Chapter 7

Insolvency and the Law

In 2010 I was liquidating a lumberyard for the bank and owners; it's not unusual for a beleaguered entrepreneur and bank to agree to a voluntary liquidation in exchange for something like releasing the entrepreneur from a personal guarantee. We were selling off inventory and had already contracted an auctioneer to sell off whatever remained after 30 days. I got a call from a local business owner who had recently sold a bunch of product to the store but was never paid. My heart went out to the guy; he'd gotten screwed. I explained the situation, that the secured lender (bank) had liened every asset and was still likely to come up short, so there would be no recovery for him. He said, “I was just in your store, I've seen my product on your shelf, let me just take it back and sell it to someone else.” Gosh, it made so much sense and I really felt for the guy, but the inventory, his product, now belonged to the bank. They had the liens on it.

“No, it belongs to me! I was never paid for it,” he declared.

“Well, actually not. It belongs to the bank,” I responded.

You can imagine his response.

I explained: “They ordered, you delivered, and you delivered on credit terms. You transferred the ownership to them when they obligated themselves for it and they gave you a receivable in exchange. In doing that you completed the transaction and subordinated your interests to that of the bank. I know, this is the downside of vendor financing, and it is terrible. If it makes you feel better, have your attorney call me and I'll explain our situation to him.”

He didn't like it and neither did, I but that's how the law is written and you're not going to change it.

The United States deals with distressed commerce through two sets of laws. There is the U.S. Bankruptcy Code that is federally administered through U.S. Bankruptcy Court. There is also the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) that states interpret in their courts. Until a business enters the federal bankruptcy system, they operate under the Uniform Commercial Code and other state laws.

So what is distress and how do you know if you're in it? The technical term is the zone of insolvency, which is a strange gray area that often defies conventional wisdom. Normally management has a fiduciary duty to the shareholders, and that's how they conduct themselves. But in an insolvency that duty expands to include creditors, in addition to shareholders and the corporation. Said another way, the shareholders have failed to adequately protect the creditors, and now they must act also in the best interest of the creditors. There are few clear markers on the path to insolvency, but it can be argued that one day you were running the business normally and the next day rights and duties shift. Perhaps, it's because your biggest customer didn't pay you and you're cash‐broke. But the next day you collect a bunch of cash and you're no longer insolvent, sort of. You can see the murkiness here.

Insolvency is defined as either cash‐flow insolvency, when you can't, or don't, foresee the ability to pay your bills on time. Any entrepreneur knows that most small businesses move in and out of that ability over the course of a month. And how would you define it? A conservative cash‐flow forecast might show a path toward insolvency while hopeful projections wouldn't. This could simply be the difference between how a CPA and an entrepreneur interpret the same set of facts.

Balance sheet insolvency is the other type of insolvency, when your liabilities exceed your assets. It is argued whether this is all balances or just current balances. Or, whether we use liquidation values or book values. Should we even consider goodwill or leasehold improvements, which have no liquidation value but often keep a balance sheet positive? Interestingly, most startups would be defined as balance sheet insolvent, which again illustrates how fuzzy the definition of insolvency can be.

As discussed in Chapter 1, the hierarchy of creditors is one of the best‐named laws ever: the Absolute Priority of Debt Rule, which is codified in federal bankruptcy statutes. Most collectors don't understand this (and even many commercial and collection attorneys act like they don't fully understand it) so I get to remind people that the rule is named such because it is both Absolute and Priority and they really should quietly wait in line while we try to fix the business.

Liquidation value versus going concern value is another way of valuing a company and shows the stark reality of value erosion that (almost certainly) entrepreneurs and (likely) banks have ignored. The following values represent a healthy economy with healthy equipment values.

Figure 7.1 shows the destruction of value as a business slips into insolvency.

| ACME Mfg. – Loss of Value in Insolvency | ||

| Account | Book Value | Liquidation Value |

| Cash | – | – |

| Accounts Receivable | 1,000 | 800 |

| Inventory | 2,500 | 625 |

| Total Current Assets | 3,500 | 1,425 |

| Machinery and Equipment (net) | 1,800 | 1,200 |

| Intellectual Property | 500 | 20 |

| Furniture and Fixtures | 200 | – |

| Computers and Software (net) | 700 | 10 |

| Leasehold Improvements (net) | 800 | – |

| Goodwill (net) | 1,300 | – |

| Total Long‐Term Assets | 5,300 | 1,230 |

| Total Assets | 8,800 | 2,655 |

| Liabilities in Priority Rank | ||

| First Bank Revolver | 2,100 | 2,100 |

| First Bank Term Note, SBA‐backed | 1,500 | 1,500 |

| Second Bank – Cash Advance Loan | 250 | 250 |

| State BDC Loan, no PG | 100 | 100 |

| Family Loan | 1,000 | 1,000 |

| Accounts Payable | 1,500 | 1,500 |

| Total Liabilities | 6,450 | 6,450 |

| Equity | 2,350 | (3,795) |

Figure 7.1 Liquidation value.

Entrepreneur balance sheets are often overstated for a variety of reasons; bad accounting and ownership fantasy are the main causes. Over time, errors on the asset side of the ledger stack up, usually with a CEO who doesn't quite understand the underlying accounting issue but is happy to see equity increasing. The bank underwriters understand all the accounting issues and are only partially deluded over time. It's not uncommon for a lending officer (sales department) to look at the balance sheet (see Figure 7.1) during a review, nod his head approvingly about $1 million in equity, and move on, never really noticing how weak the balance sheet actually is. The dilution of value on a balance sheet as it nears insolvency is silent and unseen but it can add up to a considerable shortfall in a liquidation, primarily in the following ways:

- Receivables are automatically worth less in a liquidation because they become harder to collect when the customer–vendor relationship is ending. Collectors also need access to clean and current accounting records, which can be hard to come by in a liquidation. Also, customers use the liquidation as an excuse not to pay, and they don't like paying banks. Although the cost of collection goes up, results decline, and this reduces the recovery on this most‐liquid asset.

- Inventory loses value quickly without customer demand. Finished goods may be sellable, or not, whereas WIP (work in progress) is probably worthless (who wants a half‐built anything?) and raw‐material inventory usually only has scrap or high‐return‐cost value.

- M&E (machinery and equipment) immediately loses value. The cost of a liquidation auction might be 25% all in, and that's subtracted from the value received at auction. This can result in a steep decline from the book value listed on the balance sheet.

- Intellectual property is almost always overstated on a balance sheet. It might contain a few patents, of limited remaining shelf‐life and of limited value, though there may be brands. It's common for entrepreneurs to rave about the value of their patents or brand names even though they have yet to extract profit dollar number one from them. Trademarks, copyrights, and so forth have little attributable value in a distressed business.

- Furniture and fixtures are worth nothing or close to nothing in a liquidation. I've knocked myself out trying to sell really nice office furniture and have probably never exceeded 10% of the original purchase price. The last liquidation I did we just abandoned the furniture and fixtures (F&F) to the landlord. One crazed CEO, spent $20,000 per office on furniture and another $500,000 on black walnut conference room paneling. All of which netted zero in liquidation.

- Computers, well you know how fast they lose value. A two‐year‐old PC work station might be worth $50 on Craigslist? The software license cannot be transferred, so it's hard to gain value from that investment.

- Leasehold improvements? Well that was your special gift to the landlord because you can't sell them or take them with you.

