A Train Bound for

Glory

“Frankly, from the way I have been treated by the so-called ‘civilized’ people in my life, I rather look forward to residency among the savages.”(from the journals of May Dodd)

[NOTE: The following entry, undated,

appears on the first page of the first notebook of May Dodd’s

journal.]

I leave this record for my dear children, Hortense and William, in the event that they never see their loving mother again and so that they might one day know the truth of my unjust incarceration, my escape from Hell, and into whatever is to come in these pages …

Today is my birthday, and I have

received the greatest gift of all—freedom! I make these first poor

scribblings aboard the westbound Union Pacific train which departed

Union Station Chicago at 6:35 a.m. this morning, bound for Nebraska

Territory. We are told that it will be a fourteen-day trip with

many stops along the way, and with a change of trains in Omaha.

Although our final destination was intended to have been concealed

from us, I have ascertained from overhearing conversations among

our military escort (they underestimate a woman’s auditory powers)

that we are being taken first to Fort Sidney aboard the train—from

there transported by wagon train to Fort Laramie, Wyoming

Territory, and then on to Camp Robinson, Nebraska

Territory.

How strange is life. To think that I

would find myself on this train, embarking upon this long journey,

watching the city retreating behind me. I sit facing backwards on

the train in order to have a last glimpse of Chicago, the layer of

dense black coal smoke that daily creeps out over the beach of Lake

Michigan like a giant parasol, the muddy, bustling city passing by

me for the last time. How I have missed this loud, raucous city

since my dark and silent incarceration. And now I feel like a

character in a theater play, torn from the real world, acting out

some terrible and as yet unwritten role. How I envy these people I

watch from the train window, hurrying off to the safety of their

daily travails while we are borne off, captives of fate into the

great unknown void.

Now we pass the new shanties that ring

the city, that have sprung up everywhere since the great fire of

’71. Little more than cobbled-together scraps of lumber they teeter

in the wind like houses of cards, to form a kind of rickety fence

around the perimeters of Chicago—as if somehow trying to contain

the sprawling metropolis. Filthy half-dressed children play in

muddy yards and stare blankly at us as we pass, as if we, or

perhaps they, are creatures from some other world. How I long for

my own dear children! What I would give to see them one last time,

to hold them … now I press my hand against the train window to wave

to one tiny child who reminds me somehow of my own sweet son

William, but this poor child’s hair is fair and greasy, hanging in

dirty ringlets around his mud-streaked face. His eyes are intensely

blue and he raises his tiny hand tentatively as we pass to return

my greeting … I should say my farewell … I watch him growing

smaller and smaller and then we leave these last poor outposts

behind as the eastern sun illuminates the retreating city—the stage

fades smaller and smaller into the distance. I watch as long as I

can and only then do I finally gain the courage to change seats, to

give up my dark and troubled past and turn around to face an

uncertain and terrifying future. And when I do so the breath

catches in my throat at the immensity of earth that lies before us,

the prairie unspeakable in its vast, lonely reaches. Dizzy and

faint at the sight of it, I feel as if the air has been sucked from

my lungs, as if I have fallen off the edge of the world, and am

hurtling headlong through empty space. And perhaps I have … perhaps

I am …

But dear God, forgive me, I shall never again utter a complaint, I shall always remind myself how wonderful it is to be free, how I prayed for this moment every day of my life, and my prayers are answered! The terror in my heart of what lies ahead seems of little consequence compared with the prospect of spending my lifetime as an “inmate” in that loathsome “prison”—for it was a prison far more than a hospital, we were prisoners rather than patients. Our “medical treatment” consisted of being held captive behind iron bars, like animals in the zoo, ignored by indifferent doctors, tortured, taunted, and assaulted by sadistic attendants.

My definition of LUNATIC ASYLUM: A

place where lunatics are created.

“Why am I here?” I asked Dr. Kaiser,

when he first came to see me, fully a fortnight after my

“admittance.”

“Why, due to your promiscuous

behavior,” he answered as if genuinely surprised that I dare to

even pose such a query.

“But I am in love!” I protested, and

then I told him about Harry Ames. “My family placed me here because

I left home to live out of wedlock with a man whom they considered

to be beneath my station. For no better reason than that. When they

could not convince me to leave him, they tore me from him, and from

my babies. Can you not see, Doctor, that I’m no more insane than

you?”

Then the doctor raised his eyebrows

and scribbled on his notepad, nodding with an infuriating air of

sanctimony. “Ah,” he said, “I see—you believe that you were sent

here as part of a conspiracy among your family.” And he rose and

left me and I did not see him again for nearly six

months.

During this initial period I was

subject to excruciating “treatments” prescribed by the good doctor

to cure me of my “illness.” These consisted of daily injections of

scalding water into my vagina—evidently intended to calm my

deranged sexual desires. At the same time, I was confined to my bed

for weeks on end—forbidden from fraternizing with the other

patients, not allowed to read, write letters, or pursue any other

diversion. The nurses and attendants did not speak to me, as if I

did not exist. I endured the further humiliation of being forced to

use a bedpan, although there was nothing whatsoever physically

wrong with me. Were I to protest or if I was found by a nurse out

of my bed, I would be strapped into it for the remainder of the day

and night.

It was during this period of

confinement that I truly lost my mind. If the daily torture weren’t

enough, the complete isolation and inactivity were in themselves

insupportable. I longed for fresh air and exercise, to promenade

along Lake Michigan as I once had … At great risk I would steal

from my bed before dawn and stand on a chair in my room, straining

to see out through the iron bars that covered the tiny shaded

window—just to catch one glimpse of daylight, one patch of green

grass on the lawn outside. I wept bitterly at my fate, but I

struggled against the tears, willed them away. For I had also

learned that I must not allow anyone on staff to see me weep, lest

it be said in addition to the doctor’s absurd diagnosis of

promiscuity, that I was also victim of Hysteria or Melancholia …

which would only be cause for further tortures.

Let me here set down, once and for

ever, the true circumstances of my incarceration.

Four years ago I fell in love with a

man named Harry Ames. Harry was several years my senior and foreman

of Father’s grain-elevator operations. We met at my parents’ home,

where Harry came regularly to consult with Father on business

matters. Harry is a very attractive man, if somewhat rough around

the edges, with strong masculine arms and a certain workingman’s

self-confidence. He was nothing like the insipid, privileged boys

with whom girls of my station are reduced to socializing at tea and

cotillion. Indeed, I was quite swept away by Harry’s charms … one

thing led to another … yes well, surely by the standards of some I

might be called promiscuous.

I am not ashamed to admit that I have

always been a woman of passionate emotions and powerful physical

desires. I do not deny them. I came to full flower at an early age,

and had always quite intimidated the awkward young men of my

family’s narrow social circle.

Harry was different. He was a man; I

was drawn to him like a moth to flame. We began to see each other

secretly. Both of us knew that Father would never condone our

relationship and Harry was as anxious about being found out as

I—for he knew that it would cost him his job. But we could not

resist one another—we could not stay apart.

The very first time I lay with Harry I

became with child—my daughter Hortense. Truly, I felt her burst

into being in my womb in the consummation of our love. I must say,

Harry behaved like a gentleman, and assumed full responsibility. He

offered to marry me, which I flatly refused, for although I loved

him, and still do, I am an independent, some might say, an

unconventional woman. I was not prepared to marry. I would not,

however, give up my child, and so without explanation I moved out

of my parents’ home and took up residence with my beloved in a

shabby little house on the banks of the Chicago River, where we

lived very simply and happily for a time.

