Chapter 5

Turnaround Management

With a reprieve from the bank (however nominal it may feel), you now have to fix the underlying business. I call this patching the holes in the bottom of the boat. The analogy I paint for clients is that if this business were a boat we'd have a $100 million boat with $100 million worth of holes in the bottom of the boat. What we must do is find the biggest holes and make them smaller. “Think about it,” I say, “You've got $100 million of other people's money passing through your hands every single year and you haven't figured out how to keep any of it.” That's the whole problem. It's not revenue; it's you being at the bottom of the food chain. You have all the risk but you're the one who's not getting paid. Everyone else has been paid well for years except you.

To find our way out of this problem, what we fix first is the business model. If we're losing money, then our model is broken, simple as that. Do we have competitors who are profitable? What's better about them than us? Are they charging more, servicing better, have economies of scale, better customers, do they pay less, are they shrewder, what do they have that we don't? That's the difference. If we have five competitors and three are making money and two doing okay, then what's unique about them? How do they make money? We can also consider our past to see if the business had ever been profitable. When was that and what's different now? If a company has a historical profit that it can point to, then the odds of a turnaround are high. Even with sales sawed in half, there is probably a fundamental model that works and some muscle memory that can take us back there. If we can get our percentages of revenue to match for each cost category, then why can't we restructure the business like that? This is the land of 1,000 questions. Our only hope of saving this business is fixing the model. Sometimes it's easy and obvious; other times it is harder than a Rubik's Cube.

If the company has never been profitable, then the odds of turnaround success are very low. We have no historical demarcations; the company has always been adrift in the sea of losses never once finding safe harbor. Who knows where we should drive this ship from here? We'll model toward our successful competitors, but it's all on guesswork. Can we successfully get to a place the company has never been before and build cash in the process? It's very unlikely.

Most turnarounds involve businesses that are only about 30% broken and it's usually the entrepreneur's Achilles tendon. You'll get an engineer who forgot about sales, a salesman who didn't pay attention to accounting, or an administrator who forgot about service. Figuring out what's not working in the biggest ways is how we patch or shrink those holes in the bottom of our boat.

Each turnaround company is dysfunctional in its own special way, but they often follow a storyline. Here's a sampling of broken business models and solutions:

- Three trucking companies. They lacked

courage on pricing and invested their thin margins into geographic

expansion while driving their fleet into the ground. Drivers were

leaving to drive better equipment for competitors. Price increases

and cutting the least profitable lanes provided the solution.

- Four machining and fabricating companies. All four were running on thin gross margins with a lean backlog, which led to periods of starvation when the order book ran dry. The solution was an investment in sales, quoting, and estimating – all with the goal to quote twice as much business with an additional 10 percentage points of gross profit margin. This was to net about the same topline revenue with a much healthier gross margin. We were aggressively raising prices and accepted a significantly lower hit rate; therefore, we needed to quote twice as much work to net the same monthly volume. Then we could quote more aggressively to fill in the lean months, giving us balanced and predictable profits. With steadier work and better margins, we were able to upgrade the team, which created a virtuous cycle of retained earnings.

- Retailers and distributors with stale inventory and no cash to refresh. This is easy: we shrink footprint (locations or square footage) and remerchandise, then have a big clearance sale and reinvest that cash into new and better merchandised inventory.

- A few companies with a brilliant yet self‐destructive entrepreneur owner. Each company had exceptional engineering, superior products, and good service but no cash and a broken supply chain. The products were priced right, but the cash was fueling the entrepreneur's vanity. When the entrepreneurs are the problem, either they respond well to electric shock therapy from the lender or they lose control of the business. Often, these misfit entrepreneurs have their companies sold in a foreclosure sale, and the most talented, least flawed can find employment with the new owner. Sometimes it works really well; the former entrepreneur enjoys the ability to focus in on his strengths without the risk or headaches of being an entrepreneur.

- In a chain of sports bars, the cash ($500,000/year) was fueling the entrepreneur's gambling and pill habit. I audited that business repeatedly, backward and forward, and just couldn't figure out where the money was going. My frustration was so palpable that the owner's wife whispered in my ear about her husband's vices. We had a big and uncomfortable intervention. Each of us drew our lines in the sand: he wasn't ready for rehab, she wasn't ready to leave him, and I was ready to go home and see my family, so I did.

