20. HEIL WIEN! HEIL BERLIN!

The century is fourteen years old, and so is Elisabeth, a serious young girl who is allowed to sit at dinner with the grown-ups. These are ‘men of distinction, high civil servants, professors and high-ranking officers in the army’ and she listens to the talk of politics, but is told not to talk herself unless she is talked to. She walks with her father to the bank each morning. She is building up her own library in her bedroom: each new book has a neat EE in pencil and a number.

Gisela is a pretty young girl of ten who enjoys clothes. Iggie is a boy of nine who is slightly overweight and self-conscious about it; he isn’t good at maths, but likes drawing very much indeed.

Summer arrives, and the children travel to Kövecses with Emmy. She has ordered a new costume, black with pleating to the blouse, for riding Contra, her favourite bay.

On Sunday 28th June 1914 the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Hapsburg Empire, is assassinated in Sarajevo by a young Serbian nationalist. On Thursday the Neue Freie Presse writes that ‘the political consequences of this act are being greatly exaggerated’.

On the following Saturday, Elisabeth writes a postcard to Vienna:

4th July 1914

Dearest Papa

Thank you so much for arranging about the Professors for next term. Today it was very warm in the morning so we could all go swimming in the lake but now it is colder and it may rain. I went to Pistzan with Gerty and Eva and Witold but I didn’t like it very much. Toni has had nine puppies, one has died and we have to feed them with a bottle. Gisela likes her new clothes. A thousand kisses.

Your Elisabeth

On Sunday 5th July the Kaiser promises German support for Austria against Serbia, and Gisela and Iggie write a postcard of the river at Kövecses: ‘Darling Papa, My dresses fit very well. We swim every day as it is so hot. All well. Love and kisses from Gisela and Iggie.’

On Monday 6th July it is cold at Kövecses and they don’t swim. ‘I painted a flower today. Love and heaps of kisses from Gisela.’

On Saturday 18th July mother and children return to Vienna from Kövecses. On Monday 20th July the British Ambassador, Sir Maurice de Bunsen, reports to Whitehall that the Russian Ambassador to Vienna has left for a fortnight’s holiday. That same day the Ephrussi leave for Switzerland: for their ‘long month’.

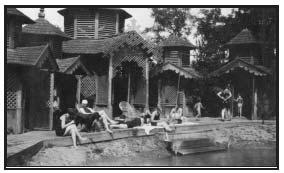

The bathing lake at Kövecses

The Russian imperial flag still flies from the boathouse roof. Viktor, worried that his son will grow up and have to do military service in Russia, has petitioned the Tsar to change his citizenship. This year Viktor has become a subject of His Majesty Franz Josef, the eighty-four-year-old Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary and Bohemia, King of Lombardy-Venetia, of Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, Galicia, Lodomeria and Illyria, Grand Duke of Tuscany, King of Jerusalem and Duke of Auschwitz.

On 28th July Austria declares war on Serbia. On 29th July the Emperor declares: ‘I put my faith in my peoples, who have always gathered round my throne, in unity and loyalty, through every tempest, who have always been ready for the heaviest sacrifices for the honour, the majesty, the power of the Fatherland.’ On 1st August Germany declares war on Russia. On the 3rd Germany declares war on France, and then the following day invades neutral Belgium. And the whole pack of cards falls: alliances are invoked and Britain declares war on Germany. On 6th August Austria declares war on Russia.

Mobilisation letters are sent out in all the languages of the Empire from Vienna. Trains are requisitioned. All Jules and Fanny Ephrussi’s young French footmen, careful around the porcelain and good at rowing on the lake, are called up. The Ephrussi are stuck in the wrong country.

Emmy travels to Zurich to enlist the help of the Austrian Consul General, Theophil von Jäger – a lover of hers – to get the household back to Vienna. There are a lot of telegrams. Nannies, maids and trunks need sorting out. The trains are too crowded and there is too much luggage, and the railway timetable – the implacable k & k railway, as certain as Spanish court ritual, as regular as the Vienna City Corps marching past the nursery window at half-past ten every morning – is suddenly useless.

There is cruelty in all of this. The French, Austrian and German cousins, Russian citizens, English aunts, all the dreaded consanguinity, all the territoriality, all that nomadic lack of love of country, is consigned to sides. How many sides can one family be on at once? Uncle Pips is called up, handsome in his uniform with its astrakhan collar, to fight against his French and English cousins.

