CHAPTER THREE

Raumplan and Movement

The idea of a new architecture of space was remarkably present—if still mostly unspoken—in Vienna in 1911. That year the young R. M. Schindler, recently graduated from the Technische Hochschule (where he, too, had come under the influence of Carl König), had a great epiphany.

In the summer of 1911, sitting in one of the earthbound peasant cottages on top of a mountain pass in Styria, a sudden realization of the meaning of space in architecture came to me. Here was the house, its heavy walls built of the stone of the mountain, plastered over by groping hands—in feeling and material nothing but an artificial reproduction of one of the many caverns in the mountainside.

I saw essentially that all architecture of the past, whether Egyptian or Roman, was nothing but the work of a sculptor dealing with abstract forms. The architect’s attempt really was—to gather and pile up masses of building material, leaving empty hollows for human use….

And stooping through the doorway of the bulky, spreading house, I looked up into the sunny sky. Here I saw the real medium of architecture—SPACE.

This gives us a new understanding of the task of modern architecture. Its experiments serve to develop a new language, a vocabulary and syntax of space. 1

By the time he sat down to write his space manifesto–probably in the summer of 1913–Schindler was under the influence of Otto Wagner (he had entered the Wagnerschule at the Academy of Fine Arts in 1910), and he would also attend classes in Adolf Loos’s “Privatschule”. Schindler rejected key features of their ideas, however. In particular, he dispensed with traditional notions of constructional style, monumentality, and comfort. He argued instead for space as a fully constitutive element. 2 Although he would not publish his manifesto for more than two decades (and then in altered form), Schindler’s space idea would aptly describe the modern architecture of coming years: it was to be, put plainly, about open, flowing spaces, their form determined and shaped by their function.

Figure 27 Adolf Loos, Goldman & Salatsch Building, Vienna, 1909–11; photo after 1913. Bildarchiv der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. I. N. 3.528B.

But absent in his conception are the two features that would define the Viennese architecture of our story: movement and subjective response. There were, however, other efforts taking place to mark out the new space. In the same year, 1911, Strnad’s Villa Hock, then nearing completion, offered one formative view of the possibilities of the spatial path; the other came in Adolf Loos’s Goldman & Salatsch Building on Michaelerplatz (fig. 27 ).

Loos had received the commission to design the building in the late summer of 1909. He was by that time already in his late thirties, and it was to be his first important building. He had spent the previous thirteen years, since his return from the United States, writing and carrying out commissions for interiors—most of them for friends and acquaintances.

The clients for the new structure, Leopold Goldman and his brother-in-law, Emanuel Aufricht, were the owners of an exclusive tailor and outfitter firm they had inherited from Leopold’s father. The shop had originally been on the Graben, at the city’s very center. In 1909 they purchased an eighteenth-century building a short distance away on Michaelerplatz, across the square from the Hofburg—the imperial palace—with the intention of moving the business there. They decided to tear down the old structure and erect a modern commercial and apartment building. Their new business was to occupy a portion of the ground floor and all of the second floor.

To select a design, they decided to hold a private competition, with all of the entrants determined by invitation. Loos had previously worked for the Goldman family (he had, in fact, designed the interiors for the first Goldman & Salatsch store, as well as the Aufricht family’s apartment adjacent to it, and he had worked on a house for the younger Goldman and the grave marker for his father); he was asked to submit a design, along with eight others. 3

The exact circumstances of the competition are now clouded. It seems that Loos first declined the invitation, stating that he had found that competitions rarely resulted in the choice of the best design. 4 But when the competition failed to produce a satisfactory concept, Loos sketched a plan, which he showed to Goldman. Goldman saw its merits and asked Loos to take over the project. Because Loos up to that time had never built a building and he was not then a licensed architect, Goldman asked another young but experienced architect, Ernst Epstein, to assist him. Over the next six months, the two men worked together closely to prepare the design. 5

