1.

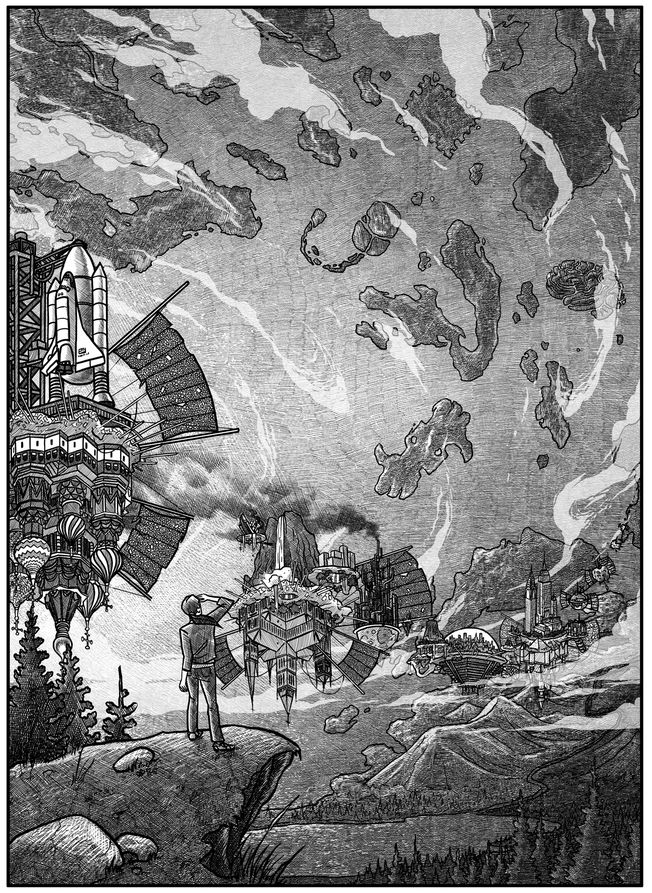

The BookWorld Remade

The remaking was one of those moments when one

felt a part of literature and not just carried along within it. In

less than ten minutes, the entire fabric of the BookWorld was

radically altered. The old system was swept away, and everything

was changed forever. But the group of people to whom it was

ultimately beneficial remained gloriously unaware: the readers. To

most of them, books were merely books. If only it were that simple.

. . .

Bradshaw’s BookWorld Companion (2nd

edition)

Everyone can remember where they

were when the BookWorld was remade. I was at home “resting between

readings,” which is a polite euphemism for “almost

remaindered.”

But I wasn’t doing nothing. No, I was using the

time to acquaint myself with EZ-Read’s latest Laborsaving Narrative

Devices, all designed to assist a first-person protagonist like me

cope with the strains of a sixty-eight-setting five-book series at

the speculative end of Fantasy.

I couldn’t afford any of these devices—not even

Verb-Ease™ for troublesome irregularity—but that wasn’t the point.

It was the company of EZ-Read’s regional salesman that I was

interested in, a cheery Designated Love Interest named Whitby

Jett.

“We have a new line in foreshadowing,” he said,

passing me a small blue vial.

“Does the bottle have to be in the shape of Lola

Vavoom?” I asked.

“It’s a marketing thing.”

I opened the stopper and sniffed at it

gingerly.

“What do you think?” he asked.

Whitby was a good-looking man described as a

youthful forty. I didn’t know it then, but he had a dark past, and

despite our mutual attraction his earlier misdeeds could only end

in one way: madness, recrimination and despair.

“I prefer my foreshadowing a little less pungent,”

I said, carefully replacing the stopper. “I was getting all sorts

of vibes about you and a dark past.”

“I wish,” replied Whitby sadly. His book had been

deleted long ago, so he was one of the many thousands of characters

who eked out a living in the BookWorld while they waited for a

decent part to come along. But because of his minor DLI character

status, he had never been given a backstory. Those without any sort

of history often tried to promote it as something mysterious when

it wasn’t, but not Whitby, who was refreshingly pragmatic. “Even

having no backstory as my backstory would be something,” he had

once told me in a private moment, “but the truth is this: My author

couldn’t be bothered to give me one.”

I always appreciated honesty, even as personal as

this. There weren’t many characters in the BookWorld who had been

left unscathed by the often selfish demands of their creators. A

clumsily written and unrealistic set of conflicting motivations can

have a character in therapy for decades—perhaps forever.