In Vienna there is fervent support for this war, this cleansing of the country of its apathy and stupor. The British ambassador notes that ‘the entire people and press clamour impatiently for immediate and condign punishment of the hated Serbian race’. Writers join in the excitement. Thomas Mann writes an essay ‘Gedanken im Kriege’, ‘Thanks Be for War’ the poet Rilke celebrates the resurrection of the Gods of War in his Fünf Gesänge; Hofmannsthal publishes a patriotic poem in the Neue Freie Presse.

Schnitzler disagrees. He writes simply on 5th August: ‘World war. World ruin. Karl Kraus wishes the Emperor “a good end of the world”.’

Vienna was en fête: young men in twos and threes with sprigs of flowers in their hats on their way to recruit; military bands playing in the parks. The Jewish community in Vienna was cheerful. The monthly newsletter of the Austrian-Israelite Union, for July and August, declaimed: ‘In this hour of danger we consider ourselves to be fully entitled citizens of the state…We want to thank the Kaiser with the blood of our children and with our possessions for making us free; we want to prove to the state that we are its true citizens, as good as anyone…After this war, with all its horrors, there cannot be any more anti-Semitic agitation…we will be able to claim full equality.’ Germany would free the Jews.

Viktor thought otherwise. It was a suicidal catastrophe. He had dustsheets put over all the furniture in the Palais, sent the servants home on board wages, sent the family to the house of Gustav Springer, a friend, near Schönbrunn, then on to cousins in the mountains near Bad Ischl, and took himself to the Hotel Sacher to see out the war with his books on history. There is a bank to run, something that is difficult when you are at war with France (Ephrussi et Cie, rue de l’Arcade, Paris 8), England (Ephrussi and Co., King Street, London) and Russia (Efrussi, Petrograd).

‘This Empire’s had it,’ says the Count in Joseph Roth’s novel The Radetzky March:

As soon as the Emperor says goodnight, we’ll break up into a hundred pieces. The Balkans will be more powerful than we will. All the peoples will set up their own dirty little statelets, and even the Jews will proclaim a king in Palestine. Vienna stinks of the sweat of democrats, I can’t stand to be on the Ringstrasse any more…In the Burgtheater, they put on Jewish garbage, and they ennoble one Hungarian toilet-manufacturer a week. I tell you, gentlemen, unless we start shooting, it’s all up. In our lifetime, I tell you.

There were lots of proclamations that autumn in Vienna. Now that the war is properly under way, the Emperor addresses the children of his Empire. The newspapers print ‘Der Brief Sr. Majestät unseres allergnädigsten Kaisers Franz Josef I an die Kinder im Weltkriege’, a letter from His Majesty, our all-loving Franz Josef I, to the children in the time of the World War: ‘You children are the jewels of all the peoples of mine, the blessing of their future conferred a thousand times.’

After six weeks Viktor realises the war is not going to end and returns from the Hotel Sacher. Emmy and the children are eventually brought back from Bad Ischl. The dustcovers are taken off the furniture. There is a lot of activity in the street outside the nursery window. There is so much noise from the demonstrating students – Musil notes ‘the ugliness of the singing in the cafés’ in his journal – from the marching soldiers, with their bands, that Emmy considers moving the children’s rooms altogether to a quieter part of the house. This does not happen. The house is poorly designed for families, she says – we are all on show here in one glass box, we might as well be living on the street itself, for all that your father does about it.

The students’ chants change week by week. They start with ‘Serbien muss sterben!’, ‘Serbia must die!’ Then the Russians get it: ‘One Round, One Russian!’ Then the French. And it gets more colourful by the week. Emmy is worried by the war of course, but she is also worried by the effect of all this shouting on the children. They have their meals now on a little table in the music room, which opens onto the Schottengasse and is a bit quieter.

Iggie attends the Schottengymnasium. This is a very good school run by the Benedictines round the corner, one of the two best schools in Vienna, he told me. The plaque on the wall that lists famous former poets indicates this. Though the teachers are Brothers, many of the pupils are Jewish. The school lays particular stress on the Classics, but there are also mathematics, algebra, calculus, history and geography classes. Languages are studied as well. Learning these is irrelevant for these three children, who switch between English and French with their mother and German with their father. They know only a smattering of Russian and No Yiddish. The children are told to speak only German outside the house. All foreign-sounding shops in Vienna have had their names pasted over by men on ladders.

