Chapter 6. Meet Teams Where They Are

Voltaire once wrote, “The best is the enemy of good.” Or, put another way, we shouldn’t let perfect be the enemy of good enough. This can be so true when we consider how we go about promoting culture change.

I’ve seen so many change agents become frustrated because they can’t influence their teams to change their behavior, but they propose an all-or-nothing approach. You’re either all in or all out. The truth is that change can’t always be that simple. Product teams will find themselves caught between two cultures: the one that is rooted in the values from before and the one that’s being built on new values going forward.

Change is a hero’s journey in which we leave the status quo, are confronted with trials and tribulations, and return forever changed by our experiences. It’s during these trials and tribulations when our anxiety is highest. It’s when we’re most likely to doubt our abilities and second-guess our direction.

So if we’re in the business of encouraging cultural change, we must realize that we should be in the business of making change less difficult. That requires us to apply the hack of meeting teams where they are.

In this chapter, we discuss the power of pragmatism and how giving over some ground is actually one of the best ways to encourage others to join you. It’s not that we should give up our principles or change our cultural vision, but we must understand that we will need to meet people in the context of their current world, not the world as we would like it to be.

Agents of Change: Dr. Wiwat Rojanapithayakorn

In 1993, the Department of Disease Control in Thailand was facing a shocking epidemic. In just three years, new reported cases of HIV infections had climbed by a factor of 10, from 100,000 to a staggering 1,000,000.

Health officials were scrambling to understand the cause. Intravenous drug use and the sharing of needles was part of the cause, but experts believed the growing number of sex workers was the most significant factor. In fact, they believed that 97% of all cases of HIV were linked to sexual transmission from sex workers.1

The government was in denial about its growing sex industry and had tried numerous ways to contain it. It tried to address the problem from the “supply side” by cracking down on brothels, but for every brothel the government closed, another popped up. It tried from the “demand side” by going after men and tourists who were flooding the region. That too had little effect.

At the time, Dr. Wiwat Rojanapithayakorn (Dr. Wiwat) was serving as the director of the Office of Communicable Disease Control in Ratchaburi. From his research, Wiwat was convinced that unprotected sex was the most critical behavior that was causing the epidemic. He posited that if they could get 100% condom use within the industry, they would see dramatic results. This was no easy proposition. With the government in denial, it was not looking to find ways to further promote sex work. The thinking was that by instructing the public to engage in safe sex with sex workers, the government would be promoting this illegal behavior.

The numbers were climbing, and Wiwat was horrified to see HIV spreading from community to community. He believed that if they didn’t act immediately, Thailand was on the path toward leading the world in HIV infections per capita.

He concluded that the best way to combat the issue was to educate the public and sex workers about the benefits of safe sex. HIV was a behavior-based infection; it was a result of people engaging in behaviors that increased their chance of infection. So he decided to focus his team’s efforts on increasing a single vital behavior: condom use.

This was a controversial stance given that many in the public felt that it was putting a small bandage on a severe wound. They believed that it would be far more beneficial and lasting if they could abolish the sex industry altogether. They favored responses that called on society to improve its morals surrounding the issue.

Additionally, men preferred sex without a condom, and brothels were much more willing to provide what their clients wanted over protecting the health and safety of their workers. Wiwat knew that it was an all-or-nothing deal. If only some of the brothels enforced condom use, the other brothels could compete by not using them. For this to work, owners of sex establishments needed to all agree on enforcing condom use. This was also a hard sell because he knew it could be economically damaging to the brothel owners’ businesses.2

It took courage, but Wiwat and his team pressed forward. They decided they would run an experiment in the Ratchaburi region. They worked with the local police, mayors, and the owners of sex establishments. Their message was simple—they wanted to encourage 100% use of condoms among the sex workers. The vital behavior was scripted: “No condom, no sex.” Condoms were freely distributed, and brothels were asked to make it a requirement that clients used them. Brothels that failed to comply would be shut down by the authorities.

In two short months, the team was shocked by their results. New cases of sexually transmitted infections fell from 13% to 1% in the Ratchaburi region.3

Encouraged by the experiment, the team began to roll out the “100% condom use” campaign throughout Thailand. It used an all-out media blitz, playing commercials that promoted safe sex and warned the public about the devastation of AIDS. The team had the commercials running every hour on the nation’s 488 radio networks and 6 television networks.

But distributing the condoms and playing advertisements on the radio wouldn’t be enough. Wiwat and his team needed to coach sex workers on how to deal with situations in which clients didn’t want to use a condom. They trained women who had more experience in the industry, and in turn, those women coached and mentored the younger women. They would role-play various scenarios and practice how to deal with them, getting feedback and refining their approach. Essentially, the team was building leaders within the sex worker community who promoted their protection. These women quickly became influencers and helped younger women advocate for their own safety.

“You must get someone who has done it to teach. I can stand up and teach negotiation skills all day and have no effect,” says Mechai Viravaidya, a former politician and activist for family planning and AIDS awareness in Thailand. “If a sex worker is having a difficult time negotiating with a customer, she would go get the more experienced girl to help. Two-on-one negotiations are much simpler.”4

Compliance with the nationwide program spiked as condom usage rose from less than 25% to more than 90%. Although effecting the change across the entire country took more time than the smaller Ratchaburi region, the team still watched with astonishment as new reported cases of sexually transmitted infections dropped 14% in 5 years and 80% from 1991 to 2001. The World Bank estimates that Wiwat and his team prevented at least 200,000 cases of AIDS in that time period, concluding that it was an “accomplishment that few other countries, if any, have been able to replicate.”5

What makes Wiwat’s example so poignant is his laser-like focus on one vital behavior. When dealing with complex problems, it can be tempting to employ a scattershot approach, trying multiple things and seeing which one sticks. It must have been very difficult for the team to not become swept into trying to help these women in ways that could reduce their dependence on the work in the first place.

They could’ve tried to appeal to their moral obligations, shaming them for engaging in such explicit behavior. Instead, they decided to meet the brothel owners and sex workers where they were. Like it or not, these people engaged in the business because it was a way to make money and survive. So they appealed to their economic interests instead. From an economic standpoint, engaging in unprotected sex was simply bad for business. It resulted in the death of workers and time off to treat undesirable infections. It was a difficult but pragmatic decision that ultimately saved thousands of lives.