Naturally, it was not long before

Father learned about his foreman’s deception, and promptly

dismissed him. But Harry soon found work with one of Father’s

competitors and I, too, found employment. I went to work in a

factory that processed prairie chickens for the Chicago market. It

was filthy, exhausting work, for which my privileged upbringing had

in no way prepared me. At the same time, and perhaps for the same

reason, it was oddly liberating to be out in the real world, and

making my own way there.

I gave birth to Hortense and almost

immediately became pregnant again with my son William … sweet

Willie. I tried to maintain contact with my parents—I wished them

to know their grandchildren, and not to judge me too harshly for

having chosen a different path for myself. But Mother was largely

hysterical whenever I arranged to visit her—indeed, it is she,

perhaps, who should have been institutionalized, not I—and Father

was inflexible and refused to even see me when I came to the house.

I finally stopped going there altogether, and kept up only a

tenuous contact with the family through my older married sister,

also named Hortense.

By the time I gave birth to Willie,

Harry and I had begun to have some difficulties. I wonder now if

Father’s agents were already working on him, even then, for he

seemed to change almost overnight, to become distant and remote. He

began to drink and to stay out all night, and when he came home I

could smell the other women on him. It broke my heart, for I still

loved him. Still, I was more than ever glad that I had not married

him.

It was on one such night when Harry

was away that Father’s blackguards came. They burst through the

door of our house in the middle of the night accompanied by a

nurse, who snatched up my babies and spirited them away as the men

restrained me. I fought them for all I was worth—screaming,

kicking, biting, and scratching, but, of course, to no avail. I

have not seen my children since that dark night.

I was taken directly to the lunatic

asylum, where I was consigned to lie in bed in my darkened room,

day after day, week after week, month after month, with nothing to

occupy my time but my daily torture and constant thoughts of my

babies—I had no doubt they were living with Father and Mother. I

did not know what had become of Harry and was haunted by thoughts

of him … (Harry, my Harry, love of my life, father of my children,

did Father reward you with pieces of gold to give me up to his

ruffians in the middle of the night? Did you sell your own babies

to him? Or did he simply have you murdered? Perhaps I shall never

know the truth … )

All of my misery for the crime of

falling in love with a common man. All of my heartbreak, torture,

and punishment because I chose to bring you, my dearest children,

into the world. All of my black and hopeless despair because I

chose an unconventional life …

Ah, but surely nothing that has come

before can be considered unconventional in light of where I am now

going! Let me record the exact events that led me to be on this

train: Two weeks ago, a man and a woman came into the ladies

dayroom at the asylum. Owing to the nature of my “affliction” —my

“moral perversion,” as it was described in my commitment papers (a

sham and a travesty—how many other women I wonder have been locked

away like this for no just cause!), I was among those patients

strictly segregated by gender, prohibited even from fraternizing

with members of the opposite sex—presumably for fear that I might

try to copulate with them. Good God! On the other hand, my

diagnosis seemed to be considered an open invitation to certain

male members of the asylum staff to visit my room in the middle of

the night. How many times did I wake up, as if suffocating, with

the weight of one particularly loathsome attendant named Franz

pressed upon me, a fat stinking German, corpulent and sweating …

God help me, I prayed to kill him.

The man and woman looked us over

appraisingly as if we were cattle auction, and then they chose six

or seven among us to come with them to a private staff room.

Conspicuously absent from this group were any of the older women or

any of the hopelessly, irredeemably insane—those who sit rocking

and moaning for hours on end, or who weep incessantly or hold

querulous conversations with their demons. No, these poor afflicted

were passed over and the more “presentable” of us lunatics chosen

for an audience with our visitors.

After we had retired to the private

staff room, the gentleman, a Mr. Benton, explained that he was

interviewing potential recruits for a government program that

involved the Indians of the Western plains. The woman, who he

introduced as Nurse Crowley, would, with our consent, perform a

physical examination upon us. Should we be judged, based on the

interview and examination, to be suitable candidates for the

program, we might be eligible for immediate release from this

hospital. Yes! Naturally, I was intrigued by the proposal. Yet

there was a further condition of family consent, which I had scant

hope of ever obtaining.

Still I volunteered my full

cooperation. Truly, even an interview and a physical examination

seemed preferable to the endless hours of agonizing monotony spent

sitting or lying in bed, with nothing to pass the time besides

foreboding thoughts about the injustice of my sentence and the

devastating loss of my babies—the utter hopelessness of my

situation and the awful anticipation of my next

“treatment.”

“Did I have any reason to believe that

I was not fruitful?”—this was the first question posed to me by

Nurse Crowley at the beginning of her examination. I must say I was

taken aback—but I answered promptly, already having set my mind to

passing this test, whatever its purpose. “Au contraire!” I said, and I told the nurse

of the two precious children I had already borne out of wedlock,

the son and daughter, who were so cruelly torn from their mother’s

bosom.

“Indeed,” I said, “so fruitful am I

that if my beloved Harry Ames, Esq., simply gazed upon me with a

certain romantic longing in his eyes, babes sprang from my loins

like seed spilling from a grain sack!”

(I must mention the unmentionable: the

sole reason I did not become with child by the repulsive attendant

Franz, the monster who visited me by night, is that the pathetic

cretin sprayed his revolting discharge on my bedcovers, humping and

moaning and weeping bitterly in his premature

agonies.)

I feared that I may have gone too far

in my enthusiasm to impress Nurse Crowley with my fertility, for

she looked at me with that tedious and by now all too familiar

expression of guardedness with which people regard the insane—and

the alleged insane alike—as if our maladies might be

contagious.

But apparently I passed my initial

examination, for next I was interviewed by Mr. Benton himself, who

also asked me a series of distinctly queer questions: Did I know

how to cook over a campfire? Did I enjoy spending time outdoors?

Did I enjoy sleeping out overnight? What was my personal estimation

of the western savage?

“The western savage?” I interrupted.

“Having never met any western savages, Sir, it would be difficult

for me to have formed any estimation of them one way or

another.”

Finally Mr. Benton got down to the

business at hand: “Would you be willing to make a great personal

sacrifice in the service of your government?” he

asked.

“But of course,” I answered without

hesitation.

“Would you consider an arranged

marriage to a western savage for the express purpose of bearing a

child with him?”

“Hah!” I barked a laugh of utter

astonishment. “But why on earth?” I asked, more curious than

offended. “For what purpose?”

“To ensure a lasting peace on the

Great Plains,” Mr. Benton answered. “To provide safe passage to our

courageous settlers from the constant depredations of the

bloodthirsty barbarians.”

“I see,” I said, but of course, I did

not altogether.

“As part of our agreement,” added Mr.

Benton, “your President will demonstrate his eternal gratitude to

you by arranging for your immediate release from this

institution.”

“Truly? I would be released from this

place?” I asked, trying to conceal the trembling in my

voice.

“That is absolutely guaranteed,” he

said, “assuming that your legal guardian, if such exists, is

willing to sign the necessary consent forms.”

Already I was formulating my plan for

this last major hurdle to my freedom, and again I answered without

a moment’s hesitation. I stood and curtsied deeply, weak in the

knees, both from my months of idle confinement and pure excitement

at the prospect of freedom: “I should be deeply honored, Sir, to

perform this noble duty for my country,” I said, “to offer my

humble services to the President of the United States.” The truth

is that I would have gladly signed on for a trip to Hell to escape

the lunatic asylum … and, yet, perhaps that is exactly what I have

done …

As to the critical matter of obtaining

my parents’ consent, let me say in preface, that although I may

have been accused of insanity and promiscuity, no one has ever

taken me for an idiot.

It was the responsibility of the

hospital’s chief physician, my own preposterous diagnostician, Dr.

