Chapter 7. Make Data Relatable

As teams in DevDiv began employing our customer-driven methods, we found there were times when they would become frustrated by the lack of action in response to their discoveries.

For example, I’d work with a team and they would do a fantastic job of identifying their assumptions, formulating them into hypotheses and running round after round of customer interviews. They were doing all the right things, yet it would be difficult to move the project beyond just data collection. These teams would become frustrated, wondering why their validated or invalidated hypotheses weren’t enough to move their teams into action.

If you’re an organization that is suffering from low customer satisfaction scores, a decline in product engagement, or customer indifference toward new products and services, these situations can be very urgent. In the face of those issues, it can be incredibly frustrating when you’re met with inaction or apathy.

In this chapter, we explore the power of generating data that is relatable. This is an incredible hack that, when applied correctly, can inspire people to change their behavior in positive ways.

We cannot influence change with data and numbers alone. You need stories to bring that data to life in a way that captures people’s attention and compels them to action. In a customer-driven culture, your customers’ stories are what keep your employees connected to the company’s mission. Your customers must become more than a set of numbers in a spreadsheet or a collection of responses in a survey.

The same is true of your employees. Their stories of success inspire us to engage in the new culture. They give us examples of how to belong and what it looks like when we behave under the new values that are being promoted.

Therefore, as change agents, we must become masterful storytellers. We must be able to identify key stories from both the customer side and the employee side. We shape these stories, build upon them, and find interesting ways to share them throughout the organization. By applying this hack, we create a roadmap of examples that eventually leads us to our new culture.

Agents of Change: Rescuing the Wild Boars Football Team

On July 2, 2018, John Volanthen, a British cave diver, had literally reached the end of his line. Submerged in flood waters deep within the recesses of the Chiang Rai cave network in Thailand, his team was using a lead line to help him navigate the 2.5 miles of treacherous terrain. The tether was a literal lifeline, helping him find his way back to the entrance of the cave. As he stared at the end of the rope, he realized this was as far as he could go if he wanted to safely find his way back.

John, his team, and Thailand officials were desperately searching for the Wild Boars youth football team.

Twelve boys, between the ages of 11 and 16, had entered the cave with their coach nearly two weeks prior. What was supposed to be an exciting team adventure, exploring the cave’s natural wonders, had turned into a nightmare when a monsoon developed out of nowhere. The rescue team believed that, as the water levels rose, the boys and their coach were forced deeper into the cave to avoid drowning. They feared that without light, food, water, and, most important, breathable air, their chances of survival were grim.

For John, it was becoming increasingly clear that if the rescue team waited any longer, this would cease to be a rescue mission and they would all be forced to accept an unimaginable reality: these children would be lost forever. In that moment of desperation, John did the unthinkable. He took the end of his line reel, stuck it into the mud, and moved forward into the dark cave. If he was going to find these boys, he was going to have to risk traveling without his lifeline.

Thankfully, he didn’t have to travel much farther. After moving into the cave another 15 feet (4.6 meters), his light flashed across what looked like a face. He jerked his head back and his headlamp caught the sight of a boy, squinting against the first light he’d seen in days. John immediately began scanning the area. He found another boy, and then another.

His pulse quickened, “How many of you?” he cried out to one of the boys.

“Thirteen,” the boy replied, shielding his eyes from the light.

“Brilliant.”

He found all of them alive.

Another boy shouted, “Eat, eat, eat.”1 They were starving.

What followed was a harrowing attempt to rescue the boys and their coach. Essentially, the rescue team was left with two options. They could give the boys supplies and have them wait until the water levels dropped, allowing them to walk out of the cave. Surprisingly, this option would require the boys to live in the cave for an unimaginable four months. The rescue team was pumping 1.6 million liters of water out of the cave per hour, but with the monsoon season approaching, it wouldn’t be enough to completely clear out the cave. The chances for illness, injury, or sheer psychological damage were too great. The second option was nearly just as improbable. The team could try to get the boys out.

The plan was audacious, to say the least. They would ask 13 inexperienced divers, who had spent over a week in a dark cave without food or water, to swim a route that had claimed the life of an experienced Navy SEAL. To do this, divers would need to teach the kids how to navigate an extremely difficult scuba dive. Some parts of the cave were so narrow they would be required to take their equipment off to fit through and then reconnect to it on the other side, all while holding their breath, and, one by one, the divers would guide them through the 2.5 miles (4 km) back to their families.

If you turned on any major news network, they were running nonstop coverage of the effort. Experienced divers, ex-military officials, and countless other pundits took to the airwaves to assess and comment on the situation. It seemed like everyone had a theory of whether the boys and their coach would survive. Psychologists were asked about the boys’ potential mental state, and Thai officials were interviewed about every detail. At one point, the divers had snaked a camera into the cave so the boys could communicate with their parents. It was an unbelievable moment of celebration and heartbreak. The boys were so close to their parents, yet so far.

The world was captivated. For weeks, there wasn’t a channel, newscast, news blog, or newspaper that wasn’t covering the story. It had something in it for everyone: a daring escape, an engineering challenge that had engaged the greatest minds, and pride and nationalism as many countries offered their support and resources. For a brief, historic moment, the world was working together, with a common purpose of returning this football team home to their families.

But why?

There are children, just like the boys of the Wild Boars football team, who face dire circumstances every single day. According to CARE, a nonprofit humanitarian effort, measles, malaria, and diarrhea are the three biggest killers of children—all preventable diseases. One in five children lack safe drinking water, and every day almost two thousand children die from diseases related to lack of basic sanitation. More than three hundred million children are starving and are suffering the consequences of long-term malnourishment.

For many, these are alarming and urgent statistics that warrant immediate intervention. Largely, the world remains unmoved. But when 12 young boys’ lives were in peril, the world galvanized itself into action.

Now, to be clear, it was phenomenal to see the best minds come together for those boys in Thailand. In fact, divers were able to successfully rescue every single boy and their coach. It was an incredibly historic moment of triumph for their families and the world.

Yet, it remains incredibly difficult to capture the world’s devotion to all these other issues that children face every day.

Certainly, the story was sensational, which is why it received so much attention. For children, living in poverty has been a systemic problem for centuries, and we’ve all been introduced to the problem in one way or another. However, there was something special about this story of the Wild Boars football team beyond the novelty of it. The story had the power to engage the entire world with concern and common purpose. The reason this story had so much power over the public’s consciousness wasn’t just because it was harrowing and remarkable; it was that it was incredibly relatable.

