Overview

The purpose of this chapter is to

explore lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) elders with

histories of incarceration. This chapter reviews the history of

research and practice in this area, major issues and relevant

policies, new research that is critical to understanding LGBT elder

in the criminal justice system, and the role of interdisciplinary

practice in improving service delivery for this population. Due to

the paucity of the literature available on this population, this

chapter provides new data from a qualitative study of ten formerly

incarcerated LGBT elders’ experiences prior to, during, and after

release from prison. Consistent with intersectionality theory, a

core theme of self and the social mirror emerged from the data that

represented LGBT elders’ ongoing coming out process of unearthing

their ‘true selves’ despite managing multiple intersectional

stigmatized identities, such as being LGBT, elderly, HIV positive,

formerly incarcerated, and a racial/ethnic minority. These

exploratory findings further our awareness of an overlooked

population of LGBT elders involved in the criminal justice system.

The implications for interprofessional and interdisciplinary policy

and practice that incorporate suggestions from the formerly

incarcerated suggestions for systemic reform are discussed.

Learning Objectives

By the end of the chapter, the reader

should be able to:

1.

Articulate some of the common

experiences of LGBT elders involved in the criminal justice system,

especially related to prison and community reintegration.

2.

Identify intersectional social

locations or identities of LGBT elders with criminal justice

histories.

3.

Describe the sources of trauma, stress,

and oppression and resilience among this population.

4.

Identify service and justice gaps on

how to improve the interprofessional response to LGBT elders

involved in the criminal justice system.

Introduction

The steady growth of a graying of the

global prison population is perhaps most challenging in the United

States (USA). The USA has the highest rate of incarceration in the

world (Walmsley 2013). As of 2013,

prisoner population rates per 100,000 were 716 in the USA compared

to 475 for Russia, 148 in the UK, 121 in China, and 118 in Canada

(Walmsley 2013). In 2012, one of

every 35 adult residents in the USA (2.9 %) was in jail,

prison, or on parole or probation (Glaze and Herberman

2012). Of the estimated 1.5 million

persons in the state and federal prison in the USA in 2013,

18 % (n = 270,000) are aged 50 and

older (Carson 2014).

A profile of older adults in USA

prisons portrays a diverse population that disproportionally

affects vulnerable populations based on characteristics such as

age, race/ethnicity, gender, and disability (Maschi et al.

2014). For example, in the US

prison population aged 50 and older, the vast majority are men

(96 %) compared to women (4 %) and are disproportionately

racial ethnic groups (black = 45 %,

Latino = 11 %, 10 % = other) compared

to whites (43 %; Guerino et al. 2011). Health status varies; some individuals

have functional capacity, while others suffer from disabilities or

serious, chronic, and terminal illnesses such as HIV/AIDS, cancer,

and dementia or mental health (e.g., depression, anxiety,

psychosis) and substance abuse problems (36 %; BJS

2006; Maschi et al. 2012a, b). The

majority report a history of victimization, grief and loss, and

chronic stress prior to and during prison and varying levels of

coping and social support (Maschi et al. 2012c, 2013b).

Despite this knowledge, there is a

dearth of research that examines the experiences of LGBT elders

involved in the criminal justice system. The pathways to prison for

older adults in prison may include one or more cumulative

inequalities (Maschi and Aday 2014), such as social disadvantage based on age,

race, education, socioeconomic status, gender, disability, legal or

immigration status, and sexual minority status (Maschi et al.

2014). These accumulated

inequalities can influence access to health and social services,

economic resources, and justice across the life course. This is

uniquely applicable because of their criminal justice history,

which is largely not addressed in intersectionality theory.

History of Research and Practice Pertinent to This Topic

Civil and human rights advocacy groups

that respect an inherent dignity of older and LGBT persons are

gaining momentum. The United Nations has designated a number of

special needs populations that are subject to special protections.

These special populations include lesbian, gay, bisexual, and

transgender (LGBT) prisoners and older prisoners in addition to

prisoners with mental health care needs, disabilities, racial and

ethnic minorities, women, foreign-born nationals, and prisoners

with terminal illness or under a death sentence (United Nations

Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC] 2009). Given that many people in prison have

complex needs, the likelihood is quite high that incarcerated

people who are LGBT would also be represented in one or more of

these vulnerable care populations.

Yet, the little information available

on LGBT people in prison is mostly based on younger as opposed to

older persons. In a US Department of Justice report on sexual

victimization in jails and prisons (Beck et al. 2013), inmates identifying their sexual

orientation as gay, lesbian, and bisexual were among those with the

highest rates: 12.2 % of prisoners and 8.5 % of jail

inmates reported sexual victimization from other inmates, and

5.4 % of prisoners and 4.3 % of jail inmates reported

victimization by staff. It is of concern that inmates with mental

health needs who were identified as non-heterosexual reported the

highest rates of inmate-on-inmate sexual victimization (i.e.,

14.7 % of jail inmates and 21 % of prison inmates). In a

study of violence in California prisons , transgender women in

men’s prisons were 13 times as likely to experience sexual violence

than were other prisoners (Jenness et al. 2007). Incarcerated LGBT persons also have

health care concerns that include sexually transmitted diseases

(STDs), including HIV/AIDS, and mental health and substance use

disorders. The health care of transgender prisoners is often an

administrative issue versus a health care issue due to

institutional policies preventing hormone and/or transition-related

care (Marksamer and Tobin 2014).