Sidney Kaiser, to notify the families of those patients under

consideration for the BFI program (these initials stand for “Brides

for Indians” as Mr. Benton explained to us) and invite them to the

hospital to be informed of the program and to obtain their

signatures on the necessary release papers—at which time the

patients would be free to participate in the program if they so

chose. In the year and a half that I had been incarcerated there

against my will, I had, as I may have mentioned, been visited only

twice by the good doctor. However, through my repeated but futile

efforts to obtain an audience with him, I had become acquainted

with his assistant, Martha Atwood, a fine woman who took pity on

me, who befriended me. Indeed, Martha became my sole friend and

confidante in that wretched place. Without her sympathy and visits,

and the many small kindnesses she bestowed upon me, I do not know

how I could have survived.

As we came to know one another, Martha

was more than ever convinced that I did not belong in the asylum,

that I was no more insane than she, and that, like other women

there, I had been committed unjustly by my family. When this

opportunity presented itself for me to “escape,” she agreed to help

me in my desperate plan. First she “borrowed” correspondence from

Father out of my file in Dr. Kaiser’s office, and she had made a

duplicate of his personal letterhead. Together we forged a letter

in Father’s hand, written to Dr. Kaiser, in which Father explained

that he was traveling on business and would be unable to attend the

proposed meeting at the institution. Dr. Kaiser would have no

reason to question this; he was aware of Father’s position as

president of the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad, for which

Father had designed and built the entire grain-elevator system—the

largest and most advanced such warehouse in the city, as he is

forever reminding us. Father’s job involved nearly constant travel,

and as a child I rarely saw him. In our forged letter to Dr.

Kaiser, Martha and I, or I should say “Father,” wrote that the

family had recently been contacted directly by the government

regarding my participation in the BFI program and that Agent Benton

had personally guaranteed him my safety for the duration of my stay

in Indian territory. Because Martha had been privy to the entire

interview process, I knew that I had passed all the necessary

requirements and had been judged to be a prime candidate for the

program (not that this represents any great accomplishment on my

part considering that the main criterion for acceptance was that

one be of child-bearing age and condition, and not so insane as to

be incapacitated. It is, I believe, safe to say that the government

was less interested in the success of these matrimonial unions than

they were in meeting their quota— something that Father, ever the

businessman and pragmatist could appreciate).

Thus in our letter, Father gave his

full blessing for me to participate in, as I believe we wrote “this

exciting and high-minded plan to assimilate the heathens.” I know

that Father has always viewed the western savages primarily as an

impediment to the growth of American agriculture—he detests the

notion of all that fertile plain going to waste when it could be

put to good Biblical use filling his grain elevators. The truth is,

Father harbors a deep-seated hatred of the Red Man simply for being

a poor businessman—a shortcoming which Father believes to be the

most serious character flaw of all. At his and Mother’s endless

dinner parties he is fond of giving credit to his and his wealthy

guests’ great good fortunes by toasting the Sac Chief Black Hawk,

who once said that “land cannot be sold. Nothing can be sold but

for those things that can be carried away”—a notion that Father

found enormously quaint and amusing.

Too—and I must acknowledge this fact—I

believe that secretly Father might actually have appreciated this

opportunity to be rid of me, of the shame that my behavior, my

“condition” has brought on our family. For if the truth be known,

Father is a terrible snob. In his circle of friends and business

cronies the stigma of having a lunatic—or, even worse, a sexually

promiscuous daughter—must have been nearly unbearable for

him.

So he went on in his letter, in his

typically overblown but distracted manner—in the same tone he might

employ if he were giving permission for me to be sent off to

finishing school for young ladies (perhaps it is simply due to the

fact that the same blood flows through our veins, but it was almost

diabolically simple for me to imitate Father’s writing style)—to

state his conviction that the “bracing Western air, the hearty

native life in the glorious out-of-doors, and the fascinating

cultural exchange might be just what my poor wayward daughter

requires to set her addled mind right again.” It is an astonishing

thing, is it not, the notion of a father being asked (and giving!)

permission for his daughter to copulate with savages?

Enclosed with Father’s letter were the

signed hospital release papers, all of which Martha had delivered

by private messenger to Dr. Kaiser’s office—a tidy and ultimately

perfectly convincing little package.

Of course, when her part in the

deception was discovered, as it surely would be, Martha knew that

she faced immediate dismissal—possibly even criminal prosecution.

And thus it is, that my true, intrepid friend—childless and

loveless (and if the truth be told rather plain to look upon),

facing in all probability a life of spinsterhood and

loneliness—enlisted in the BFI program herself. She rides beside me

on this very train … and so at least I do not embark alone on this

greatest adventure of my life.

It would be disingenuous of me to say

that I have no trepidations about the new life that awaits us. Mr.

Benton assured us that we are contractually obligated to bear but

one child with our Indian husbands, after which time we are free to

go, or stay, as we choose. Should we fail to become with child, we

are required to remain with our husbands for two full years, after

which time we are free to do as we wish … or, at least, so say the

authorities. It has not failed to occur to me that perhaps our new

husbands might have different thoughts about this arrangement.

Still, it seems to me a rather small price to pay to escape that

living Hell of an asylum to which I would quite likely have been

committed for the rest of my life. But now that we have actually

embarked upon this journey, our future so uncertain, and so

unknown, it is impossible not to have misgivings. How ironic that

in order to escape the lunatic asylum I have had to embark upon the

most insane undertaking of my life.

But honestly, I believe that poor

naive Martha is eager for the experience; excited about her

matrimonial prospects, she seems to be fairly blooming in

anticipation! Why just a few moments ago she asked me, in rather a

breathless voice, if I might give her some advice about carnal

matters! (It appears that, due to the reason given for my

incarceration, everyone connected with the institution—even my one

true friend—seems to consider me somewhat of an authority in such

matters.)

“What sort of advice, dear friend?” I

asked.

Now Martha became terribly shy,

lowered her voice even further, leaned forward, and whispered.

“Well … advice about … about how best to make a man happy … I mean

to say, about how to satisfy the cravings of a man’s

flesh.”

I laughed at her charming innocence.

Martha hopes to carnally satisfy her savage! “Let us assume, first

of all,” I answered, “that the aboriginals are similar in their

physical needs to men of our own noble race. And we have no reason

to believe otherwise, do we? If indeed all men are similarly

disposed in matters of the heart and of the flesh, it is my limited

experience that the best way to make them happy—if that is your

true goal—is to wait on them hand and foot, cook for them, have

sexual congress whenever and wherever they desire—but never

initiate the act yourself and do not demonstrate any forwardness or

longings of your own; this appears to frighten men—most of whom are

merely little boys pretending to be men. And, perhaps most

importantly, just as most men fear women who express their physical

longings, so they dislike women who express opinions—of any sort

and on any subject. All these things I learned from Mr. Harry Ames.

Thus I would recommend that you agree unequivocably with everything

your new husband says … oh, yes, one final thing—let him believe

that he is extremely well endowed, even if, especially if, he is

not.”

“But how will I know whether or not he

is well endowed?” asked my poor innocent Martha.

“My dear,” I answered. “You do know

the difference between, let us say a breakfast sausage and a

bratwurst? A cornichon and

a cucumber? A pencil and a pine tree?”

Martha blushed a deep shade of

crimson, covered her mouth, and began to giggle uncontrollably. And

I, too, laughed with her. It occurs to me how long it has been

since I really laughed … it does feel wonderful to laugh

again.

My Dearest Sister

Hortense,

You have by this time perhaps heard

news of my sudden departure from Chicago. My sole regret is that I

was unable to be present when the family was notified of the

circumstances of my “escape” from the “prison” from which you had

all conspired to commit me. I would especially have enjoyed seeing

Father’s reaction when he learned that I am soon to become a

bride—yes, that’s right, I am to wed, and perforce, couple with a

genuine Savage of the Cheyenne Nation!—Hah! Speaking of moral

perversion. I can just hear Father blustering: “My God, she really

is insane!” What I would give to see his face!