It didn’t take much for a parent watching CNN in Iowa to put themselves in the shoes of one of the distraught parents in Thailand. Looking at the grainy images of those boys, soaking wet and scared, stuck in a dark, narrow pocket of the cave, it was impossible not to imagine our own children in a similar plight. The boys and their coach in Thailand weren’t a nameless, faceless statistic. They were relatable; they were ordinary people caught in an extraordinary circumstance. Through news coverage, images, and interviews, we learned their stories and shared in their families’ heartache.

Such stories have a profound effect, shifting us to a common goal (in this case, saving the boys and their coach) and inspiring us into action.

The Power of Story on the Brain

In 2010, a group of researchers at Princeton University wanted to explore how communication between a speaker and listener affected the brain. They sat participants down in pairs and instructed the speaker to tell the listener a personal, unrehearsed story. Using sensitive imaging equipment, they scanned each participant’s brains during the communication.

For example, one participant (the speaker) shared a story with another participant (the listener) about attending her high school prom. As the speaker told the story, researchers could see how the story affected the brains of both the speaker and listener.

What they discovered was that both the speaker’s and the listener’s brains engaged in what they called “neural coupling.”2 As the listener heard the story for the first time, his brain activated the same areas as the speaker who was telling the story. This was a remarkable discovery that suggests that stories act as “mental stimulation.” In other words, when we hear a story, the same regions of the brain that would be stimulated if we had experienced the circumstances of the story ourselves are activated.3 In a sense, the act of neural coupling is an act of empathy. It’s our brain’s way of placing us in the circumstances of the storyteller and allowing us to feel and experience the same moments.

This is why storytelling has stood the test of time and why oral traditions still exist. If you’ve ever experienced a profound life event, like a near-death experience, you can probably remember the countless times you were asked to recount the story for your friends and family. Everyone wants to hear what happened, and while you take them through the details, they’re asking themselves, “I wonder what I would’ve done in that situation?” Essentially, our brains are allowing us to learn from one another’s experience. When we hear the story of a friend whose car was totaled in a collision at a nearby intersection, our brains make a note to move through that intersection more carefully in the future. Conversely, if our friend has lost weight while trying a new diet and exercise routine, we want to hear the story so that we can achieve similar results. Stories are the vehicle by which we share our profound successes and our humbling mistakes.

Modern science and centuries of historical evidence indicate that if you want to inspire others to learn and grow, you must become a great storyteller. Stories are the vehicle by which you will drive change and inspire others to adopt the three vital behaviors: awareness, curiosity, and courage.

Companies with great cultures understand this. They invest in professional resources to craft stories, videos, internal intranet blogs, posters, and other media. They know that to inspire or even maintain a movement, their organizations need to be inspired by compelling stories of excellence.

Inspiring Others to Action

As we began to hit our stride in DevDiv, we saw that customer interviews, surveys, concept-value tests, and usability testing were on the rise. It was fantastic to see the energy our product teams were bringing to these interactions and the insights they were gaining from connecting with our customers.

Our team experimented with running “Customer-Driven Alumni” events to try to build community among employees who had gone through our workshops. Although that’s been something that’s been difficult to grow organically, I still delight in the first two groups we were able to gather. In fact, a conversation I had with the second group still stands out to me.

When I asked the group, “So, what’s the biggest problem you’ve been having with this customer-driven way of building software? Anyone have anything they’ve been frustrated with?”

I expected to hear the common frustrations I had already heard from our various product teams. What I expected to hear was about how challenging it was to find customers. I expected to hear how difficult it was to find time in the day to talk to customers. These were the common complaints from the early days.

However, one program manager mentioned a frustration that we hadn’t heard before.

She said, “You know, it’s actually going pretty well. I’ve gotten some really good data and I’ve really enjoyed talking to our customers and learning how they use our products.”

Then, addressing the group, she asked, “I’m wondering how any of you handle handoffs. I have some really good notes and data on these customer calls I’ve been having. I’m going to be moving onto another project, and I just feel like everything I experienced is going to be lost when I hand it over to someone else.”

In more private settings, we heard that product team members enjoyed the connections they were making with their customers but were frustrated by how much data it took to move a decision forward.

To me, the connection between those two frustrations is woven into a single thread. It’s not easy to tell a story with just data alone.

The program manager who worried about handing over her project was struggling because she had real empathy for the customers she had met. She was afraid that the stories of those customers couldn’t be captured in spreadsheets and raw interview notes. If she handed the project to someone else, the momentum of the project she had worked on so hard would be lost.

In the more private conversations, those team members were frustrated by inaction. The feeling was that they’d “done all the right things” and had been “data driven,” but their data wasn’t enough to drive action within the rest of the division. In effect, were being “data rich and action poor.”

Essentially, both of those situations occur because, fundamentally, the story gets lost. The nuance. The essence of the customer. It’s difficult to scale customer empathy because empathy is experienced. It’s difficult to transfer empathy through emails or project status updates. A customer complaint given in a bug/fix report can be hard to empathize with and even harder to be motivated by. “Data can persuade people, but it doesn’t inspire them to act,” says bestselling author and executive coach Harrison Monarth.4

So, how do you scale that kind of customer empathy from team to team? Well, consider the way we humans have been exchanging data for centuries. We’ve told one another stories. Stories give us the meaningful information in a way that sticks. Stories are easy to share and, if done the right way, can drive emotion in us. A great story can make us laugh, cry, or change the way we see the world.

Consider the story you’re reading now. How convincing would it have been if I had given it to you in an Excel spreadsheet? If this story was given to you as a set of raw notes, would you have been able to easily ascertain the fundamental learnings of our transformation? Probably not.

Yet, recalling a meaningful story is effortless for us. That’s why hearing stories of our customers can be so meaningful; these stories can drive us into action.

The Impact Ladder

Let’s consider the following analogy. Imagine that I went on an African safari. During my visit, I had a transformative experience, seeing a herd of elephants move across the savanna. Directly witnessing the majesty of these elephants, the way they care for one another and raise their young, I now realize how important it is to protect these animals.

Our safari guide tells us that these elephants are listed on the endangered species list and that, in Africa, their populations have seen the worst decline in the past 25 years. I’m distraught to learn that this herd was attacked by poachers only months earlier. Hunters had killed nearly half of them, stealing their ivory for the black market.

Seeing their beauty and fragility firsthand, I understand the urgency and the importance of conservation.

Then, I travel back home to Seattle.

I feel compelled to share the transformative experience I had with family, friends, and colleagues. I want them to truly appreciate how important it is that we take care of these animals. Perhaps I start a campaign and try to raise money to donate to the African Wildlife Foundation. I’m inspired and I want to do my part.