“Any work offers recently?” I asked.

“I was up for a minor walk-on in an Amis.”

“How did you do?”

“I read half a page and they asked me what I

thought. I said I understood every word and so was rejected as

being overqualified.”

“I’m sorry to hear that.”

“It’s okay,” he said. “I was also offered a

four-hundred-and-six-word part in a horror last week, but I’m not

so sure. First-time author and a small publisher, so I might not

make it past the second impression. If I get remaindered, I’d be

worse off than I am now.”

“I’m remaindered,” I reminded him.

“But you were once popular,” he said, “so

you might be again. Do you know how many characters have high hopes

of a permanent place in the readers’ hearts, only to suffer the

painful rejection of eternal unreadfulness at the dreary end of

Human Drama?”

He was right. A book’s life could be very long

indeed, and although the increased leisure time in an unread novel

is not to be sniffed at, a need to be vigilant in case someone

does read you can keep one effectively tied to a book for

life. I usually had an understudy to let me get away, but few were

so lucky.

“So,” said Whitby, “how would you like to come out

to the smellies tonight? I hear Garden Peas with Mint is

showing at the Rex.”

In the BookWorld, smells were in short supply.

Garden Peas with Mint had been the best release this year.

It only narrowly beat Vanilla Coffee and Grilled Smoked

Bacon for the prestigious Noscar™ Best Adapted Smell

award.

“I heard that Mint was overrated,” I

replied, although I hadn’t. Whitby had been asking me out for a

date almost as long as I’d been turning him down. I didn’t tell him

why, but he suspected that there was someone else. There was and

there wasn’t. It was complex, even by BookWorld standards. He asked

me out a lot, and I declined a lot. It was kind of like a

game.

“How about going to the Running of the Bumbles next

week? Dangerous, but exciting.”

This was an annual fixture on the BookWorld

calendar, where two dozen gruel-crazed and indignant Mr. Bumbles

yelling, “More? MORE?!?” were released to charge through an unused

chapter of Oliver Twist. Those of a sporting or daring

disposition were invited to run before them and take their chances;

at least one hapless youth was crushed to death every year.

“I’ve no need to prove myself,” I replied, “and

neither do you.”

“How about dinner?” he asked, unabashed. “I can get

a table at the Inn Uendo. The maîtred’ is missing a space, and I

promised to give her one.”

“Not really my thing.”

“Then what about the Bar Humbug? The atmosphere is

wonderfully dreary.”

It was over in Classics, but we could take a

cab.

“I’ll need an understudy to take over my

book.”

“What happened to Stacy?”

“The same as happened to Doris and Enid.”

“Trouble with Pickwick again?”

“As if you need to ask.”

And that was when the doorbell rang. This was

unusual, as random things rarely occur in the mostly predetermined

BookWorld. I opened the door to find three Dostoyevskivites staring

at me from within a dense cloud of moral relativism.

“May we come in?” said the first, who had the look

of someone weighed heavily down with the burden of conscience. “We

were on our way home from a redemption-through-suffering training

course. Something big’s going down at Text Grand Central, and

everyone’s been grounded until further notice.”

A grounding was rare, but not unheard of. In an

emergency all citizens of the BookWorld were expected to offer

hospitality to those stranded outside their books.

I might have minded, but these guys were from

Crime and Punishment and, better still, celebrities. We

hadn’t seen anyone famous this end of Fantasy since Pamela from

Pamela stopped outside with a flat tire. She could have been

gone in an hour but insisted on using an epistolary breakdown

service, and we had to put her up in the spare room while a complex

series of letters went backwards and forwards.

“Welcome to my home, Rodion Romanovich

Raskolnikov.”

“Oh!” said Raskolnikov, impressed that I knew who

he was. “How did you know it was me? Could it have been the subtle

way in which I project the dubious moral notion that murder might

somehow be rationalized, or was it the way in which I move from

denying my guilt to eventually coming to terms with an absolute

sense of justice and submitting myself to the rule of law?”

“Neither,” I said. “It’s because you’re holding an

ax covered in blood and human hair.”

“Yes, it is a bit of a giveaway,” he admitted,

staring at the ax, “but how rude am I? Allow me to introduce Arkady

Ivanovich Svidrigailov.”

