CHAPTER EIGHT

The House as Path and Place

In the mid-1920s, Josef Frank found only scant success in realizing his many designs. Although he was able to build several sizable apartment blocks for the Socialist city government of Vienna in this period, he constructed only two houses of note, one for a client in Sweden (the Claëson House in Falsterbo in the far south of the country) and a double house at the 1927 Weissenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart. 1 And neither of these houses was particularly aspiring in terms of their spatial planning.

But in 1928, or possibly as early as the autumn of 1927, he at last received the commission he had long awaited—for a large villa.

The clients were Dr. Julius Beer, owner (with his brother Robert) of Berson Kautschuk GmbH, a maker of rubber soles for shoes, and his wife Margarethe, née Blitz. They were acquaintances of Frank and his wife Anna, and close friends of Hugo Bunzl, for whom, it will be recalled, Frank had designed the nursery school in Ortmann. 2

The site was a large lot in the Viennese suburb of Hietzing—originally three parcels of land, which Beer had purchased between 1923 and 1928. 3 Philipp Ginther, Frank’s assistant at the time, remembered that the house was first planned for another site (probably a property Beer owned in the district of Lainz in the south of the city), but that they transferred it to the new site after Beer was able to secure the third of the three lots. Construction of the house began not long thereafter. 4

The Beers were avid devotees of the city’s musical culture; they asked Frank and Wlach to design a house suitable for entertaining guests and business associates and for holding musical soirées. Frank, who was again responsible for the house’s design (Wlach, for his part, apparently undertook the task of installing the furniture and finishes), gave them several large, interconnected, and open living areas—splendidly suited for their needs.

From the outside, the villa closely resembles Loos’s Moller House, which was being completed around the time that work on Frank’s design began (fig. 132 ). They share the same basic cubic form: both have a projecting front oriel (though in the case of the Beer House it is supported on two thin pilotis), with the rear façades opening out onto extensive terraces and balconies (fig. 133 ). The fenestration of the Beer House, however, seems more adamantly random (partly as a result of its complex spatial plan, partly as a result of Frank’s penchant for deliberate disorder), and the depth of the house is shallower, a fact that is quite evident when it is viewed from the north side (fig. 134 ). Spatially, too, the houses are very different, and more importantly for our story, so are the paths (figs. 135 –43 ).

Figure 132 Josef Frank, Beer House, Vienna, 1928–30.

Figure 133 Beer House, view of the rear.

Figure 134 Beer House, view from the northeast. Arkitekturmuseet, Stockholm.

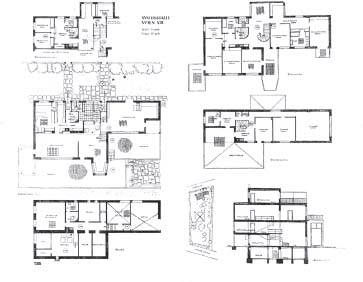

Figure 135 Beer House, plans, section, site plan. Moderne Bauformen 31 (1932).

Figure 136 Beer House, ground-floor plan. Moderne Bauformen 31 (1932).

Figure 137 Beer House, entresol. Moderne Bauformen 31 (1932).

Figure 138 Beer House, section. Moderne Bauformen 31 (1932).

Figure 139 Beer House, basement plan. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Garage; 2. Laundry; 3. Storage cellar; 4. WC; 5. Furnace room.

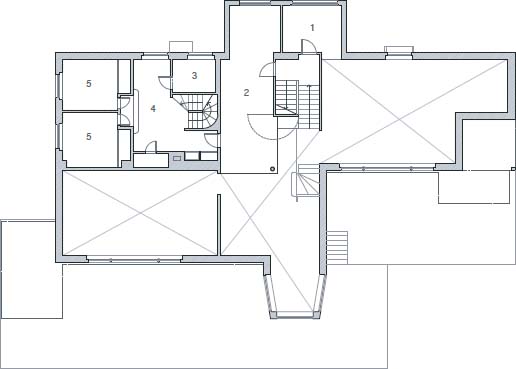

Figure 140 Beer House, ground-floor plan. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Vestibule; 2. Cloak room; 3. WC; 4. Service entry; 5. Butler’s pantry; 6. Kitchen; 7. Dining room; 8. Hall; 9. Living room.

