CHAPTER 1

The Cyclist in Motion

In cycling, as in any other athletic endeavor, the athlete’s body must have a strong, solid base. This is the key to reaching top performance, avoiding injury, and achieving longevity in the sport. For you to obtain your peak performance, all your systems must be operating in concert and as a single coordinated unit. Many cyclists fall into the trap of thinking that cycling is all about the legs. Unfortunately, it is not that simple. Your legs, hips, and buttocks do generate the majority of your cycling power, but to stabilize the lower half of your body, you need to have a strong abdomen, back, and upper body. All sections of your body must work together to stabilize the bike and deliver maximum power to the pedals.

This book explains the anatomy of cycling through various training exercises. With this knowledge base you will have better focus during your workouts. You will be able to design your program based on the understanding that complete balance and strength are the key to successful and injury-free riding. The illustrations and descriptions in each chapter will show you how each exercise applies to cycling. You’ll be able to take what you’ve trained in the gym and directly apply it to your training on the road. Focusing your mind on the cycling aspect of the workout will enable you to make the best use of your time while working out in the gym. As a result, you will get more benefits out of each exercise.

This book emphasizes the need to train your entire body. No single chapter in the book is more important than any other. Cycling is a full-body activity. This will become clear as you read the anatomic description of the cyclist in motion. Each area of the body plays a vital role in distributing your power to the pedals, controlling your bicycle, and preventing injury. If you lack training in a particular area of your body, the entire system falls out of alignment. This will not only cause a degradation in performance, but may also result in pain or injury.

Muscle Form and Function in Cycling

The cyclist in motion is amazing. So many aspects of human physiology come into play when you ride a bicycle. Your cerebral cortex supplies the motivation and plan of attack when you climb onto your bike. You effortlessly maintain the stability and direction of your bicycle through the unconscious balance and coordination provided by your cerebellum. Your heart, lungs, and vascular system supply much-needed oxygen to the mitochondria of your muscles. Through both aerobic and anaerobic energy conversion, your muscles contract and perform a huge amount of work. All this work creates heat, and your skin and respirations help keep the temperature well regulated. Your skeletal system supplies the structural foundation of the entire system. Nearly every physiologic system needs to function in coordination to allow you to complete your bike ride. If you stop and think it through, you realize that it’s truly remarkable!

Although each of these systems can be further broken down and exhaustively explained, Cycling Anatomy focuses on describing how to train the various muscles used while riding a bike. To help you understand why weight training improves performance, let’s begin with a brief explanation of muscle physiology. Once you understand how a muscle works, you’ll also understand the optimal muscle position and, hence, the importance of proper form during your exercises.

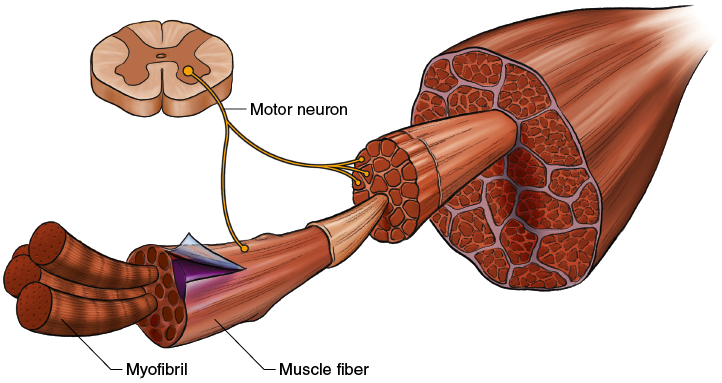

The fundamental functional unit of the skeletal muscle is called the motor unit. It is composed of a single motor nerve (neuron) and all the muscle fibers it innervates. Each muscle fiber breaks down into numerous ropelike myofibrils that are bundled together (see figure 1.1). By activating more or fewer motor units, the muscle generates a gradation of tension. Graded muscle activity refers to this variable tension generation. The frequency at which the nerve activates the motor unit also contributes to muscle tension. The most notable example of this is tetanus, which occurs when the nerve fires so fast that there is no time for relaxation of the muscle. When you decide to lift a particular weight in the gym, your brain controls both the number of motor nerves fired and the rate at which the firing occurs. The brain is stunning in its ability to estimate the needed effort. Only rarely do you realize your brain made a miscalculation. For example, if you pick up a milk carton that you think is full but is actually empty, you will rapidly lift the carton far beyond the spot you intended. In this situation, your mind makes an estimation that is proved wrong, and a poorly coordinated movement results.