- A manufacturing business with a lot of demanding and high‐maintenance distributors whose service and aggravation expenses were costing the company money and focus. There were about a thousand of these distributors, so we rated every single one on contribution margin and aggravation. The bottom‐ranked 25% were sent a pleasant letter retracting our agreement and wishing them well in future endeavors.

The bottom line is that a turnaround will be some formula of raising prices, cutting costs, streamlining operations, and fixing bad habits. Those are the internal management issues. Our job is to control them, and we will develop a thoughtful plan to improve them immediately and then permanently repair them over the next several months.

Gearing Up for the Battle

We've stabilized the crisis, but now the real work begins. We must deliver what we promised the bank. Again, take stock of your physical and mental health. How's your spouse handling it? How are you handling it?

Losses and bad habits have their own gravity and they naturally resist change, so we have to out‐think and out‐hustle our problems. This takes mental acuity, but most beleaguered entrepreneurs are not sleeping well. They are spending sleepless hours processing dread alone in the dark, next to their spouses but so alone. I lost months of sleep before learning some mental techniques to help me out. What the business needs is a mind change at the top. The owner needs to see everything through a new lens of understanding.

Few executives have ever thought of themselves as a chief profit officer but that's what the leader needs to be in a recovering company. Someone who wakes up every day to squeeze pennies out of the business, to provide greater stability, and all the societal rewards that come from a healthy business. As the most important part of a business, perhaps profits deserve their own executive?

Take an average industry. The top performers are making, say, 10% net operating profit, the middle performers (the C students) are making maybe 3% and the train wrecks are losing 5% annually. It's a 15‐point spread, and you can probably cost‐cut yourself half the way there. This is the slow grinding part of a turnaround. It's unglamorous and decidedly old‐school, but it works. Here's how we get from train wreck to mediocre; Professional purchasing can take two to five percentage points off the cost of goods sold with very little effort. Better scheduling can reduce direct labor another two to five points, plus there's one to two points in your indirect labor, one point wasted in your sales effort, and one wasted in administration. Costs are like fingernails – they must be trimmed continually. We're going to grind the operating costs down one basis point at a time, which is why you must be running the numbers on your business constantly. As an outsider, I am trying to quickly build a holistic understanding of the business by its numbers.

Mindset

I once counseled a beleaguered CEO about his people skills and encouraged him to act differently as we worked through our turnaround. The CEO still ran the 600+ person company like a fiefdom; it was him and 600 underlings. Managers didn't feel supported or communicated to and often felt like the CEO undermined them. These folks wanted to be on a winning team but didn't feel that team spirit coming from the CEO. I had lots of examples and carried on through my list while speaking with him. At the end, he calmly replied; “They had better get used to it.” After a pause, he continued; “My only goal in life right now is to save my business. I lose sleep over that, I don't lose sleep over how other people feel. I'll care about their feelings later, when we have a new bank.”

This CEO's opinion flew in the face of inclusive, kumbaya style pop‐management, but he was focused like a laser on saving his business and he did. He had a brilliant turnaround, saved most of the jobs, put lots of money back into the business, and five years later he lost the business, in part because of his poor management style.

Unions

The United Steel Workers union and I recently shared a prestigious Turnaround of the Year Award by teaming together to save an old Ohio steel fabricating mill. We shared an interest in saving the business, saving the jobs, and finding ways to make the business successful again. We have succeeded together and the union has been an exceptional partner over the past 18 months. I've shared similar success with other labor unions over the years and consider them vital partners in turnarounds.

But when a company flounders, the troubles often create the disruptive opening that union organizers look for. When profits and morale decline, this creates the opportunity for a union organizer to whisper sweet nothings in the ear of disgruntled workers. A regional trucking company I worked on endured two union‐organizing campaigns at the beginning of our turnaround. The bank had threatened liquidation, we had zero cash, and now our facilities, in two strong union towns (Buffalo and Newark), were turning against us. Their complaints were legitimate but driven by the company's poverty, not the malicious intent of the owners. We were caught flat‐footed and needed to respond, quickly. Phil, the owner, took the union support as a great personal insult and from his perspective it was. He was a man of the people, a trucker's trucker. Phil could out‐hustle anyone on the docks or on the road, and he radiated a charisma that naturally drew people to him. But, over the years, Phil had grown comfortable being home for dinner and parenting his kids. His lifestyle had remained modest but that's not how the union organizers spun it. “Have you seen Phil? No, I bet he doesn't visit you guys anymore now that he's bought a new mansion, and have you heard about his yacht? Oh boy!” All lies, of course, but for a prideful guy in Buffalo who's driving a beater truck with over one and a half million miles on it, and hasn't seen Phil in several years, you start to wonder, “Where is the money going?” The organizer whispers. “Not into your wages, not into equipment. I'll tell you where it's going: Boats, RVs, vacations, and his second wife”… blah, blah, blah.