- Goodwill is hangover from a former acquisition that, apparently, has left little real value on the balance sheet.

What keeps an insolvent business above auction value is a pulse, any form of ongoing life or activity in the business. This is called going concern value and is covered in Chapter 9.

Corporate distress is a fact of life and economies have found productive ways of dealing with these issues over the years. The U.S. Bankruptcy Code is considered the best around and what other nations seek to replicate in their own countries. In Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution, our founding fathers called for bankruptcy laws to be written. America had broken free of Britain and memories of the horrible debtor's prisons in England inspired a feeling that society is best served when honest but unfortunate people and businesses are provided a fair and final release. Before we get too deep in the weeds on the rules of modern day bankruptcy, let's review the concept of insolvency and how it's been handled through millennia.

History of Bankruptcy

Leviticus 25:10 in the Old Testament, New American Standard translation, proclaims:

You shall thus consecrate the fiftieth year and proclaim a release through the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee for you, and each of you shall return to his own property, and each of you shall return to his family.

This verse is accepted to mean that every 50 years property will be released from debt, indentured servants released from obligation, and slaves released from captivity. Let me focus on my interpretation of the debt part here, and let's consider debt as it existed before the laws and limits we know today in the United States, when debt calculations were not uniform, interest not regulated, and so on. How would people be protected from predatory debt practices? How would people, families, and even tribes be protected from what could become generational indebtedness? The Lord's solution was simple, a jubilee in which all debt must be fully released every 50 years. This allowed debtors a “fresh start,” and it modulated the greed of creditors who knew that eventually they would be back to zero. In one simple verse, it created balance. Today the U.S. legal system has achieved a similar (but uneasy) balance, though with far more detail and not nearly such a long wait.

My understanding of history is that Mosaic Law (Law of Moses) called for a sabbatical year that provided the release of all debts owed by members of the Jewish community, not gentiles, every seventh year. (Remember, Moses predated political correctness, so this sort of discrimination did happen.)

In ancient Greece a man and his family could be forced into debt slavery until the debtor repaid his debts through physical labor. The modern‐day version of this might be working in the kitchen when you can't pay for your meal. Back in ancient Greece city‐states enforced variants on this theme with limits usually around five years and protection of life and limb for debt slaves, a benefit not enjoyed by physical labor slaves.

The term bankruptcy comes from the Italian banca rotta, which means “broken bank” though many translate it as “broken bench.” The common story I hear in the insolvency community is that in ancient Rome when a merchant did not pay his debts (and we assume failed to provide a specific plan to satisfy his creditors) his merchant bench would be broken, putting him out of business in the market and making a public statement for other merchants.

As you might imagine, Genghis Khan dealt with bankruptcy more seriously. His Yassa (book of laws) mandated the death penalty for anyone experiencing insolvency three times.

England formally dealt with insolvency in the Statute of Bankrupts published in 1542. In grade school, I learned about debtor's prisons in England in which debtors would be forced into a cruel and ironic purgatory of sitting in prison until they repaid their debts – with, of course, no way to earn money to repay those debts. Modern‐day China, I am told by an American who recently fled a bankruptcy there, will “detain” registered agents of insolvent companies, giving them the inside of a locked room and a phone to fundraise for the amount owed. This could amount to years of dialing for dollars and hoping for release.

Conventional wisdom is that the U.S. founding fathers, after earning their independence from Britain, were determined to do things right in America. Although they had a long list of grievances with Britain, bankruptcy must have ranked pretty high since it was called for in Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution. Article I, Section 8, Clause 4; “The Congress shall have the Power to … establish … uniform laws on the subject of Bankruptcies throughout the United States …”

Bankruptcy laws were established as America's nascent economy grew, and these laws continue to be updated over time. The first U.S. bankruptcy laws were established in 1800, the second laws in 1841 in response to the financial panics of 1837 and 1839. The third bankruptcy laws were established in 1867 in response to the panic of 1857 and the Civil War.

Perhaps the most fascinating development in U.S. bankruptcy law came during the age of railroads. Bondholders supplied much of the debt needed to finance these massive projects and collateralized their debt with sections of rail. When railroads failed to make bond payments, the bondholders were entitled to foreclose on and liquidate those sections of rail. Imagine a railway from New York to Pittsburgh and some bondholder wants to rip up and sell off (for scrap value) 20 miles of track near Altoona. This action would destroy value to the entire line, to all debt and equity holders, as well as to the larger economy.

Isaac Redfield in his 1859 Treatise on the Law of Railways explained: “The railway, like a complicated machine, consists of a great number of parts, the combined action of which is necessary to produce revenue.” Courts, understanding that combined action along with the impacts of contagion damage and the semi‐public nature of railroads, applied principles of reorganization to deal with these insolvencies. The Bankruptcy Act of 1898 and its amendment in 1933 allowed for the reorganization of railroads, corporations, and individual debtor agreements. This provided what is the most significant part of bankruptcy law in my line of work – reorganizing broken companies.

Although U.S. bankruptcy law is well established and emulated, some nations are just now coming to grips with the concept. The United Arab Emirates just created a bankruptcy law in 2016 and Saudi Arabia has announced it will introduce a bankruptcy law in 2018. “The measure not only aimed to remove the threat of jail for executives of business in distress but also to increase the foreign financial inflows in the country.” Yes, the threat of jail remains how distress is handled in many developing nations. (Startup MGZN, September 24, 2017)

Modern‐Day U.S. Bankruptcy Law

Avoid bankruptcy if at all possible. It is expensive, demanding, fraught with risk, and almost everything that can be accomplished in bankruptcy court can be accomplished out of court through persuasion. Although bankruptcy may save your skin as a last resort, it is often better used as a threat, direct or unspoken, than as a directed course of action. Expect a minimum cost of $100,000 for a Chapter 11 filing, though we're currently involved in the bankruptcy of a $70 million revenue company that has already spent over $9 million on legal fees.

Bankruptcy law is complicated and a little bit murky. A bankruptcy attorney friend of mine says that murkiness appealed to him as he was selecting a specialty of practice. “Insolvency allows for a lot of interpretation and I thought that would allow me more creativity and challenge in my practice. Plus, insolvency is so counterintuitive that commercial attorneys simply don't understand it, and that gives me a huge leg up in insolvency issues outside of the bankruptcy court.” Personally, I'm intrigued by any area of law that uses such intimidating terms as absolute priority, cramdown, and strongarm powers.

I am not an attorney, so I've found simple ways of understanding bankruptcy's modern‐day structure and how it works. In short, there are two types: reorganization and liquidation. Reorganization (Chapter 11) is basically calling a time‐out, reducing secured debt to the value of the collateral securing it, reducing or eliminating unsecured debts, dumping unprofitable leases or contracts, and coming out the other end with a clean balance sheet. Those remnants might be your business intact, just as planned, or it may be much less because you didn't have a good plan. But overarching all these machinations are the personal guarantees, such as the ones I signed in my youth, which will generally not be adjusted by a corporate restructuring. The guarantor will have to reckon with these in one manner or another after restructuring.

Liquidation (Chapter 7) is simply that; the auctioneer is called in, employees are terminated, properties abandoned. But opportunities may exist for stakeholders to acquire valuable assets at bargain prices from the trustee. The renowned outdoor equipment company Black Diamond was founded on assets purchased by its employees after product liability lawsuits forced the original business into bankruptcy (that was an 11, not a 7, but nevertheless a liquidation).