Figure 1.1 Details of a muscle fiber. Adapted, by permission, from National Strength and Conditioning Association, 2008, Essentials of strength and conditioning, 3rd ed. (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics), 5.

Composed of actin filaments and myosin filaments, muscle fibers work like a ratchet system. Figure 1.2 shows the functional structure of a muscle. The action of a muscle fiber can be compared to a rock climber on a rope. In this analogy, the rope represents muscle actin, and the climber represents muscle myosin. Just as a climber pulls himself up with his arms, the myosin pulls itself along the actin. Imagine the climber clinging to a rope. To move upward, he locks his legs, outstretches his arms, and pulls. Repeatedly, myosin climbs the actin. As the myosin moves along, the muscle fiber shortens, or contracts. This creates tension and allows the muscle to perform work.

Figure 1.2 Actin and myosin filaments in the muscle fiber work like a ratchet system. Adapted, by permission, from National Strength and Conditioning Association, 2008, Essentials of strength and conditioning, 3rd ed. (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics), 7.

Each muscle has an optimal resting length. This optimal length represents the perfect compromise between having a large number of cross-linked actin and myosin while still leaving enough “spare rope” for the myosin to climb up. Overstretching or understretching wastes the full energy potential of the muscle. This is why a proper fit on your bicycle is so important. If your seat is too low, the muscles won’t be stretched to the optimal length; if your seat is too high, the muscles may be overstretched.

Your position while lifting weights is just as important as your position on the bike. To ensure that you optimally work your muscles while in the gym, you need to follow the form laid out in this book for each exercise. Weightlifters often forgo proper form in order to increase the amount of weight lifted. This is counterproductive. The amount of weight takes second priority to the necessity of doing the exercise correctly. This book shows you the proper technique for effectively working the various muscle groups. Pictures are worth a thousand words, and the many illustrations in the book will guide you by demonstrating ideal form and subsequent muscle fiber position. Following these images will enable you to get the most out of your workout.

Figure 1.3 shows proper cycling position on a road bike. Note that there are five points of contact with the bicycle (legs, buttocks, and arms). In addition, most major muscle groups will be engaged during the cycling motion. Individual chapters of this book will focus on the anatomy of various body sections. But before we focus on particular exercises and individual areas of the body, let’s look at a brief overview of the anatomy of the cyclist in motion.

Figure 1.3 Proper cycling position.

If you need help properly fitting your bicycle, you can find information in Fitness Cycling (Human Kinetics, 2006). You can also have a professional bike fit done. Check your local bicycle shops and clubs for recommendations on the best fitting services.

Because the cranks on a bike extend 180 degrees in opposite directions, one of the cyclist’s legs will be extended when the other leg is flexed. This allows the flexor muscles on one leg to work at the same time that extensors are firing on the opposite side. With each rhythmic turn of the crank, the legs will cycle through all the various muscle groups. This is why cycling is a great exercise and why the pedal stroke is such an efficient means of propulsion. In proper form, you should have only a slight bend at the knee when your leg is in the 6 o’clock position. This stretches the hamstring to the ideal length and prepares for optimal firing during the upward pedal stroke. At the same time, the opposite pedal is at the 12 o’clock position, causing your thigh to be nearly parallel with the ground. This optimizes the gluteus maximus for maximal power output during the downward stroke and the quadriceps for a strong kick as your foot rounds the top of your pedaling motion.

As you rotate through the pedal stroke, your ankle will allow your foot to smoothly transition from the knee-flexed position to the knee-extended position. Just as the flexors and extensors of your upper leg alternate as they travel in the pedaling circle, your calf and lower leg muscles will add to the power curve during most of the pedaling motion. The calf and lower leg muscles will also help stabilize the ankle and foot. As discussed earlier, the maximum energy potential (tension) of the muscle depends on the ideal amount of overlapping actin and myosin. Proper seat height plays a key role in establishing this proper muscle position. If you’ve ever tried to ride a kid’s bike with a low seat, you probably have a good idea of how poorly your muscles perform when they are not positioned correctly.

