CHAPTER SEVEN

The Punctuated Path

In 1924, a little more than a year after Loos had put the last touches on the Rufer House, he decided to leave Vienna and move to Paris. His reasons had to do in part with his displeasure over the decision of the Socialist municipal authorities in Vienna to shift the emphasis of the city housing program from low-density row house settlements to high-density urban apartment blocks. Loos had headed up the housing office for several years after the war, and he was truly troubled by the idea. He had long advocated an approach that gave more freedom to the “settlers”—the city’s legions of homeless or under-housed—to determine the form of their own dwellings. But he had also grown weary of the criticism he faced in Vienna, and he was irritated and resentful that grand public commissions were still not forthcoming. He wanted the chance to build important works.

In Paris, though, he found only modest success. He was lionized for his early writings and hailed for anti-ornament views, yet precious few opportunities to build came his way. 1 He completed only a single Raumplan house there, in 1926, for the Dadaist writer and poet Tristan Tzara. 2 But the next significant advance in his thinking about the affective path appeared in an entirely different project, a villa in Vienna, which he designed while still living in France.

Work on the Villa Moller, on Starkfriedgasse near the northwestern edge of the city, began in 1926 and was completed the following year. Loos made several trips back to Austria to supervise its design and construction. The client was Hans Moller, owner of a cotton mill near Náchod in what is now the Czech Republic, and his wife Anny. They were a progressive, cultured couple: Anny had studied art at the Bauhaus, and among their intimate circle of friends were Karl Kraus and Arnold Schönberg—which is doubtless how they had come to make Loos’s acquaintance.

Loos gave them one of his most complete Raumplan houses, an exuberant tour de force of his spatial planning ideas. 3 But far more than that, he was able to reimagine the ways in which a dwelling might compel new perceptive and somatic sensations. For the Moller House marked the beginning of a new chapter for Loos: up to this juncture in his career the affective path had been a mostly contained and discrete portion of his planning strategies. Now he made it a far more integral constituent.

From a distance, the Villa Moller appears at once deceptively simple and strangely discordant (fig. 104 ). The structure is again in the form of a cube, with a large projecting front oriel. Its street-side façade, like almost all of Loos’s urban dwellings, is nearly blank, a mask to shield its inner domain. But the rear side is more open, with broad terraces giving out onto a capacious garden—once more, a typically Loosian gesture, which he thought apposite for what was the private face of the house (fig. 105 ).

Figure 104 Adolf Loos, Villa Moller, Vienna, 1926–27. Photo by Martin Gerlach Jr. Bildarchiv der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, Vienna.

Figure 105 Villa Moller, rear. Photo by Bruno Reiffenstein. Bildarchiv der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, Vienna.

Figure 106 Villa Moller, entry.

The entry sequence resembles in some ways that of the Rufer House, tracing a line from a central opening along the front edge and the sidewall. There are, though, dissimilarities that are telling and of consequence. The main door is at the center of the house’s street-side façade, under the oriel (fig. 106 ). Beyond is a narrow anteroom, lit by a clerestory window and a three-tiered lamp (fig. 107 ). To the right, the path continues up a short flight of steps; then, where it reaches the sidewall, it turns abruptly ninety degrees to the left (fig. 108 ). And, just as one reaches the top of this first flight of stairs, one is compelled to turn again, this time a full 180 degrees. Here, for the first time, the upstairs spaces erupt into view (fig. 109 ). From this vantage, it is possible to see up and through the house because Loos sliced through the walls in several places, devising several thin sight corridors.

Figure 107 Villa Moller, clerestory window and light fixture in the vestibule.

Figure 108 Villa Moller, view from the vestibule to the first stair.

Figure 109 Villa Moller, stair.

Although the Raumplan in the Moller House is abundantly developed, it is these apertures that form the essential innovation in its design (figs. 110 –13 ). Loos’s previous houses had all essentially relied on either open staircases or fully enclosed ones. As one climbed from level to level, one could either take in the spatial spectacle fully, or it was shielded, with the spaces to be revealed only at the end. What Loos achieved with the “partial” walls of the Moller House was something quite apart: a dotted or, better, punctuated, viewing experience. The vistas open and close with each change in the viewer’s position, and, because at certain moments or positions for the observer two or more of the apertures align, the prospect might be extended, only to be foreshortened or obstructed altogether again as one moves along (fig. 114 ). To walk up the stair, thus, is to be confronted with a series of clipped impressions, the views mixing seamlessly with the details of the house itself.

