramp.”

“Why is this going to take longer?” Obama asked. His tone had turned to interrogation.

Petraeus explained the differences between landlocked Afghanistan, where supplies had to be trucked through mountain ranges on limited and dangerous roads, and Iraq, which had better roads and access to a port along the Persian Gulf.

“I know it’s not the same as Iraq,” Obama said. “I know this is a very different country. So I’m not saying it’d be the exact same plan as Iraq, but I am looking for something that is a surge to create the conditions for a transition.” The president was looking to the military to provide much more than a way into Afghanistan. He also wanted to find a way out.

“If we went faster,” Obama continued, “wouldn’t it have a bigger effect on the politics of the country?” He pointed to the slow-rising graph showing the projected addition of force into Afghanistan. “You’ve got to move this to the left. If it’s as grave as we know it is, why are we waiting until 2011 to be at the maximum?”

Obama held the chart and waved it as if it were a piece of damning evidence in a courtroom. “Where we are now,” he said, pointing to the current 68,000, “is above where we were when we came in.” That had been just 35,000. “Five years from now we’re only where we are now,” he said. The chart showed the force level at about 68,000 then. Under this plan he would have more troops in Afghanistan when he left office—whether after one or two terms—than when he took office. And the United States would only get down to 20,000, as he put it, “after my presidency.”

Rhodes passed McDonough a note saying: More troops in Afghanistan in 2016 than when he took office!

Obama was almost fretting. “A six-to-eight-year war at $50 billion a year is not in the national interest of the United States.” That was what was before him. The entire timeline from deployment to drawdown was too much. “Actually,” he continued, “in 18 to 24 months, we need to think about how we can begin thinning out our presence and reducing our troops. This cannot be an open-ended commitment.”

Petraeus then boldly declared that he thought they could get all the troops in by the first half of next year.

The president took another look at Mullen’s four options.

“So let me get this straight, okay?” Obama asked. “You guys just presented me four options, two of which are not realistic”—the 85,000 dream and the 20,000 hybrid. Of the remaining two—the 40,000 and Gates’s 30,000 to 35,000—he noted their numbers were about the same. “That’s not good enough.” And the way the chart presented it, the 30,000 to 35,000 option was really another way to get to the full 40,000 because there would be a decision point for the fourth brigade in a year, December 2010. So 2A is just 2 without the final brigade? he asked.

“Yes,” said McChrystal.

Two and 2A are really the same, Obama said. “So what’s my option? You have essentially given me one option.” He added sternly, “You’re not really giving me any options. We were going to meet here today to talk about three options. I asked for three options at the Joint Chiefs meeting.” That was some 10 days earlier. “You agreed to go back and work those up.”

At one point Mullen said, “No, I think what we’ve tried to do here is present a range of options, but we believe that Stan’s option is the best.”

But, Obama pressed, you haven’t really made them that different.

It was silent in the room, and there was a long pause.

“Well, yes, sir,” Mullen finally replied. He later said, “I didn’t see any other path.”

It was as if the ghosts of the Vietnam and Iraq wars were hovering, trying to replay the history in which the military had virtually dictated the force levels. This was the second lesson from Gordon Goldstein’s book about McGeorge Bundy and Vietnam: “Never Trust the Bureaucracy to Get It Right.”

The president repeated that he wanted the graph moved to the left. Get the forces in faster and out faster. “You tell me that the biggest problem we have now is that the momentum is with the Taliban, and the reason for this resource request is that the momentum is with the Taliban. But you’re not getting these troops into Afghanistan” for more than a year. “I’m not going to make a commitment that leaves my successor with more troops than I inherited in Afghanistan.

“We have a government with a serious dependency issue,” Obama said of Afghanistan. “If I’m Karzai, this looks great to me, because then I don’t have to do anything.

“It’s unacceptable,” he said. He wanted another option.

“Well,” Gates finally said, “Mr. President, I think we owe you that option.”

It never came. I later pressed the president twice about what happened and why. He finally acknowledged that he personally had to help design a new option. “What is fair is that I was involved,” Obama said. “I was more involved in that process than it was probably typical.”

Afterward, Petraeus immediately got on the secure video with his logistics team, which moves troops and supplies in and out of war zones.

“Okay,” he said, addressing them fondly as “Logistics Nation,” his term for the team headed by Major General Ken Dowd, who was the combatant commander’s supply officer. “I’ve just written a check and I need you to help me cash it.”