Now, truly, haven’t you always known

that your poor wayward little sister would one day embark on such

an adventure, perform such a momentous deed? Imagine me, if you are

able, riding this rumbling train west into the great unknown void

of the frontier. Can you picture two more different lives than

ours? You within the snug (though how dreary it must be!) confines

of the Chicago bourgeoisie, married to your pale banker Walter

Woods, with your brood of pale offspring—how many are there now, I

lose track, four, five, six of the little monsters?—each as

colorless and shapeless as unkneaded bread dough.

But forgive me, my sister, if I appear

to be attacking you. It is only that I may now, at last—freely and

without censor or fear of recriminations— voice my anger to those

among my own family who so ill-treated me; I can speak my mind

without the constant worry of further confirming my insanity,

without the ever-present danger that my children will be torn from

me forever—for all this has come to pass, and I have nothing left

to lose. At last I am free—in body, mind, and spirit … or as free

as one can be who has purchased her freedom with her womb

…

But enough of that … now I must tell

you something of my adventure, of our long journey, of the

extraordinary country I am seeing. I must tell you of all that is

fascinating and lonely and desolate … you who have barely set foot

outside Chicago, can simply not imagine it all. The city is

bursting at its very seams, abustle with rebuilding out of the

ashes of the devastating great fire, expanding like a living

organism out into the prairie (well, is it any wonder then that the

savages rebel as they are pushed ever further west?). You cannot

imagine the crowds, the human congress, the sheer activity on what

used to be wild prairie when we were children. Our train passed

through the new stockyard district—very near the neighborhood where

Harry and I lived. (You never did come to visit us, did you,

Hortense? … Why does that not surprise me?) There the smokestacks

spew clouds of all colors of the rainbow—blue and orange and

red—which when they enter the air seem to intermingle like oil

paints mixed on a palette. It is quite beautiful in a grotesque

sort of way, like the paintings of a mad god. Past the

slaughterhouses, where the terrified cries of dumb beasts can be

heard even over the steady din of the train, their sickening stench

filling the car like rancid syrup. Finally the train burst from the

shroud of smoke that blankets the city, as though it had come out

of a dense fog into the clear-plowed farm country, the freshly

turned soil black and rich, Father’s beloved grain crops just

beginning to break ground.

I must tell you that in spite of

Father’s insistence to the contrary, the true beauty of the prairie

lies not in the perfect symmetry of farmlands, but where the

farmlands end and the real prairie begins—a sea of natural grass

like a living, breathing thing undulating all the way to the

horizon. Today I saw prairie chickens, flocks of what must have

been hundreds, thousands, flushing away in clouds from the tracks

as we passed. I could only imagine the sound of their wings over

the roar of the train. How extraordinary to see them on the wing

like this after the year I spent laboring in that wretched factory

where we processed the birds and where I thought I could never bear

to look at another chicken as long as I lived. I know that you and

the rest of the family could not understand my decision to take

such menial work or to live out of wedlock with a man so far

beneath my station in life, and that this has always been spoken of

among you as the first outward manifestation of my insanity. But,

don’t you see, Hortense, it was precisely our cloistered upbringing

under Mother and Father’s roof that spurred me to seek contact with

a larger world. I’d have suffocated, died of sheer boredom, if I

stayed any longer in that dark and dreary house, and although the

work I took in the factory was indeed loathsome, I will never

regret having done it. I learned so much from the men and women

with whom I toiled; I learned how the rest of the world—families

less fortunate than ours, which, of course constitutes the vast

majority of people—lives. This is something you can never know,

dear sister, and which you will always be poorer in soul for having

missed.

Not that I recommend to you a job in

the chicken factory! Good God, I shall never get over the stink of

it, my hands even now when I hold them up to my face seem to reek

of chicken blood, feathers, and innards … I think that I shall

never eat poultry again as long as I live! But I must say my

interest in the birds is somewhat renewed in seeing the wild

creatures flying up before the train like sparks from the wheels.

They are so beautiful, fanning off against the setting sun, their

tangents helping to break the long straight tedium of this journey.

I have tried to interest my friend Martha, who sits beside me, in

this spectacle of wings, but she is very soundly asleep, her head

jostling gently against the train window.

But here has occurred an amusing

encounter: As I was watching the birds flush from the tracks, a

tall, angular, very pale woman with short-cropped sandy hair under

an English tweed cap came hurrying down the aisle of our car,

stooping to look out each window at the birds and then moving on to

the next seat. She wears a man’s knickerbocker suit of Irish

thornproof, in which, with her short hair and cap it might be easy

to mistake her for a member of the opposite sex. Her mannish outfit

includes a waistcoat, stockings, and heavy walking brogues, and she

carries an artist’s sketch pad.

“Excuse me, please, won’t you?” the

woman asked of each occupant of each seat in front of which she

leaned in order to improve her view out the window. She spoke with

a distinct British accent. “Do please excuse me. Oh, my goodness!”

she exclaimed, her eyebrows raised in an expression of delighted

surprise. “Extraordinary! Magnificent! Glorious!”

By the time the Englishwoman reached

the unoccupied seat beside me the prairie chickens had set their

wings and sailed off over the horizon and she flopped down in the

seat all gangly arms and legs. “Greater prairie chicken,” she said.

“That is to say, Tympanuchus

cupido, actually a member of the grouse family,

commonly referred to as the prairie chicken. The first I’ve ever

seen in the wilds, although, of course, I’ve seen specimens. And of

course I have studied extensively the species’ eastern cousin, the

heath hen, during my travels about New England. Named after the

Greek tympananon,

‘kettledrum,’ and ‘echein,’ to have a drum, aluding both to

the enlarged esophagus on the sides of the throat, which in the

male becomes inflated during courtship, as well as to the booming

sound which the males utter in their aroused state. And further

named after the ‘blind bow boy,’ son of Venus—not, however with any

illusion to erotic concerns, I should hasten to add, but because

the long, erectile, stiff feathers are raised like small rounded

wings over the head of the male in his courtship display, and have

therefore been likened to Cupid’s wings.”

Now the woman suddenly turned as if

noticing me for the first time, and with the same look of perpetual

surprise still etched in her milk-pale English countenance—eyebrows

raised and a delighted smile at her lips as if the world itself

were not only wonderful, but absolutely startling. I liked her

immediately. “Do please excuse me for prattling on, won’t you?

Helen Elizabeth Flight, here,” she said, thrusting her hand forward

with manly forthrightness. “Perhaps you’re familiar with my work?

My book Birds of Britain

is currently in its third printing—letterpress provided by my dear

companion and collaborator, Mrs. Ann Hall of Sunderland.

Unfortunately, Mrs. Hall was too ill to accompany me when I

embarked on my tour of America to gather specimens and make

sketches for our next opus, Birds of

America—not to be confused, of course, with Monsieur

Audubon’s series of the same name. An interesting artist, Mr.

Audubon, if rather too fanciful for my tastes. I’ve always found

his birds to be rendered with such … caprice! Clearly he threw

biological accuracy to the wind. Wouldn’t you agree?”

I could see that this question was

intended to be somewhat more than rhetorical, but just as I was

attempting to form an answer, Miss Flight asked: “And you are?”

still looking at me with her eyebrows raised in astonished

anticipation, as if my identity were not only a matter of the

utmost urgency but also promised a great surprise.

“May Dodd,” I answered.

“Ah, May Dodd! Quite,” she said. “And

a smart little picture of a girl you are, too. I suspected from

your fair complexion that you might be of English

descent.”

“Scottish actually,” I said, “but I’m

thoroughly American, myself. I was born and raised in Chicago,” I

added somewhat wistfully.