Our plan was twofold; we would call our union specialist to help us navigate within the rules of the National Labor Relations Act. When the union buries us in phony grievances, the specialist helps us process through the bureaucracy and keep a positive message within guidelines that can feel like an Orwellian form of censorship. When equipment is sabotaged, and the local unionized police force refuses to respond, we stick to the business and make things better. The other part of our plan was to put Phil on the road. Fortunately for Phil, he has the charisma that can turn the tide. A day on the docks in Buffalo changed everything. There was Phil with his natural swagger and charisma, melting hostility before our eyes. He joked, teased, scolded, assisted, and out‐hustled everyone on the docks. We hit all three shifts, and our work was done. The union withdrew their organizing plans before being embarrassed by a vote.

One tremendously scrappy entrepreneur I worked with unionized his own shop. He was in the food business but brought in the local hospitality workers union. He negotiated the deal from a position of power and at the same time blocked more aggressive unions from trying to organize his shop in the future. In exchange, the local hospitality union got expanded payroll and power. This crafty entrepreneur now runs his shop on a 100% pull system; every night they schedule the next day's labor. They set up the production lines, know the exact staffing and throughput needed. Then they tally up the number of workers needed and call the union shop to place their order; “We're going to need 113 tomorrow, thanks.” At 6:00 a.m. 113 union workers will be ready for their shift. Wages are fair and the union hall is collecting their share of that every week. The next day, the company might only need 104 workers, maybe 120 the day after. Not a dollar of labor goes to waste this way. Compare that to how other businesses manage their labor with plenty of sitting around time when work is light.

Canadian unions are stronger than those in the United States, but they've seen enough loss in two of their largest industries (auto and forest products) to understand that globalization is not going away, and we need to fight it with something more than defeat. For the most part I've found a sincere desire to save jobs and work together with North American unions. Together, we've taken on entrenched political interests and one particular bank chairman, and so far we have won. It helps that saving union jobs in the rust belt is one of the noblest causes one can support.

Certain European unions are more resistant to change and have been known to riot, vandalize, and boss-nap in order to make their point. French workers were burning cars in the streets when I first sat down to write these words, and they are doing the same now two years later for different reasons, as I edit this. When I was living there briefly last year, the blockades at the time were staged to defend the jobs‐for‐life (waiting for a pension) compact that transportation workers have long enjoyed. It's a wonderful country but an example of how different union negotiations can be around the world.

Boss‐napping is a negotiating technique we've seen in Europe that combines kidnapping and the threat of physical violence with a hard‐lined bargaining stance. One friend of mine watched out the conference room window as the factory gates were closed and then blocked with a large truck. He was trapped with screaming French union representatives who refused to let him out or have food, water, or use the bathroom. Finally, sometime after midnight, the union representatives were convinced by my friend's doctor to let him go lest they have a manslaughter on their hands. In the Basque region of Spain, another friend was so unwelcome at the following day's negotiations that the union representatives banged on his hotel door all night, keeping him awake then they barred him from leaving his hotel room the next morning. He was unable to attend the negotiating session because union reps kept him contained in his room until the following day. To be fair, similar tactics happen in the United States. A colleague of mine was once visited at home by two gentlemen with baseball bats in Rhode Island, and a few colleagues have had tires slashed.

Again, despite some rotten tactics by a few rogues, union workers have been some of my greatest turnaround partners, and I always suggest embracing them as part of your solution in a turnaround. We've saved thousands of jobs together, shared in some wonderful successes, and had a few good tussles along the way.

The Income Statement Turnaround

Our turnaround started with cash flow and changing the business from cash‐losing to cash‐generating. It can also mean moving the cash balance from negative to sustainably positive. Positive cash gives you the freedom from creditor pressure and the financial means to fix the business.

Although cash flow is the crisis stabilization part of the turnaround, the income statement is where the actual turnaround takes place. Somehow the CEO needs to get revenues exceeding costs, and do it consistently. It's mathematically simple, but there are only a few controls to work with:

- Increase sales. If you're in retail, you can increase sales almost immediately. If you make engineered parts for large infrastructure projects or pharmaceuticals, it may take you years to actually book new orders and increase shipments.