The Family Health Institute speculates that “perhaps the main reason for the campaign’s success was its concentration on a limited objective—the consistent and widespread use of condoms in commercial sex—rather than on wider goals, such as eliminating sex altogether, or the improvement of public morality.”6

Be Passionately Pragmatic

When bringing about a culture change, results come to those who are willing to be pragmatic and temper their radicalism in favor of making change digestible to those whom they are trying to influence.

This can be incredibly difficult for change agents because they are often the ones who are deeply passionate about and committed to the mission of change. In these cases, they often are their own worst enemy because they begin to resent or demonize those who are not changing quickly enough.

In the early moments of our journey of change in DevDiv, our team had many stumbles as we determined which behaviors we most cared about. It was easy to get specific and prescriptive about the customer-driven behaviors we wanted to see, and when we weren’t careful, we were auditors rather than multipliers.

For example, in the early days, we were rigid in our thinking of how the HPF should be used. We had a strong desire to see teams use the hypothesis templates exactly how we designed them.

For instance, the hypothesis template for each stage began with the words “We believe.” I remember advocating very strongly that every hypothesis should begin with those words because it would encourage teams to own their assumptions.

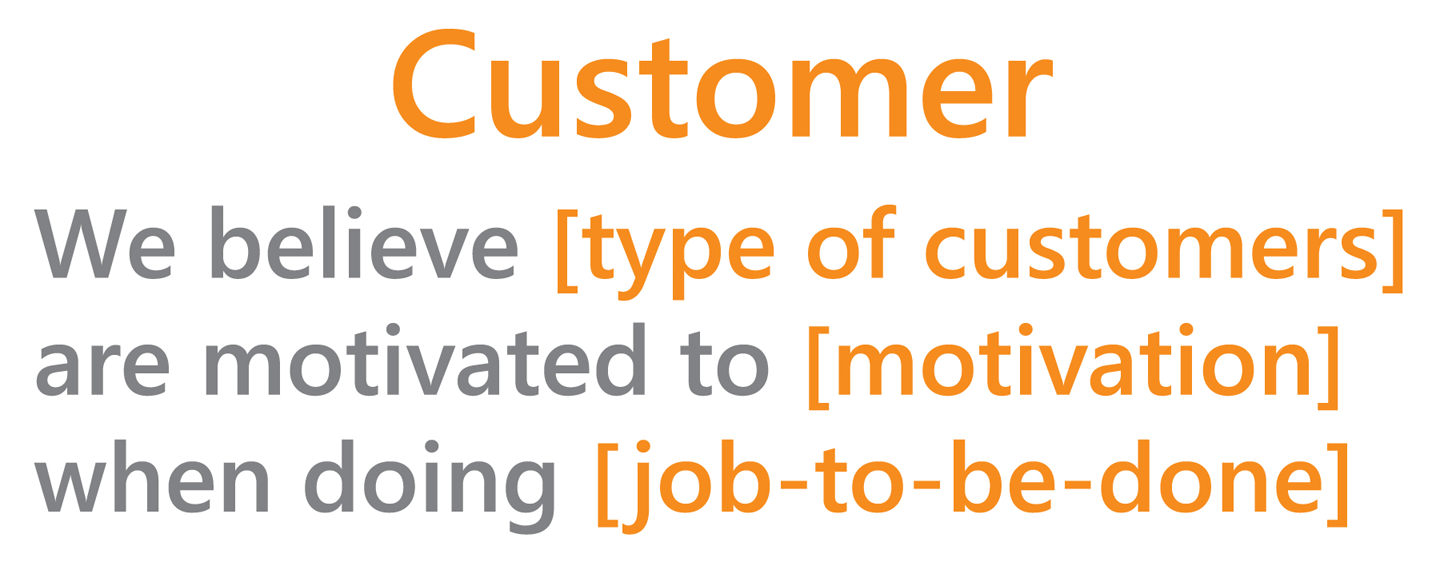

Over time, I realized that teams were far more receptive to using the framework when I presented it pragmatically rather than dogmatically. I began to appreciate that the framework worked better when teams embraced it and made it their own. Therefore, I relaxed on the pedantic details and “syntax” of the hypothesis and saw value in focusing teams’ attention on the parameters of the hypothesis templates (e.g., [type of customers], [motivation], [job-to-be-done], etc., as shown in Figure 6-1). This made the framework far more approachable and easier to immediately use, regardless of where teams were in their product life cycle.

Figure 6-1. Hypothesis template for the Customer stage with parameters for type of customers, motivation, and job-to-be-done

It became clear to us that program managers and engineers were much stronger at creating lists. We could have them generate far more hypotheses if we focused less on the overall syntax and honed their focus on generating lists full of the various parameters.

So we adjusted our approach and began saying, “The template is a guide to get you started. It’s not a requirement that all your hypotheses read like this, but the one thing you want to ensure is that you have at least captured these parameters.”

This had a dramatic effect on people’s willingness to try our approach. As one colleague remarked, “You’ve made it deceptively simple. You’ve broken the bigger task (formulating a hypothesis) into a smaller, more addressable task (creating lists of parameters).”

The value of consistency became less important than the value of adoption. We focused on the things that mattered (the parameters) and less on the things that didn’t (the overall syntax).

In DevDiv, I’ve often joked that we’re “passionately pragmatic.” We want you to be customer driven, but we want you to want to join us, not feel like you were “voluntold” to do things our way. This was a point of view that we grew to appreciate the more we tried to influence teams and met resistance. Just like Wiwat’s team, we were tempted to address myriad behaviors, but writing hypotheses was the behavior that unlocked all three of the key vital behaviors: awareness, curiosity, and courage.

By formulating hypotheses, teams generated awareness of their assumptions, which sparked curiosity to experiment and validate or invalidate their hypotheses. It also gave them the courage they needed to accept the data, even if it suggested they needed to pursue a new direction.

It became clear to us that writing hypotheses was the on-ramp to other behaviors: creating discussion guides, talking with customers, and triangulating data by cross-referencing interviews (qualitative) with our telemetry and analytics (quantitative). These behaviors were a result of getting the teams to understand and appreciate the benefits of hypothesis generation and experimentation.