Figure 110 Villa Moller, ground-floor plan, 1:200. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Vestibule; 2. Cloakroom; 3. Maid’s room; 4. Laundry; 5. Garage; 6. Kitchen; 7. Storage; 8. Housekeeper’s room; 9. Pantry.

Figure 111 Villa Moller, first-floor plan, 1:200. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Hall; 2. Upper portion of the hall; 3. Study; 4. Music salon; 5.Terrace; 6. Dining room; 7. Kitchen.

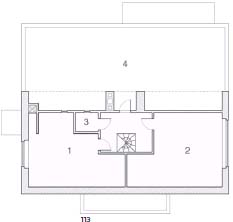

Figure 112 Villa Moller, second-floor plan, 1:200. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Room; 2. Bath; 3. Room; 4. Bedroom; 5. Terrace.

Figure 113 Villa Moller, top-floor plan. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Guest room; 2. Atelier; 3. WC; Roof terrace.

Figure 114 Villa Moller, view of raised seating area and stairs.

Figure 115 Villa Moller, isometric drawing of the main path. Grafische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, ALA 912. Copyright Kulka Estate, reproduced with permission of Mara Bing and the Kulka Estate, New Zealand.

Figure 116 Villa Moller, sections. Grafische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, ALA 909.

Figure 117 Villa Moller, view of the hall

Loos achieved in this way the full dynamic realization of Strnad’s idea of serial disruptions and distortions. As the subject moves upward a vista is opened, and where a partial wall intervenes, it is blocked again. The result is a layered sequence. Or, to express it another way: at the very moment one begins to take in the spatial ordering there is a fluctuation of the display, and one is made to re-form or recalibrate her or his mental image. The rerouting of the Moller House’s stair—the upper portion of the entry stair jogs sharply to the right—serves to reinforce this sense of constant realignment by introducing a somatic element—and, where one might touch the house’s surfaces (the railings, walls, and stairs), also a haptic one. The experience of moving, looking, and touching, along with the attendant rapid changes in sensations, fosters a complete and powerful architectural engagement—even before one reaches the hall.

Loos was especially attentive to the routing of this sequence, even going so far as to have it drawn in detail as an isometric projection (fig. 115 ). His reason for doing this is abundantly apparent if one examines the sections, which reveal little about how the stair functions (fig. 116 ). It is, indeed, almost impossible to take in completely how the sequence works without the isometric view. Even while one is walking along the route for the first time, it is hard to comprehend fully. It is only after making the final turn at the top of the last flight of stairs and the hall at last becomes wholly visible that the path is completely understandable (fig. 117 ).

Figure 118 Villa Moller, view from the dining room to the music salon. Photo by Martin Gerlach Jr., ca. 1930. Grafische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, ALA 3194.

On this main floor is a splendid instance of Loos’s spatial economy, with each zone accorded the height it requires. The hall is divided into lower and upper seating areas. The raised portion has a lower ceiling and is effectively an inglenook, intended for more intimate social interaction—for close and relaxed conversation—while the front space (on the main floor level) establishes a stopping point—a brief “eddy” along the path—and is higher and more open, suggesting only a quick and momentary stop before one should move on.

Along one side of the main floor, facing the rear terrace, is another important destination: the music salon. Roughly a meter higher, the dining room is also positioned along the rear wall of the house. Loos had originally drawn a nearly full physical separation between the rooms (figs. 118 , 119 ). The very narrow stair that he originally placed at the edges of the two rooms was not easy to climb, a problem that later residents remedied by converting the entire edge between the rooms into a stair (fig. 120 ). Loos, so it appears, was more concerned with the visual interaction between the two rooms than with generating a practicable way of moving back and forth from one to the other. He seems to have wanted those visiting to stroll back into the hall, and then up the short stair there before entering the dining room. The path thus functioned one way, the view possibilities another—a situation that is quite evident in the path plan (fig. 121 ).

Figure 119 Villa Moller, view from the music salon to the dining room. Photo by Martin Gerlach Jr., ca. 1930. Grafische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, ALA 3191.

Figure 120 Villa Moller, view of the dining room.

Figure 121 Villa Moller, con tinuous plan. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Entry; 2. Cloakroom; 3. Hall; 4. Upper hall; 5. Music salon; 6. Dining room.