“Hooah, sir!” Dowd said, using the universal military expression that means anything and everything except no.

Petraeus said that he had told the president they could get all the troops and equipment on the ground in Afghanistan by the first half of 2010. “We really need to drill this absolutely in every respect. Where can we shorten timelines?” It was a matter of squeezing everything.

So it was back to the drawing board for the military as Obama went off on a 10-day trip to Asia. On the way over, he phoned Gates from a secure line on Air Force One.

“Bob, I just want to go through what we talked about,” he said, and repeated the elements of the new option he was looking for.

“That’s what we’re working on,” Gates promised.

Later, Obama expressed his frustration to his top advisers. The military was “really cooking the thing in the direction that they wanted.” Once they got around to dealing with enablers and the flexibility that the military would want, the choice would be between 40,000 and 36,000, he said.

It was laughable. “They are not going to give me a choice.”

What also really set off the president was that the military wanted to leave more than 100,000 troops there for years. “I’m not going to leave this to my successor,” and the military plan “compromises our ability to do anything else. We have things we want to do domestically. We have things we want to do internationally.”

The open-ended, perpetual commitment of force in Afghanistan is wrong for our broader interests, Obama said. First, it would increase the dependency of the Karzai government, which would be happy to have us there forever to do the hard things. Second, it doesn’t address corruption and it reinforces the Taliban’s talking point that we will permanently occupy the country. So, he said, the task of balancing the military imperative with all of this was going to be his.

“If they tell me these are the resources that they really need to break the Taliban’s momentum then we need to do that” in some form. “But I have to figure out a way to make this option aligned with what I feel are the strategic interests that we have in Afghanistan.” And they are limited. He was going to have to begin to map some way out.

Obama indicated that he had wanted the strategic review to be as prolonged as it had been in order to get away from the events of the early fall when the McChrystal assessment had been published and McChrystal had given the London speech. These events had created the appearance that the military was boxing him in. Obama said he wanted his final decision to be based upon his consultation with the military and not something that was forced upon him. He had to get himself and the country out of that box. War could not suck the oxygen out of everything else. Some of it had to do with the nature of wars that had the U.S. fighting local insurgencies. There were going to be no victory dances in the end zone. One of his problems with Bush had been the constant talk of a victory that was not attainable.

Obama had campaigned against Bush’s ideas and approaches. But, Donilon, for one, thought that Obama had perhaps underestimated the extent to which he had inherited George W. Bush’s presidency—the apparatus, personnel and mind-set of war making.

After the November 11 meeting, Mullen and Lute talked privately.

“Mr. Chairman,” Lute said, “the president really wants another option. This is not a wild hair by the VP. This is, he’s serious about this. There’s no question. Look, he really expects a paper here. We’ve got to have this analysis.” Gently he added, “You’re on the hook. The president’s going to call on you.”

Mullen wasn’t acting as if he felt any pressure. Lute was astonished.

Three days later, Mullen and the Joint Chiefs of Staff produced the latest version of the secret graph entitled “Alternative Mission in Afghanistan.”

It was a source of the president’s mounting frustration. Under this revised plan, an imaginary dotted line showed a drawdown beginning—possibly—in 2012, the year he would be running for reelection. The current level of 68,000 would not be reached until the spring of 2013, according to the chart. Then the shift to an “advise/ assist” mission would begin to take place. But according to the chart, it would only happen if four “key assumptions” were realized, none of which the strategy review had suggested were likely. The assumptions were that the Taliban would be degraded to “manageable” by the Afghans, the Afghan security forces would be able to secure the gains from the U.S. surge, the sanctuaries in Pakistan would be “eliminated or severely degraded,” and the Afghan government could stabilize the country.

The chart projected some 30,000 U.S. troops in Afghanistan into 2015. In my interview with the president, I said that based on the chart someone had suggested “No Exit” as the title of this book.

Obama disagreed. “You don’t know the ending,” he said. “Because there is going to come a point in time in which the United States’ combat function in Afghanistan will have ceased.”

The president did not say when that might be.

* At the end of 2006 when Petraeus had been the commander-designate for Iraq he insisted that President Bush make an up-front commitment to send five brigades, saying, “Don’t bother to send me to Iraq if you’re only going to commit to two brigades.”