Encouraging Pride of Ownership

When teams make the process their own, they have pride of ownership and the feeling that they own the direction their team will take. Whichever strategy they employed, the only requirements were that they had hypotheses to communicate what they were trying to learn and that they used customer data to determine whether it was validated or invalidated.

The Customer-Driven Playbook and the HPF both represented an approach that allowed teams the flexibility they needed to make local adjustments, but they also provided a roadmap for how to ensure they remained aligned to the global goal of customer obsession. We gave teams autonomy to make the decision. They couldn’t refuse to talk with customers or generate hypotheses, but they didn’t need to use the hypotheses templates if they didn’t want to.

But, as more and more teams saw people succeeding with the framework, it seemed like a no-brainer to use that approach on their own projects. We didn’t mandate its usage or penalize groups that didn’t use it. They willingly chose to use it for themselves.

That choice makes all the difference in creating lasting culture change because it gives them the autonomy to chart their own course and the challenge to master a new approach. Autonomy and mastery have both been proven instrumental in creating the motivation that’s required to change one’s behavior.

Autonomy and Mastery

On June 26, 2014, the New York State Court of Appeals, the highest court in the state, issued a 20-page opinion on a controversial proposal to prohibit the sale of sugary soft drinks in cups larger than 16 ounces (473 ml). The court decided that the proposal “exceeded the scope of its regulatory authority” and effectively killed any hopes that New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg and his team of health advocates had in reducing soft-drink purchases to fight the obesity epidemic within the city.7

Although Bloomberg was disappointed with the ruling, he maintained a brave face and remarked that it was a “temporary setback.”8 As far as his team was concerned, public health was a signature issue. In a four-month time period, the city had lost two thousand residents to diabetes. To them, the ban wasn’t a controversial issue, but a necessary evil to prevent a drain on the state’s healthcare system and to save countless lives.

Critics were concerned that the proposal contained too many loopholes and exemptions. For example, it wasn’t OK for local theaters or restaurants to sell soft drinks larger than 16 ounces, but nationwide chains like 7-Eleven could maintain their “Big Gulp”–branded cups that came in at 64 ounces (1,892 ml). There also wasn’t a ban on refills. Additionally, it was unclear what constituted a “sugary drink.” Starbucks, for example, was exempt even though many of their blended coffee drinks contained excessive amounts of sugar. This left local business feeling the burden of competing with one hand tied behind their back. The American Beverage Association took the proposal before the courts, calling the ban “arbitrary and capricious.”9

Beyond all that, the biggest problem was that many citizens simply weren’t in favor of the proposal. Critics started referring to New York as the “nanny state,” citing that Bloomberg’s proposal suggested residents couldn’t make their own choices about the food and beverages they consumed. It treated them like children who had to have their toys taken away because they couldn’t be trusted to make the proper decisions.

The opposition from New Yorkers spanned political leanings, race, and gender. According to a study conducted by the New York Times, 6 in 10 residents thought the ban was a bad idea. They felt that the ban overreached, infringing on their right to make their own choices, even if those choices were potentially bad for their health.

In our desire to see change happen more quickly, it’s tempting to speed things along by applying punitive pressure. However, when we do this, we welcome rebellious confrontation as employees dig in their heels and resist change.

Additionally, mandating or enforcing a behavior change can have unintended consequences. As an example, research has found that schools that engage in a “zero tolerance” policy, indiscriminately suspending students who are involved in fighting, end up disproportionally punishing students of color and students with disabilities.10

There’s an old saying: “You’ll attract more flies with honey than vinegar.” And it rings true when you’re trying to attract employees to engage in new behaviors. The goal of meeting people where they are is to leave them feeling empowered rather than punished by the new culture.

In his book Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, author Daniel Pink outlines the science behind our brains and motivation. If employees feel like they are being compensated fairly and have access to good benefits, it can be difficult to find new ways to motivate them.

However, Pink and many other researchers believe that beyond the essentials, employees want to feel that their work matters, that they have the freedom to apply their own creative thinking to problems, and that they have the ability to create new skills that can help them well into the future. It doesn’t cost money to give this to employees. However, it does require patience, flexibility, and a growth mindset from organizational leaders and change agents.

Just-in-Time Coaching

As we discussed earlier in the book, during our workshops, we create purpose by giving each team a business goal that is relevant to their product area. Other than that, we don’t prescribe exactly how they should go about solving that problem. Throughout the week, we slowly introduce tools like the HPF, discussion guides, interviewing techniques, sense-making, and concept-value tests. With each new tool we introduce, we spend very little time giving a lecture and instead try to put the tool in participants’ hands as quickly as possible.

Initially, workshop attendees have a strong desire to have you just show them how to complete the task. However, we help them realize that, for our tools to be meaningful and useful, they must try them within their own context.

During one workshop, one of the participants became quite frustrated with me. I had just introduced the notion of using storyboarding to tell the story of an idea. The goal was to give teams time to try storyboarding to express their ideas using a different medium (sketching and storytelling). After briefly explaining the value of storyboarding, I handed out a worksheet for teams to start creating “keyframes” of their stories.

The participant held up the handout, frowned at me and, slightly perturbed, asked, “Can you just tell me what you want us to do?”

“Sure,” I replied. “This handout represents three frames of your storyboard. You can fill out these three frames or more if you need them. Use these frames to express what your idea does and how it might impact the customer.”

“No, I get that,” the participant curtly responded. “I just want you to tell me what this should look like by the time we’re finished with this exercise.”

“I have no idea,” I admitted, “but I’m 100% committed to helping you figure out what it could look like.”

I decided to reset the conversation. “Why don’t you tell me where the team is at in their progress?”

As the participant updated me on the team’s progress, it became clear that she was anxious about not getting enough time to complete the previous exercise. They were exploring all the various problems they could solve for the customer, and she felt like there could be more underlying problems. She felt it was too soon to move on to storyboarding ideas because the team needed more time to think about its customers’ problems.

I quickly pivoted. “OK. So it looks to me that storyboarding won’t be useful right now.” I slid the storyboard handout to the side of the table and said, “Let’s not use it then. We can use it later, if we think it can help.”

We then had a fantastic discussion about the problems the team was exploring and, eventually, those ideas transitioned directly into the storyboarding exercise.