- Increase gross profit margins. Short term, this means price increases and cost cutting. Longer term, it takes the form of product design and courageous pricing.

- Cut costs. This always works and you can (largely) control the pace and aggressiveness of cuts. Most turnarounds are cost‐cutting exercises in which the business is simply made to fit within its gross profits.

A typical first call with a business owner starts with them telling us how they have a $100 million business, but when they send the financials, the current run rate on revenues is about $70 million. “Well, it was $100 million a few years ago and that's where we need to be” is the explanation we usually hear. The entrepreneur is slowing tapping his feet waiting for the business to recover to $100 million. In those situations, I usually see a $50 million business that makes a lot more sense; it is protected with high margins, real expertise and loyal customers. Although I want to quickly shrink to sustainable profits and a business with great core strength, the owner struggles to give up the big number that sounded so great but never really worked for them. “You went from $100 million to $70 million. What about $100 million (other than your dreams) sounds sustainable to you?”

I much prefer to shrink to profitability because it is certain. The business has pursued years of speculative growth fantasies, and your lender and stakeholders have lost their appetite for any more of that. They want stability, and your business desperately needs it, regardless of the top‐line revenue figure.

With cash and stability, the turnaround continues on a script of doing more of the right things (cost cutting, price raising, new‐product development, selling, accountability) and less of the wrong things (risk, speculation, waste, distraction). Keep your head down, hoard and reinvest your cash, and everything should turn out just fine.

When you can't solve the cash issue in a turnaround, then very few options remain. In fact, you have a fiduciary duty to stop the bleeding, even if that means firing everyone and closing the doors. That's why we need a cascading set of options where we can fail‐forward into some sort of resolution. Even if it ends up in liquidation, maintaining control and extracting value for your creditors can be a dignified end.

The Salvation Process and My Worst Turnaround Result

Only once, as a turnaround professional and at the time of this writing, have I failed all the way through a turnaround to liquidation, and here's how it worked to the relative benefit of everyone involved:

Hank and Eddie were childhood friends who got into the salvage business at an early age. Things went well, and they made good money for many years. Then they expanded into processing. They had been merely brokering product over the years, making their spread (the vig) between buy and sell but never actually taking ownership or possession of the materials. They were merely brokering the spread or arbitrage between loads, and they didn't need much to support that – a small office, phones, no employees, and a part‐time bookkeeper.

Next they wanted to expand their business by buying bulk product and consolidating full shipments by actually taking ownership and possession of the material. This allowed them the brokering fee plus processing and consolidation fees and later shredding fees, but it cost them the investment in a 40,000‐square‐foot facility, forklifts, trucks, employees, overhead, and a loss of focus. The business now had a much larger monthly overhead to cover, and the owners got pulled away from sales into (nonlucrative) operational and employee issues. To compensate, they built a (mediocre) sales team that contributed more to overhead than profits. Then commodity prices cycled downward, volume dropped, margins squeezed, and their shredding operation became unprofitable. This further distracted the owners from doing what they do best, brokering loads.

In our turnaround plan, we presented the bank with a cascade of increasingly less‐desirable options; if growth and cost cutting don't work, we'll pivot to an expedited strategic sale; if that doesn't work we'll pivot to a private sale; and if that doesn't work we'll accept defeat and peacefully liquidate the business. This addresses the bank's number‐one concern, downside risk. As I've explained, the bank workout officer isn't so worried about the mess he inherited but he can't allow it to get worse.

Here's the basic framework of our salvation process:

First control bank expectations, establish worst‐case scenario and secure downside risk.