In Seattle, far away from the savanna, many of my peers fail to grasp the sense of urgency that I have. They have never been to Africa. Sure, they’ve seen an elephant at the zoo, and some of them might have even heard they were endangered, but there are so many other urgent, closer-to-home issues that they are concerned with. I retweet the latest news and reports on Twitter and share heartbreaking articles about hunted elephants on Facebook. Out of all my friends and colleagues, I get one response back: a sad-face emoji.

Slowly my frustration mounts. “Why can’t people see how important this is?!”

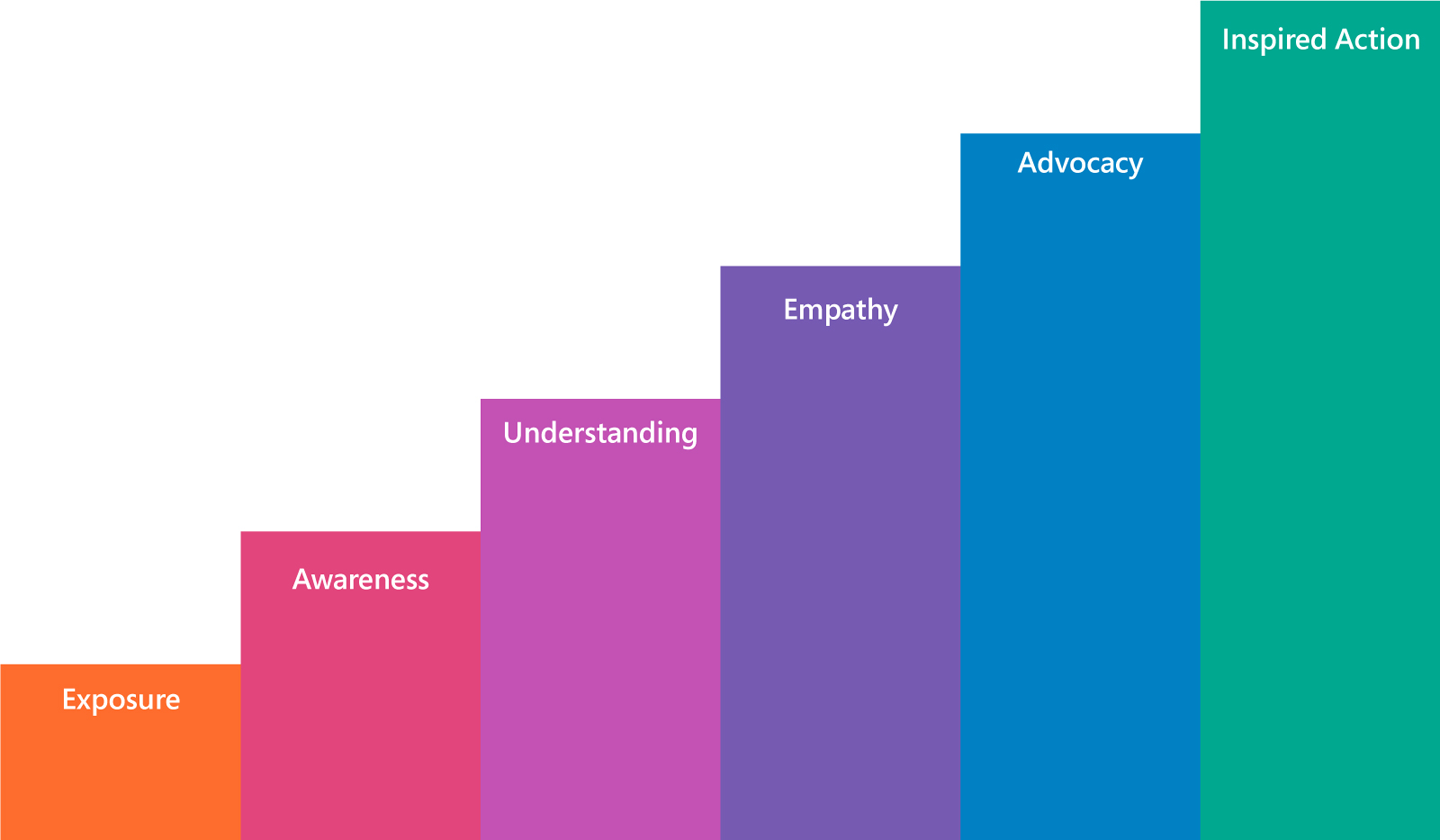

When we consider the level of impact I have in this situation, we can look at my level of influence along an Impact Ladder (see Figure 7-1). Essentially, we can move through the stages of empathy others will have with my story of the elephants.

Figure 7-1. The Impact Ladder

The first stage is exposure: being exposed to the fact that there are endangered elephants in Africa. Then, my friends become aware of the problem of poaching and illegal hunting. I try to move them to understanding why the problem occurs and then build empathy for the pain, suffering, and loss being endured by these animals and why the problem is so important.

But that’s not enough. Empathy isn’t enough when trying to convince others to do something as a result of newfound information. You need to move people from empathy to advocacy. They join you on your mission to get the word out and bring awareness to the issue, and finally, the ultimate goal is to move them to inspired action. Inspired action is when you’ve convinced a group of people that the situation with the elephants is so dire, they must act now.

So, how do you move people from just being exposed to the issue of endangered elephants, to being completely inspired into action?

The very best way would be to take my family, friends, and colleagues on another safari with me. As they sit in the same spot where I sat, looking down on a sunset-drenched savanna and listening to the safari guide explain the nuances of the herd of elephants in the field, there’s a good chance they’d say, “OK. I get it now. I need to do my part to protect these elephants.” There’s really no better way to convince someone of a problem or opportunity than to create a way for them to experience it for themselves.

We know that creating a coexperienced model of learning is incredibly effective, but it’s not always feasible to take every potential donor to the savanna to convince them that saving the elephants is worthwhile. Although we should always strive for creating firsthand experience, it isn’t always achievable. For a customer-driven culture, we should emphasize, as much as possible, firsthand experiences with customers. For situations in which that’s not possible, we need to get creative. As discussed in Chapter 4, this is what Scott Guthrie did when he had his senior leadership team try to use Azure. He manufactured a firsthand experience for his team to truly feel how difficult it was to get started using the service.

If we refer to the Impact Ladder, we can consider the various levels of empathy I might generate from the strategies I employ. Let’s look at each stage of the ladder and how it relates to my ability to relay the elephants’ situation:

- Exposure

- When my coworkers ask about my trip, I mention how awful it is that elephants are still being hunted illegally.

- Awareness

- During a team meeting, I tell my coworkers about the experience I had and remind them how important it is to care for wildlife.