Earlier in my journey as a workshop coach, I would’ve handled that situation poorly. I would’ve seen the participant’s resistance to the storyboarding exercise as her not appreciating the value of the approach. I would’ve spent time trying to convince her, feeling pressure to keep the team on task for the next exercise. It would’ve turned into a battle of wills, and it would’ve gotten us nowhere. I would’ve been frustrated, and I would’ve lost a chance to connect with the team.

I’ve since learned, through much trial and error, that if I relax my approach, resist getting defensive, and work hard to help others find their own personal value in our tools, it tends to leave us both in a better position, bonded in mutual respect and understanding.

As a coach in our workshops, my job is to put our tools in front of product makers and then work hard to help them find value in those tools as they begin to apply them to their work. I must remain flexible and gently steer teams toward a meaningful direction. Every step of the way, I’m going to check in and ensure the team is getting where it wants to go.

If you’re a trainer, facilitator, or coach, you should consider a similar approach.

Feeling stupid or coerced can leave team members feeling diminished. Create room within your programs to give people a sense of freedom and an ability for them to make it their own. Empower them by helping them feel smart and productive, giving them a feeling of ownership and a challenge to master new cultural behaviors.

In the New York Times bestselling book Influencer: The New Science of Leading Change, the authors write:

You must replace judgement with empathy, and lectures with questions. If you do so, you gain influence. The instant you stop trying to impose your agenda on others, you eliminate the fight for control. You end unnecessary battles over whose view of the world is correct.11

Find the Quickest Pathways to Learn

When beginning your journey in building a customer-driven culture, it’s easy to be overwhelmed with all the decisions that you need to make and training programs you need to get started. It can be tempting to try to answer all of the questions of how you will scale your initiatives before you even start.

It can be easy to become blocked by another department or your engineering team while you wait for the perfect time to get started engaging your customers. Also, while you’re trying to navigate your organization, looking for permission to investigate a new business opportunity or connect with a customer, a small startup with a completely flat org chart is inventing the next disruption to your industry.

One of the questions we get a lot is: “How much data should we collect before we make a decision?” The unfortunate answer is that it depends. We always say collect as much data as you can, as quickly as you can, to make an informed decision on where to go next.

You’ll never have perfectly complete data. There will always be gaps, so you do the most learning you can to make your next decision. Determining how comfortable you are with those gaps in knowledge depends on your risk tolerance for a given project. The riskier your decision, the more information you’ll require, which in turn will require you to collect more customer data and feedback. Promoting a customer-driven culture isn’t about pursuing absolute certainty. It’s about de-risking your decisions as quickly as possible by taking advantage of the behaviors and feedback of your customers as strong data points in your decision-making process.

In every decision you make, you want to be asking yourself, “What is the fastest way to test your assumptions regarding this decision?” In his book The Lean Startup, author and entrepreneur Eric Ries refers to this rapid learning cadence as the Build, Measure, Learn Feedback Loop. Essentially, it starts with a “leap of faith” or an assumption. You formulate that into a hypothesis, run a lightweight experiment, analyze the results, and then iterate on your idea based on what you’ve learned.

Although his book envisioned the feedback for fast-moving startups, we’ve found that the same Lean methods work irrespective of company or workgroup size. The goal is removing waste and bureaucracy in your processes, regardless of whether you’re doing foundational or directional research.12

For example, if you’re trying to determine where a button should be placed in your application (directional research), you’ll want to run small, self-contained experiments that are intended to answer that very specific question. Things like usability studies with a small collection of participants or A/B testing within your products can be ways to achieve this.

Conversely, foundational research is required when you’re trying to learn about customer trends, motivations, unmet needs, and other wide-ranging details from your customers. Typically, these learnings can come from direct customer interviews, site visits, or focus groups. These can take more time and planning compared to directional research.

However, if your team is engaging in both types of learning, in parallel, you can move much more quickly. For example, if you’re bringing in customers for a usability study, it’s also a great opportunity to have a brief conversation about the problem space and the various tasks they engage in and to ask them about their motivations and frustrations. Breaking down your research goals and optimizing them for the quickest pathway to learning allows you to create a plan that extracts the most out of your time with each customer you engage with.

As a change agent, it’s your job to remove any barriers that prevent people from learning and growing. Being rigid and putting up safeguards or barriers that prevent teams from accessing the data they need can be a surefire way to hinder any change effort.

You should look over your org chart. Are there departments or policies that create roadblocks for product teams to access their customers? If a member from a product team wanted to talk to five customers within their target demographic, how long would it take? Hours, days, weeks?

You certainly don’t want to bombard your customer accounts with a mountain of inquiries from your product teams; it’s understandable that you might want to put a buffer there. However, that buffer shouldn’t come at the cost of your product team’s ability to connect with and learn from its customers. You’ll need to seek the appropriate balance that fits your organization and your customers. Our experience is that customers genuinely appreciate being asked for their feedback. If you’re making a product for them that they rely on, typically they have a vested interest in helping make it better. If you’re finding it difficult to locate customers who are willing to talk with you, you might need to consider creating gratuity programs that give customers an incentive to make time in their busy schedules to connect with you. It doesn’t always need to be in the form of monetary compensation, although that does help. You can offer additional product support, discounts on additional features or accessories, or early access to the next version of your product.

You can also consider a program in which account managers connect the customer to the product team in a structured setting. Getting your sales or accounts teams involved in creating your feedback loop not only takes advantage of the strong customer relationships your sales teams have created, but it’s also a great way to get your product and sales teams to regularly collaborate.

Empathize with Your Enemies

As we seek culture change within our organizations, we will be met with countless obstacles, political maneuvering, and perhaps even inaccurate claims about our true motives. Successful change agents see these obstacles as opportunities to find common ground. The following true story is an example of this.

Agents of Change: Volpi Foods

In 1898 John Volpi traveled from his home in Milan, Italy, to the shores of America, bringing with him a centuries-old European tradition of dry-curing meats. His vision was to start his business by offering handcrafted dried meats to residents and families.

In 1902, he opened Volpi Foods in a small St. Louis neighborhood known as The Hill. He offered dried salami that was small enough to fit in the pockets of the local clay miners. The product was a hit, and Volpi’s business became a mainstay in St. Louis.