LGBT persons are also at high risk of

family rejection, homelessness, and unemployment due to bias and

discrimination based on their LGBT status. LGBT persons may reject

(lack) access to prison-based rehabilitative services for fear of

being assaulted by other incarcerated persons or correctional

staff. Incarcerated LGBT people have special considerations pre-

and post-release because they may not have ready access to family

supports or therapeutic services, especially if they have

experienced trauma during their incarceration (UNODC 2009). These scant findings suggest that LGBT

elders released from prison, especially those with complex issues,

such as being HIV positive with comorbid health and mental health

issues, may also experience the collateral consequences of

incarceration, ageism, and homophobia. The complexity of their

situation may create additional barriers for (LGBT) them to gain

access to culturally responsive healthcare, housing, employment,

and social welfare benefits (Maschi et al. 2012c). Additional research is needed to further

our knowledge of public health issues, especially as it relates to

diverse elders who are at a heightened risk of health and justice

disparities. Therefore, in this next section, we present new

findings on the experiences of LGBT elders before, during, and

after prison and service providers that were used to identify

research, practice, and policy gaps.

Discussion Box 12.1

The current literature finds that

there are scant findings that suggest that LGBT elders released

from prison, especially those with complex issues, such as being

HIV positive with comorbid health and mental health issues, may

experience the collateral consequences of incarceration, ageism,

and homophobia.

The complexity of their situation may

create additional barriers for them to gain access to culturally

responsive healthcare, housing, employment, and social welfare

benefits. In an essay form or in a small group discussion, please

answer the following questions:

1.

What do you think accounts for the

lack of research or information on LGBT elder involved in the

criminal justice system compared to other LGBT issues ?

2.

Based on existing cross-disciplinary

theories or your own thoughts, what do you think accounts for the

interpersonal social and structural barriers for LGBT to access

services and justice?

3.

How do you think access to services or

justice can be achieved for LGBT elder in the criminal justice

system?

Major Issues of Chapter Topic and the Relevant Policies

Due to the lack of research on LGBT

elders involved in the criminal justice system, the following

two-phase qualitative study was conducted to explore the

experiences of formerly incarcerated LGBT elders before, during,

and after prison. Research in this area has important implications

for developing an intersectional LGBT aging sensitive and social

and public care approach to prevention and intervention that target

diverse elders’ pathways to prison and community reintegration ,

including care transitions. The number of diverse elders behind

bars has increased more than 1300 % since the early 1980s and

is projected to increase four times by 2030 (Human Rights Watch

[HRW] 2012). Correctional service

providers are ill-prepared to address the specialized long-term

health and social care needs of an older special needs population

(Maschi et al. 2013a,

b). In the USA, federal and state

governments spend a combined $77 billion annually to operate

correctional facilities (ACLU 2012). A coordinated public health practice and

policy response can assist with improving access to health and

justice for an all-too-often group of minority elders (Maschi et

al. 2012c, 2014).

Research Box 12.1

-

Title of Research: LGBT Elder and the Criminal Justice System

-

Research Question: What do LGBT elders report about their experiences before, during, and after prison?

-

Methods: This qualitative study participatory translation research methods is featured in this chapter. The study was conducted in two phases. Phase one consisted of in-depth interviews with 10 LGBT elders released from prison. Phase two consisted of a photograph and film documentary project.

-

Results: Participants commonly reported experiences of discrimination and victimization. A core theme of self and the social mirror emerged from the data that represented LGBT elders’ ongoing coming out process of unearthing their ‘true selves’ despite managing multiple intersectional stigmatized identities, such as being LGBT, elderly, HIV positive, formerly incarcerated, and a racial/ethnic minority.

-

Conclusion: These exploratory findings further our awareness of an overlooked population of LGBT elders involved in the criminal justice system. The implications for interprofessional and interdisciplinary policy and practice that incorporate suggestions from the formerly incarcerated suggestions for systemic reform are discussed.

-

Discussion Questions (essay or small or large group discussion)1.What are your thoughts on participatory action research in which the faces and personal background of participants are known?2.How does this differs from traditional research methods in which anonymity or confidentiality is a core research ethic?3.If you were to design a study of LGBT elders in the criminal justice system, what would be the purpose and rationale of your study, your research question, and the methods used?

Methods

Research Design

Phase One: The authors used a research

design that they refer to as ‘participatory translational

research,’ which was conducted in two phases. In phase one, LGBT

elder adults aged 50 and older released from prison within the past

five years were recruited to participate in the project. The

research team posted an announcement and invitation that described

the study on the bulletin boards of regional correctional community

service providers and parole offices. Handouts were available

directly below the posted study announcement and an invitation for

potential participants to review and voluntarily respond to the

research team by phone or mail. Snowball sampling methods also were

used to recruit participants in Brooklyn, New York, which had a

high concentration of LGBT persons in the community and an LGBT

psychosocial program.

Ten participants who responded to the

announcement and invitation met with the members of the research

team to find out more about the study and provided their informed

consent to participate in the study. First, two ninety-minute focus

groups were conducted with formerly incarcerated LGBT elders, with

five participants persons per group. The focus group interview

schedule consisted of ten open-ended questions that asked attendees

about their experiences before, during, and after prison. One week

later, each participated in a one-on-one 90 minute,

semi-structured in-depth interview. All interviews were held in a

private room at the principal investigator’s office building that

was at a central location and easily accessible by public

transportation. All interviews were administered by the principal

investigators and two trained MSW students with personal histories

of incarceration. The one-on-one interview schedule was divided

into three parts that asked participants detailed questions about

their experiences of self and community before, during, and after

prison. The interviews were recorded using a digital audio recorder

and were transcribed verbatim. Participants were offered a

thirty-dollar gift card for their participation for each interview

completed.

