Chapter 3. Build Bridges, Not Walls

When you closely examine the story of any breakthrough innovation, you’re likely to find that it was built on the accumulated knowledge from work that preceded it. Certainly, brilliant innovators deserve their rightful place in history. But we seem to always forget that their contributions to society were often nurtured within potent learning networks.

Another powerful hack we’ve come across in our cultural transformation is when groups are willing to share learnings across team and divisional boundaries. This might seem like an obvious idea, but we often don’t account for just how difficult it can be to share your expertise in highly competitive environments. In a sense, giving away what makes you special is viewed as a sure-fire way to make yourself obsolete. Every company wants cross-functional and highly collaborative teams, but tensions arise when people choose to focus only on work that will help them advance their own personal goals and professional aspirations.

Each time you watch a colleague get credit for an idea you inspired or a director get promoted for a successful team project, feelings of animosity or even contempt will naturally arise. Many of us are willing to collaborate so long as our original impact is clearly identified and acknowledged. However, that’s nearly impossible because collaboration is fast and messy. Ideas can be generated, discarded, and completely restructured all in a matter of a single discussion.

We should be fearless champions of our own work. After all, there’s no better person to explain the benefits of what you contribute to your organization than you. However, we must also acknowledge that credit-seeking and gatekeeping can be toxic and can have severe ramifications on the overall output of your team.

In this chapter, we explore how building bridges of knowledge and tearing down silos of expertise is a vital component of any cultural transformation. The sharing of knowledge, freely and openly, is foundational to a learning-first organization.

Giving Away Your Expertise

Building the very best software in an increasingly competitive world is challenging. We have software teams that find themselves in direct competition with one another all the time. It’s the nature of generating ideas and building on the work of others.

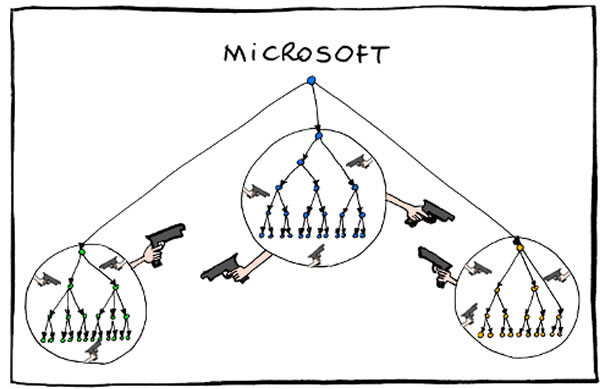

Some of you might remember the comical “org chart” that still circulates on the internet today, which you can see in Figure 3-1. It depicts Microsoft’s internal orgs in a standoff, guns drawn and pointing at one another.

Figure 3-1. Microsoft org chart from Manu Cornet’s “Org Charts” comic

Although my personal experience over the past six years suggests that we’ve made a lot of positive progress in this area, it wasn’t that long ago that Microsoft’s reputation was that of a company full of siloed “fiefdoms” and infighting.

When Satya sent the call for the company to strive for greater customer empathy and connection, our own research team had to come to grips with the fact that user research and customer development would be skills that were expected by many other disciplines at Microsoft.

Satya’s call was for all of us to be invested in learning from the customer, not just the user researchers.

In DevDiv, our product teams rose to the challenge with newfound enthusiasm and energy. They wanted to be empowered with the ability to do their own customer research. Product managers, engineers, and designers were asking for help with interviewing techniques and for feedback on their discussion guides. They were recruiting their own customers and building their own customer councils to help them shape product decisions. They were generating their own customer evidence and presenting findings that informed our leadership about emerging customer behaviors and consumer trends. One of the most challenging aspects about all of this was that they were getting good at it! To be honest, this was a bit of a scary proposition. It seemed as if our unique skills as user researchers were being “outsourced” to the rest of the company. Many of us had dedicated our careers and spent a lot of money on education to excel in the area of user research.

It would’ve seemed completely reasonable to dig in our heels—to put up walls—and immediately step in to gatekeep progress. We could’ve gone into our product team rooms like resident advisors conducting dorm-room searches: “OK everyone, put that hypothesis down! That needs an expert review before you test it with a customer!” We could have rung alarm bells and frightened our leadership into thinking our product teams weren’t ready to do the level of research that we were capable of. We could’ve focused all our attention on finding stories of teams doing research “wrong” and elevated these situations as examples of why the division needed us now more than ever.

