18. ONCE UPON A TIME

The children in the Palais Ephrussi have nurses and nannies. The nurses are Viennese and kind, and the nannies are English. Because the nannies are English, their breakfast is English and there is always porridge and toast. There is a large lunch with pudding, and then there is afternoon tea, with bread and butter and jam and small cakes, and after that is supper, with milk and stewed fruit ‘to keep them regular’.

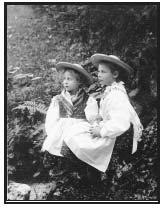

On special days the children are required to be part of Emmy’s at-homes. Elisabeth and Gisela are dressed in starched muslin dresses with sashes, while poor Iggie, who is on the plump side, has to wear a black velvet Little Lord Fauntleroy suit with an Irish lace collar. Gisela has big blue eyes. She is a particular pet of the visiting ladies, and Charles’s little Renoir gypsy when they visit the Chalet Ephrussi, so pretty that Emmy (tactless) has her portrait done in red chalk, and Baron Albert Rothschild, an amateur photographer, asks for her to be brought to his studio to be photographed. The children are driven in the carriage for a daily walk with the English nannies in the Prater, where the air is less dusty than on the Ringstrasse. A footman comes too, walking behind in a fawn greatcoat and wearing a top hat with an Ephrussi badge stuck into it.

There are two set times when the children see their mother: dressing for dinner and Sunday mornings. Half-past ten on a Sunday morning marks the moment when the English nanny and governess leave for morning service at the English church and Mama visits the nursery. In her brief memoir, Elisabeth described ‘Those two divine Sunday morning hours…She had made haste that morning with her toilette and was dressed very simply in a black skirt, down to the ground of course, and a green shirt-waist with a high stiff white collar and white cuffs, her hair beautifully piled up on top of her head. She was lovely and she smelt divinely…’

Together, they would take down the heavy picture books with their rich maroon covers: Edmund Dulac’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, Sleeping Beauty and, best of all, Beauty and the Beast with its figures of horror. Each Christmas brought the new Fairy Book of Andrew Lang, ordered from London by the children’s English grandmother: Grey, Violet, Crimson, Brown, Orange, Olive and Rose. A book could last a year. Each child would choose a favourite story: ‘The White Wolf’, ‘The Queen of the Flowery Isles’, ‘The Boy Who Found Fear at Last’, ‘What Came of Picking Flowers’, ‘The Limping Fox’, ‘The Street Musician’.

Gisela and Elisabeth, 1906

Read aloud, a story from the Fairy Books is less than half an hour long. Each story starts with ‘Once upon a time’. Some stories have a cottage on the edge of the forest, like the birch and pine forests at Kövecses. Some of the stories include the white wolf, like the one shot by the gamekeeper near the house, and shown to the children and their cousins on an early autumn morning in the stable yard. Or the bronze wolf’s head on the door of the Palais Schey, whose muzzle gets rubbed every time they pass it.

There are strange meetings in these stories, encounters with the bird-charmer with a flock of finches on his hat and arms – like the one you see standing in a circle of children on the Ringstrasse outside the gates of the Volksgarten. Or with pedlars. Like the Schnorrer with his basket of buttons and pencils and postcards hanging from his black coat, who stands by the gates out onto the Franzensring and to whom they have been told by their father they must be polite.

Lots of stories include the Princess getting dressed in her gown and tiara to go to the ball, like Mama. Lots of stories have a magic palace in them with a ballroom, like the room downstairs that you see lit with candles at Christmas. All the stories finish with ‘The End’ and a kiss from Mama, and then no more stories for another whole week. Emmy was a wonderful story-teller, said Iggie.

The other time that the children regularly see her is when she is dressing to go out and they are allowed into her dressing-room.

Emmy would change out of her day-clothes, in which she had received or visited friends, into her clothes for dinner at home or, the opera, or a party or, best of all, a ball. Dresses would be laid out over the chaise longue and there would be a lengthy discussion with the expert Anna over which one to wear. The eyes of my great-uncle Iggie used to fire as he described her animation. If Viktor had Ovid and Tacitus – and his Leda – at one end of the corridor, then at the other end Emmy could describe dresses that her mother had worn season by season, how lengths were changing, how the weight and fall of a gown altered the way you moved, the differences between a muslin, gauze or tulle scarf across your shoulders in the evening. She knows about Paris fashion and what is à la mode in Vienna, and how to play the two. She is especially good on hats: a velvet hat with a huge ribbon on it to meet the Emperor; a fur toque with an ostrich feather, worn with a column dress trimmed in black fur; the best hat in the line of Jewish ladies at a charity do in a small ballroom somewhere. Something very wide indeed with a hydrangea on its brim. From Kövecses, Emmy sends to her mother a postcard of herself wearing a dark Makart hat: ‘Tascha shot a buck today. How is your cold? Do you like my newest affected pictures?’

Dressing is the hour when Anna brushes her hair and laces corsets, fastens innumerable hooks and eyes, fetches variant gloves and shawls and hats, when Emmy chooses her jewellery and stands in front of the three great panels of mirror.

And this is when the children are allowed to play with the netsuke. The key is turned in the black lacquer cabinet and the door is opened.