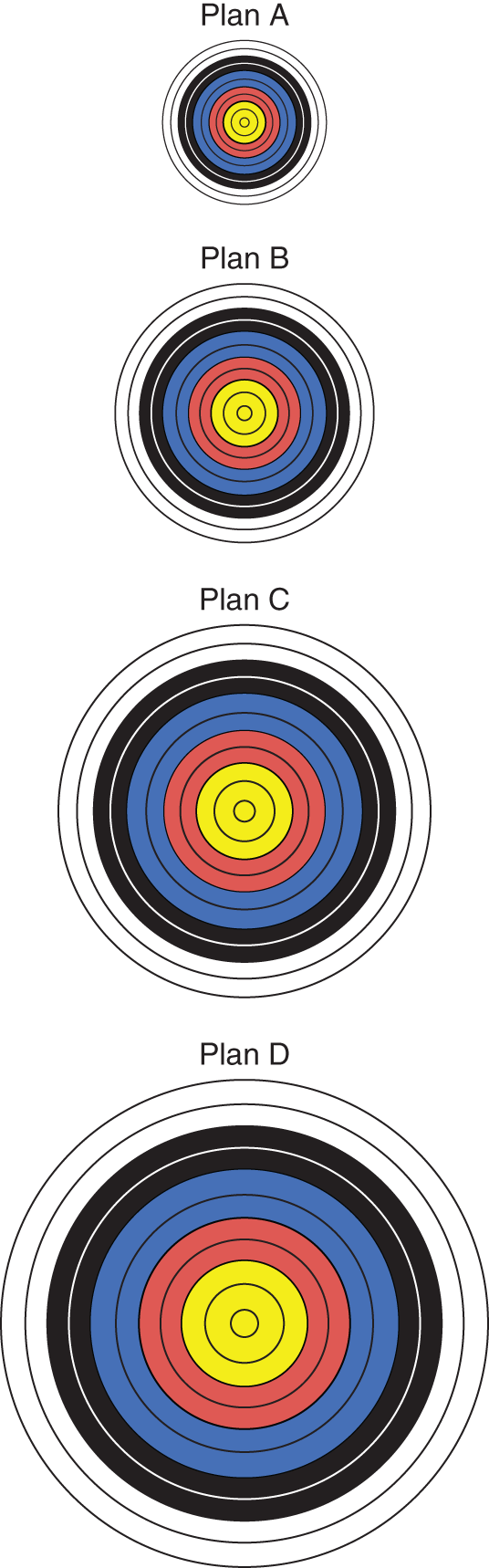

Plan A: Growth with cost controls and bank support. Plan B: Expedited sale to strategic buyers. Plan C: Expedited sale to any buyer who will find value in the business. Plan D: The last possible step, a partnership liquidation with both bank and entrepreneur working together and a release from remaining personal guarantee by the owners. The bank will likely take a loss, but it is rare to ever get here in the turnaround process.

Picture a bunch of targets stacked on top of each other (Figure 5.1). Your aim is good, we just don't know if you have the trajectory to hit your top target, growing out of our troubles. But we have good aim, so even if we don't hit the top target, we should hit the one below it. The point is, we will hit one of the targets and we've removed the mystery about what's going to happen with this business.

Establish the Base – Forced Liquidation Value (FLV)

The secured creditors have had enough surprises and will not tolerate any more. They need to secure downside risks and provide a floor of certainty to the shareholders. Figure 5.2 shows how the bank is looking at the business. (Note: I will not present the Hostile column to the lenders; we'll discuss it and they understand it well enough.)

Figure 5.1 Stacking targets in the salvation process.

Credit: Logan Sands

| Balance Sheet—Company #1 | |||

| Account | Book Value | Peaceful Liquidation Value | Hostile Liquidation Value |

| Cash | – | ||

| Accounts Receivable | 1,000 | 800 | 400 |

| Inventory | 2,500 | 625 | – |

| Total Current Assets | 3,500 | 1,425 | 400 |

| Machinery and Equipment (net) | 1,200 | 1,200 | 700 |

| Computers and Software (net) | 700 | 10 | |

| Leasehold Improvements (net) | 400 | – | |

| Goodwill (net) | 1,300 | – | |

| Total Long‐Term Assets | 3,600 | 1,210 | 700 |

| Total Assets | 7,100 | 2,635 | 1,100 |

| Bank Debt | 2,000 | 2,000 | 2,000 |

| Total Liabilities | 5,300 | 5,300 | 5,300 |

| Equity | 1,800 | (2,665) | (4,200) |

| Bank Recovery | 100% | 55% | |

Figure 5.2 Liquidation values.

The bank is owed $2 million, and if handled properly they can get a full recovery. If handled poorly they might take a $900,000 hit, or more. This is the entrepreneur's bargaining position and the art of playing poker with an awful hand. With a peaceful and orderly liquidation, we should be able to collect most receivables from the customers. With time, we can reel in aged receivables and greatly reduce the exposure and develop good will with the payables clerks. We can also convert WIP (work in process inventory) into shipments and recover prior investments in materials and labor. In a chaotic and abrupt liquidation, we lose those advantages. If the entrepreneur goes ballistic, he can poison the relationship with customers, destroy inventory, and damage or hide machinery, making recovery a much tougher prospect for the bank.