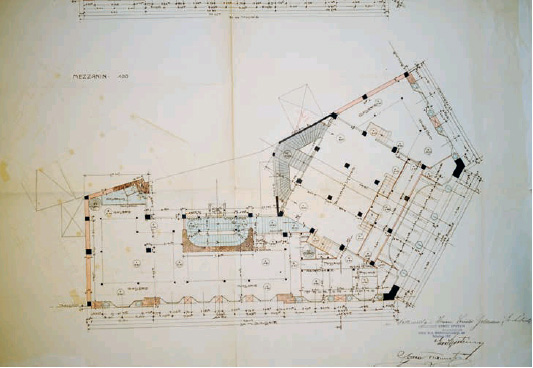

Loos’s original plan for the shop (the remainder of the building was in some measure an afterthought) was probably made in July 1909 (fig. 28 ). It suggests a more or less conventional arrangement, with the Goldman & Salatsch store at the main entrance, flanked by four other ground-floor stores. But another drawing Loos made a short time later, this time of the upper portion of the shop on the mezzanine, reveals the revolutionary nature of his concept (fig. 29 ).

The space was to be shaped into multiple levels, the floors shifted up or down in relation to each other. The heights of each area, in what would be an intricate arrangement, are shown in the drawing. They are a first indication of his idea of employing a complex spatial plan—the Raumplan, as it would become known—of interlocking volumes of varied heights on different levels.

Loos would go on to develop and refine his idea, and when the building and shop within were finally completed in the late summer of 1911 what he had achieved was matchless and remarkable. 6 The entry into the original store was through a tetrastyle portico; it led directly into the large ground-floor showroom (figs. 30 , 31 ). From there, one ascended to the upper floors by means of a central stairway (fig. 32 ). The shop was functionally divided. On the ground floor was the sales area for accessories—gloves, hats, ties, under-wear, socks, and the like—while the upper floors were reserved for making suits, for consultations, fittings, and selecting materials. Housed in these upper spaces were all of the work areas for the tailors and a separate shirt-fabricating room.

Figure 28 Loos, preliminary plan for the ground floor of the Goldman & Salatsch Building, August 1909 (?). Grafische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, Adolf Loos Archive (hereafter ALA) 227.

Figure 29 Loos, preliminary plan for the mezzanine floor of the Goldman & Salatsch Building, dated 11 August 1909. Grafische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, ALA 519.

Figure 30 Goldman & Salatsch Building. Photo by Bruno Reiffenstein, ca. 1930. Bildarchiv der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, I. N. R8528-D.

Figure 31 Goldman & Salatsch Building, main stair within the store. Photo by Martin Gerlach Jr., ca. 1930. From Heinrich Kulka, Adolf Loos: Das Werk des Architekten (Vienna: Anton Schroll, 1931), plate 45.

Figure 32 Goldman & Salatsch Building, view of the stair leading to the mezzanine.

Figure 33 Goldman & Salatsch Building, view of the mezzanine.

Figure 34 Goldman & Salatsch Building, reception space on the mezzanine.

It is on these upper floors where Loos’s revolutionary concept is most fully evident. The mezzanine is essentially split into two levels, with a number of smaller subdivisions. One can see clearly the effect in a diagonal view of the space (fig. 33 ). The various areas are connected by means of short flights of stairs. In some places, as in the reception room, the ceilings are lowered (fig. 34 ). In others, such as the material storage and ordering area or the suit workshop, there are openings in the floors that allow a visual and physical connection between them (figs. 35 –37 ). Some aspects of this design had precedents, but the overall concept was certainly new.

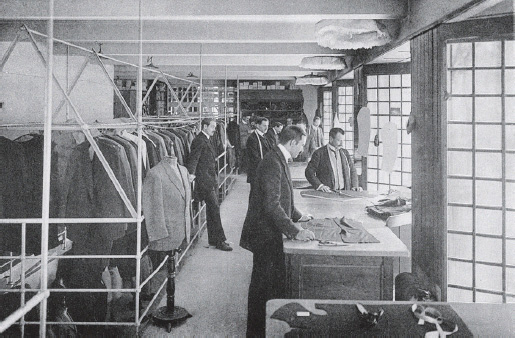

Figure 35 Goldman & Salatsch Building, material storage and ordering area on the mezzanine. Photo from a promotional brochure for Goldman & Salatsch, ca. 1911. Grafische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, ALA 1526/9.

