CHAPTER 6

Abdomen

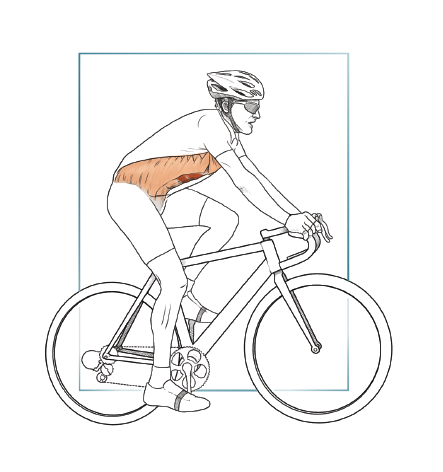

The abdominal muscles often don’t receive enough attention from cyclists, but neglecting these muscles would be a big mistake. The abdominal muscles help establish your core strength, stability, and power. Training these muscles in the gym should be a key element in your weight training program. Strong abdominal muscles are fundamental to your fitness, performance, and overall health.

Low back pain in cyclists often results from the anterior muscles of the abdomen not being strong enough to counter the forceful back muscles. Because cyclists spend so much time leaning forward while in their riding position, they develop an amazingly strong and well-conditioned back. This hypertrophy (building) of the back is necessary and unavoidable when you spend a lot of time on the bike. However, the downside of this development is that it can throw off your spinal balance and skeletal stability.

As mentioned in chapter 5, your vertebrae should stack uniformly, one on top of the next. If your back muscles are pulling on your spine more than your anterior abdominal muscles are, your vertebrae will slowly be pulled out of alignment. If this misalignment progresses, your intervertebral discs may start to protrude. This is often referred to as a “slipped disc,” and anyone who has experienced this unfortunate situation can attest to the high degree of discomfort and pain. This condition can become debilitating and may need to be repaired by a spinal surgeon. Ideally, with good conditioning and training as well as proper back care, you’ll avoid this unpleasant experience. Adequate conditioning of your abdominal muscles needs to be done in the gym, and the core exercises in this chapter will show you proper form and training technique.

Another function of the abdominal muscles is to provide a stable platform for your two large pistons powering the cranks. As your legs rotate through the pedaling motion, your hip joint and pelvis are stabilized by your abdominal and back muscles. The foundation of any structure is fundamental to its stability, and your body is no different. To get the most drive from your legs to the pedals, your core needs to be solid and unwavering. This doesn’t mean that your pelvis is not moving, but rather that your back and abdominal muscles are working in unison to provide the proper pelvic position during your pedal stroke. If your abdominal and back muscles are not locking your pelvis effectively, you will not be able to realize your optimal performance.

Finally, when you’re riding at your limit and trying to suck every molecule of oxygen out of the air, your abdominal muscles will contribute to your maximal ventilatory (breathing) volume. As you strain under the high demands of your ride, your entire body will be working in concert to deliver sustained power to the pedals. Again, this is why conditioning and training your entire body will bring you the best results on the bike.

Abdominal Musculature

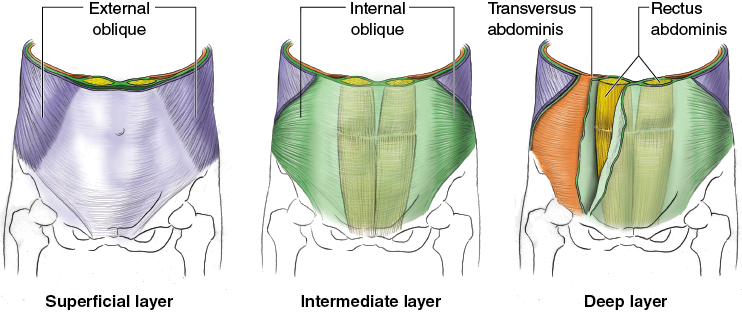

The abdominal muscles are a group of layered muscles that allow your torso to flex forward, rotate, and bend from side to side. In addition to the well-known rectus abdominis muscles (the “six pack”), three other muscles help form your abdominal wall. These muscles are positioned on top of each other, enabling them to efficiently provide the wide range of movement of your trunk. The exercises in this chapter will work all of these muscle groups.