Fortunately, Monty had a different vision for our team: one that positioned us as coaches, giving away our expertise to empower an army of product people to learn about our customers. This wasn’t a selfless or altruistic act. It was a matter of necessity. The train had left the station, and our teams were conducting Lean experimentation and customer development at an exponential rate. We could choose to step in front of that train and try to stop it, or we could hop on and help steer it in the proper direction. Additionally, we saw this as an incredible opportunity to help scale the efforts of a small research team. If everyone was investing in learning from our customers, our ability to raise the organization’s IQ about the customer and their needs was exponential.

Who Owns the Voice of the Customer?

As you pursue an organization that strives for zero distance between product makers and their customers, you might encounter pushback from disciplines that see themselves as responsible for collecting and reporting on customer insights. These experts, from user research, customer support, data science, marketing, quality control, product management, or design, might feel threatened, as if the work they do is being democratized.

The reality is that no one owns the voice of the customer except for the customer themselves. In a customer-driven organization, everyone must be responsible for connecting with customers and learning from them.

During the Mind the Product conference in San Francisco, Tricia Wang, a Fellow at the Berkman Center at Harvard University and cofounder of Sudden Compass, a consultancy that helps enterprises with customer development, discussed the role of user researchers in this emerging landscape where customer learning is becoming democratized. In her keynote address, she said:

In a cross-functional world, researchers move from being methodology gurus to discovery guides. Researchers don’t deliver the voice of the customer; researchers enable everyone to speak and to hear the voice of the customer. Your job is no longer the executioner of research, but about embedding yourself in the business as partners. To enable everyone to experience the customer and to facilitate that cross-functional conversation about that experience; to best impact product.1

As a research team, we came to the same conclusion. We found tremendous value in empowering our product teams to connect with and learn from customers. In fact, we were seeing that our organization valued our role as researchers even more, challenging us to find innovative ways to share our skills with all nonresearchers in DevDiv. Our role had evolved from being a small team that learned on behalf of the many to a team that would empower everyone to learn.

In the game of interoffice politics, having expert knowledge or desirable resources can be valuable. In unhealthy cultures, company experts can become gatekeepers, holding onto information or doling it out slowly to control the way the information is shared or evaluated. The motivations can be many, but often this need to control information stems from a desire to safeguard their role or function. The thinking goes, “They’ll never get rid of us, we’re the only ones who know how to…”

As your company transitions to a customer-obsessed culture, you might find those disciplines (UX, user research, design, customer support, marketing, data science, product management, etc.) begin to act as gatekeepers, trying to control the dissemination of skills and learning. It can be well intentioned and necessary; some might cite the dangers of letting employees talk directly with customers or suggest the harm that can come from sharing early ideas with customers.

It’s not that these concerns are without merit. Opening your business and regularly gathering information from customers, even with their consent, is a big responsibility that shouldn’t be taken lightly. When customers trust you with their data and their feedback, you’re entering an agreement to use that information in a responsible and secure way, and one that benefits them. However, the need to control the data that’s being collected, if left unchecked, can put more distance between product makers and their customers than is necessary. Taking a stance against learning and the free and open exchange of ideas is like taking a stance against the sun shining in the sky.

Sometimes, we must look at the bigger picture within our cultural transformation. Sharing knowledge, experience, and expertise is vital in getting an organization to change. For a customer-driven culture to take root, you must maintain that no single team completely owns the customer experience. It must be experienced together so that everyone can participate in the greater goal of delighting customers. Allowing others to adopt duties from your team, especially if you’re already responsible for connecting with customers, is a great way to apply your skills in new and more valuable ways. Industries will always require experts, but when you’re trying to move your organization to Lean experimentation and customer connection, these experts can get in the way of greater organizational learning and growth.

Consider how you, as a cultural change agent, can encourage others to share their knowledge. Create opportunities where cross-functional teams can learn from one another’s disciplines—sharing techniques, customer learnings, and new ways to frame problems.

Sharing Knowledge in DevDiv

It’s incredible when we bring a software engineer into our user research lab and allow them to talk directly with customers. At first, they might be nervous, especially when interviewing a customer in front of an “expert user researcher.” However, through our encouragement and guidance, we’re able to create a powerful moment of customer connection that far outweighs the impact of a 20-page report on customer findings. In those moments, the engineer, designer, or program manager makes a lasting connection with a person who uses their product. There’s a sense of ownership and responsibility that comes with that exchange. The customer no longer remains a nameless user or a set of ones and zeros stored in a database.