Figure 36 Goldman & Salatsch Building, repair workshop on the lower mezzanine level. Photo from a promotional brochure for Goldman & Salatsch, ca. 1911. Grafische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, ALA 1526/13.

Figure 37 Goldman & Salatsch Building, suit workshop. Photo from a promotional brochure for Goldman & Salatsch, ca. 1911. Grafische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, ALA 1526/12.

Here rests one of the great mysteries of Loos’s work. Where did this idea come from? When precisely did he develop it?

One clue comes in the form of an undated drawing of another project, an atrium house, that Loos seems to have made the same year (fig. 38 ). It shows four stories of what appears to be a taller building with a tower. In the section on the right-hand side of the rendering is an indication of the same kind of spatial play. It is most evident in the transition from the office to the kitchen above, which are connected by a spiral staircase. The rooms are of assorted heights; one in the front (presumably the piano nobile) was taller, while the kitchen and office at the rear are lower—in keeping, it seems, with their less important functions.

Figure 38 Loos, drawing of an atrium house with tower, ca. 1909. Grafische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, ALA 528.

Loos would later point specifically to his desire to build “economically” as the reason he adopted his volumetric scheme. 7 But here resides still another mystery. For an architect who wrote a great deal—and especially well, for Loos was an exceptional writer, one of the very best writers on architecture of the last century—he penned only a few lines about his spatial idea. And most of what he did write comes in the form of a footnote. It appears in an essay on an entirely different topic, a eulogy for his favorite cabinetmaker, a man named Josef Veillich. The piece was written in 1929—long after Loos had developed and realized the Raumplan concept in various works. He mentions the Weissenhofsiedlung, the recent housing exhibition in Stuttgart mounted by the German Werkbund and overseen by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, in which Loos had pointedly not been invited to take part. “I would have had something to exhibit,” he writes with palpable bitterness, “namely the dissolving of the organization of living rooms into space, not on a level surface, story by story, as has been achieved heretofore. With this invention, I would have saved humanity a great deal of work and time in its development.” His statement continues in the footnote: “Because this is the great revolution in architecture: the dissolving of a ground plan into space! Before Immanuel Kant people could not think spatially and architects were forced to make the toilet as high as the formal hall. Only by means of dividing the space in half could they succeed in making lower rooms. And just as we will one day play three-dimensional chess, so other architects will be able in the future to dissolve the ground plan into space.” 8

Loos’s other major statement about the Raumplan idea appeared in late 1911 in a speech defending his design of the Goldman & Salatsch Building (or the Looshaus, as it would become universally known). Referring to the other competition designs (and why his scheme was superior), he said: “The plans [of the other architects] all took into account only the regular horizontal layering of the floors whereas, in my opinion, the architect should think in terms of space, in the form of the cube. Thus, I already had an advantage in the economical use of space. A toilet does not have to be as high as a formal hall. If one gives each room only the height it requires, he can build much more economically.” 9

That is effectively the entirety of what he left us about the Raumplan idea in his own words. There are only two other significant sources that offer insight into his thoughts. One comes in the book his assistant Heinrich Kulka wrote about him in 1931. In a section in the text titled “Der Raumplan,” Kulka presents a longer and more complete version of Loos’s idea. 10 This is the first time, remarkably, that the term appeared in print; Loos never used it in any of his own writings. Whether Kulka formulated the term or whether he took it over from Loos remains one of the undiscovered chapters of the emergence of the new space.

Kulka was then still working for Loos. He had studied with Loos around the end of World War I and began assisting him in the mid-1920s, overseeing many of his later projects. During the last years of Loos’s life, Kulka spent a great deal of time with him, and he must have conversed with him at length about his thoughts and motives concerning his designs. What Kulka writes thus must be a very largely, if not wholly, accurate version of Loos’s space concept. Some of the language is even reminiscent of Loos’s speech patterns, suggesting that Kulka may have partly transcribed—or remembered—a discussion or discussions he had with him.