The two side-by-side rectus abdominis muscles are the most visible and forward-facing muscles of the abdomen (see figure 6.1). They extend vertically from the lower margin of the ribs and sternum to the pubic bone of the pelvis. Surrounding these muscles is a tough fibrous material (fascia) called the rectus sheath. The rectus sheath creates a gridlike pattern that tacks down the muscle fibers. This forms both the central vertical demarcation down your abdomen (linea alba) and the horizontal divisions (tendinous inscription) that create the “six pack” appearance. The rectus abdominis muscles flex the torso forward. Working together, the upper muscles pull down on the ribs, and the lower muscles pull up on the pelvis. This performs the crunching motion used in many exercises.

Figure 6.1 Muscles of the abdomen.

The other three muscles of the abdomen are all lateral to the rectus abdominis. The outermost layer is the external oblique muscle. It is angled downward and inward from the ribs toward the linea alba and pelvis. As the muscle passes medially (inward), it forms a tough fibrous sheath called the external oblique aponeurosis. This coalesces into the rectus sheath mentioned previously.

The internal oblique is the middle layer of muscle. It is functionally angled in the opposite direction of the external oblique, running upward and inward from the pelvis toward the linea alba and ribs. The internal oblique also forms a fibrous aponeurosis that combines with the rectus sheath and the aponeurosis of the external oblique.

Contraction of both obliques on one side causes the torso to bend to that side. Simultaneous contraction of the obliques will aid the rectus abdominis in flexion. Bilateral contraction also protects and splints the abdominal wall whenever you’re straining or bearing down (the Valsalva maneuver, or trying to push air out with a closed mouth and nose).

The innermost muscle is the transversus abdominis. As if designed by an engineer to cover all possible movements, the transversus abdominis runs horizontally from the back, ribs, and pelvis to the pubis and rectus sheath. Like the other abdominal muscles, it also forms fascia sheets. The thoracolumbar fascia of the back gives rise to the muscle laterally and medially (toward the center); the fascia contributes to the rectus sheath and abdominal aponeurosis. The primary role of the transversus abdominis is to help with forced expiration and increase intra-abdominal pressure. It also helps stabilize the abdominal wall during periods of high effort and strain.

This chapter provides exercises that will help you develop all your abdominal muscles. Anatomically, there is no upper, middle, and lower abdomen, but to help your focus in the gym, the exercises are divided into various abdominal sections. Although each exercise will work most of your abdominal muscles, certain areas will be under more stress and strain. As you perform each exercise, you should concentrate on those muscles described as “primary” in the exercise description. There is no quick way to achieve strong abdominal muscles—regardless of what some commercials might say! You have to spend time and effort in the gym to develop these important performance-enhancing muscles.

Warm-Up and Stretching

As with all workouts, you need to perform an adequate warm-up before engaging in these strenuous exercises. Spend 10 minutes doing cardio work on the exercise bike, treadmill, or elliptical. After you have elevated your heart rate and generated a sweat, you need to stretch the muscles of your abdomen and torso. Many of the exercise motions found in this chapter can serve as a good warm-up. Remove the resistance and perform the movement of the exercise as described. For the warm-up, you can slightly extend the range of motion compared to when doing the exercise with resistance. Here are two other good stretches:

1. Holding a broomstick across the back of your shoulders, twist at the torso from side to side for 30 to 60 seconds.

2. Stand erect with your feet together and your arms extended vertically above your head. Keeping your arms straight, extend and arch your back, reaching your hands upward and backward. Slowly arch your arms forward and downward, bending at the torso and keeping your legs straight. While keeping your legs straight, attempt to touch your toes. Reverse the motion until you return to your starting position. Repeat the complete range of motion until you feel adequately stretched.