“And don’t tell me that a lovely

creature like you has signed up to live with the savages?” asked

Miss Flight.

“Why yes I have,” I said. “And

you?”

“I’m afraid that I’ve run a trifle

short of research funds,” explained Miss Flight with a small

grimace of distaste for the subject. “My patrons were unwilling to

advance me any more money for my American sojourn, and this seemed

like quite the perfect opportunity for me to study the birdlife of

the western prairies at no additional expense. A frightfully

exciting adventure, don’t you agree?”

“Yes,” I said, with a laugh,

“frightfully!”

“Although I must tell you a little

secret,” she said, looking around us to see that we were not

overheard. “I am unable to have children myself. I’m quite sterile!

The result of a childhood infection.” Her eyebrows shot up with

delight. “I lied to the examiner in order to be accepted into the

program !

“Now you will excuse me, Miss Dodd,

won’t you?” said Miss Flight, suddenly all business again. “That is

to say, I must quickly make some sketches and record my impressions

of the magnificent greater prairie chicken while the experience is

still fresh in mind. I hope, when the train next stops, to be able

to descend and shoot a few as specimens. I’ve brought with me my

scattergun, especially manufactured for this journey by

Featherstone, Elder & Story of Newcastle upon Tyne. Perhaps you

are interested in firearms? If so, I’d love to show it to you. My

patrons, before they ran into financial difficulties and left me

stranded on this vast continent, had the gun especially built for

me, specifically for my travels in America. I’m rather proud of it.

But do excuse me, won’t you? I’m so terribly pleased to have met

you. Wonderful that you’re along! We must speak at greater length.

I have a feeling that you and I are going to be spiffing good

friends. You have the most extraordinarily blue eyes, you know, the

color of an Eastern bluebird. I shall use them as a model to mix my

palette when I paint that species if you don’t terribly mind. And

I’m fascinated to learn more of your opinion on Monsieur Audubon’s

work.” And with that the daffy Englishwoman took her

leave!

While we are on the subject, and since

Martha is proving at present to be exceedingly dull company, let me

describe to you, dear sister, some of my other fellow travelers,

who provide the only other diversion on this long, straight,

monotonous iron road through country that while beautiful in its

vast and empty reaches, can hardly be described as scenic. I’ve

barely had time yet to acquaint myself with all of the women, but

our common purpose and destination seems to have fostered a certain

easy familiarity among us—personal histories and intimacies are

exchanged without the usual period of tedious social posturing or

shyness. These women—hardly more than girls really—are all either

from the Chicago area or other parts of the Middle West, and come

from all circumstances. Some appear to be escaping poverty or

failed romances, or, as in my case, unpleasant “living

arrangements.” Hah! While there is only one other girl from my

asylum, there are several in our group from other such public

facilities around the city. Some are considerably more eccentric

even than I. But then it was my observation in the asylum that

nearly every resident there took solace in the fact that they could

point to someone else who was madder than they. One, named Ada

Ware, dresses only in black, wears a widow’s veil, and has

perpetual dark circles of grief beneath her eyes. I have yet to see

her smile or make any expression whatsoever. “Black Ada” the others

call her.

You will, perhaps, remember Martha,

whom you met on the sole occasion when you visited me in the

asylum. She is a sweet thing, barely two years younger than I,

though she seems younger, and homely as a stick. I am forever

indebted to her, for it was Martha who was so invaluable in helping

me to obtain my liberty.

As mentioned, one other girl from my

own institution survived the selection process—while a number of

others declined to accept Mr. Benton’s offer. It seemed remarkable

to me at the time that they would give up the opportunity for

freedom from that ghastly place, simply because they were squeamish

about conjugal relations with savages. Perhaps I will live to

regret saying this, but how could it be any worse than

incarceration in that dank hellhole for the rest of one’s

life?

This young girl’s name is Sara

Johnstone. She’s a pretty, timid little creature, barely beyond the

age of puberty. The poor thing evidently lacks the power of

speech—by this I do not mean that she is simply the quiet sort—I

mean that she seems unable, or at least unwilling, to utter a word.

She and I had, perforce, very little contact at the hospital, and

therefore hardly any opportunity to get to know one another. I have

a suspicion that this will all change now, for she seems to have

attached herself to me and Martha. She sits facing us on the train,

and frequently leans forward with tears in her eyes to grasp my

hand and squeeze it fiercely. I know nothing of her past or the

reason why she was originally confined in the institution. She has

no family and according to Martha had evidently been there long

before I arrived—ever since she was a young child. Nor do I know

who supported her there—as we both know that wretched place was not

for charity cases. Martha has intimated that Dr. Kaiser himself,

the director of the hospital, volunteered the poor girl for the

program as a way of being rid of her—what Father might recognize as

a cost-cutting measure—for according to Martha, the girl was

treated very much like a “poor relation” in the hospital.

Furthermore, though we are hardly free to discuss the matter with

the poor thing sitting directly in front of us, Martha has

suggested that the child may, in fact, have had some familial

connection with the Good Doctor—possibly, we have speculated, she

is the product of his own romantic liaison with a former patient?

Although one must wonder what kind of man would send his own

daughter away to live among savages … Whatever the child’s

situation, I find it troubling that she was accepted into this

program. She is such a frail little thing, terrified of the world,

and so obviously ill prepared for what must certainly prove to be

an arduous duty. Indeed, how could she be prepared for any

experience in the real world, having grown up behind brick walls

and iron-barred windows? I am certain that, like Martha, the girl

is without experience in carnal matters, unless the repulsive night

monster Franz visited her, too, in the dark … which I pray for her

sake that he did not. In any case, I intend to watch over the

child, to protect her from harm if it is within my power to do so.

Oddly, her very youth and fearfulness seem to give me strength and

courage.

Ah, and here come the Kelly sisters of Chicago’s Irish town, Margaret and Susan, swaggering down the aisle—redheaded, freckle-faced identical twin lassies, thick as thieves, which in their case is somewhat more than an idle expression. They take everything in these two; their shrewd pale green eyes miss nothing; I clutch my purse to breast for safekeeping.

One of them, I cannot yet tell them

apart, slips into the seat beside me. “’Ave ya got some tobacco on ye, May?” she

asks in a conspiratorial tone, as if we are the very best of

friends though I hardly know the girl. “I’d be loookin’ to roll me a smoke.”

“I’m afraid I don’t smoke,” I

answer.

“Aye,’twas easier to get a smoke in prison,

than it is on this damn train,” she says. “Isn’t that so,

Meggie?”

“It’s sartain, Susie,” Meggie

answers.

“Do you mind my asking why you girls

were in prison?” I ask. I tilt my notebook toward them. “I’m

writing a letter to my sister.”

“Why, we don’t mind at-tall, dear,” says Meggie, who leans on

the seat in front of me. “Prostitution and Grand Theft—ten-year

sentences in the Illinois State Penitentiary.” She says this with

real bravado in her voice as if it is a thing of which to be very

proud, and as I write she leans down closer to make sure that I

record the details correctly. “Aye, don’t forget the Grand Theft,” she

repeats, pointing her finger at my notebook.

“Right, Meggie,” adds Susan, nodding

her head with satisfaction. “And we’d not have been apprehended,

either, if it weren’t for the fact that the gentleman we turned

over in Lincoln Park’ appened to be a municipal jeewdge. Aye, the old reprobate tried to

solicit us for sexual favors. ‘Twins!’ he said. ‘Two halves of a

bun around my sausage’ he desired to make of us. Ah ya beggar!—we

gave him two halves of a brick on either side of his damn head, we

did! In two shakes of a lamb’s tail we had his pocket watch and his

wallet in our possession—thinking in our ignorance what great good

fortune that he was carrying sech a large soom of cash. No doubt His

Jeewdgeship’s weekly bribe

revenue.”

