CHAPTER 5

Back

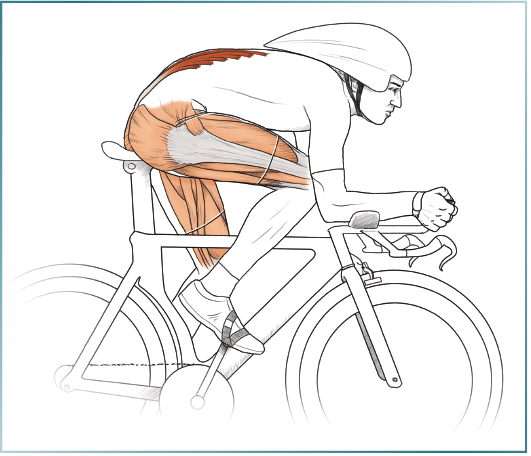

The importance of a strong and fit back cannot be overemphasized. Your back and spine provide the foundation for almost every activity that you perform, and cycling is no exception. Unfortunately, back problems are a frequent complaint of cyclists. Because of the bent-over position on a bike, your back muscles are constantly engaged. This stress can wreak havoc on your body if you’re not conditioned and trained to withstand the ongoing effort. In addition to withstanding the strain of your position, your back must also provide a solid base that enables you to generate power during your pedal stroke. Your back muscles stabilize your spine and pelvis, allowing your legs to generate maximal power.

The best strategy for a healthy back is to proactively condition yourself to avoid any problems before they arise. The exercises in this chapter will help you do just that. You should start slow and use lighter weights during your early workouts. Take your time building strength in your back—this will pay dividends in the long run. When starting out slow, you may often think that the weight is too light. Be patient. The early work lays the foundation for your future training with heavier weights. Even if you think you are lifting a minimum load, you’ll often feel the effects a day or two after the workout. Remember, adaptation occurs during your rest days, so be sure to let your muscles adequately recover. This includes not doing a huge ride the day after you do a back workout in the gym.

This chapter contains exercises that will prepare your back for the stressors of riding and racing. As with many of the exercises in this book, the exercises for your back will involve some crossover, which means multiple muscles will be worked by the same exercise. However, your focus should be on the muscle groups listed under each exercise. This will help you get the most out of your training, and by thinking about specific muscle groups, your form will likely improve both in and out of the gym.

Skeletal Anatomy

The spine is the fundamental pillar of your body. It includes 7 cervical vertebrae (C1-C7), 12 thoracic vertebrae (T1-T12), 5 lumbar vertebrae (L1-L5), a fused sacrum (S1-S5), and a fused coccyx. All support and movement of your torso is made possible by the stacked vertebrae housing the spinal cord. Each vertebra has multiple contact points with the vertebra above and below it (see figure 5.1 on page 78). These contact points are called articular facets. At each level, a lateral canal (intervertebral foramen) is formed that allows nerves to extend from the spinal cord to various destinations throughout the body. A large number of ligaments help stabilize and hold the vertebral bodies together.

Figure 5.1 The spine.

Intervertebral discs cushion the intersection between two vertebrae and allow smooth movement of the spine. The fibrous outer section of the disc is called the annulus fibrosus. The inner section, which helps distribute pressure and stress, is called the nucleus pulposus. A herniated disc occurs when there is a breakdown of the fibrous outer band and a bulging out of the nucleus pulposus. This bulge can happen anywhere around the disc, but when it happens near the vertebral foramen, it can compress the exiting nerve and cause excruciating pain and weakness.

Cyclists have a tendency to develop back problems because the riding position places anatomical stressors on the curved spine. Normally, the lower back has a lordotic curve that causes the lumbar spine to appear to bend inward. When you ride your bike, this curve is flattened. Cyclists like to ride with a “flat back” because it improves aerodynamics. However, the flattening of your lordotic curve can place increased pressure on the anterior aspect of your lumbar vertebrae and intervertebral discs. If the force becomes too great, disc herniation can result. By easing into your training and working the muscles of your back and abdomen in the gym, you can alleviate many of the problems that may arise from your cycling position.

