Chapter 1

Understanding Corporate

Turnarounds

If stupidity got us into this mess then why can't it get us out?

—Will Rogers

The U.S. Federal Bankruptcy Court in New Orleans would never be described as regal or stately. Instead of marble floors and ornate molding it held all the charm of a Soviet era department of motor vehicle office: pale fluorescent lighting washed the stale air, dingy yellowing cinderblock walls sweated with the morning's dew. Metal chairs were lined up in orderly rows across the dead linoleum tile. A judge and her clerks worked behind two large wooden tables stacked high with files. It was just me and all the other losers assembled there that day to file personal Chapter 7 bankruptcy. I had a 780 credit score but that was about to tank because I'd personally guaranteed corporate debt on our family business prior to Hurricane Katrina and was now at rock bottom of society surrendering my assets to the court in exchange for a release of my debts.

Forty years of my life had led me to this low point. Our family home and neighborhood were wrecked in the storm, so my wife, our three young children, and I spent eight months living in a small camper in the driveway while we rebuilt the house on nights and weekends. My participation trophy was this day in court. I'd reached bottom and it was time to push off and rebuild, but I had few options; no corporation would hire a failed entrepreneur and I was dead broke without money to start or buy another business, and my credibility and confidence were both pretty well shot. Metaphorically I was naked and alone, picking myself up from the dust of my own failure. Every bone in my body yearned for security and comfort, and I dreamed of a cushy corporate job at a cushy company far away from the chaotic and punitive nature of insolvency. Well, almost every bone in my body yearned for that security and comfort, a small upset part of me wanted to stay right there in the dirt and fight my way back, which is ultimately what I did.

In those brief moments when my mind was not racing with anxiety, I reflected back … I'd played my cards wrong. I zigged when I should have zagged. The bank and its attorneys always seemed to know what was happening, but I rarely did. My corporate attorney didn't understand insolvency, whereas my bankruptcy attorney was a one‐trick pony who only knew how to file bankruptcy. I'd been a checkers player trapped in a game of chess.

I'm a godawful loser, so I began to obsess about what could have been. I gave up hobbies and casual reading and churned through every book and article I could find on the topics of insolvency. I re‐read all my college finance and accounting textbooks and obsessively relived the last five years of my life which had led me to this gut‐wrenching failure. I sought out corporate turnaround pros and befriended them. I talked my way into interviews with most of the major East Coast restructuring firms, I helped friends with their challenged businesses and took a terrible job with a distressed art company just to get back in the arena (plus I desperately needed a paycheck). Eventually, my father gave me the boost of confidence I needed to launch my own consulting business focused strictly on corporate turnarounds. Five lean months later I landed my first real assignment, a Detroit machining company whose sales had dropped 90% in nine months. The bank was hostile and moving aggressively toward liquidation, and the owner was leaving for three months of intensive cancer treatments. I hit that place with a vengeance and dug in for the battle of my life. For the creditors we were just another Detroit business going down the tubes in 2009, but for me and 80 families it was personal; this was the rematch I'd been obsessing over for years. I went straight for the jugular, every jugular, and they went straight for mine. I was there to save 80 jobs, but I was also there for vengeance, and this heartless, bureaucratic banker was merely a proxy for the heartless, bureaucratic bankers I had to deal with in my own insolvent company. I was punching through targets trying to reach back and alter history. It was a street fight, but it worked. We turned profitable in month two and stayed that way. The business healed me as much as I healed it and I left Detroit with a calm confidence that I hadn't known in a very long time.

For 18 years now, I've worked exclusively in distressed businesses, five on my heels as an outgunned, stressed‐out entrepreneur, and the last 13 on my toes as a corporate turnaround specialist helping entrepreneurs keep their businesses, wealth, and dignity intact. This book is written for the beleaguered entrepreneur that I once was and all the ones I hope to help over the rest of my career. This is the book I should have read before I first personally guaranteed corporate debt. It's a complete primer on fighting your way out of corporate distress, saving jobs, fortunes, and the communities they support.

Turnarounds versus Corporate Change

In my MBA program, we studied corporate change agents, the people who initiated and championed change in big corporations – you know, the crowd celebrated in pop management literature. But this is as deep as our study went: heroic characters like the team who launched Post‐it Notes off 3M's massive and stable balance sheet. We never touched on insolvency or distress and we darn sure didn't discuss personal guarantees and debt collection. It's as if we studied life without ever considering illness and death.

Despite this failing in education, everyone pretty much knows that corporate turnarounds happen and are generally a good, though uncomfortable, thing. Turnaround is an imprecise term in corporate parlance. Sales managers claim a turnaround when they increase the top line. Presidents and general managers claim a turnaround when they produce significantly better profits and CEOs when they produce a significantly stronger balance sheet. Most mainstream business books and magazines have a loose definition of turnarounds ranging from banal change to trauma surgery, each associated with symptoms of decline.

Turnarounds are often like a corporate illness; sometimes a person or business just gets a bit of malaise and they need a little pick‐me‐up to regain focus and motivation. Sometimes the underlying issues are more serious, like flattening sales, where we just need to get the top line growing again. Turnarounds get interesting as the problems stack up; combine your malaise and softening sales with growing overhead. Throw in margin compression and factory bottlenecks and you start needing some real turnaround expertise. The problem here is that the entrepreneur or CEO has probably never been through this before and probably doesn't really understand the balance sheet as well as they should (I didn't). So, the CEO bravely tinkers with the business but doesn't move out ahead of the problems.

But imagine that, as a CEO, you've persevered in maintaining your entrepreneurial optimism and remained convinced that the angel of good fortune will return to you as she had at other critical times in the past. But this time she's late and you just lost a key employee, customers have taken you off the bid list, and vendors are shutting you off. This is when you are sliding on ice, turning the wheel of your car, pumping the brakes but not changing the business's dangerous trajectory.