The qualitative data from service

providers and formerly incarcerated older adults were analyzed

using Tutty et al.’s (1996)

qualitative data analysis coding scheme. The first step involved

identifying ‘meaning units’ (similar to in vivo codes) from the

data, that is, the first-level codes were assigned to the data to

accurately reflect the writer’s exact words (e.g., true self,

homo-thug). Next, second-level coding and first-level ‘meaning

units’ were sorted and placed in their respective categories (e.g.,

‘going in’ or ‘coming out’ of prison). A constant comparative

strategy was used to ensure that meaning unit codes were classified

by similarities and differences and carefully analyzed for

relationships, themes, and patterns. The categories were examined

for meaning and interpretation. A conceptually clustered diagram

was constructed to detect patterns and themes and develop a process

model (Miles and Huberman 1994).

Phase

Two: Phase two was a participatory action documentary

project. A collaborative partnership was formed by the research

team and formerly incarcerated LGBT volunteers to design and

implement the project to increase public awareness and combat

societal stigma. The LGBT elders were especially concerned about

the invisibility and lack of culturally responsive services for

incarcerated and formerly incarcerated LGBT elders. Ron Levine, a

social documentary photographer and creator of the ‘Prisoners of

Age’ project, was recruited to be a part of the team. The

‘Prisoners of Age’ project has been an ongoing is a series of

photographs and interviews with elderly inmates and corrections

personnel conducted in prisons both in the USA and Canada since

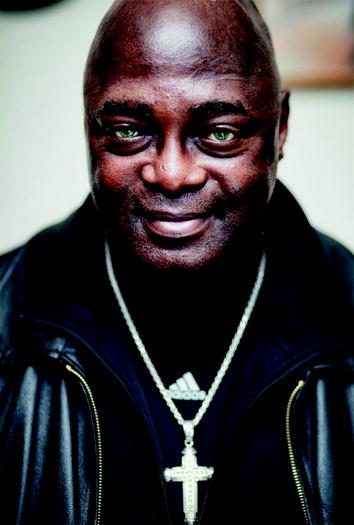

1996. A photograph of an elder transgender person in prison can be

found in the chapter appendix (See Image 12.1). The exhibit is

designed to play a role in stimulating social and institutional

change by addressing the issues of social justice and human dignity

through images and interviews. The photograph exhibits have been

shown internationally.

Image 12.1

Prisoners of age photograph of Christine

White. Photo © Ron Levine.

Reprinted with permission

For the first round of recruitment,

three formerly incarcerated LGBT elders agreed to participate in a

short documentary project. The participants signed a release form

for their photographs and interview excerpts to be used for the

documentary project. The 90-min interviews were shot with a Canon

5D mark II camera and 50- and 85-mm lenses. Sound was direct to

film using a RODE shotgun microphone attached to the flash plate.

During the shooting, the filmmaker asked the participants to

describe their past and current experiences, and future goals. The

footage was edited to be a 5-min documentary short.

Self and the Social Mirror

Phase One Qualitative Results

An overarching theme ‘self and the

social mirror,’ emerged from data about that described their

lifelong process of managing the ‘visible’ and ‘invisible’ prisons

of oppression, social stigma, and criminal justice involvement.

Self in the social mirror was defined as a dynamic personal,

interpersonal, and historical process that involved the mutual

reflection (or deflection) of participants’ diverse selves with

family and friends and society. Many participants described a

lifelong process of integrating aspects of their social identities

or location that were commonly subject to bias, discrimination, and

violence. Many participants viewed themselves by one or more of

following identities (or social location): being a racial/ethnic

minority, older, HIV positive, LGBT, formerly incarcerated with a

mental health and/or substance diagnosis, occupational status and

income, and geographic location. Participants shared their views on

how they multiple social identities or locations, such as

race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, or their serious mental health

status. When asked to ‘tell me about yourself,’ participants

commonly identified themselves as LGBT and then added one or more

other aspects of themselves.

I am an African-American female, 55, um, what else do I want to say. Um, I’m presently unemployed. I was incarcerated for like six years on a drug charge. Um, and um, it wasn’t easy, but I’m okay now.

I’m a lesbian um, presently. I’m not in any committed relationship or anything like that and um, well. I’m presently doing, I’m focusing on my recovery you know and just trying to stay in the community.

Um, Latino and I’m LGBT, GQ. And I did sixteen years in prison for manslaughter and I learned a lot in prison. It took me time to learn about myself. I was a closet gay person, didn’t want nobody to know who I was, and I’m learning how to live life, and I’m in a relationship for six years, and I love myself today.

I did ten years, six months in prison. I am a gay male. I’m in a committed relationship for the last six years. Um, I’m presently working in the mental health field in a psychosocial club and advocacy program for LGBT members. Um, helping to be a liaison between their therapist and the support they receive. Um, one of the things that um, I’m trying to do after coming out of prison for so long is to establish a working relationship um, and being a productive person.

Building ‘Immunity’ to Social Stigma

Participants commonly reported that

they faced challenges to developing a strong sense of self and a

relationship to their families and communities. Social stigma was

described as a communicable disease in which some participants

developed immunity to external oppressive attitudes and practices.

Some feedbacks seemed to accurately mirror and support the

expression of their ‘true selves.’ Other feedback was potentially

obstructive to that expression. Many participants described a

multi-dimensional ‘coming out’ and self-acceptance process, which

included being LGBT. Social and historical circumstances influenced

how they negotiated this identity before, during, and after prison.

One 55-year-old formerly incarcerated woman shared the following:

Well, no, well I don’t know if it’s me, but I personally don’t care how a person feels about me. You understand what I’m saying. My attitude is that if you don’t like what I represent, don’t, don’t, you know, don’t say nothing to me. I can keep it moving and that’s it and that’s all so nobody, I never got approached on that but I’m quite sure you know, it would whatever but I never personally got approached about it so as far as me being LGBT and being incarcerated, it wasn’t a problem for me.