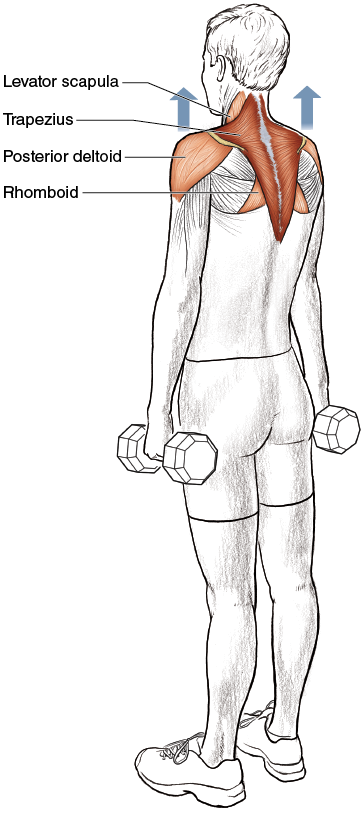

Back Musculature

If you ride frequently, your back will become one of the most well-developed areas of your body. Multiple layers of muscles provide support for and movement of both the spine and the shoulders (see figure 5.2). The large, triangular trapezius is the outermost muscle. This muscle originates at the base of the skull and along the spine and travels across the back to insert in the scapula and clavicle. The trapezius performs multiple actions because of its large, fanned-out anatomy with fibers running in multiple directions. From a functional standpoint, the muscle can be divided into three sections:

Superior fibers: Scapular elevation and abduction (shrugging or lifting the shoulders)

Middle fibers: Scapular retraction (pulling the shoulder blades together at the midline)

Lower fibers: Scapular depression (pulling the shoulder blades downward)

Combination of fibers: Scapular rotation

The latissimus dorsi is another large, triangular muscle of the back. It originates along the lower spine and upper posterior ridge of the pelvis (iliac crest). At the opposite end of the muscle, the fibers come together to form a tough fibrous band (tendon) that inserts onto the upper portion of the humerus (near the insertion of the pectoralis major). Contraction of the latissimus dorsi pulls the humerus downward and backward, resulting in shoulder extension. This muscle also performs shoulder adduction (pulling the arm inward toward the body).

Lying under the trapezius, the levator scapula, rhomboid major, and rhomboid minor connect the scapula to the upper spine. As the name implies, the levator scapula elevates the scapula. The rhomboid major and minor work in conjunction with the middle fibers of the trapezius to retract the scapula. All these muscles help stabilize the shoulder and the upper back.

The erector spinae muscles run along the length of the spinal column. Their primary role is stabilization and extension of the spine. When you hold your bent-over riding position on the bike, the erector spinae muscles contract and bear the brunt of the load. Many of the back exercises will either directly or indirectly train these vitally important muscles.

Warm-Up and Stretching

As mentioned in the previous chapters, a good warm-up is essential to preventing back injury. Riding a stationary bike is an effective way to warm up for the exercises in this chapter. Rowing is also a great cardio warm-up; it fires up your entire system while specifically warming the muscles of your back. Make sure you perform adequate stretching before getting into the exercises that follow. You can mimic some of the back exercises without using weights; you should hold each position for at least 30 seconds. You should also do some easy back bends and extension movements.

Figure 5.2 Muscles of the back.

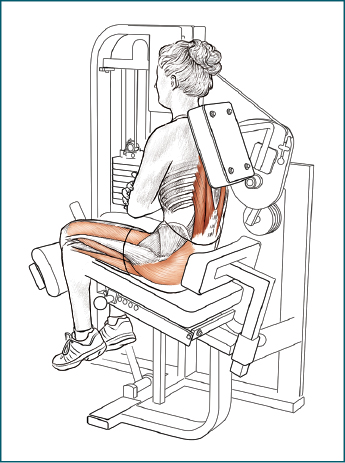

Seated Row

Execution

1. Place your feet shoulder-width apart on the rowing platform. Facing a low pulley, grip the handles using a thumbs-up grip. Your arms should be extended.

2. Keeping your back straight, concentrate on pulling your shoulder blades together, toward your spine. (Your arms should still be straight.)

3. Once your shoulder blades are retracted fully, pull the handle toward your chest, keeping your elbows tight to your sides.