Because of the basic bent-over position of the rider on a bike, a strong and healthy back is crucial to cycling performance and enjoyment. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t ride if you’ve ever had back problems. Rather, it means that you’ll need to strengthen and care for your back if you want to have a long cycling career. The erector spinae, latissimus dorsi, and trapezius muscles support the spine as you lean forward on the bike. When riding in the handlebar drops, these muscles will help flatten your back, providing better aerodynamics. Riding also stresses your neck. Both the splenius and the trapezius help keep your eyes on the road by extending your neck. Again, because of the strain on all these muscles, proper conditioning of your back is a necessity for healthy and pain-free riding.

The rectus abdominis, transversus abdominis, and abdominal obliques (internal and external) provide anterior and lateral support to the torso, countering the well-developed muscles of the back. If either the back, anterior, or lateral muscles are weak compared to the others, you’ll experience poor spinal alignment, unnecessary spinal stress, and pain. Back pain may have nothing to do with malfunctioning or weak back muscles. It may, in fact, be caused by a lack of conditioning of the abdominal muscles. This is an excellent example of why you need to work on strengthening the entire system rather than a few selected parts of the whole.

Your arms contact the bike for both control and power delivery. While you are holding the handlebars, each arm should maintain a slight bend at the elbow. As you pedal, the flexors and extensors in your arm will alternate from contraction to relaxation. The biceps, triceps, and forearm muscles all work in unison to stabilize your torso via the shoulder joint. Because of your riding position, your shoulder is constantly under pressure. Numerous muscle groups—including the rhomboid, rotator cuff, and deltoid—help maintain proper stability and position.

Your chest muscles support and balance the musculature of your back and shoulders. The pectoralis major and minor allow you to lean forward on the bike and move the handlebars from side to side while climbing. Notice that the form of a rider with his hands in the handlebar drops mimics the position for push-ups or the bench press.

From this brief overview of the anatomy of the cyclist, it is clear that cycling involves the entire body. The various exercises in this book will help you optimize your riding through complete-body training. No area of the body is less important than any other area, so you should be sure not to bypass any chapters. Remember, balance and symmetry are the keys to proper form—and proper form is required for you to gain power and to limit the risk of injury.

The exercises in each chapter will not only improve your strength but will also improve your flexibility. Studies have shown that good flexibility prevents injury and optimizes power output. Your ability to meet the cardiorespiratory demands of cycling will also be improved by work in the gym. During your gym workouts, vascular structures that distribute blood to the muscles will be enhanced, and this will ultimately pay dividends with oxygen delivery to the muscles during high-demand workouts.

Finally, resistance training also has health benefits for your bones. Cycling allows the rider to exercise without unduly stressing the joints. However, this benefit also has a downside. In any type of training, stress develops strength. Because of the smooth pedaling motion, very little stress occurs at the bone. Athletes who only participate in cycling have an increased risk of osteoporosis. This is another reason why weight training is crucial for avid cyclists. Time spent in the gym will help prevent weak and injury-prone bones. Resistance training enhances bone mineralization, making your bony architecture stronger. So when you’re in the gym training, you’re gaining not only fitness but also long-term health benefits.

Strength Training Principles and Recommendations

Before you hit the gym, you need to understand a couple of training principles. The general adaptation syndrome (GAS) provides the fundamental construct for weight training. The GAS is made up of three phases: alarm reaction, adaptation, and exhaustion. The human body likes to maintain homeostasis. It constantly works to resist change and remain at rest. Every time the body experiences a new stress—such as a longer-than-normal bike ride or weightlifting—the body becomes “alarmed.” The stressor disturbs the natural homeostasis and moves the body out of its comfort zone. Phase 2 occurs when the body tries to mitigate the stress by adapting to it. The body will reach a new, higher level of homeostasis as a result of the adaptation. Ideally, as you train, you’ll repeat phases 1 and 2 to continually improve your level of strength and fitness. If you overdo it, however, you may overwhelm your body’s adaptive abilities. This will cause you to reach the third phase of the GAS: exhaustion. You’ll find that your training is a fine balance of stress and recovery. Be sure to allow yourself adequate rest between workouts. Remember, adaptation and conditioning come while you are resting and recovering, not while you are working out.