At some point, you'll trip one of the financial covenants in your loan agreement, which means it's very late in the game, because these are backward‐looking formulas. The game‐changer is tripping the approximately 1.2 minimum debt service coverage ratio, which is a trailing 12‐month calculation, so it's old news by the time you trip it. When this happens, you'll be called to the carpet at your friendly neighborhood bank. This is an awful experience, but in reality, it is great news because you now have concerned and committed partners focused on your business. They exert all sorts of pressure and may hand you the name of a turnaround consultant. Because they are a bank, the consultant they recommend will likely be a vetted and experienced professional who they trust in situations like yours. You will suspect this person is an agent for the lender and working counter to your interests; it's only natural to have that suspicion. I've found that most turnaround specialists are more like surgeons – trusted professionals who are fully committed to your long‐term survival, regardless of your personality or how much near‐term pain you'll have to endure.

The worst crisis situations require a special breed of turnaround pro, someone with a perverse love of the challenge and a deep emotional commitment to their work (a grudge from prior failure helps). Imagine you've got all the troubles we've previously discussed and then federal agents raid the facility. Customers scatter, the lender calls the loan, the union is unpaid, the IRS is foreclosing, 401k trust funds are missing, your accounting is a disaster, and vendors all hold you hostage. There are actually people who can't stop smiling when they get to fix these disasters. The higher the flames the happier they are walking in the front door.

This book discusses the techniques, tactics, and strategies deployed in the most pressing turnaround situations because a good crisis amplifies issues and brings about clarity. Collecting receivables more quickly is interesting in a huge corporation because you're saving a few days of interest on the receivable balance. Failing to collect sooner has zero downside risk. Collecting receivables in a crisis might keep the lights on while your downside risk is oblivion. When the utility shut‐off crew shows up in your parking lot you only have one option, you must write them a check on the spot – and then run to find the cash to fund that check within the next couple of hours. You will either fund that check or surrender to your creditors. That clarity of mission helps everyone appreciate the value of collecting receivables. In a financial crisis, most downside repercussions are fatal, but I think that helps the organization focus, prioritize, and develop a clear understanding of what's at stake.

Whoa, I Didn't See This Coming

At 35 years of age I was rudely introduced to the world of turnarounds. It was our family business. Sales had tanked and our bank was upset. It suddenly dawned on me: “Hey wait, these guys are playing tackle and I thought we were playing touch, plus I don't know a darn thing about fixing companies.” But how could that be? I had an economics degree and an MBA and spent eight years working outside the family business for companies ranging from Fortune 300 to a biotech startup. I'd read all the pop‐management books and subscribed to several business magazines. And nowhere in all of that had I learned to run a business in distress. I went home and thumbed through every college textbook and business book I owned – nothing. The next day I went to the local mega bookstore, which had four bookcases full of management books and not a single title on turnarounds. We know that every company goes out of business eventually and we know that down is half of any cycle, but no one seemed to talk about it.

The lack of knowledge is so pervasive that corporate managers rarely know they have this educational deficiency until they are in deep trouble. And when they find themselves in a workout they don't know how to get out, don't know where to go for resources, and few even know the key search terms to find help online. In my first turnaround, we made it to Stage 4 (out of 5) before I learned there were even stages in a turnaround and what they were. We were a year or two into our turnaround before I stumbled on the Turnaround Management Association (TMA; www.Turnaround.org) and got myself oriented.

The TMA tests on the five stages of distress for their certification program, but they were first detailed by Donald B. Bibeault in his seminal work on the subject; Corporate Turnaround: How Managers Turn Losers into Winners (McGraw‐Hill, 1981):

- Management change

- Quick evaluation

- Emergency action

- Stabilization

- Return to normal growth

The book I am writing takes the reader through those stages, though not formally because the true joy and artistry of corporate turnarounds is the creative dance in that very thin space between the hammer of your creditors and the anvil of insolvency law. Cash gives you that space, and understanding the following two core principles is the key to saving a business when all the odds are stacked against you.

Two Core Principles Needed to Understand Corporate Distress

There are only two types of turnaround: (1) income statement turnarounds or (2) balance sheet turnarounds. Both necessitate positive cash flow. The former involves running out of cash from losses and about to stall mid‐flight. The latter may involve a stabilized business with suffocating levels of debt. Maybe half of my clients have suffered from both ailments at the same time. Both problems present themselves in a cash crisis so the initial solution is the same – control and grow cash. Managing the cash conversion cycle (CCC) gives a company the cash it needs to survive the early days of a turnaround, whereas the priority of debt (debt stack) determines who can seize your assets and who gets paid in the debt restructuring. These two core principles underlie everything in this book which is why we're going to spend a little time here in review. Once you understand these principles the rest of the book will fly.

Cash Conversion Cycle

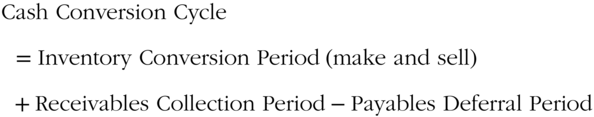

The cash conversion cycle (shown in Figure 1.1) is the single most reliable, simple, immediate, and valuable lever in all of business. If I had to live an entire business career with only one tool it would be this one, hands down. If you manage your cash conversion cycle well, you can literally shift millions of dollars of cash from other people's businesses into yours. But if you screw it up, you can do the opposite and quickly go bust.

Figure 1.1 Cash conversion cycle.

The CCC is your cash‐exposure window, the number of days that the working capital of your business is tied up funding the operations of that business. It's the time and money invested in turning iron ore into a new car rolling off the showroom floor. It is the time needed to sell your inventory plus the amount of time needed to collect receivables minus your vendor payment terms. Each of these factors are variable and as a CEO you can influence each to your advantage. If you can pay more slowly for expenses, it keeps cash on your balance sheet and off your suppliers. If you collect more quickly, it moves cash from your customer's balance sheet onto yours. When you need the cash more than them, you should “borrow” from them. The core of a turnaround is shifting your balance sheet to absorb the impacts of distress, then shifting back toward reinvestment and recovery, and managing the CCC is the quickest way to achieve that.