“Actually,” said the second man, leaning over to

shake my hand, “I’m Dmitri Prokofich Razumikhin, Raskolnikov’s

loyal friend.”

“You are?” said Raskolnikov in surprise. “Then what

happened to Svidrigailov?”

“He’s busy chatting up your sister.”

He narrowed his eyes.

“My sister? That’s Pulcheria Alexandrovna

Raskolnikova, right?”

“No,” said Razumikhin in the tone of a

long-suffering best friend, “that’s your mother. Avdotya Romanovna

Raskolnikova is your sister.”

“I always get those two mixed up. So who’s Marfa

Petrovna Svidrigailova?”

Razumikhin frowned and thought for a moment.

“You’ve got me there.”

He turned to the third Russian.

“Tell me, Pyotr Petrovich Luzhin: Who, precisely,

is Marfa Petrovna Svidrigailova?”

“I’m sorry,” said the third Russian, who had been

staring at her shoes absently, “but I think there has been some

kind of mistake. I’m not Pyotr Petrovich Luzhin. I’m Alyona

Ivanovna.”

Razumikhin turned to Raskolnikov and lowered his

voice.

“Is that your landlady’s servant, the one who

decides to marry down to secure her future, or the one who turns to

prostitution in order to stop her family from descending into

penury?”

Raskolnikov shrugged. “Listen,” he said, “I’ve been

in this book for over a hundred and forty years, and even I can’t

figure it out.”

“It’s very simple,” said the third Russian,

indicating who did what on her fingers. “Nastasya Petrovna is

Raskolnikov’s landlady’s servant, Avdotya Romanovna Raskolnikova is

your sister who threatens to marry down, Sofia Semyonovna

Marmeladova is the one who becomes a prostitute, and Marfa Petrovna

Svidrigailova—the one you were first asking about—is Arkady

Svidrigailov’s murdered first wife.”

“I knew that,” said Raskolnikov in the manner of

someone who didn’t. “So . . . who are you again?”

“I’m Alyona Ivanovna,” said the third Russian with

a trace of annoyance, “the rapacious old pawnbroker whose apparent

greed and wealth led you to murder.”

“Are you sure you’re Ivanovna?” asked

Raskolnikov with a worried tone.

“Absolutely.”

“And you’re still alive?”

“So it seems.”

He stared at the bloody ax. “Then who did I just

kill?”

And they all looked at one another in

confusion.

“Listen,” I said, “I’m sure everything will come

out fine in the epilogue. But for the moment your home is my

home.”

Anyone from Classics had a celebrity status that

outshone anything else, and I’d never had anyone even remotely

famous pass through before. I suddenly felt a bit hot and bothered

and tried to tidy up the house in a clumsy sort of way. I whipped

my socks from the radiator and brushed off the pistachio shells

that Pickwick had left on the sideboard.

“This is Whitby Jett of EZ-Read,” I said,

introducing the Russians one by one but getting their names

hopelessly mixed up, which might have been embarrassing had they

noticed. Whitby shook all their hands and then asked for

autographs, which I found faintly embarrassing.

“So why has Text Grand Central ordered a

grounding?” I asked as soon as everyone was seated and I had rung

for Mrs. Malaprop to bring in the tea.

“I think the rebuilding of the BookWorld is about

to take place,” said Razumikhin with a dramatic flourish.

“So soon?”

The remaking had been a hot topic for a number of

years. After Imagination™ was deregulated in the early fifties, the

outburst of creative alternatives generated huge difficulties for

the Council of Genres, who needed a clearer overview of how the

individual novels sat within the BookWorld as a whole. Taking the

RealWorld as inspiration, the CofG decided that a Geographic model

was the way to go. How the physical world actually appeared, no one

really knew. Not many people traveled to the RealWorld, and those

who did generally noted two things: one, that it was hysterically

funny and hideously tragic in almost equal measure, and two, that

there were far more domestic cats than baobabs, when it should

probably be the other way round.

Whitby got up and looked out the window. There was

nothing to see, quite naturally, as the area between books

had no precise definition or meaning. My front door opened to,

well, not very much at all. Stray too far from the boundaries of a

book and you’d be lost forever in the interbook Nothing. It was

confusing, but then so were Tristram Shandy, The

Magus and Russian novels, and people had been enjoying them for

decades.

“So what’s going to happen?” asked Whitby.