Periodization is another key training concept that goes hand in hand with the GAS. All training should be based on a well-planned, systematic, and stepwise approach that involves training cycles being built one on top of the other. This hierarchical structure continually builds on previous gains while giving the body time to adapt and condition. A good periodization program will enable you to avoid overtraining and to continually improve your fitness level. Think of the periodization program as the big picture of your training. The program will help you work toward particular periods when you want peak fitness. The various training periods can vary in length, but they will usually range between two and four weeks. Thus, as you use this book to plan your various workouts, you should choose different exercises during each block in an effort to continually “alarm” your system. This is the best way to improve your strength and conditioning.

Scientific studies have shown that strength training improves endurance performance. It is not enough for you to merely go put miles on your bike. If you truly want to reach your potential, you’ll also need to use a weight training program. Resistance training enhances strength, blood flow, and oxygen delivery to the muscles; all these attributes will improve your cycling performance.

It is not within the scope of this book to provide complete workout programs. Rather, the goal is to show the cyclist proper weight training exercises and correct lifting techniques. Each chapter offers a variety of exercises, and during the course of your training, you should vary the exercises that you choose to use from each chapter. To help you get the most out of your time in the gym, you should follow these general rules for training:

• Work your entire body. As mentioned earlier, focusing only on your legs and buttocks can result in instability and possible injury. For you to obtain peak performance, your entire body must be in equilibrium. You should choose a program that includes exercises from each chapter of this book. This will help ensure that your program covers all the muscles involved in cycling. You’ll find that different exercises stress different things, such as flexibility, accessory muscles, primary muscles, or stability. For each area of your body (arms, trunk, back, buttocks, legs), you should pick a few exercises to use during each training period. I also recommend that you cover multiple body parts during each visit to the gym. This is different from pure bodybuilding programs. Those programs often involve working only certain body parts during each visit, and they also require the person to visit the gym five or six times per week. As a cyclist, you need to continue with your cardiorespiratory training; therefore, you should perform resistance training no more than three days a week. The other days should be spent riding your bike!

• Remember that consistency is the key to success. Try to set a program and stick with it. Strength and conditioning are all about building on your previous gains and workouts. Working out two or three times per week will improve your power output and fitness. If you have limited time, try to schedule at least one day per week in the gym in order to maintain previous gains. Deconditioning is one of your worst enemies. If you fail to visit the gym for weeks at a time, you will lose previous training benefits. Unfortunately, loss occurs much more rapidly than the gains, so you will find yourself fighting an uphill battle if you inconsistently visit the gym.

• Vary your workout program. Every two to four weeks, you should set up a new training program in order to keep your body under stress. Adaptation is the key! Your body improves its strength and fitness through adaptation. (A more thorough explanation can be found in Fitness Cycling.) Adaptation is your body’s response to a given stress. Your job is to keep your body surprised by the workout so that you get the most adaptation possible. This book provides many exercises so you’ll have plenty of choices to keep your workout fresh and new.

• Vary the exercises within your program. Obviously, you should not plan on doing every exercise in the book when you go to the gym. (That would take forever and likely cause injury!) During each training block, you should choose a group of exercises from each chapter so that you are working your whole body. You should also try to use a combination of free weights, machines, and the stability ball. By training with a wide variety of exercises, not only will you keep your body stressed, but you’ll also keep your mind interested in going to the gym. When practical, you can also exercise your arms or legs individually and in tandem. This will ensure that your weak side isn’t being supported by your strong side.

• Mimic your cycling position. While doing weight training exercises, try to mirror your position on the bike. For example, when doing calf raises, position your feet the same way your cycling shoes interact with the pedals. This will help focus the gains you achieve so that they can be directly applied when you are on the bike. Don’t go overboard with this, however. Remember that well-rounded strength will help stabilize joints and prevent injury.