The formula for the cash conversion cycle is:

Each variable is measured in days.

I'm currently involved with the restart of a steel fabrication business that went bust and stuck the vendors with more than $10 million in write‐offs, so vendors are being miserly in extending us new credit. We can buy steel rolls from the distributors (service centers) with 30‐day payment terms, but they don't always have what we need and we're paying a lot more than going direct to the steel mills. But the mills won't give us any credit and, in fact, are making us pay cash in advance (CIA) because they are so credit averse with an unproven company. This means paying 45 days before we will receive the product. So between paying 45 days before delivery to the mills or 30 days after delivery with the service centers, our choice is price versus 75 days of cash. It's a metric that changes daily (see Figure 1.2).

A 12‐week delivery time is the historically fastest attainable speed in this highly engineered, heavily regulated, little niche of the steel fabrication business. Over decades, this company and our competitors have wavered between a low ship time of 12 weeks and highs as much as 36 weeks. This in‐between period of time, the 24 weeks between 12 and 36, is all cash‐consuming waste. Every week is an extra week of payroll and supplies. Every month is an extra month of utilities, rent, insurances, and other operating expenses.

Figure 1.2 Range of days payable.

We rebuilt this company from a dead stop and quickly brought it back to breakeven, but then sales stalled and we just bumped along at breakeven for a few months, never accumulating enough cash to move to the steel mills and lower our costs or to invest in upgrades of equipment or people. Then sales tripled, which put a big strain on cash because we needed to buy more rolls of steel. We knew we were entering a virtuous profit cycle, but we needed the cash to do it. The weaknesses in our production system started to reveal themselves. Shipping times grew from 16 weeks to 20, then 24 weeks. We're clubbing it back down now from a high of 26 weeks as I write this.

Those 10 extra weeks (70 extra days) was pure cash burn. It's 70 days of not shipping but still incurring expenses daily. We'll get that cash back as we reduce our ship times (converting inventory more quickly), and with growing sales and growing margins, there's a lot of sunshine on the other side of this challenge (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Inventory conversion cycle – time to make and sell.

Figure 1.4 Receivables collection period.

Our products are components of much larger commercial projects performed by deep‐pocketed government contractors and deep‐pocketed integrators, so although they are currently pounding on us for the delayed shipments, they are also paying us on expedited terms to help get us through this cash crunch. Our ability to collect faster is the only offset to these Payable and Inventory issues (see Figure 1.4).

Obviously, our steel fabrication business is an expensive model to operate and fund, but it is typical of most industrial businesses. A retailer gets paid at the cash register, so they don't have the collection period. It is the same with most consumer‐facing businesses. For them managing the CCC is all about inventory management. Bananas and apparel both need to be sold before they go bad or out of style, hotels and restaurants need to manage their inventory of empty rooms and seats. A grocer may be turning milk inventory daily, for cash at the cash register and then paying the dairy on five‐days terms, meaning that the grocer has a four‐day positive cash cycled on its milk business. Software businesses will have a large sunk development cost but no real conversion cycle and no collection cycle. Automatic prepay subscription businesses with no physical assets and generous vendor payment terms are the ideal cash machines.

Debt Stack

My favorite legal axiom in insolvency is the Absolute Priority of Debt Rule. It's absolute and sets the priority of debt so no one needs to argue about who's getting paid first or who can foreclose on assets. It's all in the loan documents and on file in public UCC‐1 filings (liens). Our family business sold to Kmart, and we got burned for $300,000 in their bankruptcy. I was young, so I acted emotionally; let's go sue, take up arms, sully their good name, and so on. We wasted money having our lawyer check things out. I was new to the game of insolvency, but the law is not. Banking goes back to 5,000 BC, and I suspect collateral is discussed in Genesis. The rules of who gets paid, how, and when have been established through millennia, and that's why it's called the Absolute Priority of Debt Rule. Talk to your lawyer, then swallow your outrage and take your position in line.

For clarity, any commercial debt stack must first pay all earned wages. This is an absolute in the United States and most other countries, and earned wages are assumed to have been fully paid in the following discussions. Beyond wages, there is a stack of debt with the senior secured lender in first position. Two more easy terms to figure out; this party is both senior and secured, so they have first collateral lien positions on the company's assets. This is typically commercial loan(s) from your local savings bank. The junior secured position is similar, though they have accepted a position subordinate to the senior but above every one else. The secured position is so revered that even the most aggressive federal collection agencies will respect the lien position and not use their unlimited powers to usurp the senior secured lender's position. This means that the IRS and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) will generally sit behind the senior secured creditor.

A simple private company will have leveraged (borrowed against) their Accounts Receivable and Inventory with what's called a Revolver or Revolving Loan (the balance fluctuates or “revolves” with collateral values). Additionally, they're also probably borrowing against fixed assets (equipment, real estate, intellectual property, etc.) and paying that out over a set term of years. This is called a Term Note because it's for a term or number of years and then terminates. The structure mirrors the useful life of the assets that collateralize the loan: long‐term borrowing on long‐term assets like machinery and short‐term (revolving) borrowing for short‐term assets like inventory and receivables. So one loan is backed by a senior secured position on short‐term assets (Accounts Receivable and Inventory) and the other loan is backed by a senior secured position on long‐term assets (machinery). A mortgage may hold a senior secured position on the real estate as well. So potentially, three senior secured lenders, each with first positions on distinct assets of the business. These three lenders will file paperwork at the county court house for each individual loan, establishing UCC‐1 liens against each group of assets. Then it is public record, established by date of filing, for who has what liens and positions on what assets of what companies.