Reorganizations are handled differently among various groups, as a family farm with a failing crop should be treated with different nuance than when, say, the city of Detroit files for bankruptcy. Although these cases can vary dramatically, they mostly have one thing in common – a cadre of divergent stakeholders with vastly differing interests who must be corralled, cajoled, or litigated into cooperation by the plan proponent's counsel.

Exhibit 7.2 helps explain the general structure of bankruptcy chapters in the U.S. Code.

The missing chapters in Figure 7.2 are all part of Title 11 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code. Chapters 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 no longer exist because they were either repealed or consolidated into other chapters. Chapters 1, 3, and 5 provide for definitions, administration, and a more thorough explanation of creditors, debtors, and the estate.

| Chapters in U.S. Bankruptcy | |

| 7 | Liquidation, any and all |

| 9 | Reorganization for municipalities |

| 11 | Reorganization for corporations |

| 12 | Reorganization for family farmers and fishermen |

| 13 | Reorganization for individuals |

| 15 | Reorganization of U.S. operations of foreign companies |

Figure 7.2 U.S. bankruptcy chapters

Chapter 11: Corporate Reorganization

We are surrounded by companies that have survived only through Chapter 11. These include massive energy companies, national retailers, railroads, airlines, municipalities, and, of course, the real estate empire of a certain politician. Chapter 11 is how Hostess got restructured and was able to regain health. Companies in the airline and retail industry often restructure under Chapter 11 repeatedly and are sarcastically referred to Chapter 22 or 33 filers. Consumers are apparently unconcerned about flying on an airline that is under bankruptcy protection. The legal construct of this process is why companies like Quicksilver, Aeropostale, Chrysler, General Motors, Delta, United, US Air, and Chuck E. Cheese are all still in business as I type this. Clinically, it is fair and increasingly efficient but also costly, risky, and uncertain.

Although Chapter 11 remains a useful tool of last resort, the number of filings and the industry as a whole has been on the decline in the last two decades. Part of this is because lenders have wised up and are drafting bankruptcy resistant loans and partly because of the astronomical expense of a complex restructuring. The filing company, or debtor, generally pays most of the bills on all sides. Your ripped open company is now funding your lawyers, your bank's lawyers, the creditor's committee's lawyers, US Trustee fees and so on. Plus, all parties are likely using a financial advisor and the business is often paying for all of that. And if the debtor is not paying it, the various creditors are. It can be an obscene feeding frenzy of professionals that further drains an already struggling company. In a contentious bankruptcy, you are funding the other side's accusations against your management, which become part of the public record, that you are paying for. It is not for the faint of heart.

Entrepreneurs who personalize the business and its situation have an awful time in Chapter 11. Every part of the process feels like a personal affront, and entrepreneurs spend more time fighting their attorneys and the process rather than taking this rare opportunity to get their houses in order. Rather than minding your business fundamentals, you are learning about cash collateral budgets, defending variations in expected cash flows, and learning about the arcane laws governing absolute priority and the like.

However, wherever there is adversity, there often lies opportunity. More experienced entrepreneurs see bankruptcy as the chance for a thorough cleaning and likely part of a larger strategic plan. Two very clever entrepreneurs I know grew their business on debt then restructured it away in Chapter 11 as growth stalled. They ended up with a healthy, leaned‐down business, a clean balance sheet, and retained 100% control. Again, the lack of or limitation on personal guarantees affords one greater flexibility in such a strategy.

The craftiest capitalists see Chapter 11 as a tool to take over train wrecks and then perform radical surgery on the business, bringing it out lean and clean. These investors have 100% of their energy and emotion focused on the future state of the business – and no personal guarantees with which to contend. This keen ability to see opportunity in carnage and understand how to both fix the business and use the rules of the game to your advantage can net healthy returns.

Bankruptcy can be used as a weapon by both debtors and creditors. Creditors can ally and force the company into an involuntary bankruptcy. If caught flat‐footed, the company can be ripped apart in liquidation, with recovery to the creditors but the loss of jobs and community vitality. In the role of chief restructuring officer to businesses I've been threatened with an involuntary bankruptcy several times, but it always seems to be from a half‐informed unsecured creditor that knows just enough to cause damage. This is probably why it takes two to three undisputed, unsecured creditors to force an involuntary bankruptcy, the logic is that it's hard to find and coordinate that many self‐destructive loons. And if the threat is carried out, the target of an involuntary bankruptcy can deftly convert the case to a Chapter 11 and quickly turn it to its advantage. In large complex capital structures, investors can seek to purchase the fulcrum securities and then force the company into bankruptcy, thereby gaining inexpensive equity control of the business post restructuring.

Debtors can use bankruptcy, or even the threat of bankruptcy, as a weapon to accomplish their goals. Let's face it, simply retaining a bankruptcy attorney is moving onto offense. Threatening a collector with a filing is like a quick jab to the nose that carries the risk, cost, and uncertainty of your options. Filing bankruptcy like the two crafty entrepreneurs I mentioned earlier was a preemptive attack on their creditors. When the tides turned, they figured out how to leave someone else holding the bag. Bankruptcy is most often used as a defensive weapon (a shield) by the debtor to get relief from its creditors. Like a handgun, sometimes just the sight of it is enough to get your point across, without having to deal with messy consequences. But to make this sort of threat effectively, you need to retain legal counsel who knows what they're doing and who has the chops to execute, if necessary. Otherwise the threat will ring hollow.

All these considerations regarding Chapter 11 can best be summed up by the simple notion that if you are playing ball on your toes, you'll see lots of options and control the outcome. If you're playing on your heels, you're going to lose. Too many bankruptcies are filed reflexively or out of desperation rather than strategically. That is why Chapter 11 restructurings typically have a 70% chance of failure. Competent Chapter 11 counsel (who have the luxury of time) will draft the plan of reorganization and size up all the parties before they ever push the button to file the case.

Bankruptcy at its core is about disclosing to the world the machinations of your business and revealing all the mistakes you have made – so it takes fortitude. If done correctly, you will maintain control of your assets and business and ultimately restructure your balance sheet to create an entity that can bring value to your stakeholders, including equity. However, there are dozens of pitfalls that can leave you surrendering control and leading to liquidation. You prepare lengthy schedules of every single entity the business owes money to and every single asset with which those creditors might get paid. It sounds clinical and it is. As an entrepreneur it used to be you and, well, everyone else. It was you on the top of the hill and your employees, customers, and vendors all there cheering for you. In bankruptcy it's you but on a medical examination table being poked and prodded by clinicians in what can feel like a very humiliating manner. You need a talented surgeon to take you through to the other side.

The Players

Like a game of chess, bankruptcy has many different “pieces,” each with limited moves and limited powers playing in the same forum. Understanding who's in the game, whose side they're on, and what they can do to you is critical and confusing. In the bankruptcy auction for the assets of retailer Smith & Hawkin, a very well positioned strategic buyer backed out of the bidding saying, “I'm not comfortable being here. Being in this courtroom is like being in Middle Earth. All of you folks know each other and speak this mysterious language that only you can understand.” As you'll see later in this chapter, it's not nearly that confusing.