Kulka at one point offers a capsule definition of the Raumplan, the only one we have from that time. It is, he writes, about “thinking freely in space, the planning of spaces resting at different heights and that are not joined to any regular system of the horizontal layering of floors, the composing of connected spaces into a harmonic and inseparable whole and a spatially economical entity.” 11 He also repeats Loos’s assertions about his desire to build “economically,” arguing that Loos had mastered this technique.

Depending on their purpose and importance, the spaces not only had varying sizes but also varying heights. Loos can use the same amount of building material to create more living space, because in this way in the same building envelope, the same foundation, under the same roof, inside the same exterior walls he can make more spaces. He makes the absolute most of the available building material and the building site. 12

This adds little to what Loos himself had written. There is, though, one surprise in Kulka’s text. He provides a brief description of how Loos purportedly had come to the Raumplan idea. It has to do with theaters. Loos had observed something (one assumes while he was attending a play or an opera) that was notable about such spaces: “Theaters had stacked galleries, each one floor high, or adjacent spaces (loggias) that were visibly linked to the various stories of the main space. Loos recognized that the ceilings of the loggias were uncomfortably low if one was not looking out into the large main space, that by means of a connection with a taller principal space one could save space with a lower adjacent space, and he used this insight in building houses.” 13

There are two distinct parts to this observation. One has to do with Loos’s stated desire to use the Raumplan to “save space.” Kulka observed that there was also a subjective element: the loggia spaces were “uncomfortably low,” and this could be remedied by providing visual access to a larger volume. In the Goldman & Salatsch store, this design strategy seems to be present in multiple places. Along the edge of the reception space, for example, the lowered passage looks out onto the full-height portion of the mezzanine (fig. 39 ). Loos’s desire to build economically is also easily readable, for instance, in the office space, which also has a lowered ceiling (fig. 40 ).

Figure 39 Goldman & Salatsch Building, upper mezzanine.

Figure 40 Goldman & Salatsch Building, view from the mezzanine office looking back toward the stair and the material storage area.

Yet Loos must have had other intentions, for the spaces are too unconventional and too specific to have been the product solely of his economical imperative or the notion that a lookout could redeem a lowered space. What is unavoidable to anyone now walking through these spaces is a realization that Loos, very much like Strnad, introduced a complex sequencing of visual and other sensory experiences to heighten one’s awareness of the architecture. The Looshaus, like Strnad’s Hock and Wassermann houses, was an effort at making what might be termed an “affective path.”

“Affective” here—stirring moods or feelings—relates, of course, to the concept of empathy. It implies an experience of something and an accompanying emotional response. That it is linked to “path” is the second element—movement and how movement can heighten experience. That this feature is present and observable in many of Loos’s Raumplan designs is indisputable. But his full intentions are much more difficult to get at, for he writes little about this idea.

We have another source concerning Loos’s Raumplan ideas, however, that sheds light on the issue. It comes from another of Loos’s assistants, the Czech architect Karel Lhota, who worked for him in the late 1920s and early 1930s. He, too, quotes Loos on the Raumplan: “I do not design plans, façades, sections, I design space. Actually, in my work, there is no ground floor, upper floor, or cellar, there are only connected rooms, anterooms, and terraces. Every space requires a specific height—the dining room a different one from the pantry—and for that reason the ceilings lie at different heights.” 14

This is a bit different from what Loos had said or written before. What comes next provides an essential clue: “Accordingly, one must connect these rooms with each other so that the transition is imperceptible [unmerklich ] and natural, but also as practicable as possible. That is, as I see it, for others a secret, for me obvious.” 15

The path thus, in this formulation, is about making “quiet” and intuitive linkages between spaces, which, at the same time, should be functional and sensible. Loos says nothing else, though, nothing that might have given us insight into his thinking or his strategies—other than that for him it was all “obvious.”