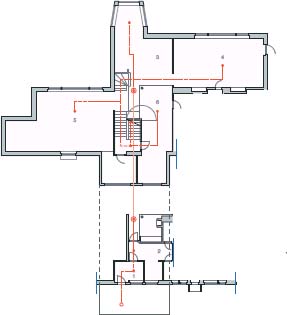

Figure 141 Beer House, entresol level plan. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Library; 2. Music salon; 3. Bathroom; 4. Anteroom; 5. Servant’s room.

Figure 142 Beer House, upper-floor plan. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Hall; 2. WC; 3. Bathroom; 4. Exercise room; 5. Bedroom; 6. Breakfast room; 7. Dressing room.

Figure 143 Beer House, attic plan. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Anteroom; 2. Dressing room; 3. Bathroom; 4. Terrace; 5. Bedroom.

Figure 144 Beer House, front façade from the side (detail).

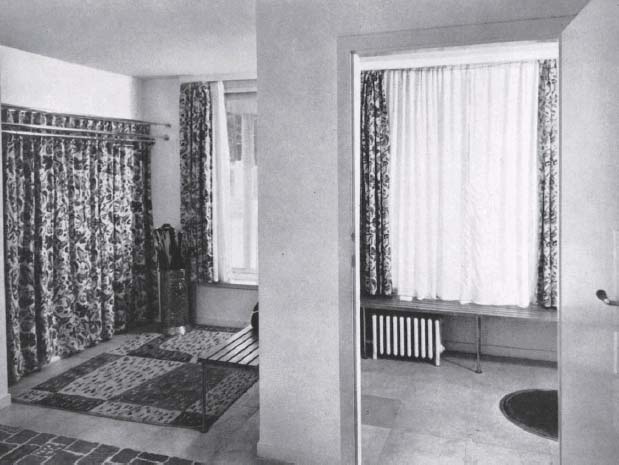

Figure 145 Beer House, vestibule and cloakroom. Innen-Dekoration 42 (1931).

The main entrance into the house—originally a brightly painted red lacquer door—is on the street side, under the oriel (fig. 144 ). (The door with the rounded-over surround to the right is the service entry and leads into the kitchen.) The route passes through a vestibule and cloakroom and then directly into the two-story hall (figs. 145 , 146 ). To the rear of the hall is a large, glassed-in alcove, and on the left is the main stair.

The impact upon entering this space, as the critic Wolfgang Born wrote at the time, was marked and immediate: “One enters the hall [from the anteroom] through an unobtrusive door and is at once standing, surprised and moved, in the heart of the structure. The first glance instantly offers a clear understanding of the entire arrangement.” This impression is enhanced by the impact of the open stair, Born continues, “which simultaneously reveals all of the levels of the house.” 5

Standing in the center of the hall, one can see on the one side into the double-height dining room and on the other to the stairs leading up to the living room (figs. 147 , 148 ). Looking back toward the entry and the front of the house, the continuation of the stair is visible, and just above it is the projecting entresol containing the music salon and other spaces (fig. 149 ). At this point, as Born noted, the whole lower spatial field can be observed. Frank’s concept for the house is also immediately apparent: from the music salon above, which had a Bösendorfer grand piano, music can be heard throughout the living areas, from the dining room up to the living room. It is a perfect arrangement for musical performance and enjoyment.

Figure 146 Beer House, view into the hall.

Figure 147 Beer House, dining room.

Figure 148 Beer House, view of the lower portion of the stair leading to the living room. MAK-Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst / Gegenwartskunst, Vienna.

Figure 149 Beer House, stair from the hall.

Figure 150 Beer House, view from the living room toward the hall. Innen-Dekoration 42 (1931).

What is also graspable a prima vista is Frank’s concept for the path. The stairs function as a means for joining the house’s spaces, but they also lead to stopping points along the way. The hall is the first of these stopping points; the living room, positioned about a meter and a half higher, is the second (fig. 150 ). Above is the third, the entresol, which contains the music salon and tearoom, as well as a library (the latter two rooms extend into the lower level of the oriel) (figs. 151 , 152 ). Beyond is the villa’s private sphere—two floors housing the bedrooms, an exercise room, and other spaces.