Girls are not taught at the Schottengymnasium. Gisela is taught at home by her governess in the schoolroom, next to Emmy’s dressing-room. Elisabeth has negotiated with Viktor and now has a private tutor. Emmy is opposed to this. She is so angry about this inappropriate, complicated arrangement for her daughter that Iggie hears her shouting and then breaking something, possibly porcelain, in the salon. Elisabeth scrupulously follows the same curriculum as the one boys her age are taught at the Schotten - gymnasium, and is allowed to go to the school laboratory in the afternoons and have a lesson by herself with one of the teachers. She knows that if she wants to go to the university, then she has to pass the final examination from this school. Elisabeth has known since she was ten that she must get from this room, her schoolroom with its yellow carpet, across the Franzenring to that room, the lecture hall of the university. It is only 200 yards away – but for a girl, it might as well be a thousand miles. There are more than 9,000 students this year, and just 120 of them are female. You can’t see into the hall from Elisabeth’s room. I’ve tried. But you can see its window, and imagine the tiered seating and a professor leaning over the lectern at the front. He is talking to you. Your hand moves in a dream across your notes.

Iggie attends the Schottengymnasium reluctantly. You can run there in three minutes, though I haven’t tried this with a satchel. There is a class photograph from 1914, third form: thirty boys in grey-flannel suits with ties, or sailor suits, leaning on their desks. Two windows are open onto the five-storey central courtyard. There is one idiot pulling faces. The teacher is implacable at the back in his monastic robes. On the reverse of the photograph are all their signatures – all the Georgs, Fritzs, Ottos, Maxs, Oskars and Ernsts. Iggie has signed in a beautiful italic hand: Ignace v. Ephrussi.

On the back wall is a blackboard scrawled over with geometry proofs. Today they have been studying how to work out the surface area of a cone. Iggie comes home each day with homework. He detests it. He is poor at algebra and calculus and hates mathematics. Seventy years on, he could give me the names of each Brother and what they tried unsuccessfully to teach him.

And he comes home with rhymes:

Heil Wien! Heil Berlin!

In 14 Tagen

In Petersburg drinn’!

(Hail Vienna! Hail Berlin!

In 14 days

We’ll be in Petersburg!)

There are ruder ones than this. These do not go down well with Viktor, who loves St Petersburg and is Russian-born, though he is now, of course, Austrian and loves Vienna.

For Iggie, the war means playing soldiers. It is their cousin Piz – Marie-Louise von Motesiczky – who proves to be a particularly good soldier. There is a servants’ staircase in the corner of the Palais, tucked away behind a false door. It is a wide nautilus spiral of 136 steps that goes up to the roof and, if you pull the door towards you, then you are suddenly above the caryatids and acanthus leaves and you can see everything, the whole of Vienna. Turn slowly clockwise from the university, then the Votivkirche, then St Stephen’s, all the way back through the towers and domes of the Opera and Burgtheater and Rathaus to the university again. And you can dare each other to crawl right up to the edge of the parapet and peer down through the glass into the courtyard below, or you can shoot all the tiny scurrying burghers and their ladies in the Franzensring or in the Schottengasse. For this you use cherry stones and a roll of stiff paper and a good blow. There is a café directly below with wide canvas awnings, which is a particularly appealing target. The waiters in their black aprons look up and shout, and you have to dodge.

And you can climb onto the roofs of the Liebens’ Palais next door, where more cousins live.

Or you are spies and can go down the staircase into the cellars – barrel-vaulted – where there is a tunnel that takes you all the way across Vienna to Schönbrunn. Or all the way to the Parliament. Or into the other secret tunnels that you have been told about, a network that you can get into from the advertising kiosks on the Ringstrasse. This is where the Kanalstrotter are meant to live – furtive, shadowy people who exist on the coins that drop from pockets through the gratings in the pavements.

The household and the family make their sacrifices during the war. In 1915 uncle Pips is serving as an imperial liaison officer with the German high command in Berlin, where he has been instrumental in helping Rilke get a desk job away from the front. Papa is fifty-four and exempt. The manservants in the Palais have disappeared, apart from the butler Josef, who is too old to be called up. A small bevy of maids is kept on and a cook and Anna, who has now been with the family for fifteen years and seems to be able to anticipate everyone’s needs and has an ability to calm tempers. She knows everything. There are no secrets from your maid, when you come back home after luncheon and need to change your day-dress.