Another participant described how he

was always prepared to protect himself and vocalize his rights,

especially to culturally incompetent community professionals and

service providers.

You have to put your guards up in every way possible that’s going to help you to get ahead, being gay for me, HIV positive, black, you know, a whole lot of stuff, you know. So, you have to set up certain things that are going to defend you along the way. Otherwise you’re going to get swallowed up. I’m not just accepting anything but capable of advocating for myself, especially when I need affirming program services. If you can’t advocate, that becomes a stumbling block.

Many participants shared their earlier

life experiences in which mirroring from families, peers, and

communities varied concerning how they chose to share one or more

of their ‘intersectional’ aspects of self. It is important to

understand that identity is comprised of many different facets,

including, but not limited to, our biological sex, gender identity

and expression, sexual identity, class, race, and age. We make

choices throughout our lives to express or hide these aspects of

ourselves. Ward (2008) has shown

that race, class, gender, and sexuality are important in

structuring our identity and that examining our sexuality is

integral to viewing the intersectionality of the many facets of

self. Being HIV positive, having a serious mental health illness,

or being LGBT and engaging in criminal behavior are often

selectively disclosed to families, peers, and other social circles.

Being HIV Positive: By immediate family, like my mother, father, sister, and brother, I know and they all know my HIV status. Uh, my father, I haven’t really told my status, you know, um. You know, even though I know he would love me because I’m his son and, and he would just, I mean, he wouldn’t have a choice, but I just don’t feel comfortable coming out telling him that I’m HIV positive. I brought it to my mother’s attention, and my mother, she’s like, she says, no, don’t tell him, you know, and I don’t know why, but I just keep, we’re just keeping that a secret. But everybody else knows. My brother knows. My sister knows. My aunt knows, you know.

Being Diagnosed with a Mental Illness: Growing up, my family wasn’t really cool with being mentally ill so I couldn’t be mentally ill. I was not able to go to a psychiatrist. I was not able to take medication, and I was damn sure not able to talk about how I felt or what was going on. So, I self-medicated with drugs. The voices were getting loud, drink a little bit more, smoke a little bit more.

Most of the time voluntary um, but a lot of the times involuntary because my mother had to put me there. I can’t even count. Let’s say 30 times from the age of 26 to 35. I think I went to the psych hospital, about two or three times a year for like 10 to 12 years.

Being Gay and Engaging in Violent Behavior: That they all knew my name in jail. One guard, her name was R, said yo, R’s back. I used to stay in the lock up a lot and she would ask, ‘Like are you sure you are a homo?’ The officers used to tease me like how could a homo be doing all this. Homos don’t do this.

‘Inside’ Prison

The legal system itself may have

imposed discrimination prior to actually being sentenced and

entering prison. Individuals may be exposed to the personal

feelings or biases of the police, lawyer, or judge who impacts

their treatment and sentencing. Participants described prison as a

mixed experience of self in their social mirror. All participants

acknowledged the cruelty of prison, especially for LGBT persons.

Yet, despite the conditions of confinement, participants also

acknowledged that they could use their time to gain greater insight

and clarity about themselves and take accountability for their

crimes. Many participants provided a thick description of the grave

and dangerous social conditions of confinement, especially for gay

men and transgender persons in men’s prisons compared to lesbian,

bisexual, or transgender person in a women’s prison. As

participants described below, the culture of prison was full of

systemic bias and discrimination that limited their access to

rehabilitative services and basic safety and protections.

It was like this in jail, if you are male and gay so you should like it, you know. So um, it was really hard to go through that and try to deal with the day, you know, and days were long, you know. You were up at 7, you know, and even your time locked in your cell wasn’t a safe time, because if they wanted you, they could tell a CO to crack your cell and they would run in on you. You know it was really frightening. It was hard to get yourself mentally ready for the morning because you never knew what was going to happen that day, and that’s a real terrible feeling like, what’s going to happen to me today. Every day was like, I got to keep up. I got to keep up. I got to look left. I got to look right because people were just being abused all throughout my stay, and the LGBT was just assaulted so many times on a regular basis. Everyone got it, but the LGBT men, they just you know, they were washing and underwears and anything their parents sent them or friends sent them, they would take them you know and they would make them cook for them and wash their pots. It was just frightening.

The CO’s didn’t care about anything. They watched gay people get raped. They would walk the tier and see you being raped in your cell or being beaten in your cell, and they would keep on walking, you know. Um, they would see you get beat and raped in the shower room, and they wouldn’t say anything, and when you needed help to cry out to the CO, it was like crying out to air, you know, because they weren’t going to do anything.

‘Gay’ Coping in Prison

When it came to negotiating their

sexual and gender identity, participants described choosing among

one of three ‘gay’ coping strategies: fight (i.e., defending the

right to be openly gay), flight (i.e., complete distancing from

one’s LGBT identity in prison often out of fear of safety), or

keeping it out of ‘sight’ (i.e., selectively disclosing one’s LGBT

identity). The choice to use one of these coping strategies

influenced their level of access to health, mental health, and

rehabilitative services, including education.

-

Flight: Well, nobody, nobody, nobody knew I was gay. Only a few guys I let know, but other people, I just say no, I’m not gay. I’m old man. Having sex in prison is not acceptable. No, if you get caught, they send a letter to your house, or they tell your family over the phone, you know. You go to the box. Some, some officer, some CO, some correctional officer, they’ll let you be with your lover in, in the other cell. Some people you just paid the officer off, be kind of cigarette or with drugs.