The elaborate progression was the result not only of Frank’s “musical program,” but it was also, as Born had hastened to point out, an attempt to make a visually and physically affecting experience. “The essence of this design,” he writes, “is the complete dissolution of all the usual spatial conventions of boxlike rooms, not only in the horizontal sense, in plan, but also in a vertical sense.” 6 Yet, at the same time, Born notes, the complex “interior spatial configuration… arises organically out of the circumstances of ‘living’”—as a direct response to the needs of its occupants. 7 The effect, he observed, was subtle but noticeable: movement through the house produced “a wonderful sense of relaxation… just as the inglenooks invite one to rest, the stairs induce one to climb. But how easy this upward movement is! New views, new surprises constantly present themselves, until one reaches one of the roof terraces (perfectly adapted for sunbathing), which provide the definitive fusion of interior and open-air spaces. Striding through [the house] provides one with an inexhaustible, resounding experience of space.” 8

Figure 151 Beer House, music salon. Innen-Dekoration 42 (1931).

Figure 152 Beer House, tearoom. Innen-Dekoration 42 (1931).

In 1931, a year after the house was completed, Frank published an essay he titled “Das Haus als Weg und Platz” (The House as Path and Place), in which he discussed the ideas that guided its design. 9 He had, he explains, conceived of the Beer House as a city in minia ture, with traffic patterns and designated areas for specific activities. “A well-ordered house,” he wrote, “should be laid out like a city, with streets and alleys that lead inevitably to places that are cut off from traffic, so that one can rest there.” 10 Frank emphasized that these paths should follow natural traffic routes, as in the cities of the past, not a simple grid.

In earlier times—especially in England, to which we owe the modern house form—such arrangements were traditional for cities and houses, but today this tradition has largely died out. The well-laid-out path through the house requires a sensitive understanding, and the architect cannot begin anew, which is why it would be important to revive this tradition. It is of the utmost importance that this path is not marked by some obvious means or decorative scheme, so that the visitor will never have the idea that he is being led around. A well-laid-out house is comparable to one of those beautiful old cities, in which even a stranger immediately knows his way around and can find the city hall and the market square without having to ask. 11

He insists that every aspect of the plan should contribute to this impression:

As an example of this, I would like to stress one very important element of the house plan: the staircase. It must be arranged in such a manner that when one approaches and begins to walk up to it one never has the feeling that he has to go back down the same way; one should always go further. If a house has more than two stories it is essential to consider what significance these stories have; if the third story is merely an attic, the flights of stairs should not be placed one above the other because that would awaken the feeling of an apartment block and one would never know when he had arrived. On the other hand, if this second level is a roof terrace, then it should be closely connected with the living areas, and the stairway should be separated as much as possible from the second-story bedrooms. Every twist of the stairway serves to heighten this feeling of continuous movement, not to save space. The largest living space, measured in square meters, is not always the most practicable, the shortest path is not always the most comfortable, and the straight stairway is not always the best—indeed hardly ever. 12

Frank’s language in the essay recalls Viennese urbanist Camillo Sitte’s influential text on city planning, Der Städtebau nach seinen künstlerischen Grundsätzen (City Planning According to Its Artistic Principles), first published in 1889. 13 In the book’s introduction, Sitte writes, for example, of “beautiful vistas” that “all parade before our musing eye, and we savor… the delights of those sublime and graceful things.” 14 Like Frank, Sitte must have been influenced by the same earlier theoretical discussions about space and subjective response; he was especially keen to consider how older cities—most of the examples he cites are in Italy—should be studied for the psychological lessons they might offer about our experiences of urban space. 15 He very soon emerged as a leading critic of regularity and uniformity in urban planning, and he became an oft-cited authority by those who rejected “straight streets” and urban regulation.

Sitte’s ideas were also very likely a key influence on Frank’s thinking. Whether he first read Sitte’s book at this time, reread it, or simply recalled it, Sitte’s concepts seemingly carry over into his design. Sitte repeatedly stresses the use of “organic” curving streets and irregularly shaped squares; Frank appears to have adapted Sitte’s ideas of the ideal cityscape for the domestic sphere, translating his urban ideas to a smaller, more intimate scale.

Yet there is another possible source for Frank’s ideas, one also very close to his interests: Leon Battista Alberti. In the fifth book of his De re aedificatoria (On the Art of Building), Alberti writes in a similar manner about spatial planning: “The atrium, salon, and so on should relate in the same way to the house as do the forum and public square to the city: they should not be hidden away in some tight and out-of-the way corner, but should be prominent, with easy access to other members. It is here the stairways and passageways begin, and here that visitors are greeted and made welcome.” 16

This could be a nearly faultless description of the paths in the Beer House (here, though, it must be said that Frank, unlike Sitte, for example, always thought of such experiences as individual ; he was seemingly unconcerned with the notion of collective or public experience, an outlook that Strnad and Loos also shared). But whatever the source for his notion of the relationship of city and house, Frank came increasingly to disregard the call of those architects of the time who wanted to rationalize the built world; he sought instead to create within the house natural, comfortable, and aesthetically pleasing spaces.