The house is a lot quieter these days. Viktor used to invite friends of the servants who were between positions to come on Sunday and share the midday meal of boiled and roast meats. This no longer happens: the servants’ hall is in ebb. There are no grooms or coachmen, no carriage-horses, so if you want to go to the Prater you take one of the fiacres from the stand in the Schottengasse or even go by tram. There are ‘no parties’. This actually means that there are far fewer parties, and that the parties are different. You cannot be seen in a ball dress, but you can still go out to dinner and to the Opera. In her memoir Elisabeth writes that ‘Mama entertained at tea only, and played bridge.’ Demel still sells its cakes, but you must not be seen to have too many on display at your at-homes.

Emmy still dresses up every evening, because it is important not to let standards slip. Herr Schuster is unable to make his annual visit to Paris to buy gowns for his baroness, but Anna knows her so well that she is adept at managing the wardrobe and reworking gowns with assiduous study of the latest journals. There is a photograph of Emmy this spring. She is wearing a very long black gown and a sort of black bearskin pillbox hat – a colback – with a white egret feather and a rope of pearls to her waist, and if there wasn’t a date on the back you wouldn’t believe that Vienna was at war. I wonder if this is a last-season dress and how I could possibly find out.

As ever, Gisela and Iggie come and talk to Emmy in her dressing-room in the evening. They are allowed to unlock the vitrine themselves. You don’t play with the netsuke on the carpet if you are a girl of ten and a boy of eight, as that is rather childish, but you still reach deep into the glass to find the bundle of kindling and the puppies, if it has been a bad day and you have been shouted at by Brother Georg.

There are many, many people on the streets. There are Jews – 100,000 refugees just from Galicia alone – who have been driven out in terrible mass expulsions by the Russian army. Some are put up in barracks where there are basic amenities, but these are inadequate for families. Many find their way into Leopoldstadt and live in appalling conditions. Many are begging. They are not pedlars with a scant tray of postcards and ribbons. They have nothing to sell. The Israelitische Kultusgemeinde, IKG, organises relief efforts.

The more assimilated Jews worry about these newcomers: they are felt to be rather vulgar in their manners; their speech and dress and customs are not aligned to the Bildung of the Viennese. There is anxiety about whether they will impede assimilation. ‘It is terribly hard to be an Eastern Jew; there is no harder lot than that of the Eastern Jew newly arrived in Vienna,’ writes Joseph Roth about these Jews. ‘No-one will do anything for them. Their cousins and coreligionists, with their feet safely pushed under desks in the First District, have already gone “native”. They don’t want to be associated with Eastern Jews, much less taken for them.’ Maybe, I think, this is anxiety from the recently arrived towards the very newly arrived. They are still in transit.

The streets are different. The Ringstrasse is meant for strolling along. It is meant for chance encounters, casual cups of coffee outside the Café Landtmann, hailing friends, hoped-for assignations on the Corso. It is an easy stream of flowing people.

But Vienna now seems to have two speeds. One is the pace of marching soldiers, children racing alongside, and the other is standstill. You notice that there are people queuing outside the shops for food, for cigarettes, for news. Everyone talks of this phenomenon of Anstellen, standing in line. The police note when queues start for different commodities. In the autumn of 1914 it is for flour and bread. In early 1915 it is milk and potatoes. In autumn 1915 it is oil. In March 1916 it is coffee. The next month it is sugar. The next month it is eggs. In July 1916 it is soap. Then it is everything. The city is sclerotic.

The circulation of things in the city is changing, too. There are stories of hoarding, rich men with rooms stacked high with boxes and boxes of food. There is profiteering, according to the rumours, by ‘coffee-house types’. The only people who are doing well are those with food, these ‘types’, or farmers. To get food, you part with more and more. Objects are loosened from your home and become currency. There are stories about farmers wearing the tailcoats of the Viennese bourgeois, of their wives in silk gowns. Farmhouses are stuffed with pianos, porcelain and bibelots and Turkish carpets. Piano teachers, say the rumours, are moving out of Vienna to follow their new pupils into the country.

The parks are different. There are fewer park keepers and sweepers. The man who waters the paths first thing, in the park across the Ring, is no longer there. The paths have always been dusty, but now are dustier.