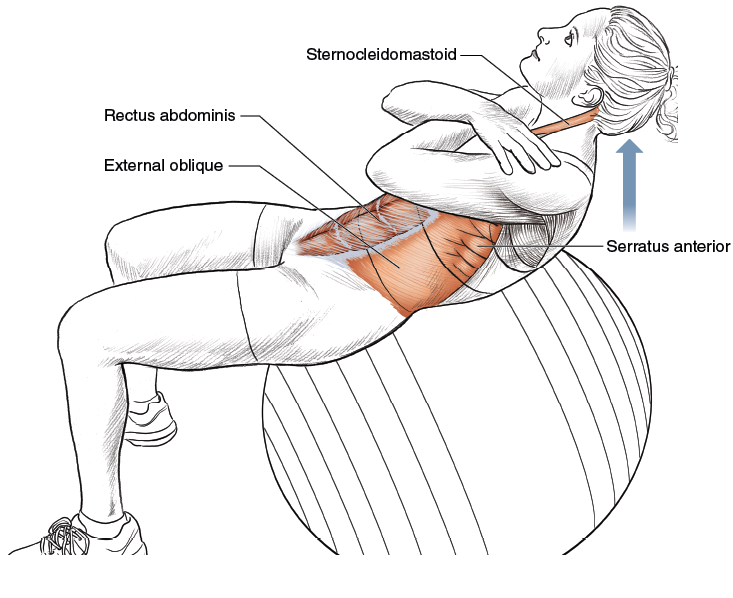

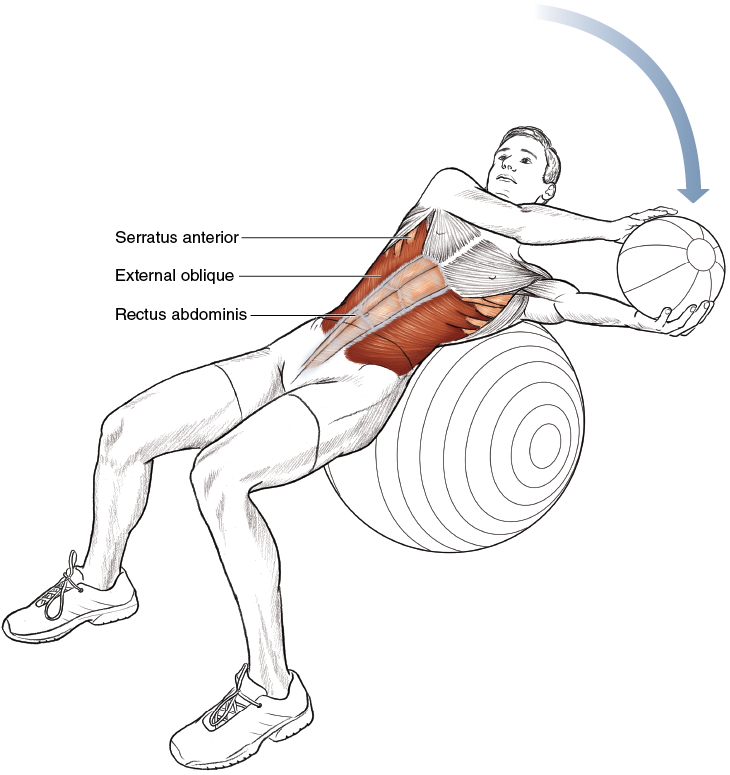

Stability Ball Trunk Lift

Safety Tip

Keep your chin pointed upward toward the ceiling. Curling your chin down toward your chest will put undue strain on your cervical spine.

Execution

1. Place your arms across your chest and rest your lower back on top of a stability ball. Your back and thighs should be horizontal and parallel with the floor. Your knees should be bent at 90 degrees, and your feet should be flat on the floor.

2. Lift your chin and torso upward as far as possible. Concentrate on moving your chin in a straight line toward the ceiling.