Our fictitious company anticipates growth and gets a second level of debt. This may be from a merchant's cash advance (MCA) company they heard advertised on the radio. The MCA lender files second‐position liens on the assets of the company that establishes them as the second or junior or subordinated secured lender and assures that if there was a sale or liquidation, 100% of the money would flow to the account balance of first‐position lenders (Lender 1) and once their account was paid in full, 100% of what remained would flow to the account balance of second‐position lenders. Sometimes much money flows to and beyond Lender 2, and sometimes none at all with a deficiency to Lender 1, even as secure as they once were.

Occasionally a $100‐million‐sized business will have third‐level secured creditors and often they are state economic development type lenders, a second merchants cash‐advance lender, mezzanine debt, or even a savvy father‐in‐law who lent you money and filed a lien to protect himself. It could also be a vendor or landlord who somehow negotiated their way up the debt stack and secured a claim on business assets, something you would have agreed to. In all these cases, the company (the borrower) explicitly grants rights to the lender or merchant to place liens on the company's assets as part of the loan documents or commercial contracts. If the borrower defaults on a loan, the lender can foreclose on the collateral that backs that loan. Even a third‐level lender can foreclose on the assets, causing great distress to the borrower.

Credit cards are personally guaranteed by personal assets (this is often unknown and usually by the majority shareholder, whoever signed the credit card application and supplied a social security number), which means that, if a company defaults, the shareholder is getting sued personally for collection. All the sudden assets like your house, car, paycheck, and savings can be in play.

The tier below secured lenders is unsecured lenders. These are usually vendors who extend you trade credit as part of their commercial relationship. If terms of a sale are not specified (often on the purchase order or invoice) then the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) specifies standard terms of trade within industry. For the seller, extending credit terms is part of their business plan and factored into their model (their days in their own cash conversion cycle). They manage the risk of this small window of credit, usually only 30 to 45 days, to fund what is usually a profitable multiyear supply business. While a bank can lend a lot of money very quickly and have tremendous exposure, vendor credit is usually managed and moderated and is rarely even half of the annual contribution margin generated by the sales to that customer. In a low‐interest‐rate environment, extending credit might be a very inexpensive way to compete with a competitor's low price or lock in volume from a customer. There is risk, of course, which is why sellers manage these accounts closely. Unsecured creditors are usually all equal in status and they are called the general unsecured class of creditors. This is the bottom of the debt stack, and if money flows past the secured creditors to the general unsecureds, it is distributed pro rata amongst them.

To recap, if Creditor 1 doesn't get paid in full, Creditor 2 gets nothing. If Creditor 2 isn't paid in full, Creditor 3 gets nothing. If all the secured creditors are not paid in full, then no money flows to the unsecured creditors. You can see the risk.

Figure 1.5 Example private company debt stack.

Credit: Tatum Sands

Figure 1.5 illustrates the debt stack of a midsized private company. A large public company or a private venture‐funded business will both likely have a more complicated debt stack, perhaps with bonds or multiple levels of debt, and preferred and common stock.

Now that you're refreshed on some basic concepts, let's examine how you may have slipped into trouble in the first place.

23 Business Killers

Before we get started on the turnaround, let's step back and consider how we may have gotten into trouble in the first place. Some businesses are terribly resilient; they can mismanage time and again, while the customers keep coming back for more; whereas other businesses might be in a shrinking industry in which any trip‐up might be fatal. Business distress is a natural state of being just as our body aging is the natural course of events for humans. Sure, we can fight decline, but we all know how the movie ends – entropy. The knowledge I share in this book won't change physics but it will give a business a clean bill of health, several more years of vitality, plus the strength and vision to fight future battles. But let's face it, the following challenges never go away. In no particular order, here is a list of landmines that scatter the field of business and human behavior:

- Failure to adapt. Despite popular misconception, Darwin never said it was the strong that survive, but the adaptable. The economy is always in flux; how we read and react to that change determines our longevity.

- Bad luck. A motivational speaker might tell you there is no such thing as luck, luck comes from preparation, or something shallow like that. But mention a factory fire, loss of health, natural disaster and everyone acknowledges that bad luck exists, and sometimes it finds you.

- Undercapitalized. Occasionally I judge business‐plan competitions, and not once have I seen a hopeful entrepreneur ask for enough money. A strong balance sheet will get you through the worst storms in business. My opinion is that in turnarounds luck tends toward the downside, and you need to quickly accumulate the capital to survive those jolts.

- Overlevered. Similar to undercapitalized but more dangerous. Dancing too close to the edge leaves no margin for error.

- Not diversified. Investors discount the value of a business based on the risk of customer, vendor, or product concentration, or an overreliance on key employees or markets. These are real risks, and as the CEO it's your job to minimize risk throughout the organization.

- Lacking controls. Running a business is more complex than flying an airplane. I've student‐flown a couple of airplanes, and I prefer a working instrument panel when I do; things like altitude and airspeed are as important as cash flow and backlog when running a business. For many businesses it's the lack of controls that gets them in trouble, they simply don't see trouble developing and often misread the magnitude when they do. The ideal formula for avoiding trouble in your business is relevant measurements and timely reporting followed by swift corrective measures.

- Overanalyzing. I was recently in a company that measured so much I couldn't make sense of it and neither could management. Profits swung $8 million in one year and 87 different metrics pointed to 87 different symptoms, which made simple problems even more confusing.

- Low gross product margin (GPM). Sales minus the variable cost of your product or service, it's the money you have left over for everything else, namely overhead and profits. GPM is the first number I look at when analyzing a business. Every industry and business model has a standard GPM range that the industry runs on. You should be in the high end of that range.

- Falling sales. Hear the alarm bells? If your airplane is mysteriously losing altitude don't expect that it will mysteriously gain altitude next year. Talk directly to your customers to find out why sales are down.