Elisabeth is almost sixteen. She is now allowed to get her books bound in half-morocco with marbled covers when Viktor gets his books bound for the library. This is a rite of passage, a way of marking that her reading has significance. It is a way of simultaneously separating her books from her father’s – these go into my library, these into yours – and joining them together. On visits home from Berlin, uncle Pips gives her a job of copying out letters for him from his theatre director friend, Max Reinhardt.

Gisela is eleven and starts drawing lessons in the morning-room. She is very good. Iggie is nine and is not allowed in. He knows the uniforms of imperial regiments (‘pale blue trousers of the infantry, the blood red fezzes on the heads of the pale blue Bosnians’) and sketches the colours of their tunics in his little leather notebooks tied up with purple silk. In the dressing-room, with the cabinet of netsuke forgotten, Emmy calls him her adviser on dress.

He starts to draw dresses. Furtively.

Iggie writes a story in an octavo Manila book with a boat on the cover. It is February 1916.

Fisherman Jack. A story by I.L.E.

Dedication. To darling Mama this little volume is very lovingly dedicated.

Preface. This story is not perfect in any way, I am sure, but one thing is well done, I think: I have described the characters of the book clearly.

Chap. 1. Jack and his life. Jack had not been a fisherman all his short life, at least not until his father died…

In March the IKG writes an open letter to the Jews of Vienna: ‘Jewish Fellow Citizens! In fulfilment of their obvious duty, our fathers, brothers and sons devote their blood and their lives as brave soldiers in our glorious army. With similar consciousness of duty, those who remain at home also have happily sacrificed their property on the altar of their beloved fatherland. Thus now again the call of the state should arouse a patriotic echo in all of us!’ The Jews of Vienna contribute another 500,000 crowns to the war loans.

Rumours are endemic. Kraus: ‘What do you say about the rumours?/I’m worried./The rumour circulating in Vienna is that there are rumours circulating in Austria. They’re even going from mouth to mouth, but nobody can tell you.’

In April in Vienna a group of soldiers on leave, survivors of the battle of Uscieczko, appear on the stage of a Viennese theatre and re-enact the events of the battle. Kraus, splenetic at this reduction of real events to spectacle, lets fly with an attack on the increasing theatricality of the war. The problem is: ‘die Sphären fliessen ineinander’ – the spheres have become blurred, flow together. Boundaries are indistinct in Vienna during the war.

This means that there is plenty for the children to see. Their balcony is a splendid vantage point.

On 11th May Elisabeth goes to the Opera to hear Wagner’s Die Meistersinger with her cousin. ‘Heilige Deutsche Kunst’ – ‘sacred German art’ – she writes in her little green book in which she records the concerts and theatres she attends. She patriotically underlines Deutsche.

In July the children are taken by Viktor to the Vienna War Exhibition in the Prater. This has been organised to focus the war effort at home: it will raise morale and money. Best of all is a dog show in which army Dobermans go through their routines. There are numerous display halls in which the children can see captured artillery pieces. There is a realistic mountain panorama of a battle site, so that they can imagine the boys fighting on the borders with Italy. There are concerts given by soldiers who have lost their limbs, tuba-players with prosthetic legs. As you leave, there is a cigarette room in which you can donate tobacco for the soldiers.

Elisabeth’s opera and theatre notebook, 1916

There is the first showing of a true-to-life trench. It is advertised, notes Kraus acidly, as showing ‘life in the trenches with striking realism’.

On 8th August, staying at Kövecses, Elisabeth is given a dark-green book of poems written by her maternal grandmother Evelina, first published in Vienna in 1907. It is inscribed by her: ‘These old songs have faded away from me. Since they are resonating for you, they also resonate to me again.’

Viktor is doing his bit at the bank, a thankless task in wartime, with most of the young, competent men away at the front. He is generous and patriotic in his financial support. He buys lots of government war bonds. Then he buys some more. Though he is advised by Gutmann and other friends at the Wiener Club to move his money to Switzerland, as they are doing, he will not so. It would be unpatriotic. At dinner he moves his hand over his face, brow to chin, as he says that in every crisis there are opportunities for those who look for them.

When Viktor arrives home, he spends more time in his study. ‘A library,’ he says, quoting Victor Hugo, ‘is an act of faith.’ Fewer books arrive for him: nothing from Petersburg, Paris, London, Florence. He is disappointed in the quality of a volume sent from a new dealer in Berlin. Who knows what he is reading in there, smoking his cigars? Sometimes a supper tray is prepared and taken in. Things are not so good between him and Emmy, and the children hear her raised voice more often.