4. Return to the starting position, first extending your arms and then letting your shoulder blades relax.

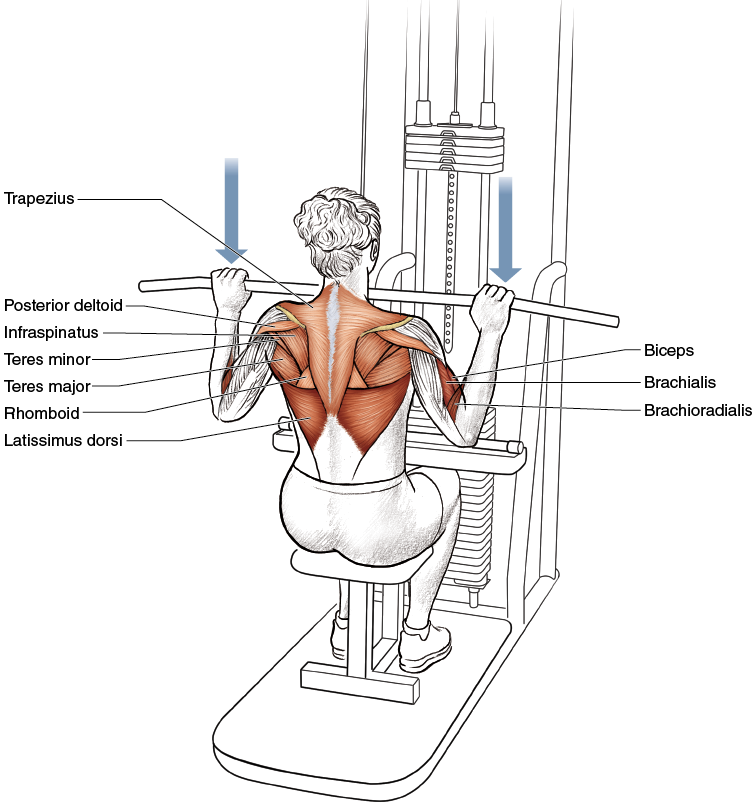

Muscles Involved

Primary: Trapezius, latissimus dorsi, posterior deltoid, biceps

Secondary: Rhomboid, teres major, teres minor, erector spinae, brachialis, brachioradialis

Cycling Focus

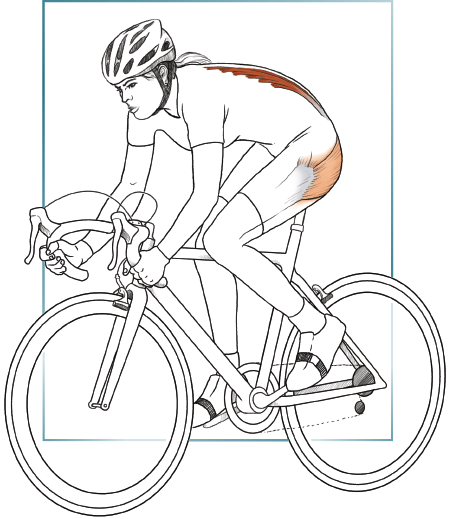

If you ride on varied terrain, at some point you’ll inevitably encounter a steep section of road. Even in your bike’s easiest gear, you can find yourself struggling to keep your forward momentum. Each turn of the pedals is a chore, and you’ll have to rely on your arms and back to pull on the bars as you power through each rotation. The seated row exercise will help you develop adequate force in your arms and back. The grip position shown in the main illustration mimics holding your handlebars on the drops or hoods. Feel free to use a straight-bar attachment (grip with palms down) to mimic having your hands on the handlebar tops.

Variation

Machine Row

The machine row provides you with the same workout. However, you will lose some of the lower back workout because your chest is supported against the pad.

