17. THE SWEET YOUNG THING

Elisabeth’s memoir is a tonic: twelve unsentimental pages written for her sons in the 1970s. ‘The house I was born in stood, and still stands, outwardly unaltered, on the corner of the Ring…’ She gives details of the running of the household, she gives the names of the horses, and she walks me through the rooms in the Palais. Finally, I think, I will find out where Emmy has hidden the netsuke.

If Emmy turns right out of the nursery and goes along the corridor she enters the sides of the courtyard with the kitchens and sculleries, the pantry and the silver-room – where the light burns all day – and then on to the butler’s room and the servants’ hall. At the end of this corridor are all the maids’ rooms, rooms whose windows open only into the courtyard, some yellow light filtering in through the glassed roof, but no fresh air. Her maid Anna’s room is down there somewhere.

When Emmy turns left she is in her drawing-room. She has hung it with pale-green silk brocade. The carpets are a very pale yellow. Her furniture is Louis XV, chairs and fauteuils of inlaid woods with bronze mounts and fat striped silk cushions. There are occasional tables, each with their little set-piece of bibelots, and a larger table on which she could perform the intricacies of making tea. There is a grand piano that is never played and a Renaissance Italian cabinet with folding doors, painted on the inside, and very small drawers that the children aren’t meant to play with, but do. When Elisabeth reached between the tiny gilded twisty columns on either side of an arch and pressed upwards, a tiny secret drawer came out with an exhaled breath.

There is light in these rooms, trembling reflections and glints of silver and porcelain and polished fruitwood, and shadows from the linden trees. In the spring flowers are sent up each week from Kövecses. It is a perfect place to display a vitrine with cousin Charles’ netsuke, but they are not here.

On from the drawing-room is the library, the largest room on this floor of the Palais. It is painted black and red, like Ignace’s great suite of rooms on the floor below, with a black-and-red Turkish carpet and huge ebony bookshelves lining the walls and large tobacco-coloured leather armchairs and sofas. A large brass chandelier hangs over an ebony table inlaid with ivory flanked by the pair of globes. This is Viktor’s room, thousands of his books running over the walls, his Latin and Greek histories and his German literature and his poetry and his lexicons. Some of the bookcases have a fine golden mesh over them and are locked with a key that he keeps on his watch chain. Still no vitrine.

And on from the library is the dining-room, with walls covered in Gobelin tapestries of the hunt, bought by Ignace in Paris, and windows overlooking the courtyard, but with the curtains drawn, so that the room is in perpetual gloom. This must be the dining table where the gold dinner service is set out, each plate and bowl engraved with ears of corn and a double Ephrussi E slap-bang in the middle, the boat with its puffed-out sails skimming across a golden sea.

The gold dinner service must have been Ignace’s idea. His furniture is everywhere. Renaissance cabinets, carved baroque chests, a huge Boulle desk that could only be kept in the ballroom downstairs. His pictures are everywhere, too. Lots of Old Masters, a Holy Family, a Florentine Madonna. There are seventeenth-century Dutch pictures by some quite good artists: Wouwermans, Cuyp, something after Frans Hals. There were also lots and lots of Junge Frauen, some by Hans Makart; interchangeable young ladies in interchangeable frocks in rooms surrounded by ‘velvets, carpets, genius, panther skins, knickknacks, peacock feathers, chests, and lutes’ (Musil in acidic mood). All of them framed in heavy gold or heavy black. No Parisian vitrine full of netsuke amongst these pictures, this spectacular, theatrical display, this treasure-house.

Everything here, each grandiloquent picture and cabinet, seems immovable in the light that filters in from the glassed-in courtyard. Musil understood this atmosphere. In great old houses there is a muddle where hideous new furniture stands carelessly alongside magnificent old, inherited pieces. In the rooms of the Palais belonging to the ostentatious nouveaux riches, everything is too defined, there is ‘some hardly perceptible widening of the space between the pieces of furniture or the dominant position of a painting on a wall, the tender, clear echo of a great sound that had faded away’.

I think of Charles with all his treasures, and know that it was his passion for them that kept them moving. Charles could not resist the world of things: touching them; studying them; buying them; rearranging them. The vitrine of netsuke that he has given to Viktor and Emmy made a space in his salon for something new. He kept his rooms in flux.

The Palais Ephrussi is the exact opposite. Under the grey-glassed roof, the whole house is like a vitrine that you cannot escape.

At either end of the long enfilade are Viktor and Emmy’s private rooms. Viktor’s dressing-room has his cupboards and chests of drawers and a long mirror. There is a life-size plaster bust of his tutor, Herr Wessel, ‘whom he had very much loved. Herr Wessel had been a Prussian and a great admirer of Bismarck and of all things German.’ The other great thing in the room, never discussed, is a very large – and highly unsuitable – Italian painting of Leda and the Swan. In her memoir Elisabeth wrote that she ‘used to stare at it – it was huge – every time I went in to see my father change into a stiff shirt and dinner jacket for going out in the evening, and could never discover what the objection might be’. Viktor has already explained that there is no space for knick-knacks here.