In the quotation from Lhota, he goes on to describe the origins of his space idea: “I discovered this spatial solution [raumlösung ] years ago for the Goldman & Salatsch store.” 16 But it was already present, he continues, “in the competition project for the War Ministry building in Vienna, in which the middle portion was arranged into large rooms, with the offices with lower stories arrayed around them, an enormous saving of space—but no one noticed it.” 17

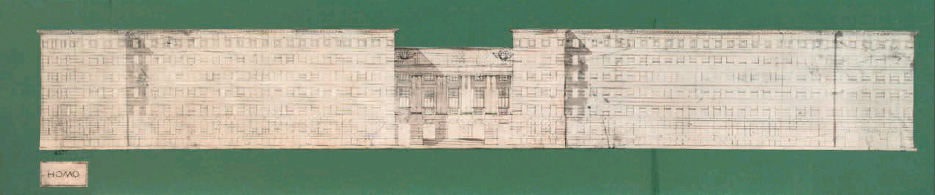

Loos had worked on his entry for the War Ministry competition in 1907 and 1908. The jury rejected it out of hand, because, as Loos’s biographers Burkhardt Rukschcio and Roland Schachel would write later, “in general [it became] the target of a strong criticism, even derision” for its radically simplified massing and façades. 18 The submitted elevations, however, show precisely what Loos was describing: a three-story central tract, with six-story blocks on either side (fig. 41 ). It was an inauspicious beginning, but there are no earlier indications of a Raumplan in Loos’s designs. His idea must indeed have had its genesis around 1907.

Figure 41 Loos, project for the War Ministry Building, Vienna; elevation. Grafische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, ALA 376.

Loos’s argument for the Raumplan, though, was firmly rooted at the outset in his claims for economical use of space. He says nothing at this time about the experience of the transitions from one space to another (those for his War Ministry entry seem to have been little more than perfunctory), nothing that would aid us in understanding the more complex movement sequences in the Goldman & Salatsch store, much less his later houses.

To argue, thus, for an intentional subjective aspect on Loos’s part in the Raumplan is far from easy. Loos offers us little else to support such an assertion. But there is a related statement in the well-known passage from his essay “Architektur” about the “emotional” role of architecture: “Architecture awakens moods in people. The task of the architect therefore is to emphasize these moods. A room should appear comfortable, a house livable. A court of justice should appear threatening to those harboring secret vices. A bank building must say: Here your money is well and safely kept by honest people.” 19 In the same section, he goes on to acknowledge that many of these subjective associations are culturally or personally relative: “The architect can only achieve [these linkages] in those buildings if people are already predisposed to them.” 20

The wellspring of this notion of “architectural moods” extends further back in Loos’s writings. It first appears in his essay “Das Prinzip der Bekleidung” (The Principle of Cladding), published in 1898. 21 He argues that the “task of the architect is to produce a warm, livable space.” Only when this is understood should the architect create a constructive frame. Loos complains that in practice this necessary ordering of tasks is too often ignored: “There are architects who do this differently. They do not imagine rooms but walls. What is left over after building the walls are the rooms.” But “the artist, the architect,” he continues, “first feels the effect he thinks of producing, and he sees with his creative eye the spaces that he wants to create. The effect he wants the viewer to have, whether it is fear in the case of a prison, the fear of God for a church, fear of the state for a government building, piety for a grave, hominess for a house, gaiety for a drinking establishment—this effect will be fostered by means of the materials and the form.” 22

Loos’s thinking here is almost assuredly derived not from Schmarsow but from Semper, and specifically from Semper’s Bekleidungstheorie —his theory of cladding, which Semper had laid out most fully in Der Stil. 23 But Loos appends nothing else that offers insight into how he conceived of the connections in his Raumplan designs, nothing about what he wanted people to experience. Nowhere does he make mention, directly or indirectly, of Schmarsow, Vischer, Hildebrand, or any of the other German theorists of the previous generation—aside from Semper.

Was Loos aware of their ideas? By 1909, the year he began working on the design for the Looshaus, these theories, as we have seen, were beginning to permeate the world of architectural discourse in Vienna. It is even possible that Loos may have discussed them with Strnad since the two men were on friendly terms. But there are no sure indications either way.