Shrug

Execution

1. Keeping your back straight and your arms extended, hold a dumbbell in each hand.

2. Without bending your arms, shrug your shoulders straight up toward your ears.

3. Slowly return to the starting position.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Trapezius

Secondary: Deltoid, levator scapula, erector spinae, forearms (grip strength)

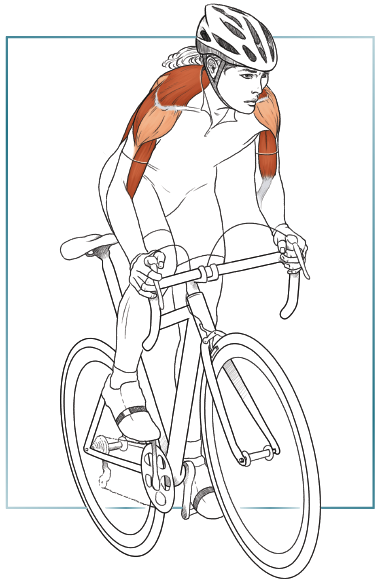

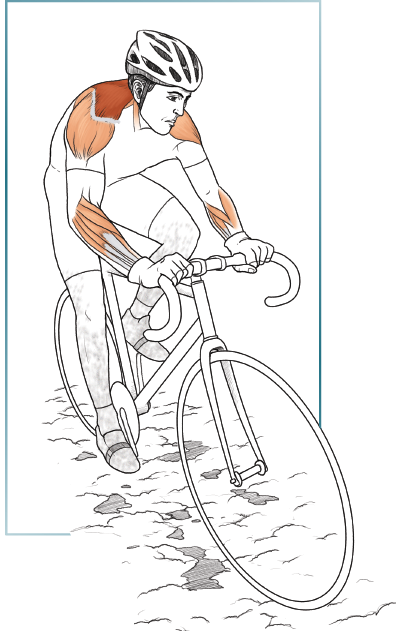

Cycling Focus

Most of the muscles worked in this exercise are also used when you’re leaning forward on your bike with your hands on the handlebars. These muscles will be under even greater stress when you start to climb out of the saddle. When standing, you’ll lean forward, and more of your upper body weight will have to be supported by your shoulders and arms. You will also rely heavily on these muscles for support when you encounter rough roads. Although many cyclists never ride the old, cobbled roads of Europe, most will encounter plenty of construction zones and dilapidated country roads. With each jolt transferred from the road to your handlebars, your arms and shoulders will flex and contract to act as shock absorbers.

Variation

Barbell shrug: You can use a barbell instead of dumbbells for this exercise. Standing on stability disks while performing the exercise is a good way to increase the work for your legs, lower back, and torso.

Pull-Up

Execution

1. With your hands positioned slightly wider than shoulder-width apart, hang from the pull-up bar.

2. Without swinging, pull your chin up to the bar.

3. Slowly return to the starting position (arms extended).

Muscles Involved

Primary: Latissimus dorsi, biceps, brachialis, brachioradialis

Secondary: Posterior deltoid, rhomboid, teres major, teres minor, infraspinatus, external oblique, internal oblique, trapezius

Cycling Focus

This is a classic exercise that works most of the muscles in your back. It also places emphasis on the biceps, brachialis, and brachioradialis. As a cyclist, you’ll rely on all these muscles to support your body and deliver the optimal drive to the cranks. Whether you’re climbing, sprinting, or just cruising with your hands on the bars, some of the muscles trained in this exercise will be used. I like any exercise that works multiple muscle groups at the same time, and the straightforward pull-up definitely fits the bill. This exercise can be an effective part of almost any workout program.

Variation

Pull-up assist machine: This machine is a fantastic aid if you have difficulty performing an unassisted pull-up. The weight reading on the machine is the amount of aid provided during a pull-up. Hence, as you increase the amount of weight on the machine, the pull-up becomes easier.

Pull-Down

Execution

1. Sit with your thighs tucked under the pad. Use a wide, palm-out grip to grab the pull-down bar.

2. Keeping your body motionless, pull the bar downward until it touches your chest.

3. Return to the starting position (arms extended).

Muscles Involved

Primary: Latissimus dorsi, biceps, brachialis, brachioradialis

Secondary: Posterior deltoid, rhomboid, teres major, teres minor, infraspinatus, external oblique, internal oblique, trapezius

Cycling Focus

Like the pull-up, the pull-down is an exercise that gives you a lot of bang for your buck. The muscles of your back, arms, shoulders, and torso all contribute to the effort of this exercise. Having a strong back with good stability will keep you injury free and comfortable during training periods that involve heavy cycling. The off-season is a perfect time to bolster these muscles and prepare your body for the stress of the many miles to come. If your back is well prepared for the strain before your training season begins, you can focus on your fitness rather than back discomfort during the season.