It was in the artist’s garret instead that Frank found his direct model. He writes:

The modern house is descended from the old bohemian studio in a mansard roof space. This attic story, condemned by the authorities and by modern architects alike as uninhabitable and unsanitary, which property speculators wrested with great effort from laws enacted to prevent its existence, which is the product of chance, contains that which we seek in vain in the planned and rationally furnished apartments below it: life, large rooms, large windows, multiple corners, angled walls, steps and height differences, columns and beams—in short, all the variety that we search for in the new house in order to counteract the dreary tedium of the regular four-cornered room. The entire struggle for the modern apartment and the modern house has at its core the goal of freeing people from their bourgeois prejudices and providing them with the possibility of a bohemian lifestyle. The prim and orderly home in both its old or new guise will become a nightmare in the future.

The task of the architect is to arrange all of these elements found in the garret into a house. 17

Frank’s own experience in his Wiedner Hauptstraße apartment no doubt had shaped his ideas about the garret and irregular spaces. Yet the plan of the Beer House is more than an assemblage of random or accidental elements. The entire space within is meticulously organized and segmented, with little left to chance. Among the principal divisions is a clear demarcation of the functional and living precincts. The kitchen, pantry, and housekeeper’s quarters are confined to a two-story section on the western corner, with their own entrance and stair (fig. 153 ). 18 They are joined, in turn, with the dining room, music salon, and upper-floor bedrooms by a series of discretely placed doors. The whole constituted thus a continuation and elaboration of the path.

Within the house itself are two further divisions, one between zones of movement and repose, and the other between the public and private spheres. Frank had previously employed walls or stairs to achieve a separation between spaces of transit and those of stasis. But in places in the Beer House this division is merely intimated so that the two merge formlessly. In the main entry sequence, for instance, the cloakroom is positioned to one side and framed by walls, providing an eddy in the circulation flow. As one enters the hall, a variety of possibilities opens up: one path leads to the rear alcove, another continues up the stairs to the living room and beyond. An additional path, subtly indicated, goes to the right, to the inglenook underneath the gallery of the music salon. Yet another route takes one to the dining room or out into the open area of the hall. Although each path is immediately evident, it is only casually “signed.”

These paths invariably terminate in casual sitting areas, the “piazzas” of the house—in German, Plätze —places or squares. They have a dual character: they are relaxed but they are also the products of precise manipulation. Paradoxically, the sense of comfort that pervades the house is the outcome of two seemingly opposite courses of action: a laissez-faire attitude and supreme control.

Figure 153 Beer House, service stair on the entresol level. MAK–Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst / Gegenwartskunst, Vienna.

Figure 154 Beer House, living room.

But control in Frank’s Beer House means something different than it does in Loos’s domestic Raumplan spaces. In decided contrast to Loos’s houses, the Beer House’s spaces are more open—both to the outside and to each other. There are large windows on the rear, and the visual field (for example, through the large window of the living room) extends outward—a condition, as we have seen, that is rare in Loosian villas (fig. 154 ). Frank also exploits windows—and the reflections they make—to foster a sense of spatial complexity and play. (Loos had done this early on in his designs using both windows and mirrors: the Kärntner Bar, the entry to the Looshaus, and the living room of the Scheu House come to mind here, though he mostly abandoned the idea later on.) Even more notable, however, is the relative openness of the Beer House’s interior. Standing at the door of the living room, just off the landing, one can look outward and see almost all of the downstairs living spaces; the music salon on the entresol; and, through a small aperture at the top of the stairs, the upper floor, where the stairs terminate (fig. 155 ). In contrast to Loos’s tactic of cloaking and revealing, Frank permits one to see—as Born described very well—nearly the whole of the Raumplan in action. The path extending up the main stair serves to normalize the experience of moving through what are in fact quite convoluted spaces, making the ascent—in actual fact, the entire experience—unhurried, gentle, and restful. In most Loosian villas of the 1920s, walking up and through the spaces is an activated and demanding experience; in Frank’s Beer House it is more of a leisurely amble, with many resting places along the way (fig. 156 ). Most of the paths are fixed and prescribed—hence the control. Frank also sought to determine the inhabitant’s pace: here and there he seems to want to invite her or him to slow down, persuading the subject to see, imagine, and feel. But the itinerary in the Beer House is less apparent than in Loos’s domestic works; it is not so much written in the architecture as it is sensed.