- Understanding

- I send around an article I found online that talks about the issues of illegal hunting in Africa and its effects on the elephant population. It includes the most recent population numbers, showing an alarming decline.

- Empathy

- I create a PowerPoint presentation with pictures from my trip. In my presentation, I talk about my personal transformation, what I’ve learned about elephants, and why it’s so important to protect them.

- Advocacy

- I create a “Save the Elephants of the Savanna” social network group where people can gather and share the latest updates, articles, and plan meetups and rallies.

- Inspired Action

- I create an online documentary video series that follows a herd of elephants on a harrowing journey across the savanna. Each elephant is given a name and viewers delight in each animal’s unique personality. I design clothing items that are emblazoned with each elephant and their names. The merchandise develops a fan base as people begin to identify with Abioye (the leader of the herd), Sabella (the wise mother), and Rab (the mischievous youngster). The documentary and clothing become a sensation, the proceeds go to protecting the elephants, and the public begins to appreciate just how precious these animals are.

Moving away from the elephants as an example, we can see the parallels of how this same experience can be true when sharing our learnings from customers with other product makers.

I can go on a site visit and spend time with a customer in Charleston, but I’d have the same difficulties convincing my team of the problems and frustrations with the product that I saw when I return to Seattle.

I could share a spreadsheet that has the number of times “Customer A” encountered an issue with the product, but that’s unlikely to move the team beyond awareness and understanding. To move toward inspired action and a sense of empathy with the problem, I can push to get teammates to go on at least one site visit with me or show videos of customers experiencing the issue and have them express how frustrating it is when they encounter it. Hearing about the problem in the customer’s own words can create a vivid story that inspires the team into action.

How Stories Affect Our Brains

A study conducted at Claremont Graduate University found that the brain releases powerful hormones when we watch videos of character-driven stories or in-person testimonials. In the study, researchers played a video for participants that showed an interview of a father talking about how his son was dying from a brain tumor. Blood was drawn before and after watching the video, and it was determined that there was an increase in oxytocin in the participants who had been exposed to the heart-wrenching interview. Oxytocin is produced in the hypothalamus and is responsible for social bonding, empathy, and generosity.

In fact, along with taking samples of the study participants’ blood, researchers also tracked how much money was donated to the foundation featured in the video. For the group that had watched the video, not only did their levels of oxytocin rise, but they also donated more money to the foundation compared to the groups that had not watched the video. Even more, the researchers could accurately predict the amount of money that would be donated, based on the levels of oxytocin that was in the participant’s body.5

Effectively, great stories have a profound effect on our brain’s chemistry, and they have the power to inspire us to action. As we begin to appreciate this, a simple question remains: what makes a great story?

The Patterns of a Great Story

In their book Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, Chip and Dan Heath deconstruct the most effective stories. In their research, they’ve identified that all great stories contain five patterns, each of which we explore in the subsections that follow.

Simplicity

Great storytellers break messages down to their essentials. They’re selective and only hold on to the parts of the story that matter. It’s surprisingly difficult to tell a simple story when conveying a complex idea, but it’s important not to overload your messages with too many ideas. If your message is complicated and multifaceted, you end up trying to communicate everything, and in the end, you communicate nothing. To have an effective message, break down complex ideas into singular, memorable ideas. Simple words and phrases to sum up larger more complex points make your stories sticky and memorable.

Unexpectedness

Great stories break the script. They bring new information to light in unexpected ways. Our brains are computers that thrive on collecting new and novel information, filtering out data that we’ve seen before. Today, our brains are being pummeled with more information than ever before. Emails, television ads, and app notifications produce an incredible amount of noise in the signal, and it can be very difficult for us to determine what information is worth paying attention to.

In a 2014 memo released to the public, Satya said, “We are moving from a world where computing power was scarce to a place where it now is almost limitless, and where the true scarce commodity is increasingly human attention.”6 We must find ways to cut through the noise and capture people’s attention. Breaking the script and offering data in new ways can be a great way to do that.

For example, a talented design manager named Jaclyn Shumate from our Office Media Group came up with a novel solution to share customer learnings with her team. Because her team was responsible for Stream, an enterprise-level video-sharing service, she decided to use the service to produce a video series much like a nightly news segment. With music, sound effects, direct clips from customer interviews, and a bit of humor, she created a fun and engaging way for her team to hear the latest round of customer feedback. By making sharing fun, she was able to capture the entire team’s attention and get them excited about learning directly from the customer.

Concreteness

Mission statements and messages that are intended to inspire change can often go awry if they feel ambiguous or abstract. Saying things like “empathize with your customers” or “create delightful experiences” can prove problematic when put into action. Our brains need concrete examples or tightly aligned analogies to break down complex messages into meaning that we can act upon.

Credibility

Any message or story must be backed with authenticity. Authentic stories help listeners trust the message. If your message or story feels like a platitude or an empty promise, discerning listeners will sense that. The best change agents are those who find ways to remain passionate about their mission. To maintain credibility, they’re always learning and looking for new ideas to help shape their company’s culture.

Emotions

Studies show that we remember the stories that move us. When a story gets us to feel something, whether it be inspiration or disgust, it has the power to get us to confront our own beliefs and behaviors. In business settings, we often shy away from talking about emotions. Particularly in North America, we’ve been conditioned to believe that “business isn’t personal.” However, if you want an organization that is deeply committed to delivering the best for your customers, you need to get comfortable with sharing your customers’ emotions. If customers are frustrated, don’t sterilize those comments. If a customer is cursing with frustration or slamming their fists on the table, make sure all the product teams see it. These emotions make the work we do real and are a potent reminder of the impact, negative or positive, that we all have on our customers.

Using Metaphors to Make Your Ideas Accessible

One difficult thing about working in DevDiv is that the situations we encounter with customers can be very difficult to communicate to people who are uninitiated with the technology.

For example, we were working with a team that was exploring opportunities for customers using Node.js, a runtime environment that allows developers to build applications. One of the things that makes Node.js unique is that it uses JavaScript, an incredibly popular programming language used by millions of developers. In a way, Node.js legitimized JavaScript as a language that could be used in highly scalable applications, proving that JavaScript was for more than just website development.

After talking with various Node.js customers, the team discovered that there were two primary customer segments. Both were still learning Node.js, but one segment already knew how to write code in JavaScript, and the other segment did not.

As we analyzed and synthesized the data from our interviews, the team went back-and-forth trying to articulate the similarities and differences between these two groups, which were numerous.