-

Out of Sight: Um, it was a hard life in jail because you had to walk around like on pins on needles. It wasn’t that good especially if you was gay or bisexual. I wasn’t the type of person to walk around and? Advertise, and only a few people knew. I wasn’t the type of person that wanted to be taken advantage of and being raped, so I had to learn how to defend myself in jail. I went through a lot of, lot of tough times. It wasn’t that easy for me. But I’m easy to get along with so I guess my uh, word of mouth got me by. I was able to get along with everybody. I wasn’t selfish. You know, try to stick with this one, that one. I stuck with who I needed to stick with to get by in jail if it helped me that way.

-

Fight: How did I cope with being gay in prison? I did when in Rome, do as Romans. When in Rome, do as Romans. I was in jail I did what jail people do. So I hung out with a crew that were crazy. I was hearing voices, I was crazy so we did the same thing and the only reason they accepted me is because I was just as dangerous as they were. I was always gay all my life so when I got in jail um, I never went into you know, segregation or into the gay quarters. I always went into general population and um, I made myself deal with what was going on and I became one of the people that were there. Fighting was just, I don’t know if it was more because I was LGBT or because it’s just what you do in jail, but I know that I went through a lot being an openly gay person in jail because the attacks and things that happen to uh, that I had observed happen to gay people were really frightening, and I just made it a way of my dealing in jail that it wouldn’t happen to me so I became a really, really wild person um, they have a name for gays like me in jail and it’s homo thug. I became like one of the fearless gay people in jail um, I just didn’t want to be raped.

‘Coming Out’ of Prison

Return to Community. Participants’

perceptions of self in the social mirror continued to evolve after

they ‘came out’ of prison. Many participants, especially those with

long-term prison sentences, described feeling fear if correctional

or community program staff did not help prepare them for impending

release. Preparation for reentry is essential for individuals to

reintegrate into the community successfully. Aside from challenges

of returning to the community with the stigma of having served

time, there may be essential skills that have to be mastered for

them to manage in the community, such as budgeting, meal

preparation, and accessing essential social services for medical

and mental health needs. Some of those returning to the community

have been ‘in the system’ for so long that they have lost their

ability to care for themselves independently and have become

‘institutionalized.’ Since entering prison, they have been told

when to get up; had their meals prepared; and were provided with

shelter, medical care, and direction for most of their daily

activities.

Isolation in Community. Entering the

community and relearning self care, managing the demands of

maintaining housing in terms of cleaning, shopping, and cooking,

and interacting with others in a socially acceptable way are

critical to remain outside of incarceration. For some, life outside

of prison is isolating, and they have very little left of family,

friends or social supports.

There was nothing for me out there, which made coming home a little more frightening, and for the LGBT it’s like that. Why leave prison, I’m getting three hots and a cot. I don’t have to fight for the food, you know. Some of us don’t want to come out, and it was a feel like, what am I going to do at this late age. I think I came out at, I’ve been out almost four years. I came out at 46 years old. I didn’t know what, what am I going to do, where am I going. I knew I didn’t want to go to a program and stay at a program you know, like programs and, you know, it pushes us out to the street.

Other participants reported adopting a positive attitude of success on their road to recovery despite anticipated challenges posed by the culturally destructive social mirroring and practices. One participant described how he prepared himself psychologically, emotionally, and spiritually to triumph over challenges, especially bias and discrimination, he believed he would face being older and gay and serving a 15 year sentence for attempted murders.

Everything’s been beautiful. I just don’t allow it to be any other way. Every day I wake up, I’m so appreciative to not be behind bars. Nothing that comes up, no weather conditions or anything, and my partner says, baby, you are up at 6 o’clock no matter what goes on. I praise God in the morning, and just like yeah, it’s time to go. I think I was given a second chance. My second chance. A second chance at life, and I just don’t want to mess it up. I can’t say there has been any difficulties. There’s been situations, and I just take them in stride. Because all of it is a work in progress. I went into mainstream, I didn’t wait for the housing because I was in a relationship that I wanted to do, and they had informed me that any of the housing that I got would not allow me and my partner to merge. And as I said, I’m 50. I’m not going to be living alone. And going to see my partner who lives in the Bronx and I’m over here, you know. They are not recognizing LGBT relationships. That’s an issue.

Access to Services. Some participants

talked about the advantages of having a stigmatized label that

comes with legal protections and services, which include having an

HIV positive status or diagnosed with a serious mental illness.

And you were talking about like supports coming out of prison, you know, being LGBT and be labeled HIV, you get a lot of stigma but you get a lot of support on your transition out. Otherwise, we don’t get anything. Um, we don’t even get the assistance to try to get housing. You have to find a social worker and tell her look, can you start the paperwork, because I heard it could be done from here, and then she be like, well I don’t know about that. Will you look it up while the paperwork’s here, you know, and be on them like I know something that you could do for me. But if you don’t, you know what I’m saying, but for us coming out and you’re not HIV positive, then you don’t find something for yourself, you’re going to the street.

Referral for services to assist with

mental health, health, housing vocational and/or educational

services is very important in community reentry . Having the dual

stigma of being incarcerated, having a medical or psychiatric

diagnosis, and needing social and financial supports upon release

are critical for most individuals released from a forensic setting.

Participants shared how reentry or housing supports and services

that were not LGBT and aging friendly influenced their ability to

express to be open about themselves and receive adequate peer,

family, professional, and/or community support.

The housing that I was in was lovely, but I was with people that weren’t LG affirming and weren’t as mentally equipped as I was so I was having to live in. Sometime in the environment that wasn’t safe for me, and sometime wasn’t healthy for me.

Well, when I came out um, there was a reentry program, I worked with them very well. They helped me out in a lot of ways. I went to school with them um, I went through their training program, and I even got jobs through them so they helped me out a long way until I was able to get on my feet again at a reentry program. But they did not have LGBT and aging services. That right there if it was it was kept in the closet. I didn’t see too many open gay people there you know saying just straight thugs, you know, from the street and stuff like that from locked up, but it wasn’t really, if it was it was under the cover, it was in the closet, but it wasn’t brought out in the open like that, it was just mostly thugs.