In my own bankruptcy I just followed along and never really knew what was happening for two reasons: (1) my brains were scrambled after Hurricane Katrina and my financial collapse, and (2) I let my lawyer “make it easy” for me and just followed along without studying the game and figuring out how to win. I had options, lots of options that were never presented to me, and I never went and unearthed them on my own. So, here's who's showing up:

- Debtor in Possession (DIP). This is current ownership/management – you if you are the entrepreneur. In the first instance, the debtor acts as his or her own trustee and has relative control over the case. Prepetition management stays in possession (control) of the business. They have first crack at a turnaround plan and 120 days to present it to the court. Sometimes this is a good thing, and sometimes management is the problem.

- Secured Creditors. Secured creditors are usually a bank or other prepetition lenders. They have security interest (liens) on the assets (collateral) of the business along with, likely, personal guarantees of the majority owners. Even the third or fourth lender to a business is likely to have filed liens and have a secured claim. You will generally have to make arrangements to pay secured creditors some amount during the case, especially if they are oversecured.

- Unsecured Creditors Committee. This is a representative leadership group of vendors and other trade type creditors who have no direct liens on assets. While trade creditors often make up this committee, it can also contain bondholders and tort claims. The committee is appointed by the U.S. Trustee's Office to represent the collective interests of the unsecured creditors. The opinions of the committee generally carry a lot of weight with the bankruptcy judge, and the committee, surprisingly, can be constituted of your adversaries who pushed you into the Chapter 11 corner.

- Equity Holders Committee. The shareholders of the business. If there is a wide ownership structure, then they may elect a committee to represent their joint interests. If ownership is just a few people, they will not need a committee.

- Ad Hoc Committees. These committees are anyone else who feels they need a voice. Common examples are bond holders, shareholders, tort, future claimants, and junior debt.

- Parties to Executory Contracts and Unexpired Leases. An executory contract is one in which the terms are to be completed at a future date, so it is largely an unperformed contract, though with real damages under a breach. Leases work in a similar fashion and are often the crux issue in a retail bankruptcy. To “assume” a lease in Chapter 11, you must first cure it by paying all amounts due prepetition.

- The Examiner. This is a professional appointed by the bankruptcy court to investigate and report the activities of the business to the court. These are only appointed as a fall back and with cause. In the first instance, the debtor controls the ship. In a filing that is surrounded by accusations of fraud, an examiner will be given specific instructions to investigate all irregularities and possible solutions.

- Chapter 11 Trustee. Like an examiner, a

Chapter 11 trustee only comes on the scene when the debtor has

fallen down on the job. This person is appointed by

the U.S. Trustee Program to administer the

bankruptcy. They gather, manage, liquidate, and account for the

assets of the debtor while paying bills and administering the costs

of the bankruptcy. They are infrequently used in Chapter 11

filings. Trustees have a financial incentive, called the trustee

commission to collect on and liquidate assets for the creditors.

The current formula is a sliding scale that rewards the trustee for

his or her work:

- 25% of the first $5,000;

- 10% of the next $45,000;

- 5% of the next $950,000; and

- 3% of the balance.

A debtor can often feel held hostage by this incentive and many feel they have been unfairly squeezed out of protected assets when given the option of settling or the long, painful grind of being investigated by the Bankruptcy Trustee.

- The U.S. Trustee. The United States Trustee's Office is part of the U.S. Department of Justice. The office is separate from the court and a watchdog agency charged with monitoring bankruptcy cases, identifying fraud, and supervising all trustees. They take a more active role when no creditors' committee has been appointed – they fall into the role of protecting unsecured creditors. The U.S. Trustee's office will review all petitions and pleadings in the case and participate in some proceedings. The U.S. Trustee's office can file motions to dismiss the case (awful for the debtor) or to convert a case from, say, a Chapter 11 reorganization to a Chapter 7 liquidation (game over). The U.S. Trustee's office charges quarterly fees to the estate during the course of the bankruptcy.

- The Bankruptcy Court. The bankruptcy courts are subject matter jurisdiction units of federal district courts, which have original and exclusive jurisdiction over all bankruptcy cases. Most proceedings are held before a U.S. bankruptcy judge who serves a 14‐year term after appointment by the U.S. Court of Appeals in that circuit. Judges typically don't take active roles in cases, but only respond to filings made by these various constituents. One judge likened their role to being in a closet at a party – you have an idea of what's happening, but only get a clear picture when someone opens to the door to ask you to resolve a dispute.

- Powerful Government Agencies. This includes; IRS, EPA, DOL who will not be deterred by your bankruptcy filing. Generally, don't mess with wages, payroll taxes, retirement trust funds, or environmental issues. They will follow you right into court and, surprise, these federal agencies have a loud voice in this federal court.

When you review the list of players one thought should sink in; you are completely outgunned, which is why you need an excellent bankruptcy attorney and a path, and why you need to be entirely tuned in to the process.

The Professional Team

People wonder why bankruptcy costs are so high? Here's why.

- Lawyers, lots of lawyers. Your regular old commercial lawyer and his litigation partner is going to tag along while you pay a corporate bankruptcy lawyer top dollar. Like a cardiologist, these guys are billing at the top of the food chain, regardless of location. Bankruptcy attorneys work feverishly to prepare a filing and administer it through the early exciting and contentious days of a filing.

- “Ordinary course” professionals. You still need your CPA, your tax attorney, and maybe your outsourced CFO.

- Valuation experts. As you'll see, the successful way out of bankruptcy is driven by the valuation of the business. You'll have your experts, the creditors will have theirs, and then the lawyers and valuation experts will argue about who is right – all on the company's dime. It's easy to have 10 high‐dollar professionals debating for hours the value of the business, but the final path forward will be set in these discussions, so it is critically important.

- Accountants. There are lots and lots of accountants auditing backward and forward to make sure everything is pinned down and explained. The bankruptcy process is driven by the transparency of accurate numbers, so accountants are at the core of it all.

- Financial advisors. In larger cases, financial advisors might be a firm that specializes in restructuring bonds or commercial debts. In businesses under $50 million, you might have one consultant doing the restructuring, selling, and fixing of the business all at the same time.

- Investment bankers. Perhaps we've entered a Chapter 11 intending to sell the business through a 363 bankruptcy sale process. We'll need sell‐side advisors with experience marketing distressed business through quick and efficient bidding.

- Turnaround consultants. Turnaround consultants are the professionals managing the cash flow and daily operations of the business, while also crafting and executing the turnaround and restructuring plan to fix the business and set it up for long‐term future success.

- Auctioneers. One of the first auctions I ever managed had a used Toyota pickup truck that everyone blue book valued at $16,000. The auctioneer opened bidding at $14,000 to pull people in. No one bid. He dropped to $13,500 – nothing. $13,000 – nothing. $10,000 – nothing. He dropped down all the way to $3,000 before capturing the first bid. Then slowly, incrementally he brought in others and created momentum. The bids were gathering steam as they roared passed the initial opening value of $14,000 and past the blue book value of $16,000. The maestro whipped the bidders into a glorious overvalued crescendo peaking with the final bid at $17,700. For thousands of years, auctions have been the most efficient and effective way of deriving full value from assets in a completely public and transparent manner. Auctioneers are also appraisers and help creditors establish a worst‐case liquidation value.