“It’s sartain, Susie, and that would’ve been the

end of it,” chimes in Margaret, “if it weren’t for that damn cash.

The jeewdge went directly

to his great good pal the Commissioner of Police and a

manhoont the likes of

which Chicago has never before seen was launched to bring the

infamous Kelly twins to juicetice!”

“’Tis the God’s own truth, Meggie,” says

Susan, shaking her head. “You probably read about us in the

newspaper, Missy,” she says to me. “We were quite famous for a

time, me and Meggie. After a short trial, which the public advocate

charged with our defense spent nappin’—the old bugger—we were

sentenced to ten years in the penitentiary. Aye, ten years just for defendin’ our honor

against a lecherous old jeewdge, with a pocket full of bribe money,

if you can believe that, Missy.”

“And your parents?” I ask. “Where are

they?”

“Oh, we ‘ave no idea, darlin’,” says Margaret. “We

were foundlings, you see. Wee babies left on the steps of the

church. Isn’t that so, Susie? Grew up in the city’s Irish

orphanage, but we didn’t really care for the place.

Aye, we been living by our

wits ever since we roon

away from there when we were just ten years old.”

Now Margaret stands straight again and

scans the other passengers with a certain predatory interest. Her

gaze comes to rest on the woman sitting across the aisle from us—a

woman named Daisy Lovelace; I have only spoken to her briefly, but

I know that she is a Southerner and has the distinct look of ruined

gentry about her. She holds an ancient dirty white French poodle on

her lap. The dog’s hair is stained red around its butt and muzzle,

and around its rheumy, leaking eyes.

“Wouldn’t ’appen to ’ave a bit of tobacco, on ye, Missy, would

ya now?” Margaret asks

her.

“Ah’m afraid naught”, says the woman in a slow drawl, and

in not a particularly friendly tone.

“Loovely little dog, you’ve got there,” says

Margaret, sliding into the seat beside the Southerner. “What’s its

name, if you don’t mind me

askin’?” The twin’s insinuating manner is transparent; it is clear

that she is not interested in the woman’s dog.

Ignoring her, the Lovelace woman sets

her dog down on the floor between their feet. “You go on now an’

make teetee, Feeern

Loueeese,” she coos to it in an accent as thick as

cane molasses, “Go wan now

sweethaart. You make

teetee for Momma.” And the

wretched little creature totters stiffly up the aisle sniffling and

snorting, finally squatting to pee by a vacant seat.

“Fern Louise, is it then?” says

Meggie. “Isn’t that a grand name, Susie?”

“Loovely, Meggie,” Susan says. “A

loovely little

dog.”

Still ignoring them, the Southern

woman pulls a small silver flask from her purse and takes a quick

sip, which act is of great interest to the twins.

“Is that whiskey you’ve got there,

Missy?” Margaret asks.

“No, it is naught whiskey,” says the woman coolly. “It

is mah nuurve medicine,

doctor’s order, and no,

you may not have a taste of it.”

The twins have met their match with

this one I can see!

Now here comes my friend, Gretchen Fathauer, bulling her way down the aisle of the train, swinging her arms and singing some Swiss folksong in a robust voice. Gretchen never fails to cheer us all up. She is a big-hearted, enthusiastic soul—a large, boisterous, buxom rosy-cheeked lass who looks like she might be able to spawn single-handedly all the babes that the Cheyenne nation might require.

By now we all know Gretchen’s history

almost as well as our own: Her family were immigrants from

Switzerland, who settled on the upland prairie west of Chicago to

farm wheat when Gretchen was a girl. But the family farm failed

after a series of bad harvests caused by harsh winters, blight, and

insect attack, and Gretchen was forced to leave home as a young

woman and seek employment in the city. She found work as a domestic

with the McCormick family—yes, the very same—Father’s dear friend

Cyrus McCormick, who invented the reaper … isn’t it odd, Hortense,

to think that we probably visited the McCormicks in our youth at

the same time that Gretchen was employed there—but of course we

would never have paid any attention to the bovine Swiss

chambermaid.

Gretchen longed to have a family of

her own and one day she answered an advertisement in the

Tribune seeking

“mail-order” brides for western settlers. She posted her

application and several months later was notified that she had been

paired with a homesteader from Oklahoma territory. Her intended was

to meet her at the train station in St. Louis on an appointed day,

and convey her to her new home. Gretchen gave notice to the

McCormicks and two weeks later boarded the train to St. Louis. But

alas, although she has a heart of gold, Gretchen is terribly plain

… indeed, I must confess that she is rather more than plain, to the

extent that one of the less kind members of our expedition has

referred to the poor dear as “Miss Potato Face” … and even those

more charitable among us must admit that her countenance does have

a certain unfortunate tuberous quality.

Well, Gretchen’s intended had only to

take one look at her, with which he excused himself under pretense

of fetching his baggage, and Gretchen never laid eyes on the

miserable cur again. She tells the story now with great good humor,

but she was clearly devastated. She had given up everything—and was

now abandoned at the train station in a strange city, with only her

suitcase, a few personal effects, and the meager savings from her

former employment. She could not bear the humiliation of going back

to Chicago and asking the McCormicks for her old job. Nor was the

possibility of returning to her family, shamed thusly by

matrimonial rejection, any more appealing to her. No, Gretchen was

determined to have a husband and children one way or another. She

sat on the bench at the train station and wept openly at her

plight. It was at that very moment that a gentleman approached her.

He handed her a small paper flyer on which was printed the

following:

If you are a healthy young woman of childbearing age, who seeks matrimony, exotic travel, and adventure, please present yourself to the following address promptly at 9.00 a.m., Thursday morning on the twelfth day of February, the year of our Lord, 1875.

Gretchen laughs when she tells the

story—a great hearty bellow—and says in her heavy accent,

“Vell, you know, I

tought this young fellow

must be a messenger from God, I truly do. And ven I go to to dis place, and dey ask me if I like to marry a Cheyenne

Indian fellow and have his babies, I say: ‘Vell, I tink

de savages not be so chooosy, as dat farmer yah? Sure, vy not? I make beeg, strong babies for my new

hustband. Yah, I feed

da whole damn nursery,

yah?’” And Gretchen pounds

her massive breast and laughs and laughs.

Which causes all the rest of us to

laugh with her.

Unable to break the Southern woman’s steely indifference to them, the Kelly sisters have moved on to try their luck in the next car. They remind me of a pair of red foxes prowling a meadow for whatever they might turn up.

Just now as I was writing, my new

friend, Phemie, came to sit beside me. Euphemia Washington is her

full name—a statuesque colored girl who came to Chicago via Canada.

She is about my same age, and quite striking, I should say nearly

fierce, in appearance, being over six feet in height, with

beautiful skin, the color of burnished mahogany—a finely formed

nose with fiercely flared nostrils, and full Negro lips. I’m sure,

dear sister, that you and the family will find it perfectly

scandalous to learn that I am now fraternizing with Negroes. But on

this train all are equal, at least such is the case in my

egalitarian mind.

“I am writing a letter to my sister at

home,” I said to her, “describing the circumstances of some of the

girls on the train. Tell me how you came to be here, Phemie, so

that I may make a full report to her.”

At this she chuckled, a rich warm

laugh that seemed to issue from deep in her chest. “You are the

first person who has asked me that, May,” she said. “And why would

your sister be interested in the nigger girl? Some of the others

seem quite distressed that I am along.” Phemie is very well spoken,

with the most lovely, melodic voice that I’ve ever heard—deep and

resonant, her speech like a poem, a song.

It occurred to me that, truth be told,

you, dear sister, probably would not be interested in hearing about

the nigger girl. Of course, this I did not say to

Phemie.