3. Pause briefly at your maximal height and then slowly return to the starting position.

4. For added difficulty, you can hold a medicine ball or weight plate with your arms outstretched over your chest throughout the entire motion.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Rectus abdominis (upper)

Secondary: Internal oblique, external oblique, serratus anterior, sternocleidomastoid

Cycling Focus

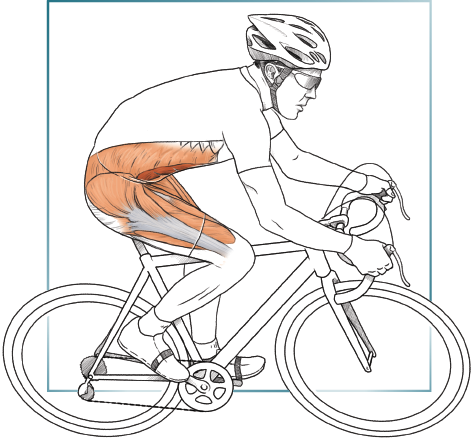

To deliver sustained power when riding your bike on a climb, you need to have a strong core that can handle the torque of your legs as they rotate through your pedal stroke. If you’re delivering optimal power, you’ll be pulling up with one leg while simultaneously crashing down with the other. At the same time, your arms will be pulling back and forth on the handlebars. Your core is the platform between your two sides, and the alternating movement of your legs and arms will naturally work to flex and destabilize your trunk. By maintaining a strong abdomen, you will help ensure that your upper body and pelvis can effectively fight against unnecessary movement. Any unwanted movement of your body or bike will lead to power loss and inefficiency. Even the best professionals only operate at near 27 percent efficiency, so saving your energy wherever possible is critical.

Variation

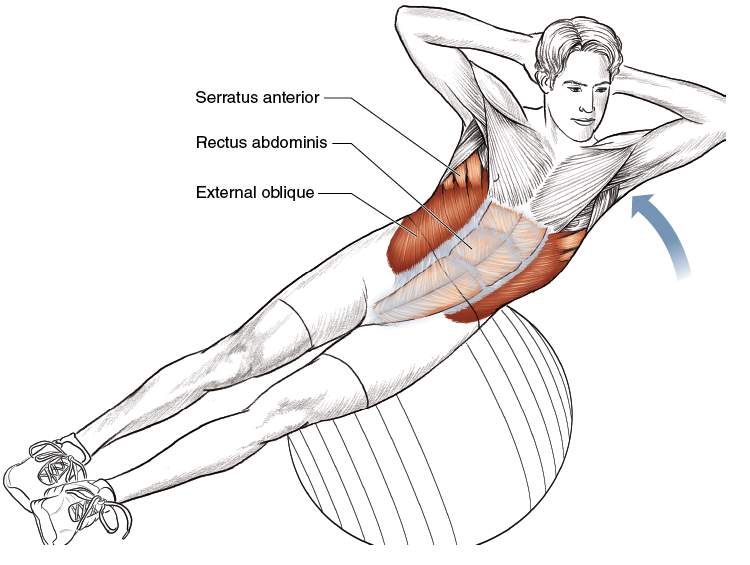

Side-to-Side Trunk Lift

Perform the same exercise, but instead of merely moving up and down, alternate lifting your body from side to side. This will not only work your rectus abdominis but will also focus on your obliques. Again, to increase the difficulty of the exercise, you can hold a medicine ball or weight with outstretched arms above your chest as you lift your trunk.

Stability Ball Pass

Execution

1. Lie on your back with your legs extended. Squeeze a stability ball between your feet, and extend your arms horizontally above your head.

2. Perform a crunch motion, pulling your legs and arms to the vertical position. Your shoulders should come vertically off the floor.