With coaching, the entrepreneur smiles and convinces the bank that he wants to do the right things and is not having crazy thoughts. This helps reassure the bank that their downside risk is secure and gives us a chance at fixing the business.

We stabilized the cash flow, dealt with all the trade partners and vendors, and got them comfortable. Then we went to the bank with the salvation process; we would pursue the best possible outcome with downside protection at the forced liquidation value (FLV or forced‐liq). The entrepreneurs were willing to play ball and would protect the bank's interest in exchange for a shot at making the turnaround plan work.

With bank support we slashed costs to the bone while Hank and Eddie, the owners of the salvage business, went full speed on sales. No amount of cost cutting was going to make this business sustainable, so a quick improvement in sales was our best option, and it seemed possible. The owners got on the phones booking work and put our available cash to work turning loads. It worked but not enough. The resulting sales fell quite short of what we needed to reach sustainability. That's normal; most entrepreneurs overestimate their ability to shift momentum and they underestimate the damage they have done to their business over the years of challenge. But, despite that, my job is to get them totally fired up and aiming for the best results. Hell, why not? If you're ever going to go big in your whole life, if you're ever willing to ever truly lay it all on the line, then this is that time.

So the owners doubled down on their sales efforts while I started writing the offering memorandum (OM, or often referred to as a CIM, confidential information memorandum) to present the business to strategic buyers. The OM is a 20‐ to 40‐page document that sells the business; it's what an investment banker puts together and refers to as The Book. A fancy investment banker will take months to produce a 70‐page book with knockout graphics, but in a distressed sale, the key is bringing quick focus to the core values in the business and not letting buyers get distracted with all the problems.

The whole book (OM) is written to present the highest possible going concern value. Remember, the company is in the zone of insolvency and our legal duty is to the highest possible recovery, not always the preferred buyer. Unfortunately, this might mean selling to a remote company who strips out operations and reduces the local workforce. It's my job to understand the possibilities and model them out for the prospective buyers. I'm an operator by nature, so I usually want to walk the plant floor with the buyer's top finance and operations executives to help them see every little opportunity available to them. We basically walk the entire P&L and Balance Sheet on foot, and I guide them to my optimistic understanding of this business. I'm selling revenue, gross margin dollars, contribution margin, the customer list, workforce, backlog, some unique capacity, redundancy savings, intellectual property, knowhow, taking out a competitor, and so on. Beyond that, it's just a pile of idle equipment in a semi‐idle factory, in a world flooded with capacity.

The key here is going concern value. Less experienced buyers expect us to sweat when the walls are clearly crashing in on us. They poke around with questions like; “You're running out of cash, why would we pay anything for a business that will be closed in three weeks?” It's a rookie question because three weeks gives us plenty of time to auction off the company at a premium price and have a binding letter of intent. With a binding letter of intent, we can probably bridge finance the next gap and keep the business alive to a sale. If we move quickly on a sale, I can be talking directly with 5 to 10 qualified, strategic fit CEOs in one week. The company's insolvency, combined with our sale process creates pressure for them and brings forth serious buyers quickly. The pressure gives us options to craft the very best deal. It's a sellers' market for a going concern, even when the building is on fire.

So, by day 15 in the salvage company we've seen what the sales effort has accomplished. We can pivot there to a sale or if things look promising we can commit to another 15‐day sales effort, with bank support. If the company is cash positive, and forecast to stay that way, we can breathe easy and think more strategically. But if the sales effort hasn't delivered the volume to get the company above breakeven, then it needs to find a new owner. We let the bank know that sales have not materialized in the first 15 days and that while the sales effort continues, we're moving to Plan B, a strategic sale of the business.

In between days 15 through 30, the owners are still pumping sales to increase our going concern value while I can write the OM, soft-pitch the business to 10 to 30 strategic buyers and have good feedback on the business and our prospects. We'll know who is likely to make an offer, their value and structure range, how it fits for them strategically, their general financial health along with the acquisition experience and bandwidth of the management team. I've had situations with no interested buyers at all (lumber yards in 2010) and others with plenty of interested buyers (aerospace machine shop with tier‐1 customers).