“I have a good friend over at Text Grand Central,”

said Alyona Ivanovna, who had wisely decided to sit as far from

Raskolnikov and the bloody ax as she could, “and he said that to

accomplish a smooth transition from Great Library BookWorld to

Geographic BookWorld, the best option was to close down all the

imaginotransference engines while they rebooted the throughput

conduits.”

This was an astonishing suggestion. The

imaginotransference engines were the machines that transmitted the

books in all their subtle glory from the BookWorld to the reader’s

imagination. To shut them down meant that reading—all

reading—had to stop. I exchanged a nervous glance with

Whitby.

“You mean the Council of Genres is going to shut

down the entire BookWorld?”

Alyona Ivanovna nodded. “It was either that or do

it piecemeal, which wasn’t favored, since then half the BookWorld

would be operating one system and half the other. It’s simple: All

reading needs to stop for the nine minutes it requires to have the

BookWorld remade.”

“But that’s insane!” exclaimed Whitby. “People will

notice. There’s always someone reading somewhere.”

From my own failed experience of joining the

BookWorld’s policing agency, I knew that he spoke the truth. There

was a device hung high on the wall in the Council of Genres

debating chamber that logged the Outland ReadRate—the total number

of readers at any one time. It bobbed up and down but rarely

dropped below the 20-million mark. But while spikes in reading were

easier to predict, such as when a new blockbuster is published or

when an author dies—always a happy time for their creations, if not

their relatives—predicting slumps was much harder. And we needed a

serious slump in reading to get down to the under-fifty-thousand

threshold considered safe for a remaking.

I had an idea. I fetched that morning’s copy of

The Word and turned to the week’s forecast. This wasn’t to

do with weather, naturally, but trends in reading. Urban Vampires

were once more heavily forecast for the week ahead, with scattered

Wizards moving in from Wednesday and a high chance of Daphne

Farquitt Novels near the end of the week. There was also an alert

for everyone at Sports Trivia to “brace themselves,” and it stated

the reason.

“There you go,” I said, tapping the newspaper and

showing it to the assembled company. “Right about now the Swindon

Mallets are about to defend their title against the Gloucester

Meteors, and with live televised coverage to the entire planet

there is a huge potential fall in the ReadRate.”

“You think that many people are interested in

Premier League croquet?” asked Razumikhin.

“It is Swindon versus Gloucester,” I

replied, “and after the Malletts’ forward hoop, Penelope Hrah,

exploded on the forty-yard line last year, I would expect

ninety-two percent of the world will be watching the game—as good a

time as any to take the BookWorld offline.”

“Did they ever find out why Hrah exploded?”

asked Whitby.

“It was never fully explained,” put in Ivanovna,

“but traces of Semtex were discovered in her shin guards, so foul

play could never be ruled out entirely. A grudge match is always a

lot of fu—”

Her voice was abruptly cut dead, but not in the way

one’s is when one has suddenly stopped speaking. Her voice was

clipped, like a gap in a recording.

“Hello?” I said.

The three Russians made no answer and were simply

staring into space, like mannequins. After a moment they started to

lose facial definition as they became a series of complex irregular

polyhedra. After a while the number of facets of the polyhedra

started to lessen, and the Russians became less like people and

more like jagged, flesh-colored lumps. Pretty soon they were

nothing at all. The Classics were being shut down, and if Text

Grand Central was doing it alphabetically, Fantasy would not be far

behind. And so it proved. I looked at Whitby, who gave me a wan

smile and held my hand. The room grew cold, then dark, and before

long the only world that I knew started to disassemble in front of

my eyes. Everything grew flatter and lost its form, and pretty soon

I began to feel my memory fade. And just when I was starting to

worry, everything was cleansed to an all-consuming darkness.

#shutting down imaginotransference engines,

46,802

readers

#active reader states have been cached

#dismounting READ OS 8.3.6

#start programs

#check and mount specified dictionaries

#check and mount specified thesauri

#check and mount specified idiomatic database

#check and mount specified grammatical database

#check and mount specified character database

#check and mount specified settings database

Mount temporary ISBN/BISAC/duodecimal book category

system

Mount imaginotransference throughput module

Accessing “book index” on global bus

Creating cache for primary plot-development module

Creating /ramdisk in “story interpretation,”