Funding a Bankruptcy

Bankruptcies are funded either by cash reserves, internally generated cash flow, cash infusion, or from loans. A company that can internally fund a bankruptcy likely has a strong income statement and an overburdened balance sheet. The purpose of this filing would be to haircut the debt and give this well‐performing business a right‐sized balance sheet. Companies for which both the income statement and balance sheet need repair are harder to save, and the law only gives you 120 days to create a good plan, with some exceptions. Before filing, you must ensure that if you put aside legacy debt, the business will cash flow. If not, don't waste your time. Additionally, you've got to finance this period of time while paying absurd professional fees.

Loans are possible and they are called debtor in possession (DIP) loans. They enter the debt stack at superpriority position, above all other creditors provided the secured creditors agree to be subordinated. It seems like a pretty big ask for management to tell creditors: “We obviously screwed up but we're going to subordinate you so we can take on even more debt and we've got 120 days to come up with a plan.” But the courts allow it because, like the railroad, the possibility of a going concern has the greatest value to all stakeholders. Likewise, the incumbent senior secured lender is free to offer that DIP loan if they wish to increase their position. Another interesting tension in bankruptcies is that creditors may safely recover their value through a liquidation, whereas equity holders must pursue risk to recover their value.

It would be hard and rare for a business with revenues under $50 million to attract a DIP lender. Below that volume, a business without positive cash flow or significant cash reserves is unlikely to survive a bankruptcy. They will struggle to secure financing, and the base costs of a filing will be disproportionally high to their revenue base. A company that enters weak can be converted to a liquidation by an aggressive creditor. Bigger filings with very secure assets (say a critical parts supplier to Boeing) will attract banks and bank type lenders who simply want a fair return on conservative risk. Filings with less secure assets, like a consumer brand company, will attract “sharkier” type investors including loan‐to‐own investors who simply want an outsized return for their higher degree of risk and/or to wrestle control of the company away from the owners.

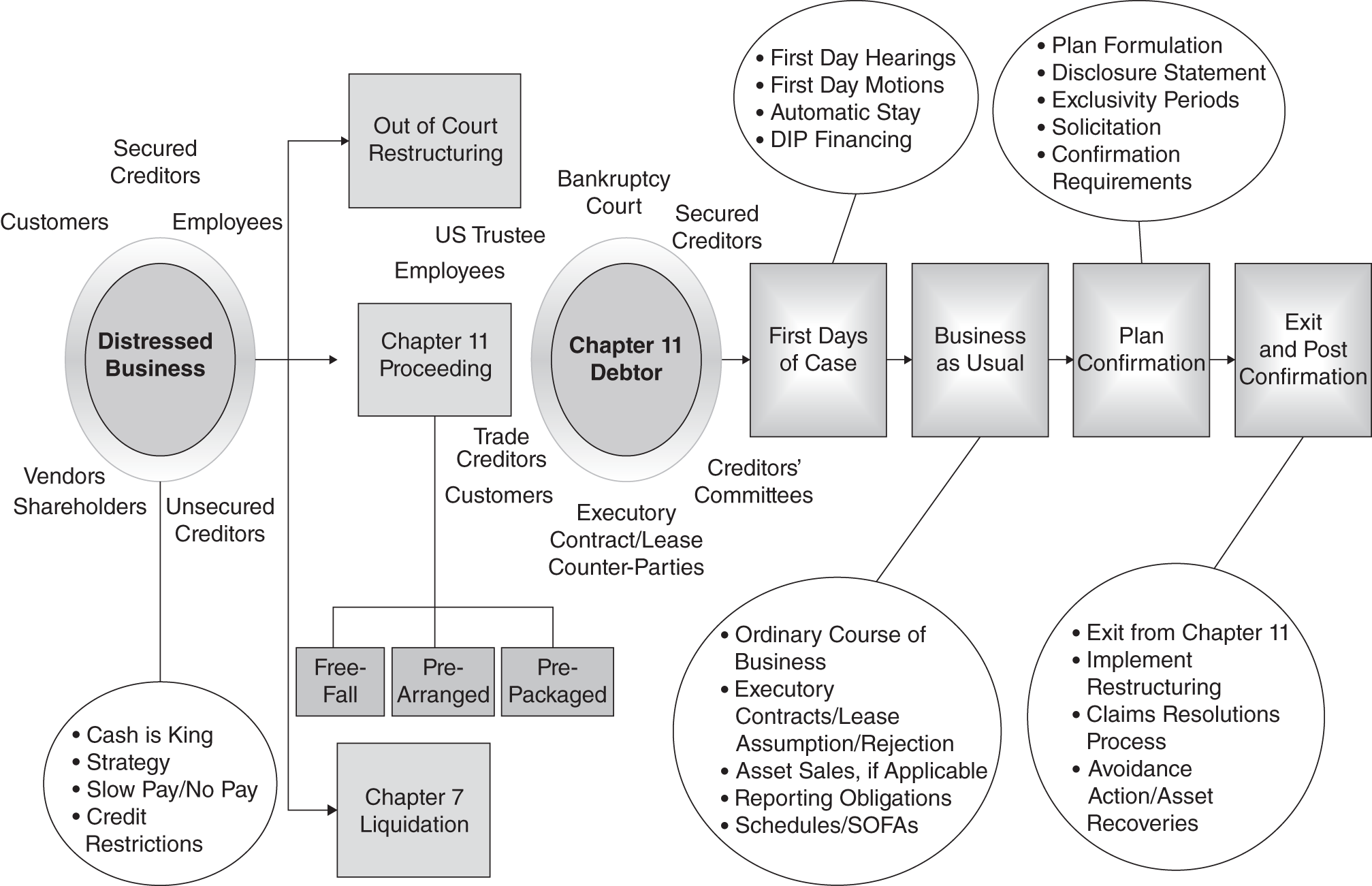

Bankruptcy is a safe harbor for beleaguered businesses. A company can file a Chapter 11, get immediate relief from creditors, and have time to formulate a plan and marshal resources before facing up to its debts. Figure 7.3 illustrates the restructuring options facing a troubled business along with the Chapter 11 process.

Activities in bankruptcy proceedings are particularly intense at the start and end of the process, whereas the many months in between are focused primarily on running the company and administering the bankruptcy. If you're lucky, it is all quite mundane. This has been referred to as an inverted bell curve of activity, something I refer to as the Valley of the Grind.

Figure 7.3 The bankruptcy process.

Credit: James H.M. Sprayregen and Jonathan Friedland

Stages of a Bankruptcy Filing

The first stage of a bankruptcy filing is strategy and preparation. A good attorney won't let you file without a really good plan of what you want to accomplish with a filing. Bankruptcy is an expensive and dangerous tool that should only be handled with great forethought and planning. As we lay out the objectives of a filing, perhaps there are ways to accomplish the same results but out of court. Even until the day of filing, your options are open. A negotiation with your largest creditor, in which you bring and place your completely filled out bankruptcy schedules and petitions in the middle of the table, may break a prior impasse.