The strategic buyer universe for our salvage company was small but we contacted every one of them along with a number of private equity (PE) groups with a penchant for investing in small distressed businesses. The PE groups didn't see a clear strategic play. Two strategic buyers showed interest, one seemed a bit overwhelmed. That party had never done an acquisition and they were not sophisticated businesspeople, just very successful blue‐collar millionaire‐next‐door type guys. With a buyer like that I will often act as their advisor to show them how the acquisition and financing can be structured and get them comfortable with the concept. It's a great learning opportunity for them if they embrace it.

The other interested buyer was big, aggressive, and sophisticated. The CEO was a former maniac, brimming with kinetic energy who now poured his obsessiveness into work and marathons. He was the ideal buyer, 20X our volume and had no physical plant. He could fill our facility with work and save all those handling and processing fees on his much greater volume. Plus, he had a history of acquisitions, was super rich, and fearlessly aggressive. My entrepreneurs would get employment contracts, the bank would get a more complete recovery, and I'd leave with a success fee plus the invaluable thrill of saving another business. We went through weeks of due diligence until our big, aggressive buyer had sufficiently scoured our entire business, learned everything he could about us, and then walked away. Our chances of a strategic sale were dead, the bank was annoyed and we were about out of cash.

I'd been developing nonstrategic (financial) buyers through this process and hadn't found anyone yet.

A financial buyer can be a wealthy local individual or a private equity group. These private investors are usually entrepreneurs looking to own and operate a company. They are hard to find and usually not comfortable with or capable of going through an expedited sale process. To find them, I usually start by talking to banks, attorneys, and CPAs, asking for introductions to the wealthiest, most entrepreneurial people in town. It's pretty much them and their friends who will be our candidate pool for financial buyers. There were no interested financial buyers in the area, it was a tough, dirty business in a fancy New England resort area.

I had found no private equity firms who wanted this business as a strategic investment, and it was too small to be a platform investment for them. Platforms are usually the initial investment in an industry (which this would be) and they become the platform for additional add‐on acquisitions. Even the lower‐middle‐market PE buyers are looking for healthy companies with revenues over $20 million and EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization) over $2 million to become their platforms; this salvage business was neither healthy nor near $20 million in revenues.

The last and final hopes for a distressed business are special‐situation PE firms who look for small, distressed companies like this. These are known and funded buyers who can close on a transaction in weeks and even provide life support after a signed letter of intent (LOI). The conversation with them is very direct; the business is a stinker but here's how you can make it work. If I can map out and de‐risk the acquisition, then I can usually get someone to take a shot. But this recycling business lacked a clear path to success. My last question is this: “Would I take this business today, as‐is, for free?” If the answer to that is no, then it's game over.

That was it, we'd run through Plans B and C, selling to a strategic or financial buyer. It was liquidation time. The company owners, Hank, Eddie, and I had several meetings with our bankruptcy/restructuring attorney as he negotiated the liquidation plan and release with the bank. When I need to scare a creditor, I'll refer to our attorney as a bankruptcy lawyer; when we need the creditor to calm down, I'll refer to the same attorney as a restructuring attorney. They are one and the same because they specialize in insolvency issues both in and out of court and both in or out of the bankruptcy process.

We considered a last‐buy program, which alerts customers to the factory's closing and allows them to make final purchases before the factory shuts down completely. This is standard in many platform industries like auto, aerospace, medical equipment, and for the creditors it's a great surge of profitable work with very little overhead attached. Employees get another 30 to 60 days of work, and the business can conform to the WARN Act (Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act) regulations. But this was a recycling broker, so no one was interested in a final buy.

This was a failure, and the net result is that the bank took a loss, a little less than if they had just liquidated on day one. The owners lost their business, lost their jobs, were disgraced, and walked away with nothing after 10 years of hard work. Within a month, each of them had new jobs. One took a step down in pay, potential, and freedom from the entrepreneurial gig he'd grown accustomed to. The other owner embraced the idea of just being a pure trader, free of the hassles of owning and operating a business. Within a year he was earning half a million dollars in annual commissions with no personal guarantees or risk.

That's my worst‐ever outcome as a turnaround professional. We really believed the business could be saved or sold, but instead one partner ended up in a worse situation and the bank came out maybe 10% worse off for taking a chance.