- Rising costs. This could be the pricing on commodity inputs, foreign currency exchange rates, or just the uncontrolled escalation of American healthcare costs. Rising costs need to be fought aggressively and quickly passed on to your customers.

- Owner health. It's everything. I know an entrepreneur who was bedridden and out of sorts due to some strange neurological issue that was set off by turnaround stress. Only after 18 months did doctors stumble upon the correct diagnosis and treatment. Healthy people have a hundred wishes, unhealthy people only have one.

- Owner distraction. Is the owner off enjoying his first boat, second home, third wife, and no longer grinding it out in the shop? The bank notices that you're off enjoying their money and so do your employees.

- Overexpansion. Nations and businesses both fail by living beyond their means. If nothing else, in business always remember that neither good times nor bad last forever.

- Overcomplicating. Business is simple: buy low, sell high, keep most of the spread. Don't lose sight of that, it's a simple mechanism that needs to produce cash. Too often, we see meticulously crafted financial statements with big year‐end adjustments. They are “wrong to the penny.” If you can't explain it to your board in one typed page, you probably shouldn't be doing it. I heard a story of a billionaire who was building a new pulp and paper mill and had brought in a team of experts to manage the project. As experts do, they complicated the heck out of an already complex project. Frustrated, the billionaire slammed his hand on the table and asked, “What the heck does any of this have to do with making me piles of money?”

- Regulators. Cultivating a friendly relationship goes a long way. Much more on this in Chapter 6.

- Failure to control a crisis. Stuff happens, how you react will magnify or reduce the danger.

- 2009 credit market. Hopefully we'll never see that again but let it be a reminder.

- Management transition. Management changes are always risky. Recruiters tell me that the odds of hiring the right new general manager or president through an expensive and exhaustive retained search is only 40%.

- Reading too much pop‐management. Yes, that young bring‐your‐dog‐to‐work, flip‐flop‐wearing entrepreneur made the cover of some magazine. But the tight‐fisted 60‐year‐old entrepreneur in your town's industrial park has proven the ability to create generational wealth through decades of turmoil. He's not making magazine covers but he's got no debt.

- Falling in love with your product. Like your own kids, they are perfect in your eyes, but maybe not in the consumer's eyes. Nothing kills the ability of a business to pivot more than an entrepreneur's adoration of his product.

- Entrepreneurial stubbornness. Your enviable ability to grind through obstacles has taken you this far, but in a turnaround situation, stubbornness can become a liability. Your customers, employees, and vendors may admire and support your stubbornness, but your bank expects nimble‐footed compliance and better results. Doubling down on the same old thing now will kill your credibility.

- Pain tolerance. Similar to stubbornness, but worse. At some point, everyone knows you're failing but you. Everything is going south, the bank is twisting your arm but you're tough, you're gritting your teeth and enduring the pain, proudly pushing ahead on your chosen (reckless) path. The bank, your employees, your customers and vendors, they all want you to stop, accept reality, and change direction, but you just barrel on ahead. Things get worse and you just grit your teeth tighter. Eventually this gets resolved in one of three ways: the entrepreneur relents, the bank has you locked out of your own business (called receivership), or you sneak past both obstacles and destroy the business on your own.

- Leadership. You are the only one who signed the personal guarantee and you are the only one who might be driven into personal bankruptcy. This is not the time for group decisions. Your neck is in the noose and your management team is most worried about keeping their jobs, it's a conflict of interest that the entrepreneur must solve.

Warning Signs

Yes, we should have seen trouble coming but we didn't. Looking back the warning signs were all there but often they were noticed too late (poor reporting) or the entrepreneur just failed to recognize their magnitude. A list of common warning signs are:

- Loss of customers, decline in bid requests, shrinking average ticket price, or lack of new product development.

- Declining gross profit margin, expanding overhead, increasing commodity prices, shifts in the market place, or foreign exchange rates, and so forth.

- Loss of key employees, increased turnover, losing key sales people, or changes in marketing.

- Distraction of owner or key executive, softening of the scrappy entrepreneurial culture or complacency.

The Job Ahead

Okay, so now you're in a turnaround situation. You've got jobs to save, debts to service, your own neck in the noose, and you'll have to break some eggs to make this omelet. Yesterday you were a kind and generous business owner. Euphemisms like, “I don't need the best deal, only a good deal” really appealed to you and you tried to lead your company like it was part of a wider economy where your vendors need to make a good margin, your employees deserve a good living, and your customers need a good price. Well, they all accomplished that and now you're the clown in workout. You know that old adage that if you don't know who the sucker is at a poker table, it's probably you? They're not in workout, you are. They're not going home to study bankruptcy schedules, to tell the wife to sell her jewelry, and wonder what your house might fetch at auction – you are.

The turnaround process is always the same, but what you have to work with never is. If I have cash and lots of options then success is almost a guarantee. If the owner/manager has burned up all his credit and goodwill waiting for the order fairy to show up, then we have significantly less to work with. In the first hour of any turnaround I try to ascertain the following factors that will influence my prospects for success:

- Does your business even have a reason to exist? Seriously, are you selling typewriters in 1998? Are you a small, nothing special retailer in 2017? If you are, a dignified exit may be your best alternative.

- Time and creditor anger. Which creditors are upset and how long have they been upset? If you're just lapsing over 30 days in payables, then we have plenty of time. If both your bank and the IRS have run out of patience, we need to move quickly.

- Personal guarantees and regulators. Both can bury the entrepreneur and cause him to lose hope. If his house is being foreclosed on by multiple creditors, I will struggle to keep him focused at work. The ability to keep the entrepreneur engaged is often critical to the turnaround process.