Variation

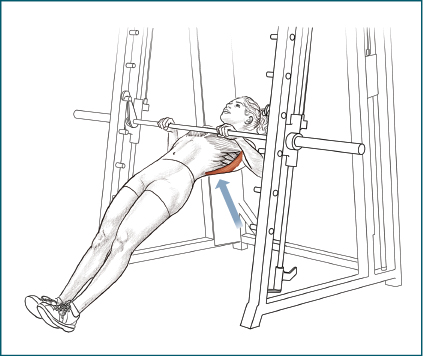

Barbell Pull-Up

This exercise works many of the same muscles as the pull-down and pull-up. Because of the angle of movement, more emphasis will be placed on the posterior deltoid. Position the straight bar on a Smith machine at waist height. Hang under the bar with your arms extended and your torso straight. Your body should make a 45-degree angle with the floor. Looking toward the ceiling, pull your chest up to the bar. Slowly lower yourself and repeat.

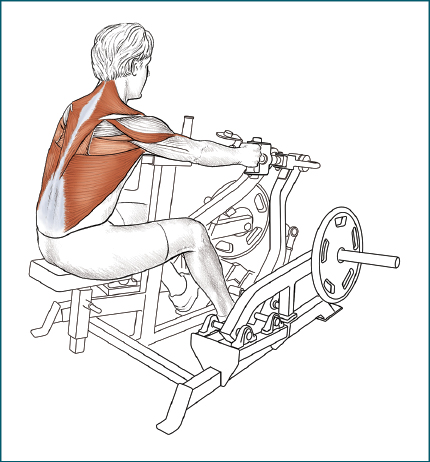

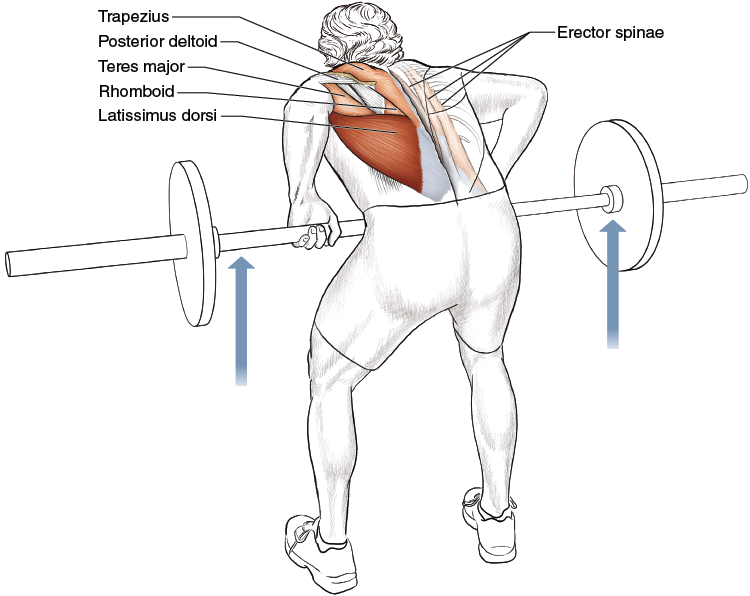

Bent-Over Barbell Row

Safety Tip

You must be sure to bend only at the waist. Your spine should be straight. If you start to arch your back, you’ll put unnecessary strain on your lower back. This may result in injury.

Execution

1. Hold the barbell using an overhand grip with your hands shoulder-width apart and your arms extended. Stand with your back leaning forward about 45 degrees to the floor.