3. Slowly return to the starting position.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Rectus abdominis (upper)

Secondary: External oblique, internal oblique, hip adductors, hip flexors, quadriceps, serratus anterior, sternocleidomastoid

Cycling Focus

The importance of pelvis stability when riding a bike cannot be overemphasized. Whether you’re sprinting, climbing, or time trialing, your legs rely on a strong foundation to enable them to generate their impressive force while rotating the cranks. During a time trial, your body should be still and solid as you slice through the wind in your aerodynamic position. The more power you can deliver to the pedals, the faster you’ll ride. Your abdominal muscles will play a key role in establishing this needed base. The stability ball pass has the advantage of working some of your hip and leg muscles as well as your abdomen. By pushing your feet together to hold the ball, you will work your hip adductors. Good strength in both your adductors and abductors will help smooth your pedal stroke when you’re fatigued or working at maximum capacity.

Rope Crunch

Execution

1. Facing away from the pulley system, kneel on a mat while holding a high pulley rope attachment above your head.

2. Curl your body downward toward the floor. Concentrate on bending at the waist.

3. Slowly return to the upright kneeling position.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Rectus abdominis (upper)

Secondary: External oblique, internal oblique, serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi

Cycling Focus

As previously discussed, the standard cycling position places an immense amount of strain on your back. All the hypertrophy of the back that results from hours of riding will need to be balanced by abdominal muscle training. Rope crunches will help keep your spine in good alignment as well as produce a solid core. The end of this exercise places you in a similar position to being in your drops on the bike. It therefore works the abdominal muscles where needed the most. As you move through the range of motion of this exercise, you should try to feel how it mimics various positions on the bike (hoods, tops, drops, time trialing). This will help train your body’s awareness of position and focus the exercise on areas that need the most stabilization.

Variation

Floor crunch: Lie with your back flat on a mat. Lift your thighs so they are vertical (perpendicular to the floor). Perform a crunching motion, concentrating on lifting your chin and shoulders straight up in the air.

Stability Ball Pike

Execution

1. Get into a push-up position with your shins on top of a stability ball.

2. Lift your waist upward, rolling the ball toward your head as far as possible.

3. Keep your back and legs straight during the entire exercise.

4. Return to the starting position.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Rectus abdominis (middle)

Secondary: External oblique, internal oblique, serratus anterior, hip flexors, quadriceps, triceps

Cycling Focus

This exercise is terrific for cyclists. It works core stability as well as the abdominal muscles, quadriceps, arms, and shoulders. Because the ball can freely roll, you will be forced to use all of your accessory stabilizing muscles to maintain good form. These are the same muscles that will help you with your riding form when you become fatigued. When riding, your key foundation points will be your arms on the handlebars and your feet on the pedals. This exercise trains the same muscles. You’ll be amazed at how tough this exercise is, and you’ll definitely notice your gains once you hit the road. Focus on controlled inhalation and exhalation throughout the entire range of motion. When riding your bike, you must continue controlled breathing even during tough efforts. Without the delivery of new oxygen to the muscles—and the removal of carbon dioxide from the muscles—you’ll soon lose power and the ability to rotate the cranks.

Plank

Execution

1. Using your forearms rather than your hands, get into a standard push-up position.

2. Keep your back straight. Hold the position for 30 seconds to 1 minute.

3. Rest for 30 seconds to 1 minute and then repeat.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Rectus abdominis (middle)

Secondary: External oblique, internal oblique

Cycling Focus

If you have to watch TV, then this is the way to do it! To make good use of your time, you should try this exercise the next time you find yourself in front of the tube. As with the other abdominal exercises, this one helps build a strong foundation on which to base your power when riding. This exercise causes you to splint your abdominal wall. This will help strengthen the respiratory muscles that maximally will deliver oxygen to your lungs when you’re really putting the hammer down. As your fitness improves, you can increase the time that you hold the position.

Variation

Oblique Plank

You can perform this same exercise emphasizing one side at a time. This will further enhance your core stability.

Reverse Crunch

Execution

1. Lie with your back flat on the floor, your arms extended outward, and your knees bent at 90 degrees. Your thighs should be vertical with a 90-degree bend at the hip.

2. Focus on lifting your pelvis upward off the floor and bringing your knees toward your chest. Your lower legs will become vertical and perpendicular to the floor.