Loos’s strategy of opening and closing views (and, also, the physical connections between spaces) is facilitated further through the use of doors in some of the spaces. From the edge of the dining room, for example, it is possible to look up the stair to the upper-floor bedrooms (and to the outside through the window) (fig. 122 ). Someone seated in the dining room can also glimpse the hall through the stair. Another sliding door in the music room enlarges the view; from several positions in the dining room, it is possible to see both sets of stairs in the hall (fig. 123 ). Closing one or both of the doors conceals these views. Pocket doors between the dining and music rooms permit the view to be foreshortened even more and thereby make the dining experience more intimate. Here, as ever, Loos also showed particular concern with the haptic qualities of the hardware (fig. 124 ). If one begins to move, all of the views come into play again. They become manifold and swiftly changing. Along the route that leads upstairs to the bedrooms, for instance, almost the entire spatial field is disclosed, including the entirety of the hall, the end of the stair from the lower story, and the stair to the library (fig. 125 ). After slowly, progressively laying bare the various segments of the Raumplan along the entry path, Loos provides a nearly full résumé of it.

Figure 122 Villa Moller, view of the stair from the dining room.

Figure 123 Villa Moller, view of both stairs from the dining room.

Figure 124 Villa Moller, detail of the pocket door between the dining and music rooms.

Figure 125 Villa Moller, view of the hall from the stair.

Figure 126 Adolf Loos, project for a house for Josephine Baker, Paris, 1927; model. Photo by Martin Gerlach Jr., ca. 1930. Grafische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, ALA 3145. Copyright Kulka Estate, reproduced with permission of Mara Bing and the Kulka Estate, New Zealand.

Figure 127 Project for a house for Josephine Baker, plans 1:100. Drawing by Heinrich Kulka. Grafische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, ALA 588. Copyright Kulka Estate, reproduced with permission of Mara Bing and the Kulka Estate, New Zealand.

The concept of a punctuated path appears again in another of Loos’s designs of this period, his unrealized house for the dancer, singer, and social activist Josephine Baker. Loos worked on the design in 1927. 4 He seems to have met Baker several years before, but quite uncertain is whether she actually commissioned him to design the house or whether he undertook the project on his own volition. (The latter, given the evidence we now have, seems more likely.) The intended site, as it is shown on some of the drawings, was in Paris, on a corner of the Avenue Bugeaud, in the sixteenth arrondissement. All that now survives of the project are a model and a few plans—documents that raise more questions about Loos’s intentions than they can answer (figs. 126 , 127 ).

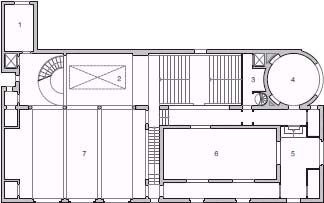

Figure 128 Project for a house for Josephine Baker, ground-floor plan. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Entrance; 2. Office; 3. Kitchen; 4. Servant’s room; 5. Garage; 6. Changing rooms.

Figure 129 Project for a house for Josephine Baker, first-floor plan. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Wardrobe; 2. Hall; 3. Office; 4. Café; 5. Petit salon; 6. Swimming pool (underwater portion); 7. Grand salon.

Figure 130 Project for a house for Josephine Baker, second-floor plan. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Void and skylight above; 2. Salle à manger (dining room); 3. Swimming hall and ambulatory; 4. Swimming pool (water level, with skylight above); 5. Bedroom; 6. Bathroom.

The fragmentary nature of what is left to us in the Loos archive and the dearth of other records has occasioned a great deal of speculation about the house. Largely passed over, however, has been the rather singular nature of the entry sequence (figs. 128 –30 ). Its routing was a one-off for Loos: it was surely an experiment and, as it would turn out, one he would not repeat.

The first anomaly appears at the very outset: the double-door main entry leads to a grand stair that extends straight up to the main floor. It is broad—exceptionally broad for Loos—and absent are the twists and turns so central to his other Raumplan houses. The ceiling is also partially open to the second floor, which would have made this space unusually light and airy for one of Loos’s domestic entries.

On the second floor, the stair leads directly into the hall—still along the same axis. Only here is one required to turn, slightly to the right, to reach the stair to the third floor—or ninety degrees to the left, to continue into the grand salon. Almost everything to this point is curiously conventional—hardly Loosian at all—except for the opening in the ceiling, which is illuminated by a skylight above and allows a glimpse into Baker’s private sphere and the grand salle à manger —the dining space—on the next floor. But it is only when one continues beyond—to the indoor swimming pool adjacent to the salon—that elements of a Raumplan finally come into play. At this point, there is an extended ambulatory that surrounds the pool on all four sides: it is raised along one side; it is at the same height as the salon on two sides; along the fourth is a second stair from the ground floor, extending up from a side entrance. But the pool is not accessible from this part of the house, for its surface is up on the next floor. Instead, placed along this ambulatory are four windows, permitting an observer to peer inside into the water.