Housing. Another important

consideration in housing is the restrictions placed on certain

types of offenders. There may be restrictions on where they can

reside, such as not within a certain distance of a school, park, or

public housing. This may make returning to family or their prior

residence impossible. Being relocated after serving time to an

unfamiliar, or unsafe area, has obvious implications. There may be

curfews or required appearances that make finding employment, or

attending a program, difficult. One participant described the

drawbacks for not having services that integrate LGBT, aging, and

criminal justice services:

I don’t think like, when you get out if you are LGBT they have a few things but you age out at 24 and those are the couple of things that they have right now but for our age 40 and 50 there are no specific services. They don’t even have housing where they can sufficiently put you. Yeah, they got one LGBT elder program now, but I don’t seem them helping people coming out of jail. That’s support for, you know, people on the street for LGBT but coming out for senior citizens like if you are LGBT in jail and you’re getting out, they going are going to push you over there at the LGBT youth center. But for anybody over that age, there’s nothing. And then when you get 40, it’s like you’re on your own, we’re letting you go, but where you going is on you. They don’t have no kind of referrals. They have no kind of support so everything is really on you to be strong and look for, but people get discouraged really quickly because it’s like next to no that you are going to find services. And the services that they have, they may not be able to accept you because they are at their quota with LGBT but 40–50+. We have to depend on our family and most of us don’t have that.

Rainbow Heights: A Pocket of Hope. All

of the participants were members of the Rainbow Heights Club, which

is an LGBT affirmative psychosocial service provider in Brooklyn,

New York. Their staff has been trained to work with LGBT-identified

clients with multiple problems related to their mental health, past

history, and skill set. The participants described their

experiences there:

There’s not a lot for the LGBT. I thank God for Rainbow Heights and being a person that can provide service for people that have nowhere to go to be themselves, to be safe, to eat a meal. To get support and referral to a lot of things that they may need in their life but we are only one and we’re the only one in the whole United States, Rainbow Club so more.

Phase Two Results

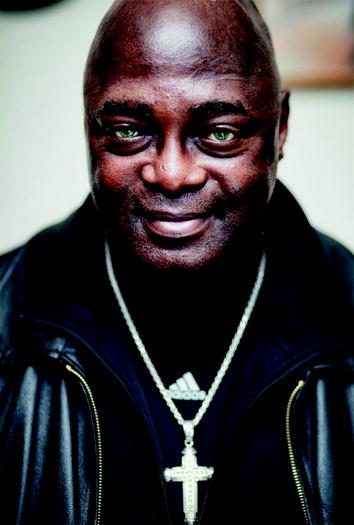

For phase two, the first filming took

place in Bedford-Stuyvesant in April 2014. The three volunteers,

Randy, Mark, and Dwon, identified themselves as formerly

incarcerated LGBT elders who had spent most of their recent prison

sentences at Sing-Sing Correctional Facilitate in upstate New York.

Recently, Randy and Mark were legally married under New York State

law. The photograph and interview session lasted about an hour and

a half. An excerpt of the interview transcript can be found in

Table 12.1 in the chapter appendix, and photographs

can be found in Images 12.2 and 12.3 in the appendix. The final short

documentary was edited down to 5 minutes by Mr. Levine. In the

interviews, Randy spoke about his life before prison and his life

within the penitentiary, emphasizing his experiences as a gay man

within the prison system. He talked generally about survival in

prison and specifically about his survival techniques as a member

of the LGBT community in prison, his coping skills, and his own

personal experiences. Mark appeared to be shy and spoke minimally

about his experiences. Dwon discussed his experiences living his

life on the ‘down low,’ and about hiding his homosexual identity by

dating both men and women in the past. He emphasized his wish to

find a life mate like Randy and Mark have done. The five-minute

short documentary can be found on the Prisoners of Age Facebook

page at the following link: https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?v=10204217999038834&set=vb.1493049016&type=2&theater.

Table 12.1

Excerpt from interview transcript prisoners

of age documentary on formerly incarcerated LGBT elders

|

RE:

My name is Duwan. I’m 55-years old. I was born in Brooklyn, New

York. I was on the down low. You know, I didn’t really start coming

out into—well I came out when I was young. But, I mean, it was just

really hard for me to accept that, you know, and I went through men

and women, because I was trying to find myself, you know

|

|

RE:

I’m Randy Killings, and I’m 49. Well I was originated in Brooklyn,

and my mom had me in Jamaica and came back to New York

|

|

RE:

My name is Mark. I’m 44-years old. I was born in Manhattan. Went to

prison for a while. And now I’m here enjoying my life

|

|

IN:

So tell me, I want to hear the love story

|

|

RE:

Well, actually we met on the medication line going to medication

that one night. And one of our mutual friends had brought Mark

down. I think he had just got transferred here

|

|

RE:

Yeah, I got transferred here

|

|

RE:

He said I got somebody I want you to meet, and he told him the same

thing. And when we met I just was attracted instantly, which was

unusual for me, because I don’t usually deal with any kind of

activity in jail. But when I saw him I said you’re going to be my

husband. And he laughed. And the next day we started a

relationship

|

|

RE: I

grew up always gay, but I was so boisterous and strong with it I

didn’t get a lot of abuse or stigmas or things that most gays go

through

|

|

RE:

Everywhere I went everyone would be like, you know, that’s Randy,

he’s gay, but you all don’t mess with him. He ain’t dealing with

that, you know

|

|

RE:

We were in something called maximum prison. Maximum prison, people

who are not actually coming home for a very long time if they’re

coming home. So the mindset is like this is mine, this is how I’m

going to run it, and that’s how it was, and there was no changing

it

|

|

RE:

Because you have to get stronger in jail, you really do, because

there’s such a closed in community where if you’re not strong

enough you’ll get sucked under

|

|

RE:

Yes, you get sucked under

|

|

RE:

You’ll be devoured

|

|

RE: I

was always a good person, but the reason I was in jail this time

was because at that time I was into a lifestyle where it was a lot

of money. I hung out with a lot of guys, it was a stick up crew.