- Mental health of the CEO. Is the CEO clear‐eyed, paying attention, and willing to do tough things, quickly? If I have a soldier ready to sacrifice for victory, then we can achieve great things together. But often CEOs, especially entrepreneurial founders, are self‐destructive, usually it's passive‐aggressive behavior (denial, pride, confusion, fear) but occasionally you have either a sociopath (I've had a few) or some spiraling‐out‐of‐control behavior (I had one who ended up in the psych ward after I walked off the job). Unsurprisingly, good old‐fashioned vice can also bring people down. True story: my friend owned a company located in another state, his CEO had become increasingly erratic with tales of “lady friends” visiting his corner office midday for long locked‐door meetings. Eventually the CEO and his “lady friends” moved into the trailer behind the factory and didn't emerge for four days – until the owner showed up and fired him.

- Cash flow and balance sheet. Cash is your oxygen, the business will not survive without it and you'll need to convert your balance sheet into cash. If that's not enough, you'll need to convince your customers and vendors to convert their balance sheets into cash for you to use for your business. A few quick questions will help me determine how much room is available here.

- Crisis readiness of your team. Sometimes companies are filled with average people who really want to win. They may not be the all‐star team, but they're tired of losing and are seriously committed to saving the business. I see this more in rural areas with few good options for alternate employment and a strong natural work ethic. The opposite can be true in strong union towns.

- Prospects for a sale. If all else fails, can we sell the business to protect jobs, vendors, community, and so on? I could still sell a small print shop in 2017 but might not be able to in 2027.

- Your industry and the available levers. Ask me to fix an operating factory with a defaulted mortgage and I'll fund it by squeezing cash out of inventory, receivables, three shifts of labor, and engineering, new product development, Capex, deferred maintenance, and so on. These are short‐term tactics but they are all available to me. Ask me to fix an empty commercial building and there is not much I can do other than hire a realtor. The levers available to you at the start of the turnaround will guide your strategy.

How Hard? The Ethics of Turnaround Leadership

A friend once asked me about my business of saving companies and it seemed a bit slimy to him, you know; layoffs, delayed payments, restructured debts, and so on. I make a living from other people's misfortune, and I see how that could appear predatory in some way. I was caught off guard by his comments and thought about it a bit. My father‐in‐law is an orthopedic surgeon, which is a magnanimous career, but let's face it, no one sees him by choice. Something pretty rotten needs to happen for him to get patients. My wife is a nurse, and as lovely as she is, healthy people never employ her. I won't equate my work to theirs, but we all help people in need for a fee and then we leave.

Years ago, I was deep in an awful turnaround. The company had failed through multiple consecutive owners over several years, and now it was our turn. Nothing worked, things fell apart faster than I could even stop them, let alone make actual progress. My partner suggested the next three extreme tactics necessary to save the business, all of which made me blanch to even consider. They were aggressive, guaranteed to horrify every stakeholder, and would risk whatever faint pulse remained in the business. Our odds of success were miniscule.

I protested. I lacked the courage to try harder. He leaned across the table, stared deep into my eyes, and said in rising tones, “The employees cannot be sent to the unemployment line. These people have shown up for work every day for years, when they were sick, when they didn't want to. They did it to make sure product got out the door. They have given everything to this company and they deserve to have someone fight for their jobs. They've been screwed over for years because no one cared enough to fix their company. Now they want us to fight for them and that's what we must do. The vendors want us to fight for their money, the customers want us to fight for their products. They all deserve someone who will fight to the death to save this business, someone who won't get queasy when tough measures need to be taken. That's what we're here to do and that's what we're going to do.”

And we did. It was a complete bloodbath, but two months later the company turned a small profit and the turnaround had taken hold.

Now You're in a Turnaround, What Next?

First breathe deeply and summon your energy, it's going to be a long ride. My first turnaround started with an unpleasant visit from our bank. Afterward my father, brother‐in‐law, and I sat around, a bit dumbfounded and caught off guard. My father said, “There's nothing we can do this afternoon, go home, take your wives out for a nice dinner, explain to them that the next six months are going to be very difficult and that you'll need their love and support to get through it.” Turnarounds take a heavy toll on marriages, families, and your health. They create inordinate amounts of stress and I advise CEOs to watch for it. Sometimes it's obvious, like the 70 pounds I saw a printing CEO put on in less than a year or often just the temptations of vice to relieve the stress.

Once you've got your head right, realize that this is your big‐boy/big-girl day to step up. You allowed this mess to happen and you're the one who's going to clean it. At this very moment you are sitting on nearly tectonic amounts of personal power. You literally have the ability to reshape your entire life and many others by the choices you make in the coming days and weeks. Many entrepreneurs go from years of treading water to stunning wealth through the deep dark valley of a turnaround. They do this with courage and a mad obsession to make things right. The momentum you will create can shape generations of wealth. The heroic, come from behind, turnaround script is as old as humanity and is an incredibly powerful wave to ride. But it takes a big, conscious commitment. Accepting what's ahead in a turnaround is the most grown‐up, adult decision a business leader can make.

Your courage will protect and immunize you from the wearying psychological grind of a turnaround. Your emotions will swirl and spike, but so will those of your employees and lenders and vendors and customers. You need to remain the coolest head of all of them. This is your task; you need to own it and wear it fully.

Don't Be Cleopatra

It's a silly joke but one we all tell, you know she was the Queen of The Nile – Queen of Denial. Okay, it's hardly humorous but it does make the point: the sooner you face your problems, the quicker you can heal. Denial is completely natural, so expect to go through the five natural stages of grief in getting past it. The key is you just need to do it quickly. On my first turnaround, my denial was intense, and I held on hard for 24 hours before relenting. But when I broke down and accepted the situation, I quickly spun my thoughts and energies toward a solution. Often debtors can waste precious months clinging tight to their delusion while hope and options fade.

Debtor Psychology

Another old joke in our business is that turnarounds are 50% operational, 50% financial, and 50% debtor psychology. In the United States and many Western countries, the debtor stays in control through the insolvency process so you have the person who got us in trouble responsible for getting us out of trouble. Getting them out of denial and back into reality is paramount to saving the business.