Stage 2 is the actual filing, which always generates great amounts of excitement as the debtor files a raft of schedules and “first‐day” motions, which reveal the heretofore darkest secrets of its finances and operations. Often, these papers hint at the ultimate plan of reorganization, but in many instances, that is not revealed until much later. The company is now in play, and this is when the tables turn for everyone involved. If news of your intentions were to leak out before the filing, vendors could shut off supply, or banks may offset accounts and inflict harm upon the business or customers, or critical employees could get spooked and leave. A company normally files in their state of incorporation, which is immediately part of the public record and picked up on news feeds. However, unlike filing choices in business litigation, a debtor can file in any jurisdiction in which it does business, giving the filer broad opportunity to forum or judge shop. Most big cases end up in Delaware or New York, both of which have extensive and predictable bodies of case law. Every single creditor will be listed on schedules, and they will immediately begin receiving notices from the bankruptcy court advising them of the filing. To receive anything beyond the original filing, however, one must file an “appearance” in the case and should do so immediately. When the secret is finally released, the news will ripple through all levels of the community. Your employees will be shocked, and the bank may be caught off‐guard by a filing. Communities in which your suppliers live may will be affected. As an entrepreneur, the searing light of transparency will shine on you, but if you are a crafty capitalist, this may all be part of a well‐orchestrated business strategy.

Filings are made online these days, and the file is time stamped when received by the court. All debt incurred before that moment is now suspended and will be administered through this process. An automatic stay is statutorily imposed by the bankruptcy code, as the name implies, automatically. This means that all creditors must immediately stop all collection, foreclosure, and eviction activities. Even if they were in the process of repossessing your delivery trucks, they have to stop or revert back to that very minute when the filing was made. Even government agencies, with some exceptions, must stop and adhere to the rules of bankruptcy. This includes IRS collection efforts but does not include police powers of arrest or, perhaps, EPA‐type enforcement.

With the filing comes the first‐day motions in which the company petitions the court for things like:

- The ability to pay prepetition employee wages, because no one wants employees upset when trying to maintain value in the business. Prepetition and prefiling mean the same thing.

- The ability to maintain current bank accounts and cash‐management procedures.

- The ability to use the cash collateral in the business to fund ongoing operations.

- The ability to hire attorneys and other insolvency professionals.

- Perhaps the ability to pay certain critical vendors some or all of their prepetition debt.

These are often approved temporarily on an ex‐parte basis (with only a limited hearing). Motions approved by the court become first‐day orders, which allow management some flexibility within the statutory prohibitions of the bankruptcy code. The debtor group is expected to attend hearings on the first‐day motions while also communicating with employees, customers, creditors, investors, and maybe even the press. The debtor will also meet with the office of the U.S. Trustee and prepare exhaustive schedules for the court.

In these initial days, the U.S. Trustee will attempt to form a creditor's committee and possibly other committees with wide ability to watch over the debtor business and participate in the forming of the reorganization plan. With court approval, the creditor's committee may hire an attorney and other professionals. This is the debtor's time to shine. The more convincing management can be that they have a good plan, the more support they will receive. Committees are generally not the friend of the debtor, and to some extent they can be avoided through communication with these constituents prior to or immediately after the case is filed. If parties trust you, they'll give you some rope to run things – for a time.

The third phase of a bankruptcy case is the long middle part where the business runs in a somewhat ordinary course of business. Vendors are paid promptly, shipments are made, employees are paid, and so on. There will continue to be deadlines and required filings and an occasional dust up as creditors comment on past or present management decisions. If creditors don't like how the company is managed in the turnaround, they can petition the court with their suggestions. If they feel certain parties were unfairly paid in the months leading up to the filing, creditors can request the debtor to seek avoidance of prior payments and “clawback” or “disgorge” those funds back to the estate. This means undoing the transfer through force of the court. The debtor is motivated to accumulate the greatest possible pool of assets for the benefit of its reorganization efforts.

Payments or transfers are usually avoided (reversed and recovered) for one of three reasons:

- Fraudulent transfer, like selling company assets really cheap to your brother in the months or even years leading up to a filing. The court will force him to return those goods at their value and it will be an unpleasant experience for him to do so. There is a two year look‐back period under bankruptcy law for such transfers, and in some states this period is up to four years.

- Preference. The court assumes the

debtor was considering bankruptcy for 90 days before the actual

filing and may have made moves to advantage certain creditors over

others and in direct contradiction to the absolute priority of debt

rules. The court expects to see that creditors were paid in an even

way over the months preceding a filing. If one or two creditors

were paid outsized amounts, then those payments will be

investigated. If, say, the payment was COD for steel to supply an

extraordinarily large shipment, then that is a “normal course”

transaction and may not be avoided. If vendor payables are all

stretched an average of 60 days but one gets paid off in full,

leading up to the filing, well that smells fishy and will likely be

“avoided.” Meaning the court will force the vendor to return those

payments.

It's the timing and amount of payment that stands out, not so much the legitimacy of it during insolvency. If payments are standard and part of the business operations over a long period of time, then they will be considered “ordinary course” and not extraordinary. I know a situation in which the entrepreneur was having the company pay $10,000 per month for years into the (bankruptcy exempt) cash value of his life insurance policy. When hard times came and the bank scrutinized expenses, this was never objected to, likely because it was buried in the Insurance line on the income statement. The company eventually failed and filed Chapter 7, but those payments were made right up until the actual wind‐down, allowing the 100% founder/owner to keep all that cash value.

- Strong‐arm powers (actual name). This clause gives the trustee special powers to “avoid” (get rid of) certain liens and unperfected security interests. Assets like real estate or big mills may have unperfected mechanics liens. Or the company borrowed from a wealthy uncle and the loan agreement clearly states a second lien on named assets but the wealthy uncle's attorney forgot to file the proper paperwork to register that lien. These are creditors who do not have a voice at the table and whom the debtor or a trustee can just wipe out to clear the deck for the creditors who do have supportable claims.

Early in the middle period of the case, the debtor will be required to attend a first meeting of creditors in which the debtor company's representative will answer questions to the U.S. Trustee and perhaps creditors under oath. The debtor will also have to meet in private with the U.S. Trustee in what's called an initial debtor interview where the U.S. Trustee's financial analyst will inquire about the inner financial workings of the business and the anticipated plan. Creditors then begin submitting proofs of claim, which may later be allowed or opposed by the debtor.

This long middle path is overrun with distractions, which can easily get a CEO unfocused on the goal of successfully exiting the company from bankruptcy. A real danger during this period is a lack of change, and it is incumbent on the debtor's professionals and other constituents to ensure it's not just business as usual – real restructuring needs to occur. Segregation of duties is the best way forward. The CEO should be head‐down focused on the business while professionals deal with the sorted administrative and legal encumbrances encountered along the way.

Phase 4 is the exit from bankruptcy. This requires a plan that creditors vote on and must be approved by the court. As we'll see in Chapter 8, Debt Restructuring, bankruptcy is little more than a big complicated way of negotiating your debts with creditors, with referees. The company has to offer everyone a good enough deal based on the fundamental recovery power of the business. While out of court, angry creditors can refuse a good deal and continue to harass you; in bankruptcy they need to sit still until they either agree to a deal or one is “crammed down” upon them by a majority vote of creditors. Each creditor class is resolved by majority acceptance of the plan (>50% in number and >two‐thirds in the dollar amount of claims) and all creditor classes need to be either made whole or resolved before the plan can be confirmed and the company is released from bankruptcy.