In fact, we welcome any member of the product team to participate in learning from the customer themselves. We don’t want to create distance between them and their customers.

Inspired by Cindy Alvarez’s book Lean Customer Development: Build Products Your Customer Will Buy, we believe people are primarily motivated by three things:2

-

They want to feel smart.

-

They want to help others.

-

They want to fix things.

Viewed through this lens, consider how your cultural changes and training are assisting each discipline to acquire new capabilities.

When we conduct our workshops, coaching employees in the art of customer development, we’re mindful that our materials don’t come off as if we’re the experts—loading the audience with technical jargon and pedantic domain knowledge, or making needling corrections to ensure people feel out of their depth and overwhelmed with all they need to learn to perform their own customer development. That would serve only to reinforce our expertise and (if I were being honest) might even make us feel superior.

It’s more important for our tools to be accessible, easy to get started with, and immediately useful.

No matter what your core area of expertise or professional discipline is, spend time looking over your own materials. Do they make people who are digesting them feel smart? Are they easy to use, and, do they give your employees enough knowledge to get started quickly? Or are they full of “do’s and don’ts,” creating a negative energy that zaps the fun out of creating customer connections? Are you enforcing policies that, when you observe them closely, are in place to protect only a single team’s expertise?

Build Great Products by Improving Both Sides of the Glass

There’s a powerful moment when a product team comes into our user research lab. They’ll sit on one side of the glass (the employee side) and observe the customer through a one-way mirror (the customer side). The customer is aware the team is on the other side of the glass, but not being able to see the team’s reaction helps them to focus on the tasks we’ve given them and lessen the feeling that they’re being “studied.”

What’s great about being a UX researcher is that I get to not only see the reactions from the customer, but from the product team as well. Essentially, there’s a moment being created on both sides of the glass. The customer gets to share their experience, and the product team gets a firsthand reaction to what they’ve built.

As you begin hacking your culture to be more customer driven, you’ll realize that your work requires improvement on both sides of the glass. Being customer driven is about improving the overall outcome for the customer. However, to achieve this, you must invest in building a highly functional and responsive team. As I reflect on my journey of transformation with DevDiv, I realize that we’ve not only created an environment that honors our customers, we’ve also created an environment that honors one another.

Therefore, having a great employee experience is essential to having a great customer experience.

Great EX (Employee Experience) = Great CX (Customer Experience)

If your team is having a terrible experience, chances are your customers are having a terrible experience, too. If your customers are unhappy, chances are your employees aren’t happy either. Creating a lasting culture that is deeply empathetic toward customer needs and experiences requires an organization that is deeply empathetic toward its employees’ needs and experiences. But here’s the good news: if you drive the teams toward being more empathetic with customers, there’s a good chance they’ll generate the skills required to be more empathetic with one another.

An interesting thing happens when I train teams in our Customer-Driven Workshop. As team members begin to talk to one another about their assumptions of the customer, they often uncover disagreements. For example, one team member thinks the feature should be targeted toward students, whereas another thinks they should be targeting faculty members. They collect some customer data and discover that neither students nor faculty members want the feature.

When each person realizes they were completely wrong, it is not only humbling, it can be a powerful moment of learning. It causes them to realize how easily their assumptions can be wrong. You can almost see them start to think, “What other things have I been making the wrong assumptions about?!” People have come up to me after our workshops and told me how being customer driven is a great strategy for situations outside of work. They often say that they may have been holding onto the wrong assumptions about family members, coworkers, and friends.

One gentleman, who had been in the software industry for some time, told me, “This workshop has given me a new way of looking at everything in my life. I need to slow down and not be so quick to assume everything. From now on, I’m just going to assume I don’t know anything.” I recall him talking about how he had been making assumptions about family members and reasons why they had drifted apart.

Although I find this sort of feedback gratifying and deeply powerful, I must be honest when I say that it has nothing to do with our workshops. Our job is to give them tools to connect with customers. That’s the point of the Customer-Driven Workshop.

However, connecting with others produces a powerful moment—particularly, when you connect with people whom you thought you understood but then soon realize you have more to learn about. Running customer interviews in our workshop can produce that effect for some of our product makers.