Figure 42 Loos, submitted plans for the Goldman & Salatsch Building showing the ground floor, dated 11 March 1910. Plan-und Schriftenkammer der Magistratsamt (MA 37), Vienna.

Figure 43 Loos, submitted plans for the Goldman & Salatsch Building showing the mezzanine level, dated 11 March 1910. Plan-und Schriftenkammer der Magistratsamt (MA 37), Vienna.

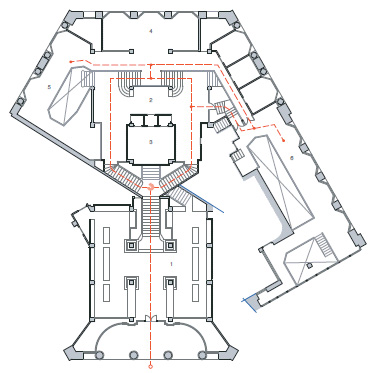

The evidence for Loos’s intention to foster an affective path in the Goldman & Salatsch store—the only good evidence—is visual, expressed in the building itself. It is not notably apparent in the original drawings. The set of renderings—all drawn, it seems, by Epstein—that Loos submitted to the building authorities only hints at the complex spatial ordering in the transition from the ground floor to the mezzanine level (figs. 42 , 43 ). Redrawing these spaces in plan provides little additional indication of the nature of the spaces above or of the paths (figs. 44 –46 ). And there are no sections surviving in either Loos’s or Epstein’s hands, which is in itself surprising. Loos seems to have designed the tangled plan as a mental image—without bothering to render it in section. Even in section, though, it is nearly impossible to grasp the effect. It is the sequencing of the spaces that is revealing: movement through the building itself is a document, a record of his intentions.

Figure 44 Goldman & Salatsch Building, ground-floor plan, 1:200. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Main shop floor (men’s outfits and accessories); 2. Retail space; 3. Courtyard.

Figure 45 Goldman & Salatsch Building, lower mezzanine plan, 1:200. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Reception area for the tailor shop; 2. Accounting; 3. Fabrics; 4. Office; 5. Sewing workspace; 6. Ironing.

Figure 46 Goldman & Salatsch Building, upper mezzanine plan, 1:200. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Lounge; 2. Fabrics; 3. Dressing rooms; 4. Tailor workspace.

The main path commences at the entry. In the porch, Loos introduced large, curving sheets of glass below and smaller, beveled panes above to create a sparkling light effect (fig. 47 ). Inside, the main route leads up the central stair. The path at this point is compressed, framed by the pillars and vitrines. From there, the stair splits into two parts, winding up to the left or the right. Here the play of space and light becomes much richer (fig. 48 ). Made up of Luxfer prisms, the ceiling produces a glittering of light, which is amplified by the large mirrors at the rear. 24 The mirrors, in turn, offer a first glimpse of the mezzanine above, a preview of the intricate array of spatial impressions to come. Then, as the path continues along the first level of the mezzanine, the space and the view are reduced again, framed by the walls of the upper levels (fig. 49 ). At the end of this passageway the outlook opens up once more, granting the viewer a full sense of the myriad spatial possibilities (figs. 50 , 51 ). Along one of the possible routes from this point one can first see the tailor’s work area above and below (fig. 52 ).

Figure 47 Goldman & Salatsch Building, view of the porch.

Figure 48 Goldman & Salatsch Building, view of the stair leading to the mezzanine.

Yet it is only through movement—through the act of walking and climbing, and by means of moving one’s head to take in the different vistas—that the space begins to become understandable. A stationary observer cannot possibly grasp the full spatial ordering, just as a ground plan offers only a partial reading of the spaces.

Figure 49 Goldman & Salatsch Building, entry to the mezzanine.

Figure 50 Goldman & Salatsch Building, lower mezzanine.

Figure 51 Goldman & Salatsch Building, view from the lower mezzanine to the changing areas above.

Figure 52 Goldman & Salatsch Building, view from the lower mezzanine to the tailors’ workspace above and below.