Figure 155 Beer House, view of the entresol and hall from the living room.

Figure 156 Beer House, continuous plan. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Vestibule; 2. Cloakroom; 3. Hall; 4. Dining room; 5. Living room; 6. Music room.

Here we come to one other principal difference between Loos and Frank in this period. It is articulated in formal terms, in the specific way in which their rooms are ordered. In short, Loos shows far greater rigor in this respect.

The American art historian Debra Schafter—and Czech art historian Lada Hubatová-Vacková after her—suggested that Loos’s tight spatial compositions owe something to the lessons in making ornament that he received in his early years while studying in Reichenberg (Liberec) and Brünn (Brno). Schafter writes that Loos, early in his career, had intuited “that the spatial and structural plans of architecture and applied art had gradually begun to absorb the principles worked out in ornament theory and practice.” 19 HubatováVacková extends this argument, suggesting that Loos took over the idea that spatial composition (Raumgestaltung ) and the making of ornament both had at their basis the same themes: “temporality, rhythm, movement, and corporeality.” For Loos, she writes, the Raumplan was “not the functional and economically efficient arrangement of accommodation that the modernists were arguing for. Instead, it seems to be a spatial rhythmizing of movement, an abstract transcription of deliberately intricate trajectories of motion. Instead of a ‘machine for living,’ Loos’s Raumplan was more a kind of kinaesthetic and optical play in manipulating space… the spatial image of the building’s interior is gradually transformed and is composed of the ensuing sequences of images by constantly walking through, descending and ascending and by the psychophysiological use of the space. The architect imposed this rhythmized choreography on the villa’s inhabitants. The interior’s main theme is virtual movement.” 20

Figure 157 Beer House, stair viewed from the entresol.

One could expand this line of thinking in another way: the plans of Loos’s villas themselves depict a sensibility informed by the logic of making ornament as it was developed in the later nineteenth century. The tight, spiraling forms of many of Loos’s houses—or, equally, his reasoned division of the cube into discrete parts—owe something to the sort of pattern-making that every architect of his generation absorbed as a student. If one examines Loos’s plans carefully, the “spatial rhythmizing of movement” that HubatováVacková describes becomes apparent not only in the movement sequences, but also in the manner in which the lines of his designs are laid down. Ofttimes, as Hubatová-Vacková notes, they are “picturesque,” infused with an older idea of poetry—though, one should add, they are always considered and ordered. 21

Frank, by contrast, though he demonstrates the same interest in the choreography of movement, usually opts for a much looser ordering. His “dance,” while also considered, is mostly liberated from the constraints of traditional patterning—often, it appears, deliberately so. Frank, in keeping with his aversion to systems and systematic planning, wanted to foster a stroll, one that was still largely predetermined but that did not follow the same sorts of strictures and restraints.

What Frank does share with Loos is his insistence on drawing a separation between the public and private domains. For Loos, this usually means shielding the private upper spaces through walls or abrupt turns in the stair. In the Beer House, Frank continues the openness of the space on the upper portion of the main stair. But he uses a subtle shift in its routing to indicate the transition (figs. 157 , 158 ). In “Das Haus als Weg und Platz,” he describes the thoughts behind each segment of the stair: “One enters the hall facing the stair. The stair, which turns outward into the room, presents its first step to the person entering. When he begins to climb upward, he can see up to the first landing and through a large opening into the most important room in the house, the living room. From this level, the stair leads straight up to two rooms, the study and salon, which are concealed from the living room but closely connected to it. At this point, the level housing the main living areas comes to an end. To emphasize this fact, the stairs leading up to the next floor containing the bedrooms wind in the other direction, and a clear division of the house is achieved.” 22 The partition of the stair resulted from an alteration of the traffic pattern, rather than by means of a physical barrier or an obvious sign. It arose, as Schmarsow had suggested, from experience, one that both informed and directly involved the occupant.