When they get on a call and talk to a customer from another part of the world other than Redmond, our customers become real; they’re not nameless, faceless users. In these moments, our workshop participants begin to realize that the customer profile they’ve been building in their heads was nothing like the people they met on the phone. That’s a huge revelation, and it can be sincerely humbling. It might even cause you to question other areas of your life where you’re making baseless assumptions.

That’s what we’re working toward in our workshops: to create that moment of realization for our team members, in a psychologically safe environment, so that they don’t feel embarrassed but are inspired by a newfound desire to challenge every assumption they have going forward.

Agents of Change: Carmen Medina

The US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) is responsible for collecting national security intelligence and identifying potential threats toward the United States. It’s a massive endeavor generating an infinite supply of global data, which requires constant collaboration and investigation.

In the late 1990s, the CIA’s ability to share knowledge and democratize data within the agency was woefully inadequate. In fact, most of the country’s national security information was being disseminated on paper; many believed that using electronic systems was a sure-fire way to put sensitive materials into the enemy’s hands.

Carmen Medina, a rising CIA analyst, had a proposal. Instead of printing reports on sheets of paper, intelligence agencies ought to begin publishing their findings instantaneously and transmitting them over Interlink, the intelligence community’s classified intranet network.3

The idea was immediately dismissed by her colleagues as unrealistic. Paper was a tried-and-true method, and the internet was an unknown entity at the time. They argued that with printed reports, you could ensure that the proper officials would receive them. If you put them online, there’s no telling who could access them. For the CIA, it was much more valuable to pool the information in controlled silos.

Frustrated but determined, Medina persisted. She kept bringing up the idea in meetings and advocated for the value of faster knowledge exchange. It seemed obvious that they should invest in an approach that ensured all their analysts got actionable data as quickly as possible. However, her colleagues became annoyed with her insistence. At one point, a senior-level coworker warned her, “Be careful what you’re saying in these groups. If you’re too honest, and say what you really think, it will ruin your career.”4

It nearly did.

Tensions mounted, and she was forced to look for another job within the agency. She took the only job available: a staff position that was well beneath her talents and ambitions.

After the attacks on the World Trade Center in 2001, the associate director of national intelligence was confronted with a hard realization. It was becoming increasingly clear that the culture of siloed information had allowed threat warnings leading up to the terrorist attack to go unnoticed. By 2005, the calls for change were becoming magnified, and many other officers within the CIA joined Medina in her quest to open the exchange of knowledge within the organization.

Because Medina had never really put the idea down, she started speaking up again, this time with a greater organizational awareness and credibility. Together, with the help of others, Medina created a “rebel alliance.” This group put forth a vision to have agents share intelligence, much like the popular online encyclopedia, Wikipedia. The idea was that the agency could post articles and other intelligence information so that other agents could comment on it or discuss it. The associate director gave the go-ahead, and a small server was installed to try it out. Through a grassroots effort, the alliance created Intellipedia, the agency’s first online knowledge network for spies.

Intellipedia is a rich and vibrant community, comprising equal parts message board, news articles, and wiki posts.

As of 2014, Intellipedia contained around 269,000 articles, 113,000 content pages, and 255,000 users.5 It has grown into a standard part of the intelligence community’s workday. It has a home page with featured and developing articles, help pages, and requests for collaboration. You can find tips on tradecraft in its pages and primers on conflicts in certain parts of the world.6 Essentially, it’s become a central hub where analysts get their daily information, search for previous reporting, and connect with one another.

Analysts agree that Intellipedia played an instrumental role in identifying terrorist threats during the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. It also proved useful in tracking Russia’s interference in the 2016 US presidential election.

Even though having a site with this many contributors is impressive, the website isn’t the cultural element we want to focus on—it’s the value of shifting to a culture that’s willing to share knowledge faster and more easily.

It shouldn’t take an international threat for your organization to embrace knowledge and continuous collaboration. So often, we seek to hold key information to ourselves, with a desire to maintain control or protect our teams or divisions. As the old saying goes, “knowledge is power,” and if we’re not careful, the knee-jerk response to withhold data twists itself into our culture like a noxious weed. Soon, you can’t even explain why you’re not sharing information with other workgroups; it just becomes the blanket reaction to any request for information. Although protecting customer privacy and trade secrets is incredibly important, I’ve found that many times, those legitimate interests can be “weaponized” and used as excuses for less collaboration.

The goal should be to protect sensitive data and create an environment of continuous and constant collaboration. There are many ways to anonymize customer data or provide only necessary portions of a product idea for a working group to move forward. Putting distance between the product team and its customers isn’t a sustainable path forward for your business.