Finally, one of the program managers on the team said, “You know, it’s sort of like swimming. Developers who already know how to write JavaScript are like swimmers who are good at swimming in the pool. The developers who don’t know JavaScript can’t swim at all. Taking both types of developers and getting them to use Node.js is like throwing the pool swimmer and the nonswimmer in the ocean. The developers who know JavaScript can tread water, but now they’re encountering all sorts of new challenges, like a pool swimmer would encounter trying to navigate the massive waves and choppy water. The developers who don’t know JavaScript are like people trying to learn to swim for the first time, in the ocean! It’s hopeless!”

These types of metaphors, when accompanied by real customer stories, act as “shortcuts” and can help us empathize with another person’s experience. Expert storytellers help broader audiences understand complex ideas by relating the concept to an experience they’re more familiar with.

In his book I Is an Other: The Secret Life of Metaphor and How It Shapes the Way We See the World, author James Geary explains how metaphors and analogies help us generate empathy and understanding:

Analogy is the only way we learn about anything of which we can have no direct experience, whether it’s the behavior of subatomic particles or the content of other people’s experiences.7

Through our past experiences of learning how to swim, we could empathize with how it must feel to learn Node.js. It helped us appreciate just how difficult it would be for each customer segment to learn Node.js. Each segment had its own frustrations, but the amount of JavaScript they already knew helped us determine the intensity of those frustrations.

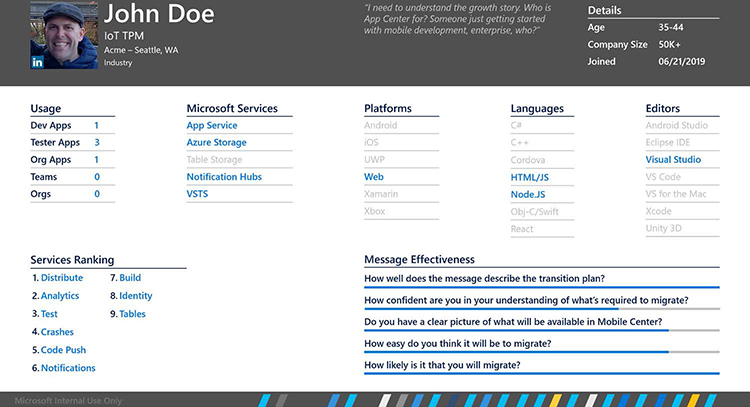

The customers we talk to offer us their real stories and unique perspectives. We can then take the responses of each customer and put them on a customer card (see Figure 7-2). A collection of these cards can represent an entire customer segment. In a culture that employs the power of customer voices, you don’t need to spend time designing a fictitious persona. Your team will be armed with customer profiles full of real customers the team has talked to.

Figure 7-2. An example of a customer card, combining data from product usage, survey responses, and direct interviews

Don’t Just Tell Them, Show Them

Like spoken metaphors, visual metaphors can also be a powerful way to communicate complex ideas. The adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” holds true, and every great storyteller thinks not only in words, but in pictures as well.

Although numerical data and statistics can bring credibility and authority, they also increase the chances that our overall message will become buried by calculations and normalizations. If we’re not careful, numbers can pull the human condition out of the stories that we want share. To get to the essence of any story, you need the “five Ws”: the who, what, where, when, and why.

Dan Roam, author of Blah, Blah, Blah: What to Do When Words Don’t Work, advocates using simple illustrations to communicate big ideas. Things like graphs, stick figure characters, smiley and sad faces, and sketches of everyday objects help us connect the storyteller’s message to concepts we’re already familiar with.

Roam promotes the use of a “vivid grammar,” which aligns the words in our stories to visual aids that can help make them more vivid.8

We were inspired by this and developed our own “vivid grammar” graph to be used in our workshops.

Table 7-1 shows how our version of Roam’s vivid grammar graph breaks down.