Before the war every summer there was an operation with ladders and buckets and mops over the courtyard roof. Because there are no manservants, the glass over the courtyard has not been cleaned for two years. The light coming in is greyer than ever before.

Boundaries become indistinct. As a child, your patriotism is simultaneously unequivocal and confused. On the streets and at school you hear of ‘British envy, French thirst for revenge and Russian rapacity’. Where you can go diminishes by the month, for all the family networks are in suspension. There are letters, but you cannot see your English or French cousins, cannot travel as you used to.

In the summer the family cannot go to the Chalet Ephrussi in Lucerne, so they go to Kövecses for the whole long holiday. This means that at least they can eat properly. There is roast hare, game pies and plum dumplings, to be eaten hot mit Schlag, with whipped cream. In September there is a shooting party, when cousins who are on leave from the shooting at the Front come to shoot partridge.

On 26th October the prime minister, Count Karl von Stürgkh, is assassinated in a restaurant at the Hotel Meissel & Schadn on Kärntner Strasse. There are two points of general interest. First, that his assassin is the radical socialist Fritz Adler, son of the Social Democrat leader Viktor Adler. Second, that he had eaten a lunch of mushroom soup, boiled beef with mashed turnips and a pudding. He had been drinking a wine spritzer. There is an ancillary point of interest that excites the children greatly: it is at this very restaurant that they had eaten Ischler Torte, chocolate cake with almond and cherry filling, with their parents earlier in the summer.

On 21st November 1916 Franz Josef I dies.

All the newspapers have black borders: Death of our Emperor, Kaiser Franz Josef, The Emperor – dead! Several have engravings of him with his characteristic mistrustful look. The Neue Freie Presse carries no feuilleton. The Wiener Zeitung has the most satisfyingly graphic response, a death-notice on a blank white page. All the weeklies follow suit, apart from Die Bombe, which has a picture of a girl surprised in her bed by a gentleman.

Franz Josef was eighty-six and had been on the throne since 1848. On a wintry day there is a massive funeral cortège through Vienna. The streets are lined with soldiers. His coffin is on a hearse pulled by eight horses with black plumes. On either side march aged archdukes with chests of medals and representatives of all the imperial guards. Behind him walk the young, new Emperor Karl and his wife Zita, in a veil to the ground, and between them their four year-old son Otto wearing white with a black sash. The funeral takes place in the cathedral with the kings of Bulgaria, Bavaria, Saxony and Württemberg present, fifty archdukes and duchesses and forty other princes and princesses. Then the cortège winds its way to the Capuchin church in the Neue Markt close to the Hofburg palace. The destination is the Kaisergruft, the imperial tomb. There is the drama of admittance to the church – the guards knock three times and are refused twice – and then Franz Josef is buried between his wife Elisabeth and his long-dead eldest son, the suicide Rudolf.

The children are taken to the Meissel & Schadn Hotel on a corner of Kärntner Strasse, where they had that delicious cake, to watch the cortège from a first-floor window. It is extremely cold.

Viktor remembers the Makart spectacle with all the floppy hats with plumes, thirty-seven years before; his father being ennobled, forty-six years previously. It is a generation since Franz Josef opened the Ringstrasse, the Votivkirche, the Parliament, the Opera House, the City Hall, the Burgtheater.

The children think about all the other processions that the Emperor has taken part in, the countless times they have seen him in his carriage in Vienna and in Bad Ischl. They remember him riding with Frau Schratt, his companion, when she waved to them, a small discreet wave from a gloved right hand. They remember the family joke to be repeated after visiting grim great-aunt Anna Herz von Hertenreid, the witch. When you have got safely away from her and her questioning, you have to repeat the Emperor’s old saying ‘Es war sehr schön, es hat mich sehr gefreut’ – It has been very nice, I’ve enjoyed myself – before anyone else can say it.

In early December there is a serious meeting in the dressing-room. Elisabeth is to be allowed to choose the style of her own dress for the first time. She has had many dresses made for her before, but this is the first time she is allowed to make the decisions. This is a moment that has been much anticipated by Emmy and Gisela and Iggie, all of whom love clothes, and by Anna, who looks after them. In the dressing-room on the dressing-table is a book of swatches of fabrics and Elisabeth comes up with an idea for a dress that has a spider’s-web pattern over the bodice.