There are important regulations in place, and we must abide by them to earn our customers’ trust. But we also must push ourselves to find appropriate and safe ways to learn and connect with our customers. For example, in our product Visual Studio, we have a feature that allows customers to give us feedback, directly from the product. Before collecting information about their issue, we ask the customer’s permission and ask if they’re willing to be contacted.

This allows us to aggregate these issues on the backend and present them to our product teams so that they can not only diagnose and fix the issues, but also get in contact with customers. These discussions can lead to even more feedback to improve the overall experience. Our customers love reporting issues this way because it keeps them in the context of their working environment. They also have a vested interest in improving the product they rely on every day, so many of them don’t mind being contacted for follow-up questions, especially if they’re getting help on an issue they reported. In exchange, we responsibly use their contact information and immediately remove it if the customer requests it.

I realize that this might not work under some extreme situations or regulatory constraints; however, you should still seek ways to create these types of customer and product team connections within the boundaries of what’s possible for your organization. Your default mode of operation should be to move in a direction that liberates knowledge, not a direction that confines it.

Pushing for Transparency

Employees cannot effectively serve their customers when they feel like they’re in the dark. Many organizations operate with little to no transparency, leaving employees with feelings of distrust between them and their organization. It’s almost as if the organization doesn’t believe that employees can be entrusted with sensitive business information.

That’s what many people said when Jack Stack, CEO of SRC Holdings Corporation, decided to move to a radically transparent culture.

In 1983, Jack was trying to save jobs at the fledgling engine manufacturing facility located in Springfield, Missouri. The economy was in decline, the company had 89 times more debt than equity, and it was looking certain it would send more than 100 employees to the unemployment line.

Together with 12 other managers, Jack raised $100,000 and purchased the company. What he did next was inconceivable: he handed it over to the employees.

From then on, he would enforce an “open book” policy by which all employees, regardless of rank or stature, could see the company’s complete financials.

He didn’t stop there.

He knew that his staff would need new skills to make use of the information, so he created training programs in which employees could learn how to interpret the company’s financial data. This created an environment of complete fiscal accountability. There was no way for his executive team to hide behind unearned salaries or lofty bonuses. Everyone was aware of how much money the company was making and how it chose to distribute it.

They were also aware of how much money it required to run the business. Employees started to appreciate cost-saving measures and often contributed innovative ideas to save costs and improve the business’ bottom line.

“They see the relation between operations and balance sheets,” Stack says. “If you teach people economic literacy, it doesn’t stop with the business. It goes into their house, and into their community.”7

Teams could see how each division created value for the company and what parts of the business needed the most help. Instead of shaming one another with financial performance metrics, employees leaned in to help one another. Stack proved that, when given the opportunity, employees would do the right thing with the information. This level of transparency and accountability heightened the willingness to share learnings because employees could see the interdependencies within the business.

Stack created an environment of trust that brought a deeper connection and meaning to employees’ work. It took an incredible amount of courage on his part to trust that his employees would use the information the appropriate way.

As of 2017, SRC Holdings has grown to 1,600 employees and booked $16 million in profits on $532 million in sales the previous year. It’s launched more than 60 companies in industries ranging from banking to medical devices to furniture.8

Admittedly, opening your financials to all your employees might be too big of an investment for your organization. Each organization has its own constraints, so there’s no one-size-fits-all suggestion here. However, we must acknowledge that when employees don’t have the proper information to do their jobs, it comes at a significant cost to the entire organization and, in some cases, it can dramatically affect employee morale.

Reflect on your teams’ willingness to share expertise and customer learnings. Perhaps there are ways you can give one another controlled access, to achieve the security you need, without the cost of blocking essential learning from happening. In difficult situations, seek compromise and common ground. The first priority should always be customer privacy, but the second priority should be organizational learning.

The Value of a Generalist

In any system of scale, it can be important to have clearly defined functions and rules of engagement. However, you’ll find that if these lines are too uncompromising, it can hinder innovation and critical thinking. Effectively, you end up in an organization so departmentalized and ruled by their job descriptions that you hear the dreaded phrase “that’s not my job” mentioned routinely.

Unfortunately, our customers don’t care at all about our organizational boundaries and hierarchy. They expect us to come together and create delightful experiences for them. If we choose to favor internal politics over our customers’ needs, they will simply take their business elsewhere.