default size=300

Creating directories: irony

Creating directories: humor

Creating directories: plot

Creating directories: character

Creating directories: atmosphere

Creating directories: prose

Creating directories: pace

Creating directories: pathos

Starting init process

#display imaginotransference-engine error messages

#recovering active readers from cache

System message=Welcome to Geographic Operating

System 1.2

Setting control terminal to automatic

System active with 46,802 active readers

readers

#active reader states have been cached

#dismounting READ OS 8.3.6

#start programs

#check and mount specified dictionaries

#check and mount specified thesauri

#check and mount specified idiomatic database

#check and mount specified grammatical database

#check and mount specified character database

#check and mount specified settings database

Mount temporary ISBN/BISAC/duodecimal book category

system

Mount imaginotransference throughput module

Accessing “book index” on global bus

Creating cache for primary plot-development module

Creating /ramdisk in “story interpretation,”

default size=300

Creating directories: irony

Creating directories: humor

Creating directories: plot

Creating directories: character

Creating directories: atmosphere

Creating directories: prose

Creating directories: pace

Creating directories: pathos

Starting init process

#display imaginotransference-engine error messages

#recovering active readers from cache

System message=Welcome to Geographic Operating

System 1.2

Setting control terminal to automatic

System active with 46,802 active readers

“Thursday?”

I opened my eyes and blinked. I was lying on the

sofa staring up at Whitby, who had a concerned expression on his

face.

“Are you okay?”

I sat up and rubbed my head. “How long was I

out?”

“Eleven minutes,”

I looked around. “And the Russians?”

“Outside.”

“There is no outside.”

He smiled. “There is now. Come and have a

look.”

I stood up and noticed for the first time that my

living room seemed that little bit more realistic. The colors were

subtler, and the walls had an increased level of texture. More

interestingly, the room seemed to be brighter, and there was light

coming in through the windows. It was real light, too, the

sort that casts shadows and not the pretend stuff we were used to.

I grasped the handle, opened the front door and stepped

outside.

The empty interbook Nothing that had separated the

novels and genres had been replaced by fields, hills, rivers, trees

and forests, and all around me the countryside opened out into a

series of expansive vistas with the welcome novelty of

distance. We were now in the southeast corner of an island

perhaps a hundred miles by fifty and bounded on all sides by the

Text Sea, which had been elevated to “Grade IV Picturesque” status

by the addition of an azure hue and a soft, billowing motion that

made the text shimmer in the breeze.

As I looked around, I realized that whoever had

remade the BookWorld had considered practicalities as much as

aesthetics. Unlike the RealWorld, which is inconveniently located

on the outside of a sphere, the new BookWorld was anchored

on the inside of a sphere, thus ensuring that horizons

worked in the opposite way to those in RealWorld. Farther objects

were higher in the visual plane than nearer ones. From anywhere in

the BookWorld, it was possible to view anywhere else. I noticed,

too, that we were not alone. Stuck on the inside of the sphere were

hundreds of other islands very similar to our own, and each a haven

for a category of literature therein.

About ten degrees upslope of Fiction, I could see

our nearest neighbor: Artistic Criticism. It was an exceptionally

beautiful island, yet deeply troubled, confused and suffused with a

blanketing layer of almost impenetrable bullshit. Beyond that were

Psychology, Philately, and Software Manuals. But the brightest and

biggest archipelago I could see upon the closed sea was the

scattered group of genres that made up Nonfiction. They were

positioned right on the other side of the inner globe and so were

almost directly overhead. On one side of the island the Cliffs of

Irrationality were slowly being eroded away, while on the opposite

shore the Sands of Science were slowly reclaiming salt marsh from

the sea.

While I stared upwards, openmouthed, a steady

stream of books moved in an endless multilayered crisscross high in

the sky. But these weren’t books of the small paper-and-leather

variety that one might find in the Outland. These were the

collected settings of the book all bolted together and

connected by a series of walkways and supporting beams, cables and

struts. They didn’t look so much like books, in fact, but more like

a series of spiky lumps. While some one-room dramas were no bigger

than a double-decker bus and zipped across the sky, others moved

slowly enough for us to wave at the occupants, who waved back. As

we stood watching our new world, the master copy of Doctor

Zhivago passed overhead, blotting out the light and covering us

in a light dusting of snow.

“O brave new world, that has such stories

in’t!”

“What do you think?” asked Whitby.

“O brave new world,” I whispered as I gave him a

hug, “that has such stories in’t!”