3. Slowly lower your legs and pelvis to the starting position.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Rectus abdominis

Secondary: External oblique, internal oblique, transversus abdominis, serratus anterior, quadriceps, hip flexors

Cycling Focus

The reverse crunch focuses on your lower abdominal muscles. This is exactly where you need the most solid foundation during your rides. Your powerful legs need these muscles to remain steadfast during extreme efforts. Imagine being in a two-man breakaway as you near the finish. Each of you rotates through, breaking the wind and trying to keep the pace high. You maintain as aerodynamic a position as possible, and your legs are pulling hard. Luckily, your training helps keep your pelvis stable. As you pull off, you’ll have to quickly recover from your effort before you need to drive on again. This will require forceful blowing off of your carbon dioxide. Your obliques and transversus abdominis will be working overtime to help provide maximal ventilation.

Hanging Knee Raise

Execution

1. Hang from the pull-up bar using a palm-forward grip.

2. Simultaneously lift both knees until your thighs are parallel with the floor.

3. After a brief pause in the up position, slowly lower your legs back down.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Rectus abdominis

Secondary: External oblique, internal oblique, transversus abdominis, hip flexors

Cycling Focus

This exercise not only works your abdominal muscles, but also stretches and decompresses your spine. After long rides, it always feels good to get in the gym and perform this exercise. Sitting on the saddle compresses your spine, and the forward leaning position on the bike can tighten your back muscles. Before and after a set of hanging knee raises, you should hang for a few moments to let the ligaments and muscles get a good stretch. As you lift your legs, you’ll feel the strain on your abdominal muscles. This exercise will give you a great workout to help balance the power of your lower back. You’ll also be training your smaller stabilizers if you keep your body under control during the exercise—no swinging as you lift and lower your legs. In addition, you’ll be working your forearms and grip strength by hanging from the bar. If you have trouble holding on to the bar for the entire set, try using the arm slings. Slip your hand and elbow through the sling and let your body weight rest on the back of your upper arms.

Variation

Alternating hanging knee raise: Instead of raising your legs straight up in front, try doing a set in which you alternate raising your knees to one side and then the other. This will place added emphasis on your oblique muscles.

Stability Ball V

Execution

1. Sit on a large stability ball, placing your hands behind and to the side of your buttocks. Lean your torso back slightly and hold your feet off the ground, keeping your legs straight.

2. Create a “V” with your body by bending at the hips. Keep your knees and torso straight.

3. Slowly bring your torso and legs together, decreasing the angle of the V.

4. Return to the starting position.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Rectus abdominis, hip flexors

Secondary: External oblique, internal oblique, rectus femoris, sternocleidomastoid

Cycling Focus

The stability ball V is a tough exercise. It requires strength, coordination, balance, and focus—all of which will help your riding. Because you keep your legs and torso straight—only bending at the hips—you’ll condition and strengthen the linkage between your upper and lower body. The hip flexors get a great workout, and the power gained from this exercise will be directly applicable to your riding. By using the stability ball, you’ll get a lot of work out of your hips, pelvis, and trunk stabilizers. This will help solidify your skeletal foundation and give you a great platform for delivering optimal power to the pedals.

Variation

Bench V: If you have a difficult time performing the exercise on a stability ball, you can use the same technique while sitting on a flat workout bench. After you master the exercise on a stable platform, you’ll likely be able to move to the stability ball. (Don’t feel bad if you initially have trouble with the stability ball. It’s hard!)