That’s why we see major businesses being blindsided by scrappy newcomers all the time. These small startups aren’t weighed down with the same bureaucracy and permission-seeking of their competitors. This allows their employees to wear many different hats and provide a variety of functions.

In my work in DevDiv, I’ve had the opportunity to talk with lots of small businesses and startups. These might be teams of 5 to 10 people, building a smartphone app, providing consulting services, or building an online service. Many of these businesses are seeking funding and are driven by a courageous vision and persistent grit. In these teams, it’s not uncommon to find a shared sense of purpose and a radical diversification of duties. Backend developers will often take on frontend design work. The founder will also be the head of marketing and sales. The office manager will also handle payroll. Of course, this is mainly out of financial necessity. I’m sure if these startups had the financing to secure more head count, they would hire more specialized workers in a heartbeat.

As their companies grow, you’ll begin to see the rise of the specialist. The founder might bring on someone to head the company’s engineering or design efforts. They’ll eventually create a position for a director of marketing. Then, they’ll decide they need a team of dedicated UX researchers and designers. Little by little, the once small business becomes an organization defined by the various disciplines and divisions.

Then, innovation comes to a grinding halt. The business begins to falter by the weight of its own organizational chart. Political infighting and territorial safeguarding emerge as teams spend more time navigating interdivisional politics than on sharing knowledge or exploring the unmet needs of their customers. The role of manager becomes elevated as there’s an ever-increasing demand to manage resources and standardize work. As revenues rise, managers ask for more head count to keep up with the demands of the business. Soon, teams become bloated, and tensions rise as there are only a few projects that everyone seems to want to work on. The sales division begins to grow as the business takes on top-tier clients, and account managers develop deep relationships with their customers. Meanwhile, product makers become further and further separated from the customers who use their products.

Now, I don’t describe this growth pattern to demonize management or organizational hierarchy. There are more than 100,000 employees at Microsoft, and we could not function if we didn’t have an organizational structure that outlined each person’s responsibility. Being aware of your function within a large organization is critical to accountability. Having defined roles and clear job descriptions is necessary.

However, we must appreciate that the very systems we put in place to help us scale our business can also create distance between us and our customers. Anyone who’s ever called into customer support knows the sound of the automated operator rattling off various departments as you try to decide which of them can help you with your issue.

Innovative leaders understand this, and they’ll push employees to stretch the definition of their disciplines. They’ll bust the “that’s not my job” mentality that comes with an overreliance on specific job descriptions. They take advantage of each team member’s superpower and promote diverse points of view. They’ll encourage cross-functional collaboration to support a common goal rather than sabotaging an effort because it “wasn’t invented on our team.”

To do this, we must be comfortable with the value of being a generalist. So often, we wrap our identities around the work we do. In America, the most common question you are asked if you’re meeting someone for the first time is, “So, what do you do?”

Describing one’s job is a litmus test of self-worth and recognition of value. We often respond:

“I’m a developer.”

“I’m a researcher.”

“I’m a designer.”

These roles help us define what we do, but if we’re not careful, they box us in and become a limited set of who we are.

In DevDiv, we value the generalist, and we create enough flexibility for each person to stretch their expertise to meet the demands of the business.

My own personal story working in DevDiv is a prime example of this. When I was hired at Microsoft, I was listed on the org chart as a UX designer. However, throughout the years, I have been given permission to stretch the limits of what that entails well beyond what I thought was possible. I’ve had opportunities to train and mentor teams, design and coordinate large events, build an automated AI agent, write code and APIs, judge hackathons, host an awards show, produce and shoot short films, write books, and on and on.

Every day I’m confronted with a new opportunity and, most important, I have a leadership team that doesn’t hold me back, saying, “No, you’re a designer; you’re only responsible for producing red lines and UI layout.”

DevDiv has created an environment that utilizes each individual and allows them to contribute their talents and passions to the collective whole.

However, it took a small risk on my part. I had to buy into the idea that there was opportunity in stretching my job role—in taking on tasks that were well outside my job description. I could’ve leaned back and avoided projects that were not “something I was hired to do.” I could’ve said, “I don’t know how to do that, you’ll need to find someone else.” Thankfully, I listened to the messages from our leadership team to embrace a growth mindset. I told myself, “I don’t know how to do this yet.” Having this mindset allowed me to take risks and work on projects that were incredibly challenging but immensely rewarding. By taking a chance on projects that were not seen as “traditional software design work,” Microsoft was guiding me to some of the most meaningful and impactful design work of my career.