• Visualize riding your bicycle. While lifting in the gym, you can enhance your workout by thinking about the ways the exercise relates to riding. For example, when performing a squat, think of sprinting on your bicycle. As you strain to stand upright with the barbell, imagine powering the cranks downward through your pedaling motion. With the final repetition, see yourself nipping your opponent at the line for the win! The information for each exercise includes a Cycling Focus section that shows how the exercise relates to your position on the bike. However, you shouldn’t limit yourself to what is contained in this section. If you can feel or visualize other applicable cycling positions and situations, then your training will only be further enhanced. Don’t underestimate the value of visualization. Most professional athletes incorporate frequent visualization in their training regimen.

Types of Weight Training Workouts

Weight training can be done using various types of workouts. A well-rounded program touches on all the various workout strategies at some point. As previously discussed, for a given training block, you can focus on one specific type of workout. During subsequent training blocks, change the type of training so that you get the most adaptation possible. For example, if you do circuit training during your first block, your second block should be something different, such as low weight–high repetitions. You can use the various types of training in any order that you like. However, keep in mind that it is better to work up to high weight–low repetitions in order to avoid injury from lifting heavier weights. Again, setting up specific workouts for your cycling goals is beyond the scope of this book. Mix and match the following types of workouts when creating your training program.

The key to success is efficient training—that is, getting the most out of your effort. Preplanning your workouts and creating a workable training program will greatly enhance your performance over the course of your training season.

• Low weight–high repetitions. This workout will help you achieve a sustained strength without substantially bulking up your muscle mass. This is good for cyclists because you’ll want to build the most strength with the least amount of mass (that’s what enables you to ride up hills the fastest!). This type of workout will also help develop your cardiorespiratory fitness and your ability to crank out longer periods of hard riding. During each set, you should be able to complete 10 to 15 repetitions.

• High weight–low repetitions. This workout will help you develop raw power and strength. Whether you need to surge on a steep climb or sprint for the finish, pure power will help you reach your goal. For this workout, the weight is the maximum amount you can lift 4 to 8 times. Generally, you should do 2 or 3 sets of each exercise. Although this type of workout does build more bulk, it is appropriate for cyclists at certain times. You will usually need someone to spot you during these exercises.

• Circuit training. This workout involves moving through numerous exercises without much rest in between the various sets. Generally, this type of workout covers the entire body, and your heart rate is elevated throughout the entire workout. Circuit training not only builds strength but also improves cardiorespiratory fitness. This will pay dividends when you spend time at your anaerobic threshold while training or racing.

• Pyramid sets. In this type of training, the weight or repetitions are either increased or decreased for each set during the workout. You should do 3 sets per exercise. For example, in the first set, you may do 10 repetitions. For the second set, you would increase the weight and do 8 repetitions. For the third set, you would increase the weight again and perform 6 repetitions. The workouts usually focus on developing raw power and strength.

• Supersets. These workouts consist of a single set that includes a large number of repetitions. As you begin to tire during the set, the weight is reduced so that you can continue the repetitions. A typical set will have 30 to 40 repetitions. These workouts are very tiring, and they help you develop sustained strength and power. At some point, every cyclist should include this type of workout in her gym training. You’ll be amazed at the driving power you have on your bike after you finish a training cycle of supersets.

Warm-Up, Cool-Down, and Stretching

You must take good care of your body before, during, and after your workouts. When you arrive at the gym, you should do a 5- to 10-minute cardio warm-up. This could be done on a stationary bike or a treadmill. I prefer the rowing machine because it works all the muscles at the same time. Each chapter includes a brief description of a warm-up that focuses on the muscles discussed in that chapter. Note, though, that since you will be working all the muscle groups during each workout, you’ll need to warm up in a way that covers all areas.

After you get the heart rate up and feel that the muscles are warm, you should take 5 minutes to stretch. You should hold each position for at least 30 seconds and remember not to bounce while stretching. During your workout, if you feel a muscle cramping or causing you pain at any time, take a few moments to assess the situation. If the discomfort continues, stop the workout and spend some time stretching the troubled area. Once finished with your workout, you should stretch again. This will enhance the benefits of the weight training you just completed. Studies have shown that a well-stretched muscle provides greater power output and performance when compared to a nonstretched muscle that is similarly conditioned.

Strength, flexibility, and cardiorespiratory fitness all play a role in your cycling success. Complete fitness comes when all three of these are optimized, so you need to balance your entire training program to accomplish this. Visiting the gym should be an integral part of your complete training program, and the gains made will definitely improve your conditioning on the bike.