Emmy’s dressing-room is at the other end of the corridor, a corner room with windows looking out across the Ring to the Votivkirche and onto the Schottengasse. It has the beautiful Louis XVI desk given to the couple by Jules and Fanny, with its gently bowed legs with ormolu mounts ending in gilt hooves, and drawers that are lined with soft leather in which Emmy keeps her writing paper and letters tied up in ribbons. And she has a full-length mirror hinged in three parts so that she can see herself properly when dressing. It takes up most of the room. And a dressing-table and washstand with a silver-rimmed glass basin and a matching glass jug with a silver top.

And here at last we find the black lacquer cabinet – ‘as tall as a tall man’ in Iggie’s memory – with its green velvet-lined shelves. Emmy has put the vitrine in her dressing-room, with its mirrored back and all 264 netsuke from cousin Charles. This is where my brindled wolf has ended up.

This makes so much sense, and yet it makes no sense at all. Who comes into a dressing-room? It is hardly a social space, and certainly not a salon. If the boxwood turtles and the persimmon and the cracked little ivory of the girl in her bath are kept here on their green velvet shelves, this means that they do not have to be explained at Emmy’s at-homes. They do not have to be mentioned at all by Viktor. Could it be embarrassment that brings the vitrine here?

Or was the decision to take the netsuke away from the public gaze intentional, away from all that Makart pomposity; putting them into the one room that was completely Emmy’s own because she was intrigued by them? Was it to save them from the dead hand of Ringstrassenstil? There was not much in these Ephrussi parade grounds of gilt furniture and ormolu that you might want to have near you. The netsuke are intimate objects for an intimate room. Did Emmy want something that was simply – and literally – untouched by her father-in-law Ignace? A little bit of Parisian glamour?

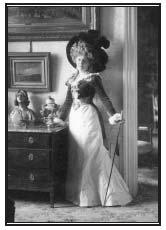

This is her room. She spent a great deal of time in it. She changed three times a day – sometimes more. Putting on a hat to go to the races, with lots of little curls pinned one by one to the underside of the hat’s wide brim, took forty minutes. To put on the long embroidered ballgown with a hussar’s jacket, intricate with frogging, took for ever. There was dressing up for parties, for shopping, dinner, visiting, riding to the Prater and balls. Each hour in this dressing-room was a calibration of corset, dress, gloves and hat with the day, the shrugging-off of one self and the lacing into another. She has to be sewn into some dresses, Anna, kneeling at her feet, producing thread, needle, thimble from the pocket of her apron. Emmy has furs, sable trimming to a hem, an arctic fox around her neck in one photograph, a six-foot stole of bear looped over a gown in another. An hour could pass with Anna fetching different gloves.

Emmy and an archduke, Vienna, 1906

Emmy dresses to go out. It is winter 1906 in a Viennese street and she is talking to an archduke. They are smiling as she hands him some primroses. She is wearing a pin-striped costume: an A-line skirt with a deep panel at the hem cut across the grain and a matching close-cut Zouave jacket. It is a walking costume. To dress for that walk down Herrengasse would have taken an hour and a half: pantalettes, chemise in fine batiste or crêpe de Chine, corset to nip in the waist, stockings, garters, button boots, skirt with hooks up the plaquette, then either a blouse or a chemisette – so no bulk on her arms – with a high-stand collar and lace jabot, then the jacket done up with a false front, then her small purse – a reticule – hanging on a chain, jewellery, fur hat with striped taffeta bow to echo the costume, white gloves, flowers. And no scent; she does not wear it.

The vitrine in the dressing-room is sentinel to a ritual that took place twice a year in spring and autumn, the ritual of choosing a wardrobe for the coming season. Ladies did not go to a dressmaker to inspect the new models; the models were brought to them. The head of a dressmaker’s would go to Paris and select gowns that came carefully packed in several huge boxes, with an elderly, white-haired, black-suited gentleman, Herr Schuster. His boxes were piled up in the passage, where he sat with them; they were carried into Emmy’s dressing-room one by one by Anna. When Emmy was dressed, Herr Schuster was ushered in for pronouncement. ‘Of course he always approved, but if he found Mama inclined to favour one of them to the extent of wanting to try it on again, he waxed ecstatic, saying that the dress absolutely “screamed for the Baroness”.’ The children waited for this moment and then would race down the corridor to the nursery in panicky fits of hysterics.

There is a picture of Emmy taken in the salon soon after she married Viktor. She must be pregnant with Elisabeth already, but not showing. She is dressed like Marie Antoinette in a cropped velvet jacket over a long white skirt, a play between severity and nonchalance. Her ringlets conform to what is au courant in the spring of 1900: ‘coiffure is less stiff than it was formerly; fringes are prohibited. The hair is first crimped into large waves, then combed back and twisted into a moderately high coil…locks are allowed to escape onto the forehead, left in their natural ringed form,’ writes a journalist. Emmy has a black hat with feathers. One hand rests on a French marble-topped chest of drawers and the other holds a cane. She must be just down from the dressing-room and off to another ball. She looks at me confidently, aware of how gorgeous she is.