Cross-Pollinators

In his book The Ten Faces of Innovation, Tom Kelley, general manager of the legendary IDEO design and consulting firm, describes the value of the cross-pollinator. These are individuals who have eclectic interests and are considered “T-shaped” because, although they maintain a deep knowledge and expertise in one domain, it doesn’t prevent them from offering a diverse set of skills in other domains.

Kelley writes that cross-pollinators are:

[t]he project member who translates arcane technical jargon from the research lab into vivid insights everyone can understand. They’re the traveler who ranges far and wide for business and pleasure, returning to share not just what they saw but also what they learned. They’re the voracious reader devouring books, magazines, and online sources to keep themselves and the team abreast of popular trends and topics. Well rounded, they usually sport multiple interests that lend them the experience necessary to take an idea from one business challenge and apply it in a fresh context. They often write down their insights in order to increase the amount they can retain and pass on to others.9

As I said in the opening of this book, Monty and many other mentors and leaders at Microsoft helped me appreciate the role of cross-pollinator. I began to realize that I would be much more valuable to the company if I were willing to reject boxed-in descriptions of what I was hired to do. With their guidance and support, I was empowered to achieve more.

As a leader, consider how you’re taking advantage of the unique talents and passions of each of your team members:

-

Are you rigidly adhering to the scope of their job descriptions or are you encouraging them to stretch and cross-pollinate their diverse experiences?

-

Are you building walls around your discipline or are you creating bridges for teams to share learning and expertise?

-

Are you rewarding team members for bringing their own “personal brand” to their discipline or are you chastising them for “being distracted”?

If you’re not responsible for leading a team, reflect on how you can stretch the definition of your discipline. Consider investing in yourself by exploring additional skills that can be used by other parts of the business. The goal is to continue to “sharpen the saw,” building on a set of diverse skills that make you invaluable to your organization; for example:

-

If you’re a designer, what was the last book you read about business?

-

If you’re a program or product manager, have you ever considered taking a course on design? You might understand how to request design work, but have you had the experience of staring at a blank page and trying to bring a design idea to life? These can be transformational experiences that change the way you relate and empathize with members on your team.

Having exposure to other parts of your business can improve your ability to coexperience customer learning and share that learning in immeasurable ways. You’ll forge stronger relationships with your peers and establish strong bridges of mutual respect and understanding.

Finding Match Quality

In his book Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, author David Epstein writes about the notion of “match quality.” This is a term that economists use to describe the degree of fit between the work someone does and who they are.10 It’s a combination of their abilities and their passions. That’s the sweet spot.

As you consider roles and responsibilities in your organization (including your own), think about the flexibility that is given for employees to explore and define their own match quality. This doesn’t mean you should let everyone operate completely out of scope for what they’ve been hired to do, but it also doesn’t mean that you should strictly adhere to a prescriptive way of delivering each role in the organization.

To tackle difficult challenges, we must be willing to extend ourselves beyond what’s written in our job descriptions to a degree that is appropriate for the complex problems we’re trying to solve. Nebulous problems are not strictly confined to scoped, neatly-defined answers; therefore, neither should we.

As employees, if we’re willing to stretch ourselves beyond our roles and take on new challenges that require us to seek out new skills, we should be rewarded for those efforts.

During my time at Microsoft I have been rewarded, promoted, and given even more opportunities because I was willing to take the risk of finding match quality in my work.

Throughout the year, employees are asked to reflect on their performance by documenting their impact and the work they’ve done for the organization. The process is called Connect, and it’s a useful way for me to think about the work I’ve done and plan, with my manager (Monty), how I intend to grow and tackle new opportunities. This continued reflection and the subsequent conversations I have had with Monty are incredibly helpful. They allow us to align, to strategize, and to ensure that I am finding match quality in my work.

The simple reality is that as we learn, we grow, and what we care about and value changes over time. I’m grateful that as I began to take on challenges that I was passionate about, I wasn’t pushed out of the organization because these things weren’t part of my “day-to-day duties.” DevDiv saw value in what I was doing and encouraged me to continue the work even when I was feeling anxious that I had wandered too far out of scope for what the company hired me to do. As I waded into unfamiliar territory, I knew that my leadership team had my back, and that made all the difference. Being encouraged to learn and grow is a gift that any employer can give to their employees, yet so many often don’t. Some leaders throw away these opportunities in favor of short-term wins or results and wonder why they are suffering from high turnover on their teams.