The U.S. system in particular is heavily weighted toward liberty, which allows business owners to get fatally out of control before anyone can reel them in. Banks are working on trailing 12‐month averages, CPAs don't seem to be proactive in these situations, and business managers are really on their own to see trouble coming and react to it.

When first hit with poor results, some managers react like they touched a hot stove and quickly seek help to relieve the pain. These are the folks who have successful turnarounds, they are completely tuned in and run back to safety. Others go sailing off the cliff like Thelma and Louise. Some charge toward the cliff, teeth gritted, hands clenched, totally vapor‐locked in determination mode. No amount of information is going to overcome their stubbornness. Other debtors spin like a car sliding on ice toward the cliff peacefully oblivious to the situation. The difference in reaction magnifies quickly with time. One week later, the poor reaction is another week in trouble, whereas the wise reaction has enjoyed a week of recovery. In a month, the businesses can be worlds apart, one saveable and the other not.

Sociopaths often borrow money to start a business, leveraging many of their natural talents to do so. And when they end up in workout, all their ugliest traits come to the surface. A very thin sliver of entrepreneurs enjoyed success before going crazy and ending up institutionalized. They usually fall through my professional neighborhood on that journey.

Managers in Denial

I recently had a CEO who desperately wanted to “get it” and not be in denial. He felt so bad about having been an overbearing manager that, in a fit of democracy, he abdicated decision making to his management team. It was a nice instinct, but half the management team was incapable of thinking strategically and 100% were mostly concerned about protecting their own paychecks. This was like abdicating crop management to the locusts. So, they all voted to take my turnaround plan and execute it themselves, saving the company money and (more important) saving them from the sharp poke of me holding them accountable. In the first week, shipments were off 35%, but they just shrugged their shoulders. By the fifth week the company was out of money and I was called in to perform CPR. In the ninth week my emergency sale fell through, the business was immediately shut down, and all the jobs were lost.

You're No McKinsey Consultant

Several years ago a regional bank asked us to go visit one of their customers; it was the new owner of a $20 million business who had lost over $1.5 million in his first year. A quick Google search told me that the new entrepreneur had previously run two different $1 billion revenue companies with great success. He had a blue chip corporate career and had semiretired into entrepreneurship. We arrived at his business where he immediately started the lecture about how he knew what he was doing, the bank was all wrong, and he was a corporate thoroughbred if there ever was one. “I've run two different billion‐dollar businesses, I produced hundreds of millions of dollars in shareholder value, I've received awards, I'm a leader in this industry,” and he continued on about how his qualifications should eclipse his recent losses (if not the sun). “I've worked with plenty of consultants before, I've worked with McKinsey consultants in multiple projects and you're no McKinsey consultants, now are you?” he asked point blank, almost like poking his finger in my ribs. “No,” I replied slowly, “we're definitely not McKinsey consultants. We're just the guys the bank sends in before they liquidate a business.” A beautiful silence filled the air before he shifted the conversation to a more productive tone.

But he's right; turnaround folks are not your typical management consultants. In fact, I could never stomach the slow pace, theoretical nature of the work, the blah‐blah‐blah of it all would make me ill. Turnaround professionals are rarely consultants because they never aspired to be consultants, they are roll up your sleeves and get dirty‐type fixers who prefer to move on to the next hot mess.

Your CPA

So many small bankrupt businesses have well‐prepared tax returns and a very proud certified public accountant (CPA) standing behind them. Every year the telltale financials of these failing businesses pass through the hands of CPAs who dutifully prepares the tax return and does not mention the obvious distress. Or, business owners are cheap and they're not paying enough to get professional advice. Either way, the CPA firm you are working with must be scrutinized for the turnaround campaign. I've seen manufacturing companies that aren't measuring gross profit margin (the single most important number in manufacturing) because, “that's the way our accountant set it up.” So, neither the CEO nor the CPA understands the business, but one of them will have signed a personal guarantee for this adventure.

Although you can trust your cardiologist with your heart or your legal issues with your lawyer, you absolutely cannot trust the numbers of your business to anyone. Ever. It's your airplane, you are the pilot, this is your control panel, and you must fly the plane with those controls. It's the only hope you have to overcome the long‐odds of entrepreneurship.

Good CPAs will coach and guide the entrepreneur through cost containment and reduction strategies with some obvious advice about growing sales. This low‐level intervention will keep many businesses out of the ditch and give the CEO time to develop into the position. Great CPAs will do your tax and audit/review work just fine and will provide solid, basic advice similar to what you would expect from a CFO.

The Turnaround Process

Like most things in life and business, there is a process here with turnarounds. It starts with stabilization, then generates cash to fund changes in the business. The following steps summarize the outline and chapters of this book. True success in a turnaround follows an arc from crisis to stabilization, restructuring and then new growth and security. We'll explore these much more in the coming chapters.

- Stabilizing. After the initial shock,

we need to quickly assess the business for the biggest and most

fatal wounds and apply pressure. If your biggest customer just

pulled their business, you must be in their office the next day,

going for broke to get them back. If you've got a regulator issue,

you've got to contain it and manage the information to customers.

When your lender is upset, they generally want four things: (1)

respect, (2) attention, (3) collateral control, and (4)

information. Like the vacationing neighbor who owes you money, the

lender wants to see you worried more about its money than your

lifestyle. Our goal is getting 30 days of leniency, so

we can address all the issues and start a plan of remedy. This is

called forbearance, during which creditors agree to forbear (defer)

their right to put you out of business. There is formal forbearance

during which, say, your lender will agree not to

foreclose on your assets based on certain promises and fees. But in

a crisis, we don't have time for a formal forbearance, we just need

time to get things sorted out while trying try to save the

business. Emergency lender negotiations are continuous and often

sound something like this:

Mrs. Lender, as much as we respect your right to do X, Y, and Z, we believe that would be destructive and fraught with litigation concerns. Instead we ask that you retain all power and all options but give us a mere 30 days to present you with a complete turnaround plan to address these issues and increase the odds that you get paid back …

If you still have credibility left, that's about all you've got when making that pitch. I've turned 24‐hour reprieves into full months but on day one I'll take whatever we can get.