Today, Volpi Foods has been in operation for more than a century, distributing its handcrafted Italian meats in grocery stores throughout the United States. Lorenza Pasetti, John’s great-niece, eventually became the president of Volpi Foods, continuing the family tradition.

One year, while away at a foods show, Pasetti received a frantic phone call from a staff member back at the St. Louis office. According to the employee, they had just received a copy of a letter that had just been sent to Costco, one of Volpi’s biggest retail customers. The letter was from a US attorney representing the powerful Consorzio del Prosciutto di Parma, one of Italy’s global enforcers of food trademarks.

Essentially, the Consorzio claimed that Volpi was violating the law through its use of words like “traditional” and “prosciutto” on its labels. The organization believed that Volpi was not using traditional methods, which triggered an investigation from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA). For a company that prided itself on its reputation for maintaining its traditions and handcrafted quality, these charges were devastating.

“The letter denounced our prosciutto product and charged Volpi with infringement of US label law,” Pasetti explains. “This situation was nothing short of a crisis—and it attacked Volpi’s reputation, one we had built over a century.”13

If it was determined that the Consorzio’s claims were true, Volpi would be forced to remove words like “Italian” and “Proscuitto” from its packaging. This would require Volpi to abandon its entire identity, leaving it unable to compete with the growing US demand for specialty and authentic meats from Italy. The company’s future would be doomed under these restrictions.

Pasetti was at a loss for what to do next. The company was doing well, but it wouldn’t be able to sustain the cost of a long legal battle. After contacting the USDA, she found that the agency was starting to backtrack on its previous clearances of the company. Costco was concerned that it might face a class action lawsuit for carrying products that mislead consumers regarding their authenticity and thus was considering removing all Volpi products from its shelves. Things were unraveling quickly.

Pasetti decided to take a moment and consider the situation. She needed to understand where the Consorzio was coming from. Rather than remain incredulous to the claims that their products were inauthentic, she decided to research the Consorzio’s position.

She went online and learned that the Consorzio’s mission was to ensure that when companies labeled their products with words like “Italian” that they were adhering to the traditional Italian style of food making. Although she believed the Consorzio had unfairly targeted her company, Pasetti could still empathize with its mission. She agreed that, if anyone could claim their products were made with traditional Italian methods, it would diminish the reputation of the craft. In the end, the Consorzio was trying to maintain the quality of Italian traditions; this was a good thing for the entire industry. For companies like Volpi, putting the word “Italian” on its products was a source of profound pride. The Consorzio was working hard to ensure that it stayed that way.

Armed with this insight, Pasetti decided to set up a meeting with the Consorzio. She believed that if she could get in front of them and tell the story of her great-uncle’s company, they would realize that Volpi valued Italy’s traditions just as much as they did.

That summer, Pasetti found herself in front of the Consorzio in the northern Italian city of Parma. Sitting across from her were two Italian businessmen, twice her age. Through the meeting, she told them about Volpi’s heritage, how John, her great-uncle, had a dream of bringing the best of Italy to American families. She walked them through their process, spending time and detail on how they prepared their meats at scale, but still adhered to the Italian traditions and craftsmanship. Because Pasetti understood and deeply empathized with the Consorzio’s mission, she was able to meet them where they were. She could speak to their values and show them that they were partners, not enemies. She helped them realize they shared a common language and a common passion for the quality and precision of traditional methods.

The meeting worked, the two men were convinced, and the Consorzio retracted all of its claims.

By taking a moment to consider the Consorzio’s position and truly empathizing with it, Pasetti was able to speak to the representatives in a way that showed she understood and valued what it was trying to do. Through empathy and understanding, she avoided years of costly court battles. She might have been justified in fighting back, but the approach of seeking understanding and a commitment to meet the Consorzio on their claims and positions proved to be the best course of action.

Melting the “Frozen Middle”

When pursuing a culture that is focused on the customer, it’s a mistake to assume businesses will shift their processes because it’s the right thing to do for the customer. As teams resist change, you must keep emotions in check and resist the urge to demonize people who reject your proposals. All too often, change efforts fail because change agents find themselves embattled in an “us versus them” conflict. It becomes a battle of wills rather than a collaboration to improve processes on behalf of customers.

As the person or group that is proposing the change, you have complete control over the discourse. How you respond to your detractors is an important indicator to everyone for how you plan to lead the effort. Demonstrating empathy and a desire to seek understanding can go a long way toward thawing tensions, and it’s a great way to model to others your new cultural values. These challenges can often be the most important opportunities for us to demonstrate what we want the new culture to look like. If you’re promoting a culture that highlights the need for employees to empathize, learn, and understand customer needs, it would be an ironic misstep if your change team wasn’t demonstrating that behavior when encountering employee concerns.

Many change efforts will find the most detractors within middle management. Depending on your organization, these are team leads that are leery to “rock the boat” or to make radical changes in how things are done. They can be considered the “frozen middle”; effectively, your senior leadership wants change, your employees want change, but the managers between those two groups resist.

This phenomenon is known as the middle-status conformity effect. Social scientists have long posited that this happens because the layer of middle management has the most to lose.

Middle managers can be insecure about sweeping changes in process because they finally have standing within their groups. In a sense, if you’re a lower-level employee and you make a mistake, you might fall from low to lower. If you’re a senior-level director, you have some distance from on-the-ground decision making. If you’re a middle manager, a mistake can be devastating. As a middle manager, there’s an intense pressure to prove to your directors and your reports that you have everything under control. Any misstep can be interpreted as an inability to lead. As sociologist George Homans observed, “Middle-status conservatism reflects the anxiety experienced by one who aspires to a social station but fears disenfranchisement.”14

Depending on the type of change you’re asking for, what might seem like a small change to you can seem like an incredibly risky change to a manager who is responsible for a team. In most cases, they’re the most exposed if the change doesn’t produce the desired results.

Therefore, it’s best to operate by making the charitable assumption whenever possible. Take time to empathize with your managers, leads, or any other detractors. Seek to understand their underlying concerns regardless of whether you believe they’re unfounded or misguided. Showing that you care about their concerns and that you’re not just going to dismiss them will go a long way toward building their trust.

Let’s be clear: working with people who oppose you is difficult. These battles can become volatile or even downright petty. Change is hard, and it can bring out the worst in us, especially when you’ve been successful doing things the old way.