Prepackaged bankruptcies are becoming more and more common, especially among more experienced filers. Also referred to as free fall, pre‐arranged, or prepack, these are bankruptcy filings that have been so thoroughly orchestrated that the creditors are already on board and support management in the plan. This way the filing sails through the process and, in theory, gets a quick confirmation of plan and release on the other side. On the surface, getting your creditors to all accept a haircut without the hammer of bankruptcy seems like a really tough task but often they are highly motivated to see the company survive. Here are three situations I can think of offhand in which a prepack might make sense:

- If I'm a turnaround investor and I find a

business with the following maladies: the supply chain is locking

up, customer orders are late, the company supplies critical

limited‐supply parts or services to big companies, and the problems

seem fixable. Without help, the current path will lead to some

critical vendor cutting them off, which will create a domino effect

resulting in an unfunded payroll and the total collapse of the

business within weeks to months. This is the equivalent of a vendor

repossessing his two miles of railroad track. I might be clever

enough to gather the customers, vendors, and employees together and

paint a better picture – one in which we all hold hands and save

the business for the benefit of all. You can liquidate the meager

assets now and maybe the only one who gets paid is the bank; vendor

debt gets completely hosed, employees lose their jobs, and

customers have big issues without supply. But if we support the

company, the bank can remain protected while vendors can receive

partial payments from future cash flows and customers and employees

are very happy. We all agree and formalize it through an expedited

(prepack) Chapter 11. This provides the cleanest possible (most legally certain) way of transferring in

assets and locks in commitments.

This sort of prepack sale of substantially all the assets happens under section 363 of the bankruptcy code. Today many Chapter 11s are filed with the goal of simply selling the assets through an expedited auction process where a bidder agrees to allow his offer to be bid against – known as a stalking horse bidder. The stalking horse bidder is afforded certain financial remuneration if he is outbid. Generally, the sale price has to cover the level of secured debt only, and the buyer will take the assets free and clear of any and all claims, including unfavorable worker's compensation mod rates. Often, 363 sales are entirely engineered prior to the filing, then quickly approved by the Court. Frequently, all that's left is the bidding.

- Think of the GM or Chrysler bankruptcies; those were largely precoordinated and set records both for size and speed of plan confirmation. Over time, Chapter 11s had grown lengthy, cumbersome, and expensive. By the mid‐2000s it was not unusual for a Chapter 11 to take 18 months and need to fund preposterously high professional fees. In 2009–2010 a postfinancial crisis wave of bankruptcies hit the courts and overwhelmed them. The courts applied direct pressure to attorneys and have both cut attorney billing rates and sped up the process considerably. GM and Chrysler are prime examples.

- Asbestos claims have driven many companies through an arranged bankruptcy even if it wasn't done in the modern prepack fashion. When a healthy company gets hit with a massive lawsuit (unsecured claim), it can suddenly owe an amount that defies math but makes sense only to a jury or government regulator. This can be seen as an attack on all the stakeholders of a business – owners, customers, vendors, and employees – which makes unifying their defense much easier.

Plan of Reorganization: Six‐Step Process

- Negotiating the plan with major constituencies.

- Drafting the plan of reorganization and the disclosure statement.

- Getting court approval for the disclosure statement.

- Solicitation process with creditors who are “impaired” or not made whole through the reorganization.

- Confirmation hearing.

- Performing to the plan.

You'll see that this requires a bit of shuttle diplomacy. The debtor must get stakeholder consent for a plan, then build out that plan, then get the court to approve the plan, then get the stakeholders to vote on the plan, and then get the court to confirm that vote.

All this starts with a well‐defined exit plan, which is developed by the debtor within the 120‐day exclusivity period. If the debtor fails to develop a successful plan (or get the court to grant extensions, which it prefers to do less of these days), then other parties can suggest plans. This is a distinct debtor advantage to the U.S. bankruptcy system because the debtor has plentiful opportunity to control the process.

The plan of reorganization should ideally detail structural and management changes to the business and then forecast the impact of those changes through the standard financial statements. The plan will also show the balance sheet impact of: asset sales, divestitures, shutting down divisions, debt to equity conversions or reverse, equity issuance or cancellation, restructuring debts through principle, amortization, and/or interest rate, as well as all the attendant legal matters such as adjustments to liens, curing or waiving defaults, and changes in corporate governance or structure.

Think of the disclosure statement as being similar to the details buried in the prospectus of a financial investment package. In effect, you are offering debts and equity in a renovated company for a prescribed amount of money. Interestingly, you will not need to comply with Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulations that might cover this sort of offering because bankruptcy is a safe‐harbor from SEC‐type rules. It's not unusual for a disclosure statement to exceed 50 pages as it reestablishes all creditor claims and classes plus assets. The plan meticulously describes how each piece or class of collateral will be used to satisfy the claims upon them, detailing the percentage net recovery for each creditor or creditor class. The statement will cover voting rules, risk factors, feasibility, liquidation analysis, tax consequences, and perhaps even multiple payout options for the plan. Once prepared, the plan and disclosure statement are submitted to the court for its approval.

Like everything else in life, the entire bankruptcy restructuring process requires salesmanship. The debtors and their professionals will need to persuade each creditor or creditor class (and their professionals) that this is the best possible recovery from a crummy situation and earn their support while the plan is being constructed. The debtors will need to carry that support through the process and manage their creditors who may want to lash out at the debtor. If a class of creditors is paid in full, then those creditors are satisfied and there is no need for them to vote. However, if the creditors are required to restructure their debt in any little way, then they are “impaired” and thus entitled to vote, ideally in favor of the plan. It is only impaired (not fully satisfied) classes who get to vote their approval of the plan. For approval, a creditor class needs support of a majority by number of creditors in that class and two‐thirds support of the creditor dollars owed. There is the possibility that a creditor class will refuse the debtor's offer and seek to hold up the entire exit. Without a better alternative, the court may “cram‐down” or force the dissenting creditors to accept the offer on the grounds that other creditor classes have, and the solution is seen as better than a Chapter 7 liquidation. This is why you'll often see trade creditors receive maybe 10% recovery even though, mathematically, they should have been out of the money. The 10% may be an offering from the senior creditors as the juniors are forced/persuaded to accept the plan. Again, it all comes down to the strength of the reorganization plan. It is required to exit a bankruptcy, and the court will often go out of its way to protect a good plan, because they are a rare and valuable thing when every other option is carnage.

A successful restructuring offers what no other insolvency outcome does – namely, the prospect of future cash flows. So while a liquidation feeds a few quickly (and destroys a community), a reorganization feeds many slowly and protects economic vitality. With future cash flows, low‐ranking creditors can be paid out over time, and the family loan can be converted to equity and benefit through their continued support of the business.

The following pro forma income statement (Figure 7.4) shows a company which declined in 2017 and filed Chapter 11 later in that year. With support from creditors and customers, the business can restructure its debts, stretching some out while haircutting others, cut costs, and reenergize the business. This creates future cash flows to service the ongoing debts and provide long‐term value to all stakeholders.

| Income Statement | 2016 | 2017 TTM | Forecast 2018 | Forecast 2019 | Forecast 2020 | Forecast 2021 | Forecast 2022 |

| Revenues | 10,000 | 8,000 | 9,000 | 9,500 | 10,000 | 10,500 | 11,000 |

| COGS | 6,500 | 5,600 | 5,850 | 6,175 | 6,500 | 6,825 | 7,150 |

| GPM $ | 3,500 | 2,400 | 3,150 | 3,325 | 3,500 | 3,675 | 3,850 |

| GPM % | 35.0% | 30.0% | 35.0% | 35.0% | 35.0% | 35.0% | 35.0% |

| SGA | 3,500 | 3,500 | 3,000 | 3,000 | 3,000 | 3,000 | 3,000 |

| Operating Profit (cash) |

– | (1,100) | 150 | 325 | 500 | 675 | 850 |

| Debt Service | 500 | 500 | 50 | 100 | 150 | 175 | 200 |

| Net Cash | (500) | (1,600) | 100 | 225 | 350 | 500 | 650 |

| Cumulative Cash Recovery | – | 225 | 575 | 1,075 | 1,725 |

Figure 7.4 Pro forma income statement showing future cash flows for servicing debt and building equity.