And we wore a lot of jewelry and stuff. And I smoked crack. As I

was leaving the guy tried to rob me outside of the crack house, and

we were fighting, and I punched him hard, and he fell backwards

onto the Johnny pump, and it went through his head. In the time it

took for me to be released they told me, they gave me a CRD to get

out. I immediately just laid down everything. I stopped using,

which was predominately my problem. I transferred to another side

of **, which was called the Core Program, which helped people

integrate back into society and give them an option. And I knew

that if I went back to where I was from that it would be really,

really hard for me. I signed for Project Renewal PTS Program. It

was Transition Housing for Parolees. Right there I prayed that God

would take the taste out of my mouth not to get high, because I got

clean, but it was a different feeling when I was in the free air,

you know. So I had to go to a program for a year, which I completed

very, very quickly. I graduated in like four months. And my

director said, you know, you have a gift, because I was always

helping people and connecting with them. And he said maybe you need

to think about counseling

|

|

RE: I

look at them, and I see these two how their relationship, you know,

I mean, they’re married and stuff like that, and that’s what I want

to be. Right now, you know, I’m looking. I’m hoping to find

somebody nice that, you know, I could grow old with, you know,

spend the rest of my time with

|

Image 12.2

Randy and Mark. Photo © Ron Levine. Reprinted with

permission

Image 12.3

Dwon. Photo © Ron Levine. Reprinted with

permission

Research Critical to Issues Discussed in This Chapter

This qualitative study explored the

experiences of formerly incarcerated LGBT elders. A central theme

of self and the social mirror-emerged participants described a

process in which they built a strong sense of self and pride, often

in response to bias, prejudice, discrimination, and violence due to

the nature of their multiple minority identities, which included

being LGBT, HIV positive, racial/ethnic minority, formerly

incarcerated, and being diagnosed with a serious mental illness.

Despite the many challenges, most of the participants described

resilient coping strategies that helped them navigate oppressive

attitudes and practices that were pervasive in community and

institutional settings.

These findings build upon the existing

literature on marginalized LGBT elders. Similar to Addis et al.

(2009), review of the literature on

the needs of LGBT older people, these findings also showed that

discrimination based on a LGBT sexual orientation has a major

impact on meeting their needs in health and social services. The

narratives from the current study of formerly incarcerated older

adults underscore their struggle to be recognized for their true

selves, which consisted of multiple intersectional identities and

striving for individual and collective empowerment. Many

participants expressed the strong desire to engage in the dialogue

about what are the problems and solutions for LGBT minority elders.

In recognition of this request, the recommendations for system

reform are taken directly from formerly incarcerated LGBT elders.

As shown in Table 12.2 of the chapter appendix, participants

recommended the adoption of more compassionate and affirming

practice and policy approaches, non-discrimination and special

population considerations, post-prison release access to culturally

responsive safe and affordable housing, services, family and peer

supports, and leadership and justice and advocacy opportunities.

These recommendations have implications for interprofessional and

interdisciplinary service delivery and approaches.

Table 12.2

Formerly incarcerated LGBT elders

recommendations for system reform

|

1. Adoption

of more compassionate and affirming practice and policy

approaches

We need to reform the whole criminal

justice process. Like the intake process in prison. I don’t know if

they do it like that as some type of scare tactic or what. The way

they the intake is like they can give you like a very negative

outlook on, on, on, on life in prison. And if you’re not an

open-minded person, you can go through your whole sentence being in

fear. I think they need to be a little bit more compassionate on

intake because if you’re full of fear, you’re not open to anything,

you know. So you go in jail or prison and you think you got to

fight or you got to do this. It’s just not true. You don’t have to

fight your way through jail. It’s like anything in life. If you’re

not educated about the situation, it can be bad

We need a special unit in prison for only

the -LGBT. Some, some of them can’t be in population. They’re

scared to go to population to get raped or get stabbed. They could

separate the LGBT person from population, you know, put another

jail for them only. I seen lot of LGBT people in prison got beat

up, stabbed, all, all type of worse things happen to them

I think they need to start hiring more LGBT

more correction officers. Like LGBT, you can’t be a part of the

LGBT community and be a corrections officer, did you know that. Not

be openly gay. You can be an openly lesbian but you can’t be an

openly gay man and they let women, they put in areas where they are

not going to do any good. They put the women in non-visiting room.

They need to let female correctional officers to be up on the tiers

or in the dorms. They put the men up there and that is all corrupt.