| Grammar | Visual |

|---|---|

| Who/what Person, place, thing, context |

Portrait |

| How much Some, few, enough, most, less, all |

Charts |

| Where Above, below, and, or, but |

Maps |

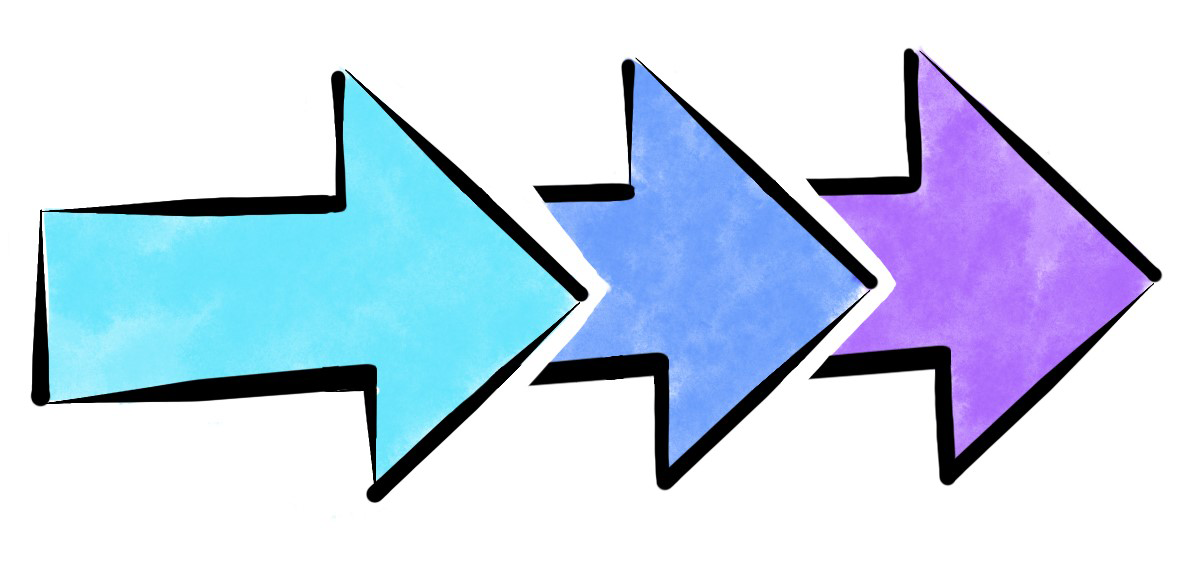

| When Before, now, later |

Timelines |

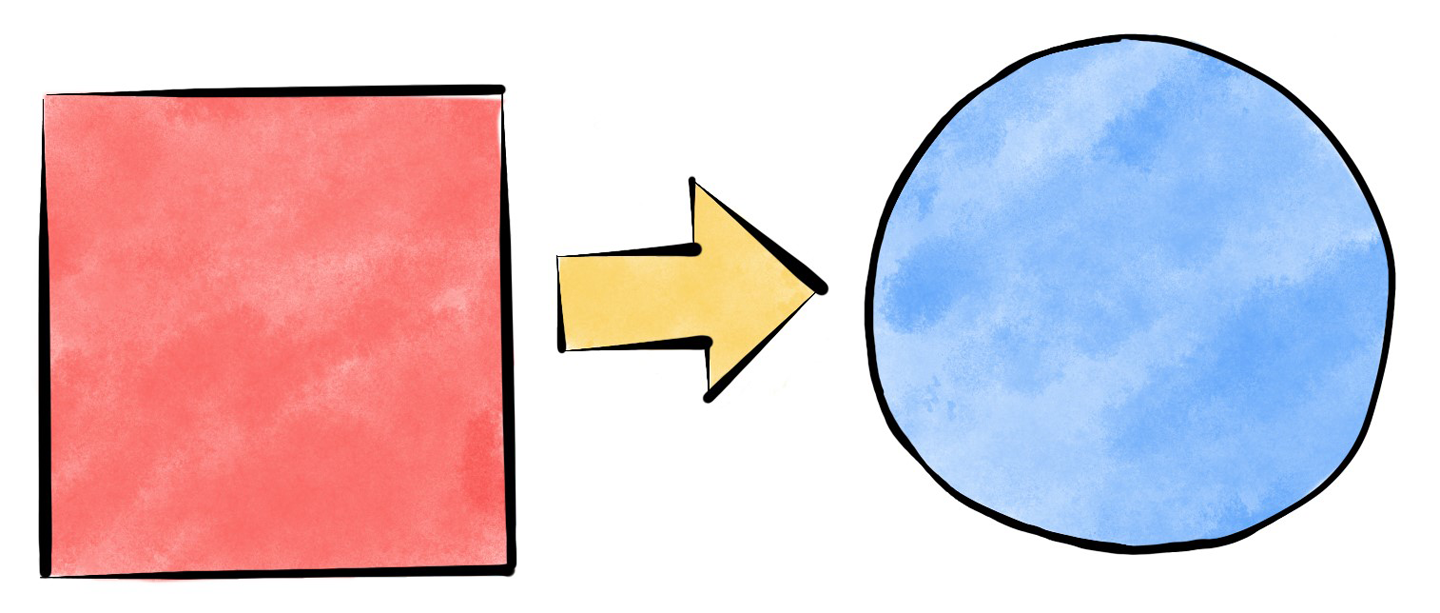

| How Simple relationships |

Flowcharts |

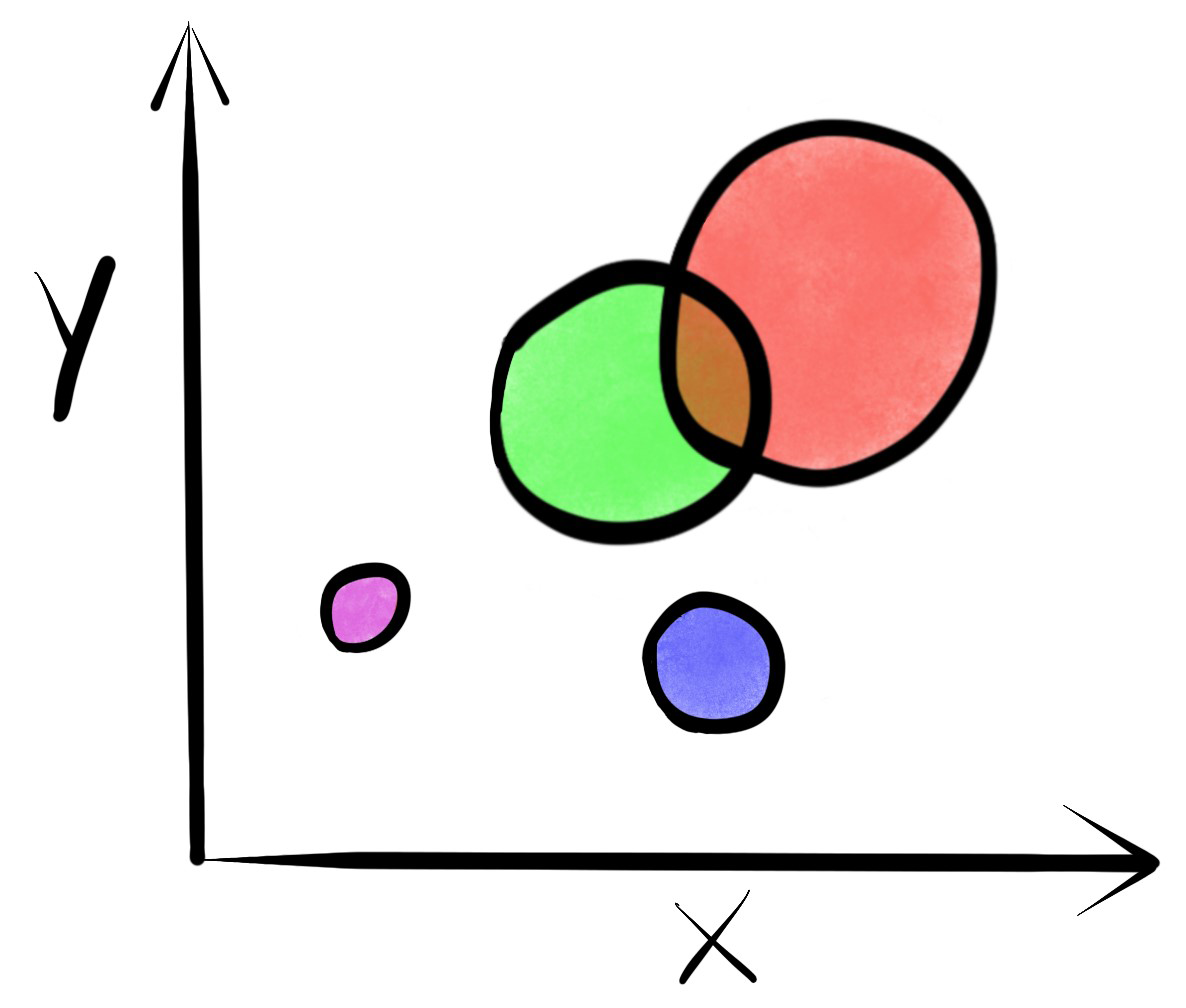

| Why Complex relationships |

Multivariable plots |

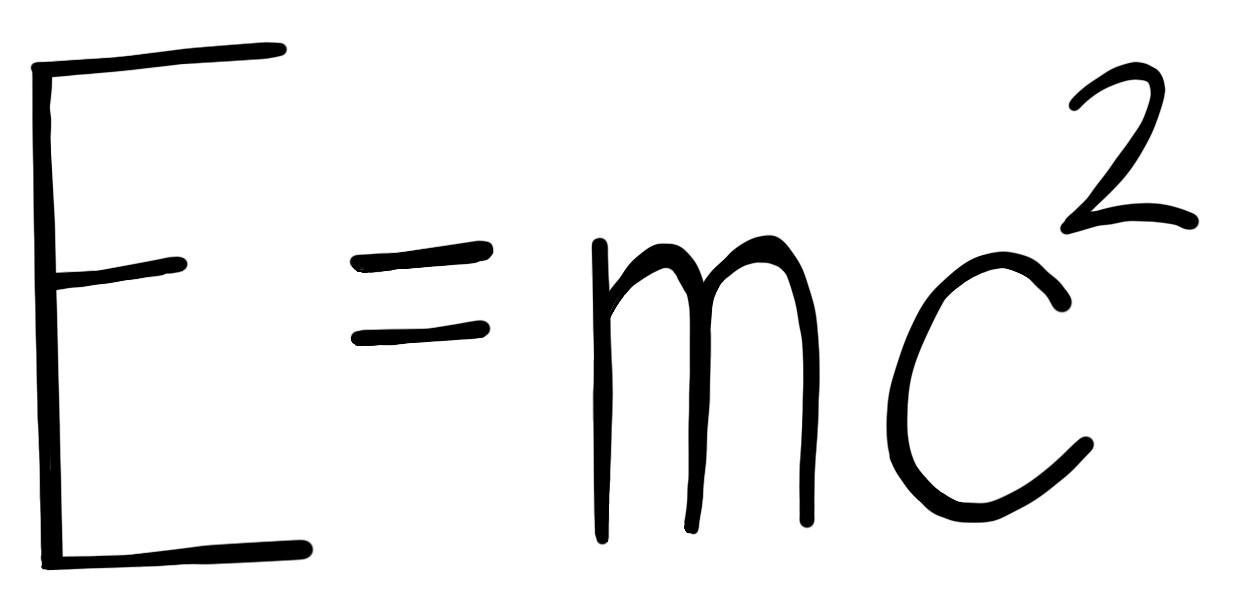

| Moral Key takeaway |

Equations |

Within this table, we identify the grammar, which is the type of story we’re trying to tell, and the corresponding visual element that helps us visualize that type of story. This has proven to be an invaluable tool when our product teams need to express what they’ve learned from their customers.

Let’s examine each grammar in detail:

- Who/what (nouns and pronouns)

- As we discussed earlier, a customer’s quotes, pictures, and other vivid information can be used to create a customer card. A collection of those cards could represent an entire customer profile. When customers participate in our research studies or give us feedback, we can ask for their permission to use additional resources like their LinkedIn profiles. Often, customers are more than willing to share this information given that it is available to the public anyway. These profiles can provide rich information that bring the customer to life for the rest of the team.

- How much (adjectives of quantity)

- When you’re dealing with quantity, it can be useful to take the time to plot the differences on a bar graph or pie chart. For instance, it can be useful to see how much money customers are spending to resolve a problem or how much time is required to learn a new tool. When these quantities are displayed visually, they can be powerful visuals that help teams understand the magnitude of their customers’ issues.

- Where (prepositions and conjunctions)

- When trying to communicate position, location, or how different ideas relate to one another, a map can be a valuable instrument to show those representations. Tension graphs that show how two needs are at odds with another (e.g., cost versus quality) can help teams appreciate the conflicts our customers face when making decisions to choose our products.

- When (tense)

- As you spend time learning from customers, it might become necessary to capture when an important event occurs. Timelines can help us chart our culture change journey or how a customer uses our products. For example, the team might benefit from seeing your customer’s experience plotted over a journey timeline. The timeline could show critical moments when the customer needs to interact with your product. A tool like a journey timeline can help illustrate the points in time when the customer experience of your product can be improved.

- How? (complex verbs)

- When you’re trying to illustrate what happened or how something occurs, flowcharts can be useful tools to visualize those procedural operations. Our customers can often live and work within complex worlds and relationships. For example, if your team works on collaboration software, it can be useful for it to visualize and understand how customers navigate their leadership chain to seek approval for project funding. The subtle nuances in how these customers collaborate within these contexts can surface valuable unmet needs for a team focused on organizational collaboration.