- Overreacting. It doesn't happen, so don't worry about it. I have yet to see an entrepreneur overcut costs or overraise prices. It's such an uncomfortable task that no one is overdoing it, but they all fear they are.

- Creating cash. Running a business on cash is the most familiar concept to a street merchant or hustler and the most foreign concept to a MBA or CFO. It's like running your lemonade stand out of your pocket, cash goes in and cash goes out and when you have no cash then you are broke. Creating cash is simply pulling cash off your balance sheet and the balance sheets of your customers and vendors. This cash funds the turnaround and protects value for all your stakeholders.

- Diagnosis. Now we're looking at the income statement (profit and loss statement or P&L) to figure out where the structural problems are in the business. The first question we need to answer is where the biggest cash drains are and make them smaller – pretty simple really. The problems are easy to identify when you've been in enough businesses and industries. Declining sales are an obvious problem. My second question is what the GPM (gross profit margin) is and then benchmark that against what we know of the industry and business model. Low GPM means the company's either not charging enough or is very inefficient in what it makes or provides. If the former, they probably have a timid sales department. If the latter, they have either not reinvested in production technology or they have a weak production culture. The third question is overhead (if my GPM is solid, what's eating up the profits?). The biggest categories are going to be labor, insurances, facilities, interest. They probably all need work, but figure out which are the biggest holes.

- Reorganizing. Once you're able to stabilize revenue, how much of a business can that revenue level actually support? If revenues were sawed in half, how do you adapt and reorganize your business around that new paradigm? (Hint: hoping for revenues to bounce back is not an option.) If you don't know what revenue is going to be, make a conservative guess and build a plan to be profitable around that. This is not a budgeting exercise, it's about forecasting cash flows and finding ways to stay cash positive throughout. It is not always pretty.

- The turnaround plan. This is the plan that you sell to the lenders, vendors, employees, key customers, and so on. Let me be clear, you are not presenting this plan, you are selling it. It has to be better than a liquidation and be simple to understand; we're cutting costs here and raising prices there. The turnaround plan should be complete and presentable as a draft within 30 days of formal turnaround work beginning. The turnaround plan details what's working and what's not in the business, what activities/products/investments will be grown, which ones will be fixed, and which ones exited. The expectation is that the business will become accrual‐based profitable the month the turnaround plan is enacted. When you can bring stakeholders a plan that requires no additional cash and fixes the business in 30 days, it's hard not to get support. This plan may include a shared sacrifice program between employees, customers, vendors, and lenders but the key is identifying and detailing how the company can stay open.

- Executing the turnaround. With a good plan and support of your creditors, now you can start to execute. Best to move quickly and do as much as you can all at once. If your plan calls for mass layoffs, closed divisions, higher prices, and so on – do it all at once. Shock the system then focus on recovery. This is ripping all the bandages off at once. Your employees have been through enough, don't drain their psyche with the slow drip‐drip of change. Once the band aids are off, focus on rebuilding confidence and morale, this is your team and you're still trying to get them to the Super Bowl. (See Chapter 5.)

- Restructure your debts around the new business. You need to show creditors how the business can survive, how it can regain health, and what level of debt it can repay over the next few years. Whether in or out of court, the process is similar. If the company has been crushed (i.e. lost half its revenues, needs to catch up on deferred capital investments, etc.) then it can only afford a certain amount of payments for principle and interest annually. Maybe all this requires is for the lenders to stretch out debts. Likely, they will need to take a principle haircut in addition to stretching out the repayment schedule. Accomplishing this is mostly psychological, if you're defaulting on corporate debt but still rolling up to the country club in your Maserati (like my client did) the lender will torture you. If you're like my father in his turnaround who sold his $200,000 Lexus, bought a VW and put the cash difference into the business, then the lender knows you respect its money, are committed to the process, and are working with them. (See Chapter 8.)

- Growing or selling the business when the turnaround is complete. Whew, breathe deep again, just like when you started this perilous journey. When I got to this point in our own turnaround, it was like the storm clouds had finally parted and the sun was poking through. Our revenues were growing, employees were smiling again, our new product‐development backlog was at an all‐time high, and we were prebooking orders at a record‐setting pace. Our balance sheet was still heavily levered but everything else was great. So I went on a long and remote vacation to celebrate, restore and get ready for our busy fall season. Then Hurricane Katrina rolled in and reset the clock.

A Word on Professional Help

I wish we had hired a turnaround consultant (also called a chief restructuring officer (CRO) or turnaround manager) after Katrina. My brains were scrambled and an objective, experienced advisor could have improved our outcome by several million dollars. Sometimes a turnaround professional is an insurance policy, someone who might double your odds of success going through a 90‐day transition with perilous risks. Turnaround consultants are hired gun advisors who rest up between assignments, so they can give their clients extraordinary levels of effort and attention when needed.

The best resource for identifying turnaround consultants is through the Turnaround Management Association, which administers the industry certification, called the Certified Turnaround Professional (CTP). Certification is earned through a series of exams, validated experience, peer and client reviews. The three exams cover

- Commercial, insolvency, and bankruptcy law.

- Accounting, financial analysis, cash forecasting, commercial finance, and valuation.

- Turnaround management and the ability to rapidly reshape an organization.

Applicants also must have led a certain number of verifiable turnarounds in their career and have interacted with enough other insolvency professionals to support their accomplishments with peer and client reviews. With equal amounts of law, finance, and management experience, turnaround experience often takes decades to develop. A recent check on the TMA roster showed there were 364 CTPs in the United States. Like all other professionals, you should screen them for a track record of results, reputation, industry experience, and personal chemistry.