2. Keeping your torso motionless, pull the barbell up vertically to your lower chest.

3. After a brief pause, lower the barbell to the starting position.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Latissimus dorsi

Secondary: Erector spinae, biceps, brachialis, brachioradialis, posterior deltoid, trapezius, rhomboid, teres major

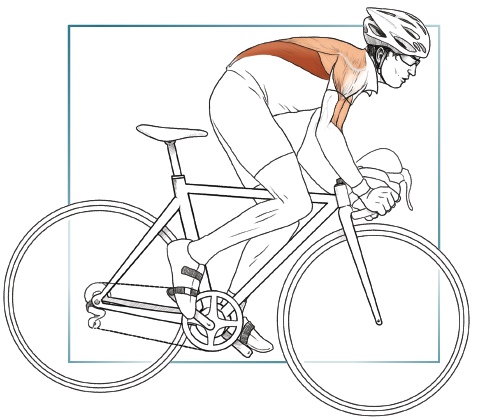

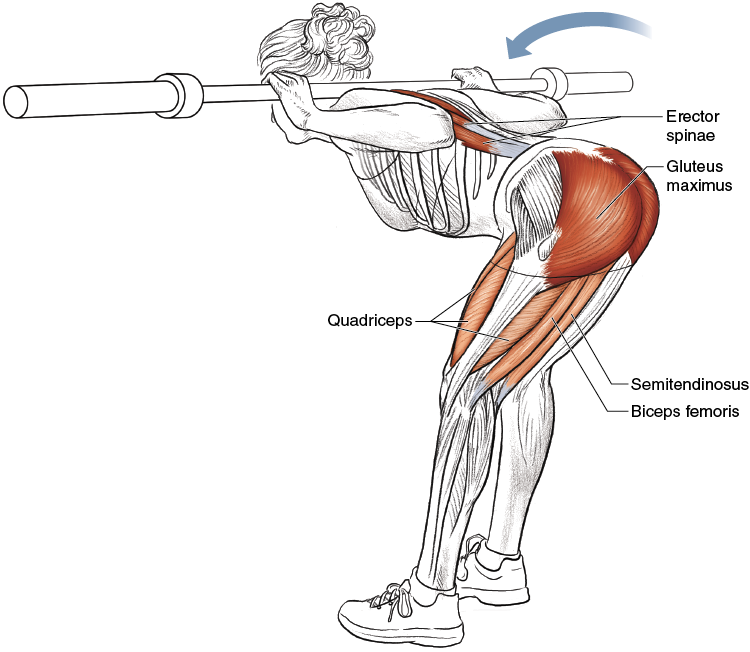

Cycling Focus

From these illustrations, you can see that the position for this exercise closely resembles a common riding position. When riding up a climb with your hands on the hoods, you’ll be pulling rhythmically on the bars. Your latissimus dorsi, shoulders, and arms will help provide stability and the extra drive you need to attack the climb. The bent-over barbell row is also ideal for the cyclist because it works the erector spinae. The angle used in this exercise is very close to your back’s angle when you are on your bike and climbing out of the saddle. By including this exercise in your training program, you’ll be conditioned to withstand the grueling mountains ahead.

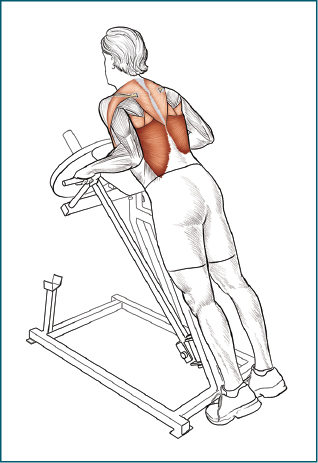

Variation

T-Bar Row

The T-bar row will give you added stability during the exercise. The lower back (erector spinae) will not be worked in this version of the exercise, but this can be beneficial if you’re trying to overcome lower back soreness or injury.