“How did you happen to go to Canada,

Phemie?” I asked.

She chuckled again. “You don’t think

that I look like a native Canadian, May?”

“You look like an African, Phemie,” I

said bluntly. “An African princess!”

“Yes, my mother came from a tribe

called the Ashanti,” Phemie said. “The greatest warriors in all of

Africa,” she added. “One day when she was a young girl she was

gathering firewood with her mother and the other women. She fell

behind, and sat down to rest. She was not worried, for she knew

that her mother would return for her. As she sat, leaning against a

tree, she fell asleep. And when she woke up, men from another

tribe, who spoke a tongue she did not understand, stood round her.

She was only a child, and she was very frightened.

“They took her away to a strange

place, and kept her there in chains. Finally she was put in the

hold of a ship with hundreds of others. She was many weeks at sea.

She did not know what was happening to her, and she still believed

that her mother would come back for her. She never stopped

believing that. It kept her alive.

“The ship finally reached a city the

likes of which my mother had never before seen or imagined. Many

had died on route but she had lived. In the city she was sold at

auction to a white man, a cotton shipper, who owned a fleet of

sailing vessels in the port city of Apalachicola,

Florida.

“My mother’s first master was very

good to her,” Phemie continued. “He took her into his home where

she did domestic duties and even received a bit of education. She

learned to read and write, a thing unheard of among the other

slaves. And when she became a young woman, her master took her into

his bed.

“I was the child born of this union,”

Phemie said. “I, too, grew up in that house, where I was given

lessons in the kitchen by the tutor of Master’s ‘real’ children—his

white family. Eventually the mistress discovered the truth of my

parentage—perhaps she finally saw some resemblance between the

kitchen nigger’s child and her own children. And one night when I

was not yet seven years old, two men, slave merchants, came and

took me away—just as my mother had been taken from her family. She

wept and pleaded and fought the men, but they struck her and

knocked her to the ground. That was the last time I ever saw my

mother, lying unconscious with her face battered and bleeding …”

Phemie paused here and looked out the train window, tears

glistening in the corners of her eyes.

“I was sold to the owner of a

plantation outside Savannah, Georgia,” she continued. “He was a bad

man, an evil man. He drank and treated his slaves with terrible

cruelty. The first day that I arrived there he had me branded on

the back with his own initials … Yes, he burned his initials into

the flesh of all his slaves so that they would be easily identified

if ever they ran away. I was still just a child, eight years old,

but after the first week that I was there, the man began to have me

sent to his private quarters at night. I do not need to tell you

what happened there … I was badly hurt …

“Several years passed this way,” she

went on in a softer voice. “Then one day a Canadian natural

scientist came to visit the plantation. He came under the guise of

studying the flora and fauna there—but he was an abolitionist and

his true purpose was to spread the word to the slaves about the

underground railroad. He carried excellent letters of introduction

and was unwittingly welcomed at all the plantations. Because I had

a little education, and because I had always been fascinated with

wild things of all kinds, my master charged me with accompanying

the naturalist on his daily excursions to collect specimens. Over

the several days of his visit, the man spoke to me often of Canada,

told me that every man, woman, and child lived free and equal

there—that none was owned by another. The scientist liked me and

took pity on me. He told me that I was too young to attempt to

escape alone but that I should encourage some of the older slaves

to take me with them. He showed me maps of the best routes north

and gave me the names of people along the way who would help

us.

“I spoke to some of the others, but

all were too terrified of the Master to attempt such an escape.

They had seen what Master did to runaway slaves who were returned

to him.

“One night a week or so after the man

left, after I had returned weeping and in great pain to the slaves

quarters from Master’s bedroom, I made a bundle of a few clothes

and what little food I could gather and I left alone. I did not

care if I died trying to escape. Death seemed welcome compared to

my life.

“I was young and strong,” Phemie said,

“and over the next several nights I ran through the forest and

swamps and canebrakes. I never stopped running. Sometimes I could

hear the hounds baying behind me, but the naturalist had instructed

me to wade up streambeds and across ponds, which would cause the

dogs to lose the scent. I ran and I ran.

For weeks I traveled north, moving by

night, hiding in the undergrowth during the day. I ate what I could

scavenge in the forest and fields, wild roots and greens, sometimes

a bit of fruit or vegetables stolen from farms or gardens. I was

hungry and often I did not know where I was, but I kept the North

Star always before me and I looked for landmarks which the

scientist had described to me. Often I longed to go into the towns

I passed to beg a little food, but I dared not. Upon my back I

still wore Master’s brand, and if captured I would surely be

returned to him and terribly punished.

“In those weeks alone in the

wilderness, I began to remember the stories my mother had told me

of her own people, of the men hunting and the women gathering from

the earth. I would never have survived my journey to the land of

freedom were it not for what my mother had taught me about the

wilds. My grandmother’s knowledge, passed down through my mother,

saved my life. It was as if, all these years later, my mother’s

mother came back for me just as she had always believed she would

come for her …

“It was several months before I

finally crossed into Canada,” Phemie continued. “There I called on

people whose names the naturalist had given me and eventually I was

placed in the home of a doctor’s family. I was well treated there

and was able to continue my education. I lived with the doctor and

his family for almost ten years—I worked for them and was paid an

honest wage for my labors.

“One day I happened to see a small

notice in the newspaper requesting young single women of any race,

creed, or color to participate in an important volunteer program on

the American frontier. I answered the advertisement … and, here we

are … you and I.”

“But if you were happy with the

doctor’s family in Canada,” I asked Phemie, “why did you wish to

leave there, to come on this mad adventure?”

“They were fine people,” Phemie said.

“I loved them and will be forever grateful to them. But you see,

May, I was still a servant. I was paid for my work, that is true,

but I was still a servant to white folks. I dreamed of more for

myself, I dreamed to be a free woman, truly free, on my own and

beholden to no others. I owed that to my mother, and to my people.

I know that as a white woman, it must be difficult for you to

understand this.”

I patted Phemie on the back of her

hand. “You’d be surprised, Phemie,” I said, “at how well I

understand the longing for freedom.”

But now an ugly thing has occurred,

spoiling the moment. As Phemie and I were sitting together, the

Southern woman Daisy Lovelace, seated across the aisle, set her

ancient miserable little poodle down on the seat beside her and

said in a voice so loud that we couldn’t help but turn to look.

“Feeern Loueeese,” she

said, “would you rather be a niggah, or would you rather be

daid?” upon which cue the

little dog teetered stiffly and then rolled over on its back with

its little bowed legs sticking straight in the air. Miss Lovelace

shrieked with mean-spirited laughter.

“Wretched woman!” I muttered. “Pay no

attention to her, Phemie.”

“Of course I don’t,” Phemie said,

unconcerned. “The poor soul is drunk, May, and believe me, I’ve

heard far worse than that. I’m sure that such a parlor trick was a

source of great amusement to her plantation friends. And now she

finds herself among our motley group, where she must at least

assert her superiority over the nigger girl. I think we should not

judge her just yet.”

I have dozed off, with my head on Phemie’s shoulder, only to be rudely awakened by the shrill voice of a dreadful woman named Narcissa White, an evangelical Episcopalian who is enrolled in the program under the auspices of the American Church Missionary Society. Now Miss White comes bustling down the aisle of the train passing out religious pamphlets. “‘Ye who enter the wilderness without faith shall perish’ said the Lord Jesus Christ,” she preaches, and other such nonsense, which only serves to further agitate the others—some of whom already seem as skittish as cattle going to the slaughterhouse.