“Make Microsoft work for you” is something I’ve heard Satya say on numerous occasions. I just love that, because it speaks exactly to my experience in DevDiv. I was passionate about connecting our product teams to the customers they serve, and I was driven by a strong belief that, if I was willing to share my expertise with my colleagues, it wouldn’t put me out of a job, but empower us all to drive empathy into the work we do.

Applying the Hack

Here are steps you can take to build bridges and tear down walls in your organization:

-

When providing new methods, templates, or tools, ensure that they can be adopted easily, and check in with employees to see whether they feel successful when using them. Just like your products, test your tools with your teams. Gather feedback and adjust them to make them easier to use. Look for ways to reduce steps and increase productivity. For example, the HPF reduces complexity by streamlining the hypothesis-writing processes down to filling out a set of parameters. This significantly reduces the cognitive burden of getting started with your first hypothesis.

-

Avoid “gotcha” moments in which you intentionally set teams up to learn a hard lesson. This sort of “shock therapy” rarely works, and it will cause unnecessary animosity because you’ve made employees feel ashamed, foolish, or stupid. Look to create moments that build confidence, not tear it down.

-

Seed learning into the culture by giving everyone an opportunity to learn something outside their expertise. For example, our Visual Studio Code team asks every employee on the team to program an extension for the tool, regardless of whether they know how to write code. This not only helps new members become familiar with the product, it also gives them the chance to reach out to their colleagues for help and gain confidence in building a new skill. These aren’t meaningless activities; they help employees feel connected to their customer, their product, and their workgroup.

-

Treat learning as a team sport. Encourage releasing learning early and often. Real-time reporting reduces waste and overproduction. If a team can benefit from what you’re working on now, show it to them—even if it’s incomplete. Don’t wait until you’ve got it perfect because many times you’ll miss your window.

-

Be inclusive. Look for different voices and perspectives. Make sure that teams have opportunities to coexperience learning from the customer and celebrate what they’re learning.

-

Actively seek partnerships with teams that are aligned with your customer-driven culture. Obsessing about the customer shouldn’t be a competition. It should be something for which everyone can find an important role to play. Avoid monopolies on methods, frameworks, roles, or other ways of working. You want a global mission with flexibility to add local optimization.

-

Look to diversify your specialists into generalists. When connecting with customers, encourage them to try methods that would often be seen outside their role or responsibility. Allow program managers, engineers, designers, or administrators the opportunity to formulate hypotheses, develop discussion guides, or conduct their own customer interviews to help them apply a holistic approach to product making.

-

If you’re leading a team, take time to learn your employees’ hobbies and interests. These passions can be a great way to generate motivations. If you have a team member who’s interested in painting, sculpting, making music, or baking, these are all “maker qualities” that can be channeled in a learning-first culture.

-

Create opportunities for members of your team to share their passions with the team. For example, during our weekly standup, we have open time for people to share anything they might want. It’s a great opportunity for team members to share ancillary interests. We’ve had discussions about drones, virtual reality, and graphic design. These aren’t necessarily topics that affect our direct day-to-day operations, but it’s a chance for a member on our team to share with us what they’re passionate about. It’s a great bonding experience, and we’re all better educated as a result. Taking time out of our busy schedules to engage in activities like this sends a strong cultural cue to our team. Learning from one another’s experiences is worth our time.

-

If you’re struggling to connect with another team member, consider taking them out to lunch. Changing the setting to a more personal one can often have the effect of getting them to “take their guard down” and have a more honest conversation.

-

Make time available to your team to learn about other roles in your company. Giving a designer the chance to write some code or allowing a product manager to attend a sales meeting isn’t a waste of time or a distraction. It’s a way for them to empathize with the other roles and responsibilities of the business. It also helps them understand the impact they have on other parts of the business.

-

Every time your teams are connecting with customers, it’s an opportunity to invite stakeholders to witness those interactions and join in the journey of learning themselves. Consider creating opportunities where project stakeholders can hear firsthand what their teams are learning from customers.

-

Ensure that the team not only collects information from customers together, but that it also analyzes the data together. For example: after a round of customer interviews, consider scheduling time for the entire team to get together in a room and review the interview notes. Each of them can mark parts of the interview that stood out to them (surprises, customer problems or frustrations, confirmations, etc.). Getting to discuss what you’re learning—as you’re learning it—can lead to meaningful conversations.