In the book Rebels at Work: A Handbook for Leading Change from Within, authors Lois Kelly and Carmen Medina (whom we highlighted in Chapter 3) suggest that when you find yourself angry or frustrated, you must look at the other side:

Try to understand what it’s like to be the person (or group) you’re angry with. What are they trying to protect? What makes them uncomfortable? What are they afraid of? How people talk about something conveys more information than the words themselves. Listen for emotion beneath the words. This empathy will help neutralize your anger and help you see more clearly.15

Use Their Energy and Push for Positivity

Perhaps you’re in a situation in which you need to give constructive feedback to the person or group that is affecting the team’s ability to change to the new culture. Maybe it’s an employee who refuses to make time to talk with customers and creates friction any time the team wants to show customers early work to get feedback.

In those situations, it might require you to have a direct conversation with them and ask for the behavior to be corrected.

Microsoft has an online tool called Perspectives where employees can write about your performance and submit it to you and your manager for review. Amazon has its Anytime Feedback Tool with which employees can anonymously submit employee feedback.

Although, for the most part, these are great tools to help individuals understand how their behaviors affect those around them, this type of feedback isn’t always conducive to learning. Pointing out an employee’s lack of performance can be diminishing, especially if we don’t have a window into the complete picture. Dishing out negative criticism isn’t “just being honest”; it’s an ineffective way to encourage someone to change their behavior.

Studies show that giving people negative feedback on their performance doesn’t encourage them to reflect and change; often, it discourages learning.16 The challenge with feedback tools is that humans are not very good at rating other humans. Research shows that we fall victim to our own subjectivity, and it’s difficult for us to provide a stable definition of an abstract quality such as the effectiveness of a presentation or whether someone understands the business. Our rating is influenced by our personal biases and preferences. It can also be influenced by past experiences, our current standing within the organization, or our own personal goals. The bottom line is that the only thing that we’re truly qualified to give feedback on is how someone’s behavior affects our own personal feelings and experiences.

It turns out that focusing on our shortcomings is not the best way to encourage a culture of learning. In fact, studies show that when you give someone feedback on where they are failing, it ignites the “fight or flight” response, effectively shutting down their ability to listen and process what you’re telling them. In effect, receiving negative feedback impairs our ability to learn.

Think back to the last time someone told you that they were unhappy with something you did. Your pulse quickens and your mind fires as you try to come up with a reasonable explanation for your behavior.

Educators, particularly those of children, have known this for years. Positive reinforcement—focusing and pointing out behaviors that we want to see more of—is a far better mechanism for giving feedback than constantly pointing out where a student is failing.

Consider two different ways in which a teacher might give feedback to children in her class. First, using a method that focuses on the behavior that needs to be corrected:

“Jackie, you need to share with others.”

“Shari, your desk is a mess.”

“William, you need to do a better job during group time.”

Contrast that with focusing on the behavior that should be repeated:

“Jackie, I really like how you’re sharing with Molly.”

“Shari, thank you for putting your books in your desk before leaving for recess.”

“William, I like how you and Justin were working together during group time.”

Pointing out excellence rather than failure requires a mindset change, but it can be a powerful tool when encouraging behavior change.

Maximum learning happens when you focus on people’s competencies: when you start the conversation with what they’re doing right. You build trust, and you’ll find that people will be more receptive when pointing at ways that they can improve their performance even more.

If you’re considering leveling someone with negative feedback, take a moment to reflect on any positive behaviors that you can use and build on top of.

Redirecting Behavior

For example, let’s imagine that you’re working with a software team that’s exploring the problem space of families traveling on flights with children. It’s unclear what problems, if any, exist for these customers. The team is just getting started in looking for the best problems to solve to drive the biggest impact.

James, a software developer on the team, already has an idea for a mobile app and wants to start coding a prototype. The rest of the team is concerned that if James starts building an app, all of the resources will go toward that idea before they’ve even validated that a mobile app is the best solution for customers. He’s done this with past efforts, and the team has found themselves in the position of having a fully baked solution in search of a problem. They’re really concerned that they’re heading down a familiar path and are hoping that they can try a customer-driven approach by having discussions with customers—before they start to write code.

During team meetings, James insists that the mobile app is the best way to go and that the team is wasting valuable time by trying to validate the idea with customers. “I could build it faster than it would take for you all to validate if it’s the right idea or not,” he exclaims. “We should just release a limited version of the app and see how it goes.”

It can be tempting to push back on James’s desire to release a product without validating the need with customers first. We could point at previous projects for which he’s employed this strategy and it did not work. If we’re called in as mediators, it can be tempting to side with the team and put James in his place.

Although this might give us a short-term win with the rest of the team, it can prove problematic down the road when we need James to help us develop an idea that has been validated with customers.

In this case, it would be best to channel James’s energy to prototype. If we take a moment to reflect, we can empathize with him as he’s trying to apply his skillset (i.e., writing code) to help the team under a new customer-driven culture. It’s not that he’s unwilling to be customer driven, it’s that he wants to offer his best skills to the effort, rather than struggle trying to adopt new techniques for interviewing customers.

A better approach would be to tell James that we love his enthusiasm to prototype and point out how prototyping is an excellent way to get feedback from customers. We could advise against completely coding the prototype but encourage more lightweight exploration with customers, such as showing low-fidelity mockups or discussing benefits and limitations of the concept with customers. Rather than fight James on his desire to start prototyping, we’re actively choosing to take advantage of his energy and point it in a direction that can be less disruptive to the rest of the team. James will see that we value his contribution to the team and that we’re trying to align his skills in a way that can be helpful for where the team is currently at. It’s a redirection of his efforts to ensure that it still aligns with our goals of transitioning to a customer-driven organization. Instead of trying to generate new energy around our ideas, we consider James’s passion and determine the best way to make use of it.

This isn’t giving up your principles or plan, but it’s doing the hard work to find alignment between your goals and the goals of the people you’re trying to influence. Making that connection is the quickest way to gain their trust, and it further demonstrates the belonging cues of the customer-driven culture you’re trying to build—one that is built on learning, inclusivity, and psychological safety.