The design of the Beer House departed from Loos’s practices in one other important way: the Raumplan and path continue on its exterior. On the villa’s rear are stairs and terraces of varying heights that mimic the spatial play within (fig. 159 ). The process of strolling and resting carries on here; in the summer months, when the doors could be opened, the experience would have been unbroken, as one moved from the inside to the outside and back inside again. The terraces and balconies also represent a continuation of the path on the house’s different levels, each a terminus of its own. Although the possibilities for exterior movement are not as developed as they are, for example, in Frank’s Salzburg House project, they are still quite varied.

Figure 158 Beer House, upper-floor landing.

Figure 159 Beer House, view of the rear. Der Baumeister 29 (1931).

Frank, though, was not fully satisfied with the spatial solutions in the Beer House. By the middle of 1930, if not before, he had begun to rethink some of his basic design assumptions, in particular his allegiance to standard orthogonal planning. The shift is already apparent in “Das Haus als Weg und Platz,” which he probably wrote in the spring or early summer of 1931. He had intended his essay as a statement of his design aims for the villa. But partway through the process of writing he had, it seems, a change of heart, for contained within it are references to the idea that would come to define his architectural philosophy: his growing allegiance to nonorthogonality. “The regular four-cornered room,” he writes, “is the least suited to living; it is quite useful as a storage space for furniture, but not for anything else. I believe that a polygon drawn by chance, whether with right or acute angles, as a plan for a room is much more appropriate than a regular four-cornered one. Chance also helped in the case of the garret studio, which was always comfortable and impersonal. Practical necessities should never be an inducement to subvert formally a carefully planned layout because the viewer cannot understand its meaning, and, besides that, it is part of the architect’s art to bring form and content into a harmonious balance.” 23

After more than a decade and a half, Frank had at last returned to his earlier ideas about complexity and nonorthogonality. At the same time, he was intent that such designs should be natural and unforced. His statement about “practical necessities” not subverting a layout seems to be a swipe at the “functionalists.” Yet he also rejects Strnad’s ideas about using furniture to enhance the architectonic features of his houses.

Time and again, the regular four-cornered room misleads us into making architecture with furniture. One wants to use built-in elements, striking color schemes, and cubic forms to break up and articulate the banal space and to give it some character. The task of the architect, however, consists of creating spaces, not in arranging furniture or painting walls, which is a matter of good taste, something anyone can have. It is a well-known fact that in well-designed rooms it does not really matter what type of furnishings there are, provided that they are not so large that they become architectural elements. The personality of the inhabitant can be freely expressed. The space will emphasize those areas where every place and path should be. 24

Often forced to work in conventional four-cornered spaces when he and Wlach were called on to install interiors, Frank had been compelled to ameliorate the rigidity of the spaces with a free placement of furnishings. But he began to think at this time about alternatives in spatial planning, and illustrated in the article are three variant plans for a project for a house in Los Angeles.

It is described on the drawings only as the “Residence for Mr. M. S.,” without any further information. The only clue to its siting comes from the fact that in all of the designs the rear of the house (or portions of it) are somewhat higher than the front, meaning that it was intended for a gently sloping lot. Some of the drawings are dated—1930—meaning that Frank was probably working on the project while the Beer House was still being completed. The overall outlines of the three schemes are similar. They show a rambling, mostly one-story house arranged around one or more interior patios. In two of the schemes (which according to a note by the editors represent the second and third designs), Frank employed conventional orthogonal planning (figs. 160 , 161 ). He staggered and shifted the rooms, however, shaping a complex network of spaces, paths, sitting areas, and terminal points. To enhance the rambling effect of the plans, he also raised or lowered portions of the houses.

Figure 160 Josef Frank, project for a house for M. S., Los Angeles, 1930; second version; plan and section. Der Baumeister 29 (1931): plates 82–83.

Movement in these two house projects would have required repeated abrupt turns because in contrast to the Beer House the paths are often abbreviated. In point of fact, the movement sequences in both cases are highly condensed. The routes also are strictly determined; the relative freedom of movement in the Beer House—especially on the ground floor—is absent. In most cases, the rooms retain their separate identities, and passage from one room to the next occurs at the thresholds, which are sometimes displaced—“slipped” off any apparent axes. It is as if Frank had laid out the individual rooms on a mostly horizontal plane and then slid or shuffled them around, altering their positions relative to each other.