- Why? (complex subjects)

- If you’re trying to communicate why something is happening in your data, illustrations like multivariable plots can help visualize how different factors relate to one another and produce a particular outcome. For example, you might use a multivariable plot to show how variables like time, money, or prior investment affect a customer’s decision to try your product. Plotting these variables together can illuminate the strength, form, and dependence they have on one another.

- Moral

- Every story should have a moral or theme. It’s the “big idea” or shortcut that sums it all up. Earlier, we looked at the story of a team working with Node.js customers. They came up with the metaphor of pool swimmers and nonswimmers being thrust into learning how to swim in the ocean. The moral to the insight of that story could be as simple as, “Node.js is like learning to swim in the ocean.” These morals act as a sort of equation, helping you to create shortcuts to understanding by creating metaphors to more familiar experiences. Morals act as a tagline: an idea you can convey quickly, without having to unpack everything.

Consider the customer stories that are shared in your organization. Are they filled with numbers and statistics, or do you include in-depth customer stories and illustrations that help teams to understand your learnings? Are you finding ways to combine the power of quantitative data (numbers) with the emotion of qualitative data (direct customer observations, quotes, testimonials)?

In turn, consider your culture change movement. Are your stories of success consumed with training completion scores or pledge signups? Do you have rich, vivid testimonials from fellow employees that share their experiences with the new culture change? What are the morals of these stories, and what should your fellow employees learn from them?

Consider the Medium

Sometimes, it can be a slog to look at bland notes on a PowerPoint slide or read through a dense trip report. If you want teams to empathize with customers, consider delivering the information in novel ways. The “culture room” that we built for Satya’s visit (see Chapter 1) is an example of this.

Every time we bring someone new into the room, we delight in their reaction. We hear things such as, “I like how I feel in this room; it feels like I’m surrounded by great ideas.” Or, we hear, “Did you do something with the lighting in the room? I feel so alert and creative!” Now, even though we’re proud of the learnings shared in the room, I can confidently state that we had nothing to do with the lighting in the room.

What I think is happening during those visits is that people in business have become so used to receiving data in certain forms that it’s rare when they see something that breaks the script. Giving someone a presentation that takes over a physical room isn’t what they’re expecting. They’re expecting to sit in a darkened conference room, pleading with their eyes not to close.