There has, in particular, been much speculation about the meaning of these windows. Some years ago, Farès El-Dahdah suggested that Loos had contrived the whole house as a voyeuristic scheme, the windows in the pool especially to gaze upon “an aquatic world in which the naked body of Josephine might dive at any moment…. The window becomes a tableau of Loos’s own desires.” 5 More recently, Anne Anlin Cheng made a similar argument: “[T]he inhabitant of the house (that is, Baker), instead of the subject securely enclosed, is the object of the gaze. Loos’s usual emphasis on the primacy of interiority, instead of offering comfort and covering, here translates into theatricality and exposure.” 6 Perhaps—although there is far too little evidence for any of this, and it must also be said that it is equally possible that Baker herself could have taken on the role of voyeur!

More to the point, it could be argued that the whole arrangement is both voyeuristic and exhibitionistic. It is about seeing and being seen, about movement and discovery. Because the pool is illuminated by the windows and the skylight above, its depths are visible not only from the ambulatory but also from the stair—which is given a broad proscenium—and also from the outside. Moreover, one must walk past the pool to reach two of the main spaces on this level, the petit salon —which is itself a sort of observatory—and the corner café. The whole arrangement is somatic, haptic, visual, and sensual. 7

Beatriz Colomina offers a perceptive reading, one that begins to suggest the multifarious nature of the space alongside the pool. In every Loos house, she writes,

there is a point of maximum tension, and it always coincides with a threshold or boundary. In the Moller house it is the raised alcove protruding from the street façade, where the occupant is ensconced in the security of the interior yet detached from it. The subject of Loos’s interiors is a stranger, an intruder in his own space. In Josephine Baker’s house, the wall of the swimming pool is punctured by windows. It has been pulled apart leaving a narrow passage surrounding the pool, and splitting each of the windows into an internal window and an external window. The visitor literally inhabits this wall, which enables him to look both inside, at the pool, and outside, at the city, but he is neither inside nor outside the house. 8

Colomina is undeniably correct about how Loos creates places of great tension in his designs. But her imagined observer is fixed in place, motionless, the views static and unchanging. Loos’s conception here—and, indeed, elsewhere in his later domestic designs—was assuredly intended to be dynamic. It is not only about a singular viewing experience, but also one that is constantly changing as the subject moves her or his body and head.

The third-floor plan nearly mirrors the floor below, with another ambulatory extending around the pool mostly at water level. There are also two bedrooms, and, along the side of the structure, above the main stair, is the salle à manger. On this floor, too, there are a few shifts in height and the associated short stairs. The movement sequence throughout is otherwise almost ordinary, however. Aside from the imposition of the swimming pool, the spatial play seems understated, even tentative. Compared with the Moller House, it is certainly much less developed.

What is remarkable is the manner in which the views function along the paths, and here comparisons with the Moller House are revealing. At the outset, the path in the Baker House affords little in the way of sensory experience, only what comes with the act of walking and climbing in a straight line, with mostly “ordinary” views (fig. 131 ). At the beginning of the ambulatory around the pool on the second level this changes abruptly. As one would have moved along the narrow corridor, the interior of the pool would come into view, only to be obscured again as one continued on. This process would have been repeated at each of the other three windows. What one would have experienced was a series of visual “shifts,” a cause-and-effect sequence of views set into a temporal chain of openings and closings. On the upper floor, the visual effects continue, as movement and perception elide into a fantastical experience. We have no knowledge at all of what Loos was thinking, but it appears as if the relative simplicity of the path throughout the remainder of the house was a lead-up to this rapid alteration of images and impressions, a means for intensifying these impressions.

Figure 131 Project for a house for Josephine Baker, continuous plan. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Entrance; 2. Hall with skylight; 3. Swimming pool (underwater portion); 4. Café ; 5. Ambulatory and landing; 6. Bedroom; 7. Vestibule; 8. Salle à manger (dining room); 9. Swimming pool (water level); 10. Swimming hall

One other feature of the house’s path is worth commenting on. Exceptionally for Loos, the paths through the house are quite long; the quick, almost frenetic shifts from place to place in his previous Raumplan houses have given way here to an unhurried stroll. This, too, was an experiment he would not repeat—again, for reasons unknown.

But the idea of an extended path does rest at the center of another house of the era, one of the most remarkable of the space-houses of the Viennese modernists: Josef Frank’s Beer House.