I’m afraid that Miss White and I have

taken an instant dislike to one another, and I fear that we are

destined to become bitter enemies. She is enormously tiresome and

bores us all witless with her sanctimonious attitudes and

evangelical rantings. As you well know, Hortense, I have never had

much interest in the church. Perhaps the hypocrisy inherent in

Father’s position as a church elder, while remaining one of the

least Christ-like men I’ve ever known, has something to do with my

general cynicism toward organized religion of all

kinds.

The White woman has already stated

that she has no intention of bearing a child with her Cheyenne

husband, nor indeed of having conjugal relations with him, and she

assures us that she signed up for this mission strictly as a means

of giving herself to the Lord Jesus—to save the soul of her heathen

intended by teaching him “the ways of Christ and the true path to

salvation,” as she puts it in her most pious manner. Evidently she

intends to distribute her pamphlets among the savages, and seemed

not in the least deterred when I pointed out to her that very

likely they won’t be able to read them. It may be blasphemous for

me to say so, but personally, I believe that our Christian God as

He is represented by the likes of Miss White may be of somewhat

limited use to the savages …

I will write to you again soon, my

dearest sister …

We crossed the Missouri River three

days ago, spending one night in a boardinghouse in Omaha. Our

military escort, or “guard” as I prefer to call them, treat us more

as prisoners than as volunteers in the service of our

government—they are contemptuous and snide, and have a gratingly

familiar air that suggests some knowledge of the Faustian bargain

we have struck with our government. None of us was permitted to go

abroad in Omaha, nor even allowed to leave the

boardinghouse—perhaps they fear that we might have a change of

heart and seek to escape.

The next morning we boarded another

train, which for the past two days has followed along a bluff

overlooking the Platte River—not much of a river really—wide,

slow-moving, and turgid.

We passed through the little

settlement of Grand Island, where we took on supplies but were not

permitted to disembark, westward through the muddy village of North

Platte, where we were once again forbidden to so much as stretch

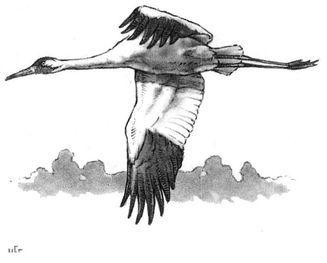

our legs at the station. We did witness a remarkable spectacle

yesterday morning at dawn—thousands, no I would more accurately

guess, millions of cranes on the river. As if by some signal,

perhaps simply frightened by the passing of our train, they all

suddenly took flight, rising off the water as one being, like an

enormous sheet lifted by the wind. Our British ornithologist, Miss

Flight, was absolutely beside herself, rendered all but speechless

by the spectacle. “Glorious!” she said, patting her flat chest.

“Absolutely glorious!” Truly I thought the woman’s eyebrows were

going to shoot right off the top of her head. “A masterpiece,” she

marveled. “God’s masterpiece!” I found this at first to be an odd

remark, but soon realized how accurate a description it really was.

The birds made a noise we could hear even over the roar of our

locomotive. A million wings—imagine it!—like the sound of rumbling

thunder or a waterfall, punctuated by the strange, otherworldly

cries of the cranes, their wingbeats at once ponderous and elegant,

their bodies so large that flight seemed improbable, legs dangling

awkwardly beneath them like the rag tails of a child’s kite. God’s

masterpiece … and perhaps after my long, spartan confinement behind

four walls and a locked door such a spectacle of freedom and

fecundity seems even more wonderful. Ah, but on this morning the

earth seems like an especially fine place to be alive and free! I

think that I shall not mind living in the wilderness …

I have no true sense of this strange new country yet. Compared to Illinois, the vast prairies hereabouts seem more arid, less productive, and the few farms that we pass down in the river floodplain appear poor—boggy and undeveloped. The people working in the fields look gaunt-eyed and discouraged as if they have given up already any dreams of success or prosperity. We passed one poor fellow trying futilely to plow a flooded field with a team of oxen; it was clearly a hopeless endeavor, for his oxen were mired up to their chests in the mud, and the man finally sat down himself and put his head dejectedly in his arms, looking as though he was going to weep.

I suspect that the uplands are better

suited to the cattle business than are these marshy lowlands to

agriculture. Indeed, the further west we move the more bovines we

encounter—a variety of cattle that is quite different from anything

I have ever seen back in Illinois, longer-legged, rangier, and

wilder, with long, gracefully arced horns. Yesterday we saw a

colorful sight—a herd of what must have been several thousand cows

being driven across the river by “cowboys.” The engineer had to

stop the train for fear of a collision with the beasts, thus giving

us a wonderful opportunity to observe the scene. Of course, I have

read about the cowboys in periodicals and I have seen artists’

renderings of them and now I find that they are every bit as

colorful and festive in the flesh. Martha blushed quite crimson at

the sight of them—a charming habit she has when excited—and an

exciting scene it was, too. The cowboys make a thrilling little

yipping noise as they drive their charges, waving their hats in the

air cheerfully. It all seems rather wild and romantic, with the

herd splashing across the river, urged along by these gay cowboys.

We are told by one of the soldiers that these men are on the way

from Texas to Montana Territory, where a prosperous new ranching

industry is springing up. Who knows, perhaps we “Indian brides”

will also visit that country in time—we have been forewarned that

the savages are a nomadic people, and that we are to be prepared

for frequent and sudden moves.

Today our train has been stopped for

several hours while a number of the men aboard indulge in a bit of

“sport”—the shooting of dozens of buffalo from the train windows. I

fail to see myself where exactly the sport in this slaughter lies

as the buffalo seem to be as stupid and trusting as dairy cows. The

poor dumb beasts simply mill about as they are knocked down one by

one like targets at a carnival shooting gallery, while the men

aboard, including members of our military escort, behave like

crazed children—whooping and hollering and congratulating

themselves on their prowess with the long gun. The women for the

most part are silent, holding handkerchiefs to their noses while

the train car fills with acrid smoke from the guns. It is a

grotesque spectacle and seems terribly wasteful to me—the animals

are left where they fall, many of those that aren’t killed

outright, mortally wounded and bellowing pitifully. Some of the

cows have newborn spring calves with them and these, too, are

cheerfully dispatched by the shooters. I have noticed during the

past day that the country we are passing through is littered with

bones and carcasses in various stages of decay and that a

noticeable stench of rotting flesh often pervades the air. Such an

ugly, unnatural thing can come to no good in God’s eyes or anyone

else’s for that matter. I can’t help but think once again what a

foolish, loutish creature is man. Is there another on earth that

kills for the pure joy of it?

Now we are finally under way again,

the bloodlust of the men evidently sated …

We have reached our first destination,

and are being lodged in officers’ homes while we await

transportation on the next leg of our journey. Martha and I have

been separated, and I am staying with the family of an officer

named Lieutenant James. His wife Abigail is tight-lipped and cool

and seems to have adopted the superior attitude with which those of

us enrolled in this program have been treated by virtually everyone

with whom we have come in contact since the beginning of our

journey. Although “officially” we are going among the heathens as

missionaries, everyone seems to know the real truth of our mission,

and everyone seems to despise us for it. Perhaps I am naive to

expect otherwise—that we might be accorded some measure of respect

as volunteers in an important social and political experiment but

of course small-minded souls like the Lieutenant’s wife must have

someone to look down upon, and so they have cast us in the role of

whores.

Shortly after our arrival, my hostess

knocked on the door to my room, and when I answered, refused to

enter but demanded in a haughty tone that I not speak of our

mission in front of her children at the dining table.

“As our mission is a secret one,” I

answered, “I had no intention of discussing it. May I ask why you

make such a request, madam?”

“The children have been exposed to the

drunken, degenerate savages who frequent the fort,” the woman

replied. “They are a filthy people whom I would not invite into my

home, let alone allow to sit at my dinner table. Nor will I permit