So, if you’re having trouble sparking desired action for your latest initiative, you might need to consider how you’re delivering the learnings that support your project. Think of delivering your learning in ways that might break the mold of expectation. For example, we have had teams create “customer walls” with quotes from customer interviews or pictures customers have given us permission to use. They’ll be strategically placed in hallways so that team members can catch a customer story on the way to their next meeting. I always delight when I see a product team surrounding one of these installations, reflecting on our products and discussing ways to better serve our customers. Consider how you can feature your customer feedback in unexpected ways for your product teams. In effect, you want to surround them with their customers so that they see the impact they’re making as they go about their work. With your customers’ permission, you can take their feedback and showcase it by hanging posters in your hallways or pushing it out to screensavers or televisions in your building. This can create a visual experience throughout your offices that keep your teams connected to the customers they serve.

Vivid Stories Are Directly Proportional to Vivid Interviews

Our ability to tell vivid stories is directly proportional to our ability to conduct vivid interviews with our customers. In other words, if we’re not asking vivid questions, we cannot tell vivid stories. If we limit our interviews to closed yes-or-no questions, we will be left with a bunch of data but no stories to share.

For example, suppose that I’m doing an investigation into how people respond to a new dashboard we’re designing in a car. I could take a group of customers who have been using the revised dashboard and ask them simply:

Do you like the new dashboard?

We could imagine a variety of simple responses. Customers might say things like, “Sure. It’s good,” or, “No. It’s confusing.”

I could close our study and report on the number of customers who liked the new dashboard versus the number of customers who didn’t like it. Of course, the next logical question the team might have is, “Why did they like or dislike it?”

By asking open-ended questions, we can help customers give us much more vivid information about their experiences. We can ask questions like these:

What has your experience been like using the dashboard?

When was the last time you configured a setting on your dashboard? What was the experience like?

How often would you say that you use the dashboard?

What components of the dashboard are most important? What components are the least important?

What motivated you to configure the dashboard?

Would you recommend the new dashboard to a friend? Why or why not?

If you were able to change one thing about the dashboard, what would it be?

These questions allow the customers to tell us a story that highlights their personal motivations, their frustrations, and their desires. As customers respond, we continually ask them to tell us more.

Open-ended, vivid questions help our customers reflect on their experiences, think deeply about how our products affect them, and give them permission to challenge us and tell us how we can improve the experience for them.

The answers they give us to these questions give us the anecdotes that we need to bring their stories and experiences to life.

Steve Portigal, author and user research consultant, says that your goal is to move your interviews from “Question-Answer” to “Question-Story.” He suggests that, by continuing to ask follow-up questions and digging deeper into your customer responses, you will help customers share their personal experiences.9 You’re also building a rapport and a relationship with the customer, getting to know who they really are.

In just about any engineering review, you’ll hear Julia Liuson, John Montgomery, or Amanda Silver ask questions like: “What customers did you talk to?” “What did you ask them?” “What did they have to say?” Our leadership team is trying to grasp the bigger picture. They’re asking for the story. Teams have learned quickly that they need to be armed with these stories in order to communicate how a change in a product or service will affect our customers.

As you’ve seen throughout this book, the same can be said of the stories you share around your culture change. Asking employees rich, vivid, open-ended questions is a great way to get to the heart of their stories of change. These are the details that inspire others to enact the three vital behaviors of change (awareness, curiosity, and courage). Seeing stories of employees succeeding with the new cultural values can motivate others to engage and participate.

Author and cognitive neuroscientist Tali Sharot says that “People observe not only your choices but also the consequences you experience as a result of those choices. This is why behavior has widespread consequences—it affects not only the person being praised or critiqued but also everyone else who is watching.”10

Applying the Hack

Here are some ways that you can make your data more relatable:

-

It’s important that your teams’ vivid customer stories become part of everyday conversation. Resist the urge to hold onto customer feedback in favor of an extensive report.

-

Consider taking a creative writing course or studying the key elements of storytelling. Practicing these skills can have a huge impact in communicating culture change. Study other great storytellers in your organization or industry. When you see their stories, what captivates you? How do they get your attention?

-

Look over the ways that you share customer information. Are your customers just nameless numbers and statistics? If so, make time to feature the faces and voices of real customers. You can do this through video, presentation, inviting them to visit the team, and many other methods. The point is to connect the team with the real people they serve.

-

As you and your teams collect customer stories, look over them and consider how they can best be used to inspire others. Often, you’ll find ways to use a great story in multiple venues (e.g., staff meetings, division-wide newsletters, product presentations, etc.).

-

Dedicate a wall in your team room as the “Customer Wall.” This can be a space where the team hangs pictures, quotes, interview notes, or any other learning about the customer. It can be a creative way for everyone to participate in customer learning.

-

Focus on telling the complete story. Don’t just focus on sharing how your customer is using the product. Share with them who the customer is. Don’t forget to include vital learnings like what motivates them, what frustrates them, or what they value. A customer isn’t just a user of your product; they’re a human being with emotions and a story. Be sure that your teams capture those vivid elements.

-

How visual is the story you’re trying to tell? Are you relying only on text and numbers? Pictures, graphs, and flowcharts go a long way in simplifying complex stories.

-

Write a summary paragraph of your learnings from customer interviews. Then, condense those findings into two sentences. Then, a single sentence. Finally, a single word. Try expressing your big ideas in multiple ways, long form and short.

-

Always consider your audience. Each time you tell the story of your customers, there will be something meaningful for each group you meet with. Before each meeting, review your work and ask yourself, “What will this team or person care most about?” and devise a way to get those things as soon as possible.

-

Try “breaking the script” by delivering your findings in novel and unexpected ways. Instead of an emailed report, perhaps you can design a wall just outside your leadership team’s office. Make it visual and colorful. Experiment with scale and space. Record a “breaking news” video in the format of late-night news, flashing on the latest customer interviews. Break people out of their day-to-day expectations to gain their attention and interest.

-

If you’re dealing with a complex idea, consider aligning your points to a concept that is more accessible and familiar. Imagine that you’re explaining your work to your grandparents. What analogies would you use to help them understand what you’ve learned?

-

Bring energy to your storytelling! Your audience will feed off the energy you give. If you’re passionate and excited about what you’ve learned, let that show through.

-

Don’t be tempted to paraphrase or summarize customer reactions. Saying things like, “Customers really hated this,” or, “Nobody noticed it,” creates too much distance between the team and the customers’ emotions. For example, sharing a quote from a customer that says, “You know, I really loved this product until you introduced this new change. Now, I’ll never use it again. You’ve lost me as a customer,” is far more powerful than simply saying “customers really don’t like the new feature.”