The difficulty of representing in drawn form what is occurring is notable and revealing. For all the complexities of Strnad’s two prewar villas—for all of their discontinuities and disjunctures—a set of ground plans can convey reasonably well most of what is going on along the entry path. Even if the visual and somatic experience cannot be completely reproduced from looking at a graphic representation, one can mostly imagine it. This is not true of the Looshaus. The paths are too intricate and the views too varied.

Figure 53 Goldman & Salatsch Building, continuous plan showing the path through the store, 1:200. Drawing by Nicolas Allinder. 1. Main shop floor, men’s outfits and accessories; 2. Reception area for the tailor shop; 3. Accounting; 4. Lounge; 5. Fabrics; 6. Tailor workspace.

It is possible, however, to communicate more fully the nature of this kind of space, if a different sort of rendering is employed—a “continuous path plan,” a graphic linking together of the route, which shows the unbroken route on multiple levels (fig. 53 ). 25 Essentially, this is a series of linked ground plans, the connections between the plans occurring at the place where the path aligns. On the one hand, to render this way is a distortion—a visual contrivance that is more akin to a diagram than a drawn version of reality. Yet by representing the path as a line extending as a thread throughout, the movements and possible vistas become at least more readily manifest.

Yet what a plan—even a continuous one—cannot demonstrate completely is Loos’s seeming desire to engage the observer’s spatial awareness. Even more, it cannot disclose his intention to provoke the observer’s emotional responses because much relies on other factors, such as lighting, materials, and finishes. In the case of the Goldman & Salatsch shop, there is the obvious appearance of luxury and exclusivity—unquestionably the right impression for such an establishment. Loos’s manipulations of light, the continual spatial compression and then opening up, were doubtless also part of his desire to develop full architectural awareness—to foster multiple and divergent “moments” along the main path. There are the repeated changes in direction inherent in the spatial sequence, and they prompt a somatic as well as a visual experience. This is reinforced in the many short flights of stairs. Strnad’s notion of employing disruptions to enhance the viewer’s mindfulness of the built world is very much in evidence here. In the mezzanine space, they come about through the many abrupt shifts in direction along the paths, and, also, by means of the many short flights of stairs.

Despite the lack of any specific commentary on Loos’s part about his intentions, a few things do seem clear. The spatial ordering of the Goldman & Salatsch shop is an attempt to enhance its functionality. And it is simultaneously an effort to make a new kind of spatial experience. In the initial planning stages, we know that Loos worked closely with Goldman to ensure that the arrangement of the spaces would make for an efficient flow of work and serve the needs of the gentlemen customers. That Loos’s plan was significantly better in this regard than the other submitted designs appears to have been one of the principal reasons he received the commission. 26 And Goldman, from all that we know, was quite pleased with the result.

From our remove, the question of just how functional and economical these spaces were is still open. Moving about the mezzanine during the course of a normal workday would have entailed a considerable amount of going up and down stairs. It would have been physically demanding, and some of the routes are less direct than they could have been. At the same time, Loos’s meticulous portioning of spaces by function probably worked well. The obvious divisions between the areas where gentlemen were received and served and the workspaces provided the necessary level of decorum. Yet their adjacency would have made it quick to move back and forth.

Loos from all indications appears to have thought about functionality quite broadly. It was the function of the mezzanine not only to allow for the fitting and making of clothing, but also to please the customers. The mahogany, brass, and glass fittings evoked the look of the best tailor shops on London’s Savile Row, the model for the shop in the first place. The main stair from the ground floor and the cutting up of the upper spaces into smaller zones gave the fitting areas a feeling of separation and intimacy—precisely the right mood for those places where the gentlemen were served and where they would change in and out of clothes. If Loos had achieved only this, his design would have been a success. His sequencing of spaces, the precise routing of the paths, however, also promoted a feeling of venture and newness. His work held within it a sense of the familiar, of luxury and privacy, and also of unfamiliarity—a changed mode of spatial recognition that provoked novel sensations and emotions.

The possibilities of manipulating such sensual emotionality would in some part drive Loos’s spatial experiments for the next two decades.