Make Change Digestible

On September 17, 2011, a group of two hundred protestors gathered in Zuccotti Park in New York’s Wall Street financial district. The gathering was organized by a pro-environment group and an anticonsumerist publication, Adbusters, that focused on economic equality, greed, and corruption, particularly in the financial services sector.

This protest was only a few short years after the US economy had fallen into the Great Recession. Protesters were frustrated as they watched the US government sign the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act (also referred to as the “bank bailout”). The bill made it possible for the government to spend $700 billion dollars of taxpayer money to purchase toxic assets from failing banks so they could ensure their continued operation.

During the recession, millions of Americans lost their jobs, their homes, and their businesses and still had not seen any economic relief. Many Americans were beginning to feel that the system was stacked against them, and tensions were high. The protestors claimed they represented the “99%,” reflecting the opinion that the wealthiest 1% of Americans benefitted the most under the current economy, leaving everyone else with nothing.

The organizers of the protest encouraged attendees to bring tents and supplies as the plan was to “occupy Wall Street” and completely disrupt the day-to-day business of the country’s top financial institutions. The idea was that protestors would live outside, in front of banks and other financial buildings, to show the world that they were in crisis. They wouldn’t leave until they saw some meaningful reform.

The movement gained the immediate attention of international press, and cameras soon showed several demonstrations taking place in the financial districts of other cities. Thousands of people poured into these areas, sitting and remaining immovable, holding signs and shouting at business professionals as they went into work. Nearly 60% of Americans supported the movement because they felt it perfectly captured their frustration with income inequality.17

Yet, two months after the movement began, the protestors in Zuccotti Park were forced to leave. Even though they tried to keep the movement alive by occupying banks, corporate headquarters, board meetings, and college campuses, the movement largely fizzled out as quickly as it began.

How could a movement that had widespread attention and support stop so abruptly?

One theory is that the change was indigestible to mainstream Americans. In a sense, protesters were asking for too much. To participate in the Occupy Wall Street movement, you needed to stop everything you were doing and either fly to New York or travel to your nearest financial district. Once there, you needed to commit to camp out for an undetermined amount of time. This was a tough proposition for many who were either busy looking for work or working multiple jobs to keep families afloat.

Types of Radicals

In his book Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World, Adam Grant suggests that change movements benefit from “tempered radicals.” These are individuals who find ways to get their ideas adopted among the mainstream. They ask for just enough to create meaningful change, but not too much that that they push willing parties away.

This is an incredibly difficult balance. You might find that within your own change effort, there’s a spectrum of radicalism. Some individuals find that change isn’t happening fast enough. They’re frustrated and don’t understand why others are dragging their feet. They propose radical ideas that push boundaries and shake up the status quo. On the opposite side of the spectrum, you have tempered radicals. They’re not interested in creating unnecessary tension and are highly allergic to change that will create backlash.

Essentially, each party is frustrated with the other because they feel they’re either asking for too much or too little. In some cases, each party will point to the other as the reason why change isn’t happening.

The reality is that you need both personalities in your change effort. Radicals help push the envelope. They keep the foot on the gas pedal, preventing the change team from becoming complacent or resting on past successes. Tempered radicals reel you in, helping you appreciate that “Rome wasn’t built in a day.” They tend to be far more pragmatic and are willing to meet people where they are. They seek to partner with their detractors and create common bonds that help their ideas go mainstream.

If you have these types of factions in your change movement, the trick is meeting both groups where they are and seeking compromise, letting them know you appreciate the passion or trepidation they bring to the effort. Engage both your radicals and your tempered radicals in meaningful debate, enlisting them both to help you find the proper balance for your change effort.

Additionally, you can utilize each personality when the context demands it. For your more difficult, nonconforming groups, it might be best to send in the tempered radical who will push for meaningful change but do it in a way that is more digestible to a skittish group.

For teams that are convinced of the new culture and are ready to get started, it’s best to send in your radicals. They’re already working with a group that’s converted, so they can push them beyond the boundaries of what they thought was possible.

In our journey in DevDiv, we had to appreciate that not all our software teams were in a place to immediately take advantage of our customer-driven approach. We had to meet each team where they were. Some were ready and able to radically change their working process; others needed more time and a measured approach. The key was having a change effort that supported both desires.

Consider your own customer-driven change effort:

Embrace Existing Tools

When promoting a change in culture, I’ve found that there can be a tendency to create distance from the “old way of doing things.” To that end, there can be a strong desire to introduce wide-sweeping systems or tools to encourage new behaviors. I’ve seen change agents tie their cultural ambitions to the rollout of a tool or software product. It’s not that these tools aren’t helpful—for example, Microsoft Dynamics is a comprehensive suite of tools that helps organizations all over the world organize their customer data and manage their relationships—however, these tools should not be a means to an end.

Depending on your resources, you might be ill-equipped to encourage culture change and engage in a massive software rollout. Therefore, you should consider your strategy wisely and look for smaller wins that can bring about more immediate change.

Working at a software company, there was a plethora of tools that we could’ve employed to gather and collect all the information that was being generated by our teams as they conducted customer interviews. In a sense, it was difficult to resist the urge to immediately jump to a software solution to use the data in even more complex ways. We’re a software engineering company; it’s hard not to look at everything as a software engineering problem. However, we quickly realized that software products can’t bring about meaningful cultural change. They can only augment it.

We believed that rolling out a massive, centralized database and expecting all our employees to engage in filling out forms and data entry for every conversation they were having was going to create too much friction. It was enough that we were asking them to engage in new behaviors (e.g., formulating hypotheses, creating discussion guides, talking with customers). To ask them to also add extra data-entry behaviors to their workday, especially when those behaviors would not be of immediate value to the employee, was a bridge too far.

However, we also didn’t want to lose all the organizational learning that was happening from every customer interview.

So we decided to be far more pragmatic. In DevDiv, we tend to be a pretty email-heavy culture. Email is widely used and adopted. For better or worse, email is our default communication tool.

Rather than try to implement something new and try to force everyone to use it, we decided to take advantage of what was already in place. We created an email alias called “CD Notes” (Customer Development Notes), and it was the de facto email address that all product teams used to share their notes from customer interviews.

Essentially, the ask was simple. When you’re sharing notes from your interviews, be sure to add CD Notes to the CC line. This was an extremely easy behavior for teams to adopt.