Iggie is absolutely appalled. Seventy years later in Tokyo he recounts how there was complete silence when she described what she wanted: ‘She simply had no taste at all.’

On 17th January 1917 there is a new edict, which states that the names of convicted profiteers will be printed in a list in the newspaper and on notice-boards in home districts. There has been some pressure to bring back the stocks. There are many names for profiteer, but increasingly they elide: hoarder, usurer, Ostjude, Galician, Jew.

In March Emperor Karl institutes a new school holiday to be held on 21st November to commemorate the passing of Franz Josef and his own ascension to the throne.

In April Emmy goes to a reception at Schönbrunn given for a committee of women who organise something to do with widows of soldiers who have fallen in defence of the Empire. It is unclear to me exactly what is going on. But there is a splendid photograph of this gathering of a hundred women in their best in the State Ballroom, a great arc of hats under the rococo plasterwork and mirrors.

In May there is an exhibition of 180,000 toy soldiers in Vienna. All summer everything in the city is helden, heroic. All year there are white spaces in the newspapers where the censors have struck out information or comment.

The corridor between Emmy’s dressing-room, the room with the netsuke, and Viktor’s dressing-room seems to get longer and longer. Sometimes Emmy does not appear at the dining-table at one o’clock and her place has to be removed by a maid while everyone pretends not to notice. Sometimes it is removed again at eight o’clock.

Food is an increasing problem. There have been queues for bread and milk and potatoes for two years, but there are now queues for cabbage and plums and beer. Housewives are exhorted to use their imaginations. Kraus pictures an efficient Teutonic wife: ‘Today we were well provided for…There were all kinds of things. We had a wholesome broth made with the Excelsior brand of Hindenburg cocoa-cream soup cubes, a tasty ersatz false hare with ersatz kohlrabi, potato pancakes made of paraffin…’ Coins change. Before the war, gold kronen were minted, or silver ones. After three years of war they are copper. This summer they are iron.

Emperor Karl receives fervent acclaim in the Jewish press. The Jews, says Bloch’s Wochenschrift, are ‘not only the most loyal supporters of his empire, but the only unconditional Austrians’.

In the summer of 1917 Elisabeth stays in Altaussee at the country house of Baroness Oppenheimer with her best friend Fanny. Fanny Loewenstein has spent her childhood living all over Europe and speaks the same run of languages as Elisabeth. They are both seventeen and very keen on poetry: they write constantly. To their great excitement, both the poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal and the composer Richard Strauss are staying too, as are Hofmannsthal’s two sons. The other house-guests include the historian Joseph Redlich, who, Elisabeth wrote sixty years later, ‘impressed us very unfavourably with his predictions of the impending defeat of Austria and Germany while Fanny and I still believed the official communiqués of a victorious outcome’.

In October the Reichspost claims that there is an international conspiracy against Austria-Hungary and that Lenin and Kerensky and Lord Northcliffe are all Jews. President Woodrow Wilson is also acting ‘under the influence’ of the Jews.

On 21st November, the anniversary of the late Emperor’s demise, all schoolchildren get a day off.

In the spring of 1918 things are very difficult indeed. Emmy, ‘the dazzling centre of a distinguished society circle’, according to Kraus in Die Fackel, is more dazzling than ever. She has a new lover, a young count in one of the cavalry regiments. This young count is the son of family friends, a regular guest at Kövecses, where he brings his own horses. He is also extremely good-looking and is far closer to Emmy in age than to Viktor.

In the spring a book is published for the schoolchildren of the Empire, Unser Kaiserpaar. It describes the new Emperor and his wife and son at the funeral of Franz Josef. ‘The illustrious parental couple arranged it that their first-born child was introduced at the hand of his mother. From this picture arose quite magically a bond of understanding between the ruling pair and the people: the tender gesture of the mother captivated the empire.’

On 18th April Elisabeth and Emmy go to see Hamlet at the Burgtheater with the impossibly handsome Alexander Moissi in the title role. ‘Der grösste Eindruck meines Lebens’ – the most impressive thing in my life – Elisabeth notes in her green notebook. Emmy is thirty-eight and two months pregnant.