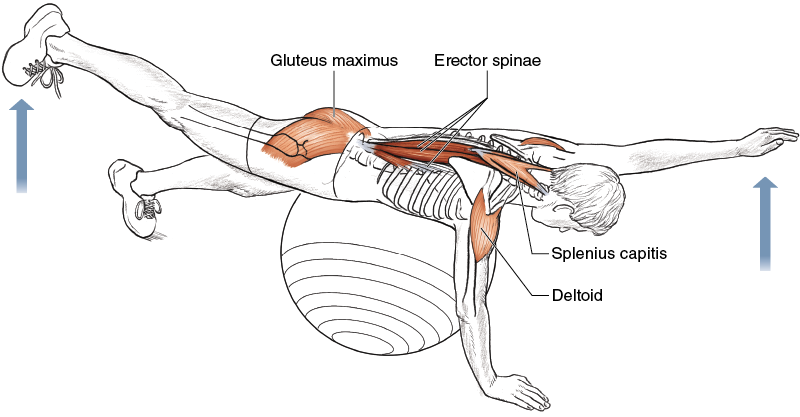

Stability Ball Extension

Execution

1. Lie with your lower abdomen draped over a stability ball.

2. Keeping one foot on the floor, arch your back while raising and extending your arm and opposite leg. Your elbow and knee should be straight (extended).

3. Slowly lower your arm and leg. Curl your body around the stability ball.

4. Repeat the exercise using your other arm and leg.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Erector spinae

Secondary: Splenius capitis, gluteus maximus, deltoid

Cycling Focus

Your erector spinae muscles must withstand enduring workloads when you ride your bike. For the majority of your ride, these muscles will maintain your forward leaning posture. If your back becomes sore or fatigued, the erector spinae muscles are usually the culprit. The stability ball extension is particularly effective because it gives you full range of motion at maximal extension. This will counter the hours you’ll spend with your back arched forward on the bike. Don’t think that you need to use added weights to make this workout effective. Remember that stretching and moving your muscles through their complete range of motion will help you get the most out of your muscle fibers.

Variation

Same-side stability ball extension: A good variation is to raise the arm and leg on the same side rather than on opposite sides as described for the main exercise. This will stress different stabilizers and give you a well-rounded workout.

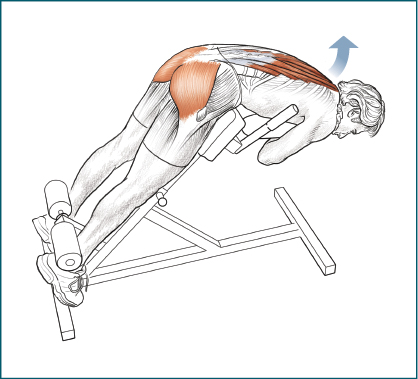

Reverse Leg Extension

Execution

1. Lie with your lower abdomen on a stability ball. Extend both arms forward, and place your palms on the floor. Your legs should be straight, and your toes should be resting on the floor.

2. Keeping your knees straight, slowly extend at the hip, elevating your legs off the ground.

3. Return to the starting position.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Erector spinae, gluteus maximus

Secondary: Hamstrings

Cycling Focus

As previously mentioned, cycling is tough on your lower back. In the gym, you should focus on developing these back muscles in order to avoid future aggravation. The stability ball is an excellent tool because it allows freedom of motion with the added benefit of working all the stabilizer muscles. Remember, a balanced musculature is the key to proper alignment and injury prevention. Because you are so confined in position during your time on the bike, you should perform more range-of-motion exercises in the gym. You’ll ride faster and better if your body is balanced and your muscles have strength through their entire spectrum of movement.

Variation

Incline Lumbar Extension

After you’ve been working this exercise for a while, you can hold weights to increase the difficulty. This exercise can also be done using an incline lumbar extension machine or bench. With the added stability, the workout for the stabilizer muscles is reduced.