It also created a spot for anyone on the team to see the latest interviews and learnings. Our leadership team would periodically reply to emails with follow-up questions, suggestions, or further learnings. The minute employees saw that these emails were being read and commented on by leadership, investment in the behavior increased. Additionally, employees used search features already in Microsoft Outlook and Exchange to comb through previous emails and investigate past learnings. The email address became a past record of our customer learnings.

Was this the best solution? No. For instance, new employees couldn’t access emails from before they were hired. However, new employees created their own workarounds. For example, they would find an employee who had been with DevDiv longer and ask them to search their email for the things they were interested in. Not perfect, but acceptable.

And that is the key with a lot of this. Being pragmatic in the face of changing behavior is not letting perfect get in the way of good enough.

Microsoft Teams, which is a collaboration tool that uses chat, messaging, video conferencing, and document storage, is another tool that is becoming more widely used. We’ve leaned into that tool as well to encourage sharing information. For example, when conducting an interview with a customer remotely, the team will chat in real time, discussing the customer feedback and reacting to what it’s learning.

However, if a team wants to use Slack (a direct competitor to Microsoft Teams), we don’t push the issue. The team has already invested in the tool and has found a way to incorporate it into its day-to-day workflow. It would take too much time to uproot that behavior, and we’d spend more time trying to influence tool use over the more vital behavior: connecting with customers.

As you push for a change in behavior, consider how you might use lightweight tools that are already in use. Resist the urge to reduce cultural change to be about compliance with software or process adoption. This will prevent your team from becoming embroiled in unnecessary battles that miss the larger mission of creating less distance between product teams and their customers.

If you must introduce new tools, processes, or software products, try to implement them in ways that reduce the burden on employees. Gather feedback about the implementation and be willing to make concessions if it means that you’ll reduce unnecessary friction with teams. Consider testing new tools in smaller batches. Run a pilot with a small team and work out the kinks before rolling them out more broadly.

Meet Your Customers Where They Are

One final point. In this chapter, we’ve focused exclusively on how you should meet your fellow employees where they are regarding your culture change efforts. This requires us to find ways that make change more digestible to them. We’re consistently finding a balance of challenging them to change outdated behaviors but not pushing so hard that it causes backlash or revolt.

This same hack should be applied to your customers as well. Any change-management effort, whether you’re changing the culture of your organization or trying to change the way customers interact with your products, requires patience, reflection, and empathy.

It requires that we seek to understand where our customers are coming from, where their pain points are, and how the changes we introduce in our products affect them.

In Chapter 3, we talked about how when you’re applying the hack of “Building Bridges, Not Walls,” you’re effectively improving both sides of the glass. You’re improving the relationships and interactions of your product teams with one another so that you can improve the relationships and interactions of those teams with their customers.

If you’re rolling out a new pricing structure, deprecating a beloved feature for a better alternative, or pushing customers to a new ecosystem, it’s vitally important that you deliver the correct balance of change. You’ll discover this balance by engaging with your customers and having meaningful conversations with them. Uncovering their motivations and goals—the things they want to achieve with your products—will help guide you when you’re trying to shift your product offerings. When working with your customers in a consistent and continuous way, you’re always in step with them, so you have a deeper understanding of how changes in offerings will affect them.

Change can be difficult for your fellow employees, but make no mistake: it can be equally or more difficult for your customers. As you find successful ways to win over your detractors, make note of those strategies. These strategies can prove useful for influencing customers to change as well.

Applying the Hack

Here are some ideas that you can use to encourage learning over knowing in your teams and throughout your organization:

-

Spend quality time with the product team you’re trying to influence first. Attend their standups and, if possible, meet with their leadership team. Understand their values and business goals. By asking questions, listening, and observing behaviors, you can uncover their motivations and unmet needs. These can be applied when influencing them to change their process or engage more with customers. Interweaving their goals and the language they use to express those goals will show them that you’re invested and that you appreciate their unique needs.

-

Avoid solutions that are “one size fits all.” You need flexibility in your approach that allows others to feel like they own their own process.

-

Pick and choose your battles carefully. For example, if a team member wants to call a customer interview “an interview” and not “an experiment,” it’s probably best to let them have that win. The goal is to encourage terms that exemplify a language of learning. If employees are offering alternatives to the terms you’re suggesting, use it as a point of building, rather than tearing down. Although sharing the same language is vitally important, it shouldn’t be pursued dogmatically.

-

Actively work to eliminate your own hubris. Starting with a group by demanding change, holding on to dogmatic principles, or demonizing outdated behavior is the quickest way to be ignored. Avoid being the “company’s auditor,” as teams will be leery to work with you if they feel that you’re there to scold or correct their behavior.

-

Just as you want others to empathize with your customers, consider generating empathy for your teams. Avoid the fundamental attribution error. This is the bias that presumes a person’s behavior is a result of an internal factor (e.g., personality) rather than an external factor (e.g., environment). When a team is resisting change, don’t demonize them—actively seek to understand why. Even when someone appears to be difficult or obstructive, try to make the charitable assumption and understand that it may have nothing to do with you, your team, or your change effort.

-

Be open to new ideas or optimizations on your approach. Don’t put pressure on yourself to get everything “standardized” and “consistent.” Where appropriate, let teams have ownership over the process and allow them to make it their own.

-

Before preparing a request of another team member or division, ask yourself, “What could they use help with?” Offering help with their goals can demonstrate that you’re interested in developing a mutually beneficial relationship. Offering help, without immediately asking for something in return, goes a long way in developing long-term trust and support with others.

-

In meetings, rather than waiting for your turn to speak or present your part, be mindful of other discussions that are happening. Sometimes, we fall into a pattern of thinking to ourselves, “This conversation doesn’t apply to the work I’m doing, so I’m going to check my email” during meetings. When we do this, we miss an opportunity to ask ourselves how this conversation might apply to the work we’re doing. Learning about what others care about can be a powerful way to align our work to the goals of others on our team.

-

Rather than spend 100% of your time trying to convince the naysayers, consider spending your time supporting those who have joined you in changing the culture. Reflect on your investments using the “80/20” rule (also known as the Pareto Principle). Essentially, 20% of your activities should generate 80% of your results, not the other way around. If working with a team is going to be costly and is likely to produce little impact, consider walking away and returning at a later point.