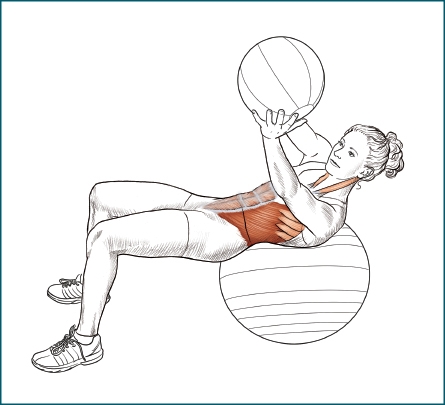

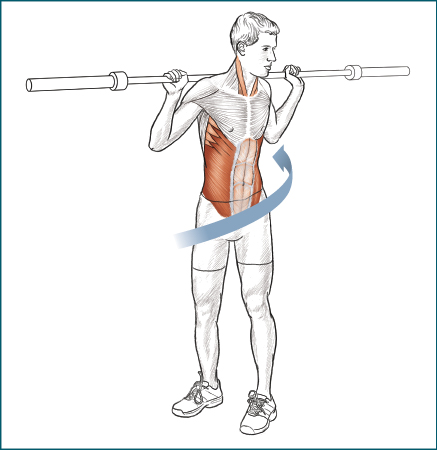

Trunk Twist

Execution

1. Lie with the middle of your back resting on a large stability ball. With extended arms, hold a medicine ball or weight plate vertically above your chest.

2. Keeping your elbows straight, sweep your arms to the left until they are nearly parallel with the ground.

3. Return your arms to the starting (vertical) position and repeat the movement to the other side.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Internal oblique, external oblique

Secondary: Rectus abdominis, serratus anterior, sternocleidomastoid

Cycling Focus

If you watch professional riders climb out of the saddle, you’ll notice how still they keep their upper body. Even when they are going all out and powerfully turning the cranks, they maintain a calm composure. The obliques trained in the trunk twist exercise are key in providing that stability. With each turn of the pedal, the bike wants to rock from side to side. To prevent this movement, your internal and external obliques, transversus abdominis, and rectus abdominis will all be firing to lock down your torso. When the going gets rough, these muscles will also help you achieve your maximum respiratory effort to keep the engine churning.

Variation

Broomstick Twist

The broomstick twist is a great exercise for increasing flexibility and working out any kinks or tight spots in your torso. You can use a simple broomstick or a weighted bar (these bars are found in many gyms). Focus on complete range of motion.

Oblique Crunch

Execution

1. Lie with your side resting on a large stability ball, your hands on the sides of your head, and your elbows pulled back.

2. Lower your trunk downward, wrapping your side around the ball.

3. Slowly raise your trunk by lifting your upward-facing elbow toward the sky.

4. After the set, repeat on the other side.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Internal oblique, external oblique

Secondary: Rectus abdominis, serratus anterior

Cycling Focus

Whether you’re lifting weights or sprinting on a bike, your abdominal muscles will be contracting to splint your abdominal wall. The Valsalva maneuver (trying to push air out with a closed mouth and nose) makes your torso firm and rigid. This protects your spine and abdominal contents, and it helps deliver optimal force to your endeavor. The next time you engage in a full-power sprint or acceleration, note the firmness of your entire abdomen. The oblique crunch exercise will help train this musculature and help prevent injuries such as a hernia or back strain.

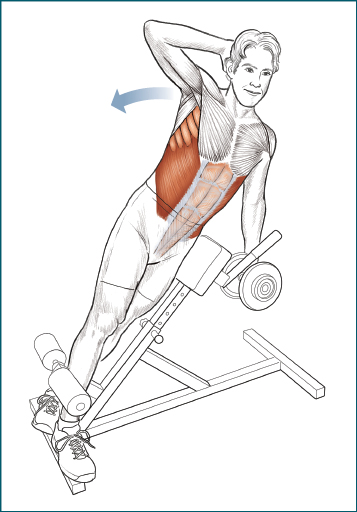

Variation

Incline Oblique Crunch

Position yourself so that the side of one of your hips is resting against the pad on an incline roman chair. Your feet should be side by side and wedged under the foot pad. Hold a dumbbell with your arm hanging straight downward. The other arm should be bent at the elbow with your hand resting on the back of your head. Bend sideways toward your downward hip, and lower the weight toward the floor. Slowly return to the starting position. To isolate the sideways movement, make sure you do not bend forward or backward at the waist.