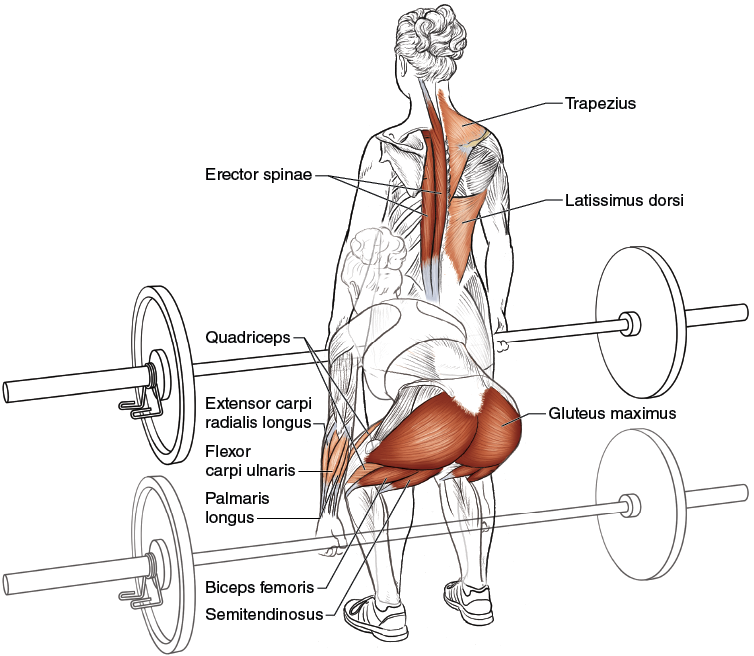

Deadlift

Safety Tip

Correct form is a necessity during this exercise. Keep your head looking upward and your back straight. This will help straighten your spine and help you avoid injury.

Execution

1. Start with the barbell on the floor. Place your feet shoulder-width apart, and grab the barbell using an overhand, shoulder-width grip. Your arms will remain extended for the entire exercise.

2. Keeping your spine straight and your chin up, lift the barbell up to your waist, bending at the hips.

3. Slowly lower the weight back to the floor.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Erector spinae, gluteus maximus, hamstrings

Secondary: Trapezius, latissimus dorsi, quadriceps, forearms

Cycling Focus

As previously mentioned, the erector spinae muscles play a key role in the support of your body while you are on the bike. The deadlift exercise is great for cyclists because not only does it work these fundamental back muscles, but it also works some of the powerhouse muscles that help a cyclist power the cranks. The lower back clearly takes the load in this exercise, but you’ll also get the benefit of strength training for the hamstrings, gluteals, and quadriceps. Again, I like exercises that work multiple muscles concurrently, and the deadlift definitely fits into this category.

Variation

Sumo Deadlift (Wide-Stance Deadlift)

Widen your stance and point your toes outward. Follow the same technique as described for the regular deadlift. You may want to use an over–under grip, as shown. By widening your stance, you’ll emphasize training of the quadriceps and hip adductors.

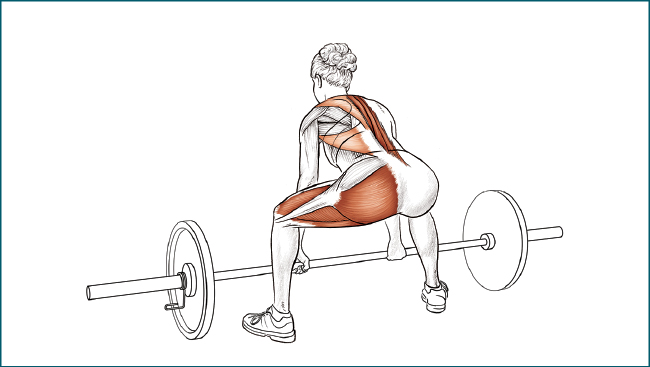

Good Morning

Execution

1. With your feet shoulder-width apart, stand erect with a barbell across your shoulders.

2. Keeping your back straight and your eyes up, bend at the hips until your upper body is nearly parallel with the floor.

3. Slowly return your torso to the upright position.

Muscles Involved

Primary: Erector spinae, gluteus maximus

Secondary: Hamstrings, quadriceps

Cycling Focus

When performing this exercise, you must be careful not to overdo it and strain the muscles you are trying to train. The good morning will help develop the muscles that hold your posture while you’re riding. Having strong erector spinae muscles will also improve your power delivery as well as your form. Ideally, your back should be fairly straight and flat when you are on your bike, with your hands resting on the handlebar drops. Check your form on a trainer or when riding by a reflective window to make sure your back is flat and aerodynamic. Additionally, all the muscles running along your spine, including the erector spinae, will stabilize your spine and reduce the risk of vertebral subluxation (one vertebral body sliding forward onto another).

Variation

Machine Back Extension

When using the back extension machine, you’ll have increased stability. If you’ve had back problems or if you are returning from a back injury, the machine is a good device for easing into a workout of the erector spinae muscles.