Future cash flows are not balance sheet items, meaning they can only service debt if the business can be made profitable. That is why a successful restructuring, no matter how deep the losses are, is usually preferred over a liquidation. Figure 7.5 represents these future cash flows and shows a significantly higher recovery in a successful Chapter 11 reorganization compared to a Chapter 7 liquidation. In this situation, two more classes of creditors receive a full recovery, a third class receives a partial recovery, and the family loan is converted to equity. Not illustrated are the cash‐flow benefits from stretching out the company's debts.

With votes solicited, the debtor goes back to the court for confirmation of its plan based on satisfying the following 14 requirements:

- The plan and plan proponent are both in compliance with the Bankruptcy Code.

- The plan was developed in good faith.*

- Bankruptcy Court approves the accrued payments to professionals.

- The plan provides full disclosure and identity of postconfirmation officers and directors.*

- Regulatory approval if

required.

ACME Mfg. – Value Preservation in a Reorganization Account Book Value Chapter 7 Liquidation Chapter 11 Recovery Cash – – – Accounts Receivable 1,000 800 900 Inventory 2,500 625 1,800 Total Current Assets 3,500 1,425 2,700 Machinery and Equipment (net) 1,800 1,200 1,200 Intellectual Property 500 20 100 Furniture and Fixtures 200 – 40 Computers and Software (net) 700 10 140 Leasehold Improvements (net) 800 – – Goodwill (net) 1,300 – Bankruptcy Admin Fees (200) (500) Value of Future Cash Flows 1,725 Total Long‐Term Assets 5,300 1,030 2,705 Total Assets 8,800 2,455 5,405 Recoveries in Priority Rank First Bank Revolver 2,100 2,100 2,100 First Bank Term Note, SBA backed 1,500 355 1,500 Second Bank – Cash Advance Loan 250 250 State BDC Loan, no PG 100 100 Family Loan 1,000 Accounts Payable 1,500 1,200 Total Recoveries 6,450 2,655 5,150 Recovery 38% 80% Equity 2,350 0 255 Figure 7.5 Improvement in creditor recovery through a successful reorganization.

- Best interest of creditors test, which requires a result better than liquidation. Otherwise, a liquidation is in the best interest of creditors.

- The plan is consensual.

- The plan provides specific treatment of administrative and priority claims.

- Prohibition on complete “cram‐down” plans, there needs to be some levels of support.

- Feasibility.*

- Payment of court, filing, and US Trustee fees.

- The plan protects retiree benefits.

- The plan treats transfers to not‐for‐profit entities properly.

- The plan and the filing are not simply a ruse to avoid taxes.

With the necessary votes of creditors and confirmation by the court, the company exits bankruptcy court with a clean slate. Although there may be some emotional overhang, there is no/none/zero trailing liability exposure. Short of fraud, it is impossible for a bankruptcy process to be unwound or revisited. It is legally impenetrable, which provides the greatest possible comfort to participants and is part of bankruptcy's appeal.

The Stigma of Bankruptcy

Years ago, when I was contemplating my own bankruptcy, an attorney in New Orleans told me that in certain industries bankruptcy can be seen as a badge of honor. In a slow southern drawl he said, “Hell, in the oil business if you don't have at least one bankruptcy under your belt people won't think you've been trying very hard.”

Although I don't know the individual backstories, here is a list of famous people who have filed for bankruptcy protection: Abraham Lincoln, Charles Goodyear (tires), Daniel Defoe (Robinson Crusoe), George Fredric Handel (composer), Henry Ford, James Wilson (Supreme Court Justice), Milton Hershey, Oscar Wilde, Oskar Schindler (Schindler's List), Rembrandt, Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), Thomas Paine, Ulysses S. Grant, Walt Disney, William McKinley (25th president), and Donald Trump (45th American president).1

Well‐known companies that have survived through bankruptcy include General Motors, Chrysler, Dunkin Donuts, Samsonite, Mrs. Fields, the Chicago Cubs, Gibson Guitars, Pacific Gas & Electric, Delta Airlines, American Airlines, United Airlines, US Airways, Air Canada, and many others.

When Should You Throw in the Towel?

It is rarely clear how long you should fight to stave off bankruptcy or when you should just give in and focus on recovery. Logically, giving in might be the best option, but accepting failure and moving on has a high emotional cost that can stay with you for years.

Emotional Argument – Never file bankruptcy; the regret will tear you up and eat you alive. I've given this speech to clients but I believe it in my soul; I would rather be Cool Hand Luke standing back up to get knocked down again and again than to live with the years of regret. I would torch the whole village – dogs, cats, children – to avoid going through that again. I did it totally wrong and ended up on the very short end of the stick, and the regret has been a burden to bear. I wouldn't recommend bankruptcy to anyone.

Financial Argument – A reasonable rule of thumb that if you can't conceivably pay off your extraordinary debts in five years, then you should consider a bankruptcy filing. It's a reasonable measure, and bankruptcy does give you the certainty of release and a clean slate. There is also some satisfaction of flipping the bird to certain creditors as you grit your teeth and file. You'll drag that clean slate of bankruptcy around like an anchor for 10 years while it's on your credit report, but most of those issues can be solved with creativity. This financial argument also denies the possibility of restructuring your debts out of court, which is usually possible. Every so often, even a logical restructuring is impossible because your creditor simply wants to push you off a cliff. If that's the case and you're trapped with no way out, then you simply need to switch to defense, re‐arrange your assets (legally), put on your helmet, file the bankruptcy and take the hits.

Reorganization Out of Court

I once had an investment banker tell me that he had referred three distressed clients to bankruptcy attorneys and each time the client ended up filing bankruptcy. “And now,” he said, “I'm wondering if that's just what bankruptcy attorneys do? Like the hammer who sees every problem as a nail?” For some attorneys the answer is yes, they are one‐trick ponies. For an entrepreneur, I suggest an attorney with both legitimate bankruptcy and litigation experience, someone who can fairly advise you of your full range of options, both in and out of court. Also check their backstory as it may reveal character and drive. One excellent bankruptcy attorney in upstate New York experienced her parents' bankruptcy as a child and she is a bit of a caped‐crusader, trying to protect others from similar loss. A good friend, who has become a federal bankruptcy judge, had his own entrepreneurial roller coaster ride with his family‐owned restaurant. After a few years of ups and downs, they sold the restaurant, and, although it didn't make him wealthy, it certainly made him a better bankruptcy attorney and judge.

Everything we just covered in this chapter provides the backstop against what you negotiate out‐of‐court settlements with. Said another way, bankruptcy is the anvil against which out‐of‐court settlements are established and what we cover in the following chapter.

Note

- *Most likely points of contention between debtor and creditor.

- 1. http://www.bankruptcylawhelp.com/Bankruptcy/Famous-People-Who-Filed-Bankruptcy.aspx.