Cash Flow During the Salvation Process

Before we move on, let's talk about cash flow during the salvation process. If the company is producing cash, then the salvation process is not needed. Maybe debt restructuring is in order, but not some process that could lead to a liquidation. The salvation process is needed if the business isn't sustainable but still has a chance to save itself before running out of money. Although the entrepreneur and I may feel great about this one last big push to save the business, the bank may be too fatigued to even care anymore.

Or, if you need money to finance the salvation process, you're really out of luck. The bank has zero interest in going deeper into debt on this venture, and every lender will prioritize his or her job security above your last‐ditch effort. But it can happen. With the right mix of circumstances and credibility, you can put together a last ditch plan that the bank will fund, totally ignoring the maxim about the first loss being the best loss.

Years ago, I got a call from a sensor company in New York. They were considering a bankruptcy filing and their investment banker called me to see if there might be a better solution. They had already run a full but unsuccessful sale process and were out of options. I looked at the business and hated what I saw; a poorly executed business plan, in the wrong direction, to the wrong industry, in a foreign country, with low margins. What I loved was the opportunity they were not pursuing. It was simple, recurring, predictable, niche, and had high margins. The company and entrepreneur were too far gone to fund a turnaround, but a strategic owner could do wonders with this company.

The FLV on the business was $2 million, although total debt was $10 million. Therefore, it was an $8 million loss for the bank. Our plan to the bank was to quickly find a last‐ditch strategic buyer while we kept the business alive. We wouldn't need funding during the four weeks that I thought it would take to get a letter of intent (LOI) but we would be draining inventory and receivables to cash flow our losses during that time. Said another way, we would be reducing the bank's collateral position and possibly diminishing their recovery in a liquidation. The bank was betting their money to support our efforts. Meanwhile Tony, the owner, is still driving his flashy orange convertible around town and acting like a jerk.

My first likely buyer passed on the opportunity. He liked the company but didn't trust the owner. I only had one other possible buyer, a distributor of similar products with 10X more revenue along with facilities and operations to absorb the sensor company and get it out from under a nasty landlord. I delivered an offer of $5 million to the bank, which seemed like a no‐brainer to me. The bank would recover 250% of the forced liquidation value and had probably already accrued for the $8 million in losses.

The bank refused the offer and then went silent. It wouldn't even take my calls and I've worked with them for years. The next day the bank's attorney began the foreclosure process. I know banks and entrepreneurs expect miracles from me, and I'd pretty much pulled it off with this sensor company. The bank would get a $3 million premium value while the company would survive, the entrepreneur would have a fresh start and earn equity going forward. The buyer would have a great little niche business that could be run like a cash machine.

But the bank was not happy, so the whole deal fell apart and everyone wandered off. At that point I'm playing the role of investment banker, so I begin shuttle diplomacy going back and forth between the three parties. The bank is coldly saying they prefer to see blood than take this deal. Tony knows it's curtains for him and his personal guarantee, so our only real bargaining chip is threatening (through his attorney) that Tony might destroy everything if the bank doesn't take this deal. He will sue and lash out and be dangerous in his actions (“you know, a guy like that can cause a lot of damage in a short amount of time”). This creates risk and uncertainty with the bank and they don't like that. Fortunately, Tony was enough of a jerk that the threat was believable. It's a stalemate. The buyer says to call if something develops. Me, I'm screaming at everyone about going concern value. The business is imploding, cash is draining, the customers are leaving, and jobs are disappearing. If they don't need me, then we should just call the auctioneer.

Three weeks passed, and the company continued to burn cash (the bank's cash) while deteriorating in value. The bank was burning cash on its attorney and this situation was top of the agenda in credit committee meetings. No one was happy. This was the suboptimal path, and I remained convinced that there was still a deal that could happen here. After much stomach acid on all sides, we finally structured a $7 million purchase price. It was still a good deal for Frank, our buyer. He got a great little business with proprietary products and a high potential sales leader in Tony. Tony got an employment contract plus stock options in the new entity. The bank got a 350% premium on auction value and the community kept most of the jobs while retaining a healthy, restructured manufacturing business. Me, I got a success fee, declared victory, and went home. We all benefited from the bank's patience and willingness to fund the company while we explored options.

It ought to be remembered that there is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things. Because the innovator has for enemies all those who have done well under the old conditions, and lukewarm defenders in those who may do well under the new. This coolness arises partly from the fear of the opponents, who have the laws on their side, and partly from the incredulity of men, who do not really believe in the new things until they have had a long experience of them.

Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince