Coex! Coex! Coex!

I’ve been reading/studying/reveling in Finnegans Wake for 32 years now; I started it at 16. Joyce said in one of his joking moods, “This will keep the professors busy for the next thousand years,” and I believe him. I find new depths and profundities, and more jokes, every time I reread it.

For the historical record and as a politico-literary irony, it should be recorded that I was turned on to this great novel/symphony/jokebook/dream/myth/epic by James T. Farrell.

(Who? James T. Farrell was an influential and occasionally brilliant Marxist-realist of the 1930s and 1940s. His books became unfashionable when his politics became taboo. Farrell wasn’t as good as the liberal-Marxoid critics of the ’30s claimed, but he is good enough not to deserve the oblivion that has fallen upon him.)

Farrell had a defense of the Wake in one of his books of literary criticism. He said that Joyce’s epic investigation of the mind of one man asleep was not devoid of social significance and that it was a perversion of Marxism to dismiss such work as irrelevant to the Revolution. I don’t think Farrell convinced a single Marxist—most of them are still hostile to Joyce—but he convinced me. I bought the Wake on my 16th birthday, in 1948, started reading it, and haven’t stopped yet.

There are many good literary studies of Joyce, but the best introduction to Finnegans Wake is probably Dr. Stanislaus Grof’s Realms of the Human Unconscious, a study of the head spaces experienced under LSD. In particular, Grof’s term “coex systems” should be understood by everybody who writes about Joyce or tries to read him. A “coex system” is a condensed experience montage. E.g., you are reexperiencing the birth process, remembering prebirth interuterine events, reliving ancestral or archaeological crises of people/animals from whom you are descended, seeing the subatomic energy whorl from which Form appears, previsioning the Superhumanity of the future, and suffering horrible guilt over your unkindness to another child when you were four years old . . . all at once!

Critics have tried to explain Finnegans Wake by means of Freud and Jung, but Joyce was a quantum jump ahead of the psychology of his time. Everything in Finnegans Wake is a coex system in Grof’s sense. We can only understand it in terms of the latest findings in neurology, genetics, sociobiology, and exopsychology. To learn to read Finnegans Wake with ease and pleasure is to learn to think with your whole brain, “conscious” and “unconscious” circuits included, in holistic coex systems.

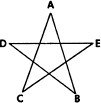

Dr. Nick Herbert devised Diagram A to illustrate a possible “context-dependent language” which could describe modern quantum theory.

In such a language A would take its total meaning from the context of B, C, D, and E; B, in turn, would take its total meaning from A, C, D, and E; and so forth. This is also the way an LSD-induced coex system operates, and the way the great dream-myth of Finnegans Wake operates.

Example: the word “thuartpeatrick” on page 1 of the Wake. With the simultaneity of a coex system, this contains the following.

1. “Thou art Peter,” the English version of the pun on which the Catholic Church is allegedly founded. (Petrus means rock, and Jesus’ pun goes on “and on this Rock I will build my church.”)

2. “Tu es Petrus,” the Latin vulgate of the same phrase, superimposed upon the English.

3. A pun on “thwart,” relating in the total context of the book to the sexual frustrations of the dreamer, H. C. Earwicker.

4. The “peat ricks” which used to stand beside every Irish home, providing fuel. This is one of a few dozen puns on the first page which help locate the dreamer in Ireland; others more specifically locate him in Dublin.

5. A pun on the Gaelic of “Patrick” (“Paidrig”), Ireland’s national saint, another reinforcement of the Irish locale of the dream.

6. A pun on “pea trick,” referring to the many other “pea” puns in the book, all revolving around the phrase “like as two peas in a pod” and referring to the fact that the dreamer’s sons are twins, physically indistinguishable but psychologically opposite.

7. In context, a reference to the repeated refrain “mind your p’s and q’s,” which refers to the dreamer’s guilts generally, and, by the association of the sound of p and “pea,” to “pee” and the dreamer’s unconscious urinary obsession.

8. A suggestion that the Catholic Church, or Finnegans Wake itself, or maybe literature generally, is a “pea trick,” or shell game, a semantic game in which words almost become the realities they symbolize.

This is not all there is in “thuartpeatrick,” I’m sure; it’s merely what I’ve gleaned in 30 or 40 readings of Finnegans Wake. Knowing Joyce’s methods, I wouldn’t be surprised if there are references to cannibalism in Lithuanian or to rivers in Russian also concealed in this word. (For instance, I was convinced for years that “the whiteboyce of Hoodie Head,” also on page 1, concealed only the White Boys, an Irish revolutionary group of the nineteenth century, and the Ku Klux Klan, an American parallel. Then I learned that Hode in German is testicles, and realized the phrase signified the spermatozoa in the testicles.)

Another delightful example of Joyce’s coex language is “goddinpotty,” from Chapter Four. Here we can find the following superimposed upon each other.

1. Garden party. The speaker in this scene is an Englishwoman and Joyce is parodying English upperclass speech, in which “garden party” indeed sounds like “goddinpotty.”

2. Garden party also suggests the Garden of Eden theme that runs all through the book (from the appearance of Eve and Adam in the first sentence) and, hence, the Fall of Man and, thus, in the same line of dream symbolism, the Fall of Finnegan from which the book takes its title.

3. The Fall of Man in the Garden of Eden links up with the dreamer’s guilt about some mysterious “sin” he committed in the bushes in Phoenix Park, Dublin.

4. “God” and “din” suggest the thunder god, Thor, who is one of the principal characters in the dream—possibly because the thunder strikes ten times during the night.

5. God-in-potty suggests, to anyone raised Catholic, the Host in the chalice, the bread that becomes the Body of God when the priest speaks the magic formula over it.

6. But the dreamer himself is the Host, in two senses: (a) in waking life, he is Host of an inn; (b) throughout the dream, he is periodically denounced, condemned, executed, and devoured cannibalistically, and rises from the dead. This repeats the pattern of the Christ myth, just as the blessing and eating of the Host in the Mass does. It also repeats all the other dead-and-resurrected vegetation gods in Jung’s collective unconscious. (In the Freudian personal unconscious, the trials and executions represent the dreamer’s sexual guilts.)

7. “Potty” again brings in the dreamer’s infantile urinary obsessions.

It will be observed that in analyzing only two phrases (three words) from the Wake, we have stumbled upon virtually every important theme of the dream, of the hero’s personal unconscious, and of humanity’s collective DNA archives. Joyce doesn’t pack quite that much into every phrase, of course; but if you have found only two levels of reference in one of his puns, you have probably missed at least two others, and maybe as many as in these examples.

Finnegans Wake is not just a great novel and a semantic symphony; it contains a whole science of psychoarchaeology and historical neurolinguistics. As John Gardner said of it, “Joyce dredged in that book. No other human being in the history of the world, including Beethoven, has ever given every single piece of emotion and thought and feeling the way Joyce did. He dredged up every ounce of his soul, every cell, every gene.”