It is in this spring that there is good family news. Both Emmy’s younger sisters are engaged to be married. Gerty, twenty-seven, is to be married to Tibor, a Hungarian aristocrat with the family name of Thuróczy de Alsó-Körösteg et Turócz-Szent-Mihály. Eva, twenty-five, is to be married to Jenö, the less fantastically named Baron Weiss von Weiss und Horstenstein.

In June there is a wave of strikes. The flour ration is now just 35 grams a day, enough to fill a coffee-cup. Numerous bread trucks are ambushed by large crowds of women and children. In July milk disappears. It is meant to be saved for nursing mothers and the chronically sick, but even they find it difficult to get hold of. Many Viennese can only survive by foraging for potatoes in the fields outside the city. The government debates the carrying of rucksacks. Should city dwellers be allowed to carry them? If they do, should they be searched at the rail stations?

There are rats in the courtyard. These are not ivory rats with amber eyes.

There are also increasing numbers of demonstrations against the Jews. On 16th June there is a German People’s Assembly that meets in Vienna to swear fealty to the Kaiser and reaffirm the goal of pan-German unity. One speaker has a solution to the problems: a pogrom to heal the wounds of the state.

On 18th June the prefect of police asks permission of Viktor to station men in the courtyard of the Palais, where the car stands, unused for want of petrol. The police will be on hand in the case of unrest, but out of sight. Viktor agrees.

Desertions multiply. More of the Hapsburg army surrender than want to fight: 2,200,000 soldiers are taken prisoner. This is seventeen times the number of British soldiers who are prisoners of war.

On 28th June Elisabeth receives her end-of-year report from the Schottengymnasium. Seven ‘sehr gut’s for religious study, German, Latin, Greek, geography and history, philosophy and physics. One ‘gut’ for mathematics. On 2nd July she gets her matriculation certificate, stamped with the head of the old Emperor. The printed word ‘he’ is crossed out and ‘she’ has been inscribed in blue ink.

It is hot. Emmy is five months pregnant, with the summer ahead of her. A baby will be loved and cherished, of course – but the bother of it.

August in Kövecses. There are only two old men to tend the gardens, and the roses on the long veranda are unkempt. On 22nd September Gisela, Elisabeth and aunt Gerty go to hear Fidelio at the Opera. On 25th they go to see Hildebrand at the Burgtheater and Elisabeth notes the Archduke in the audience. Brazil declares war on Austria. On 18th October the Czechs seize Prague, renounce the rule of the Hapsburgs and declare independence. On 29th October Austria petitions Italy for an armistice. On 2nd November at ten in the evening there is news that there has been a breakout of violent Italian POWs from an internment camp outside Vienna and that they are swarming into the city. At 10.15 the news becomes more graphic – there are 10,000 or 13,000 of them, and they have been joined by the Russian prisoners. Messengers start appearing in the cafés along the Ringstrasse ordering officers to report to police headquarters. Many do so. Two officers shout to those leaving the Opera to return home and lock their doors. At eleven o’clock the police chief consults with the military about defending Vienna. By midnight the Minister of the Interior announces that reports have been greatly exaggerated. By dawn it is admitted that it was another rumour.

On 3rd November the Austro-Hungarian Empire is dissolved. The next day Austria signs the armistice with the Allies. Elisabeth goes to the Burgtheater and sees Antigone with cousin Fritz von Lieben. On 9th November Kaiser Wilhelm abdicates. On 12th November Emperor Karl flees to Switzerland, and Austria becomes a republic. There are crowds surging past the Palais all day, many with red flags and banners, converging on the Parliament.

On 19th November Emmy gives birth to a son.

He is blond and blue-eyed and they call him Rudolf Josef. It is difficult to think of a more elegiac name to give a boy just as the Hapsburg Empire crashes around them.

It is very, very difficult. The influenza is raging, and there is no milk to be had. Emmy is ill: it is twelve years since Iggie was born, eighteen years since her first child. Being pregnant during a war is not easy. Viktor is fifty-eight and surprised by fatherhood again. Amongst all the complexities and the surprise at this little boy being born – and these complexities are manifold – Elisabeth is mortified to find that most people think the baby is hers. She is eighteen after all, and her mother and grandmother had children early. There are rumours. The Ephrussi are keeping up appearances.

In her short memoir of the period she writes of the unrest, ‘I remember very little of the details, only our great anxiety and fear.’

But, ‘Meanwhile,’ she adds in the final, triumphant line, ‘I had registered at the university.’ She had escaped. She had made it from one side of the Ringstrasse to the other.