Emmy has her admirers – many admirers, according to my great-uncle Iggie – and dressing for others is as much a pleasure as undressing. From the start of her marriage she has lovers, too.

This is not unusual in Vienna. It is slightly different from Paris. This is a city of chambres séparées at restaurants, where you can eat and seduce as in Schnitzler’s Reigen or La Ronde: ‘A private room in the restaurant “Zum Riedhof”. Subdued comfortable elegance. The gas fire is burning. On the table the remains of a meal – cream pastries, fruit, cheese etc. Hungarian white wine. The HUSBAND is smoking a Havana cigar, leaning back in one corner of the sofa. The SWEET YOUNG THING is sitting in an armchair beside him, spooning down whipped cream from a pastry with evident pleasure…’ In Vienna at the turn of the century there is the cult of the süsse Mädel, ‘simple girls who lived for flirtation with young men from good homes’. There is endless flirtation. Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier with its text by Hofmannsthal – in which changing costumes, changing lovers and changing hats are all held in suspended amusement – is new in 1911 and is wildly popular. Schnitzler has problems, he confides in his journal of his sexual congresses, in keeping up with the demands of his two mistresses.

Emmy dressed as Marie Antoinette in the salon of the Palais Ephrussi, 1900

Sex is inescapable in Vienna. Prostitutes crowd the pavements. They advertise on the back page of the Neue Freie Presse. Everything and everyone is catered for. Karl Kraus quotes them in his journal Die Fackel: ‘Travelling Companion Sought, young, congenial, Christian, independent. Replies to “Invert 69” Poste Restante Habsburgergasse’. Sex is argued over by Freud. In Otto Weininger’s Sex and Character, the cult book of 1903, women are, by nature, amoral and in need of direction. Sex is golden in Klimt’s Judith, Danaë, The Kiss, dangerous in Schiele’s tumbled bodies.

To be a modern woman in Vienna, to be comme il faut, it is understood that your domestic life has a little latitude. Some of Emmy’s aunts and cousins have marriages of convenience: her aunt Anny, for instance. Everyone knows that Hans Count Wiltschek is the natural father of her cousins, the twin brothers Herbert and Witold Schey von Koromla. Count Wiltschek is handsome and extremely glamorous: an explorer, the funder of Antarctic expeditions. A close friend of the late Crown Prince Rudolf, he has had islands named after him.

I’ve delayed my return to London – I’m finally on the track of Ignace’s will and want to see how he divided his fortune. The Adler Society, the genealogical society of Vienna, is only open to members and their guests on Wednesday evenings after six o’clock. The society offices are through a grand hall on the second floor of a house just down from Freud’s apartment. I duck through a lowish door and into a long corridor hung with portraits of Vienna’s mayors. Bookcases with box-files of deaths and obituaries to the left, aristocrats, runs of Debrett’s and the Almanach de Gotha to the right. Everything else and everyone else, straight on. At last I see people at work on their projects, carrying files, copying ledgers. I’m not sure what genealogical societies are usually like, but this one has completely unexpected roars of laughter and scholars calling out across the floor, requesting help in deciphering difficult handwriting.

I ask very delicately about the friendships of my great-grandmother Emmy von Ephrussi, née Schey von Koromla, circa 1900. There is much collegiate joshing. Emmy’s friendships of a hundred years ago are no secret, all her former lovers are known: someone mentions a cavalry officer, another a Hungarian roué, a prince. Was it Ephrussi who kept identical clothes in two different households so that she could start her day either with her husband or her lover? The gossip is still so alive: the Viennese seem to have no secrets at all. It makes me feel painfully English.

I think of Viktor, son of one sexually insatiable man, brother of another, and I see him opening a brown parcel of books from his dealer in Berlin with a silver paper knife at his library table. I see him reaching into his waistcoat pocket for the thin matches he keeps there for lighting his cigars. I see the ebb and flow of energy through the house, like water running into pools and out again. What I cannot see is Viktor in Emmy’s dressing-room looking down into the vitrine, unlocking it and picking out a netsuke. I’m not sure that he is even a man who would sit and talk to Emmy as she got dressed, with Anna fussing around her. I’m not sure what they really talk about at all. Cicero? Hats?

I see him moving his hand across his face as he readjusts himself before he goes every morning to his office. Viktor goes out onto the Ring, turns right, first right into the Schottengasse, first left and he is there. He has begun to take his valet Franz with him. Franz sits at a desk in the outer office, so that Viktor can read undisturbed inside. Thank God for clerks who can tabulate all those banking columns correctly, as Viktor makes notes on history in his beautiful slanting handwriting. He is a middle-aged Jewish man, in love with his young and beautiful wife.

There is no gossip about Viktor in the Adler.

I think of Emmy at eighteen, newly installed with her vitrine of ivories in the great glassed-in house on the corner of the Ring; I remember Walter Benjamin’s description of a woman in a nineteenth-century interior. ‘It encased her so deeply in the dwelling’s interior,’ he wrote, ‘that one might be reminded of a compass case where the instrument with all its accessories lies embedded in deep, usually violet, folds of velvet.’