What is also fundamentally new is the way in which he inserted open spaces—small courtyards and patios—into the plans. He had experimented with this idea before—for instance, in the houses for Vienna XIII and H. R. S. in Pasadena—but on a far more limited basis. The two orthogonal versions of the House for M. S. have numerous such insertions, and they form an essential organizing scheme. Groups of rooms—mostly those with the same functions (entry, living, dining, service, bedrooms, and so on)—are arranged around these “openings.” This device serves to divide the plans in a logical and practical way. But because there are also large numbers of windows looking into each patio or courtyard, these insertions serve to add complex lighting effects. In places where there are first walls and then openings, the lighting effects are punctuated, as are the views.

Figure 161 Los Angeles project, third version, plan and elevation. Der Baumeister 29 (1931): plates 82–83.

The paths in the second and third schemes function in similar ways. They require multiple right-angled turns as one weaves one’s way into and through the interiors. Along the paths are numerous stopping points, in inglenooks or other sitting areas. The overall effect, though, is a meandering path through what one might describe as a warren of rooms. The complexity arises in large measure not from the shifts in level or from the differing heights of the rooms but from the circumstance that nearly every axis is quickly interrupted, as are any direct sightlines. Walking through the spaces would have produced a layered sequence of experiences and impressions—richer perhaps even than those of the Beer House. Absent, on the other hand, is the latter’s clarity and legibility. The paths in the two projects might have seemed, as Frank hoped, like a stroll through an old city, but one whose plan was not as immediately comprehensible to the visitor.

The first of Frank’s three schemes for the House for M. S., however, departed considerably from the other two schemes–and from his previous residential designs (fig. 162 ). Although the outer footprint is similar to the other two M. S. designs, Frank abandoned right-angled planning, introducing instead curvilinear and oblique lines that produced a series of irregular spaces.

Figure 162 Los Angeles project, first version, plan and elevation. Der Baumeister 29 (1931): plates 82–83.

The mostly one-story house is in the form of a U, with the open side facing the rear. At its center is a serpentine patio arranged around a long “pool.” The main body of the house is divided into three functional zones: a service area on the northwest corner (with servants’ quarters below); the living spaces—dining room, tearoom, and living room—on the northeast; and a bedroom wing, which takes up the entire south side. The bedroom wing is slightly raised, about a meter and a half, so that it rests slightly above the patio on that side.

The path commences at a four-columned portico, leading first into a small porch, then into a larger vestibule. Upon entering this space, one would have seen an open cloak area to the right. A ninety-degree turn brings one into the elongated hall, the first of the house’s nonorthogonal spaces. Directly beyond is the living room; to the left are the dining area and tearoom. Framing the dining space is a long, arcing screen. The screen, whose form is echoed by the outer wall of the tearoom, in turn is divided into separate movable panels, permitting the room to be configured in a number of ways. The dining room, thus, could have been made nearly fully enclosed, almost entirely open, or something in between. By making the panels adjustable, Frank envisioned an active plan, which would have also allowed for variations in the path. He repeated the same idea at the intersection of the dining and living areas, positioning there a straight sliding door of similar construction, which would have also multiplied the spatial and movement possibilities. Long, continuous windows situated along the outer wall of the tearoom / dining room and the inner walls—facing the patio—of the tearoom / dining room and living room would have made for manifold and affective lighting and viewing effects. In combination with the irregular and bending edges of the spaces, Frank sought to weave a highly variegated set of architectonic experiences.

The complexity of this main path is reiterated in the bedroom wing. The path begins in the hall and continues up a short, slightly bending flight of stairs. After another sudden turn—now to the left—one would enter the inner hall. It, too, follows the outline of the serpentine patio along the inside. Along the outer edge, the space is angled. This has the effect of making two of the bedrooms nonorthogonal; the other three are roughly L-shaped polygons. Only two of the bathrooms are conventional rectangular rooms. (The third has one curving wall.)

Frank no doubt intended for the paths in the M. S. House to serve as instruments for accentuating its eccentric spatial ordering. Their routing would have forced an observer into direct confrontation with the unconventional spaces; moving along the succession of features and effects would have underscored each special moment. It is difficult—from the simple lines on paper that we have—to predict precisely how the scheme would have operated in this way, but all of the evidence points to a house that would have been oddly comfortable and nonetheless a little jarring—exactly, it seems, what Frank was aiming for.

He would continue to mine these ideas for the next quarter-century.