They think it’s cute to see if the homo get beat up because they

don’t like

I believe that if people had better, like

if there was better planning for people that’s coming out, out of

prison system, a lot of them wouldn’t be going back to jail. A lot

of them would change their ways, and they would become productive

members of society, LGBT or not

|

|

2. Nondiscrimination and special population

considerations

And one of the things you were talking

about in jail that really needs to change, gays in prison should be

able to safely go to school. Right now they can’t. They’d be

attacked. In prison, they need to separate the jobs for older and

people that’s younger. I worked in a mess hall, and that’s a hard

job, and, you know, if you’re up in age and you got your, you know,

the older you get, the more aches and pains you have, you know, and

working in the mess hall, I don’t see it being good for somebody

that’s 55 or 60

They need to have senior citizen things up

there in prison for people that are senior citizens, I mean,

because when you’re old, I mean, everybody gets old. I mean,

already you’re forgetful in the mind and stuff like that. You get

senile and stuff like that, you know. Um, they should have just a,

I can’t say, um, a certain place, but, I mean, they should have

something for seniors too, you know, because - How can you put a

60-something year-old man in with the regular population of 15 and

16-year-old kids. I wish they would have places for people who are

of that age, something to do for them and something to keep their

mind on the right thing, you know, where they won’t get into

trouble or get hurt

|

|

3. Post

reentry access to culturally responsive safe and affordable housing

and social services

Cheaper housing, housing, affordable

housing, connected to a therapist, connection to treatment. All

these things—Affordable treatment because now, safe housing is

essential in being able to successfully adjust back into the

community. Living in a high crime area, that has a majority of

unemployed or underemployed residents that may be socially

stigmatized will reduce the ability to manage. In addition, some of

these areas have high rates of victimization of residents, and easy

access to illegal activities and drugs. Adding identification as

LGBT can exacerbate community discrimination and oppression

Housing is a big issue. Let’s say you’re

coming out of jail, and, and you’re eligible for SSI or whatever,

right? They should have some type of housing program that will meet

like the budget of a person that’s on SSI. I think that’s another

reason why a lot of people go back to jail because they feel safer

there, because at least they know that when the night comes, they

got somewhere to sleep. They got some food and they’re comfortable

with it, for some people

One thing that was really hard and I found

a couple of things when I got out of jail that were LGBT and the

housing situation. There was some terrible housing. And that’s not

just for the LGBT over 50, it’s the housing situation but it harder

for an LGBT person because like I said we are pushed into

mainstream and they’re not friendly. So having something housing

where it could be more LG affirm and I’m not saying build a big

house for only LGBT but at least let it be affirming where I can go

there and be okay and not go shopping and my neighbor come busting

my door because I’m gay and take my food because that happens

We need intergenerational services for LGBT

people. I work in a LGBT program and I think we’re from age 21 to I

think closer to 60. I see the age integration of the people. I

think we need to learn to live together even age differences

because that makes a community. To be able to respect or the, I

know when I grew up how I respected the older people. And I like to

be around the older people. And, and I help the older people and

that’s one of the things we need to get back into what a community

is integration of LGBT people of all ages

Specific services for people who are at

least age 50 or older, LGBT, and formerly incarcerated. For

programs, we need them more affirming. See everyone says we need

something for the gays, something for the, no, we need a firm thing

so we can integrate and learn to live

I would like them to have more places for

people that’s on the down low, or they’re not on the down low, just

gay. They just ready to come out or for the LGBT and stuff like

that, they need to have a lot more places for them, you know,

places where they could go and like TV and stuff like that, but I

don’t know how true, I never really, when I always went, I never

said I was gay, you know, so I didn’t get put with a gay guy. I got

put in the regular population, you now

For release programs, they really got to

somewhere to put people, aging LGBT people. Lesbian and gay people,

aging people they are just throwing them back in the street or

putting them in a house where there are mostly either sitting there

drinking or drugging or mourning themselves to death because they

are left in a room and they have nothing to do

|

|

4. Mental

health and social needs

More activities, more sponsoring of

something for the LGBT seniors. We don’t have anything. Even if

they go into regular senior citizen. Senior citizens are just like

kids. They are just bias as kids so, you know, just more resources

for us

We need a lot with diabetes because a lot

of our seniors are coming down with it, especially the black and

Puerto Ricans, because we are limited to our resources of eating

you know.

So if it is something that is available for

a closeted gay person, maybe his therapist or the counselor or

someone they have seen hears that or you suspect somebody, well you

know, they have housing for LGBT, here’s some information. I don’t

know if that applies for you, let me make that decision and then

tell you, you know what this is who I am and I like to keep it

between me and you so sign me up. But there should be some way that

it can get out because it is really stigmatized in jail. So most of

the men who are out there trying to be the biggest are the most

gay. But they are not going to say, you know, but then again they

don’t need the services because they going back to having a sexual

life and perform their self as a heterosexual person but there are

people that are in that are so, I think, I think there would be a

response because people, first of all, they will get this

information when they were out. Second of all, it will give them

some hope that I’m going to come out but I’m coming out for the

right reasons and I’m going to get some support and direction

|

|

5. Family

and peer and mentoring supports

To be able to integrate, you are going to

somewhere and have the same thing happen to you in jail going into

some of these program and housing and one of the things that I wish

they would offer more is support for LGBT coming out of jail

because if you can’t go home and most of them have been thrown out,

disowned, or, you know, families don’t associate with us and we

wind up going back to the streets doing what we did to get us back

in jail. If you identify, your family first of all if they are not

loving and caring to you like they should be, they are going to put

you out and once you get in jail, they don’t really have specials

cops to say okay don’t mess with the LGBT leave them alone. We are

not going to let you rape them. They don’t care

Start to have something for LGBT specific,

you know, supports. Okay and starting in prison. Yes because we

need to have that hope and have an LG person come to prison and say

hey, I’m out here, look at me. And I think that’s great when you

probably come up with a way to craft it. My only thought is does it

then put, if you have an LGBT person coming in, does that put

people at danger, people then become to know if they are LGBT

We need more coming out of jail for people

to know that there is hope like a role model thing. Like guys I’ve

been where you at but we can still get here. Don’t let your past

keep you suppressed. Look forward. Look up. Because we don’t get

that hope. We don’t get someone from the LGBT coming in jail saying

hey, guy I’m out there and I’m doing it. It’s not anything and

there’s no hope in jail saying that hey guy I got this place for

you that you can go to that’s just for you. We don’t get that. Now

they come in here and tell everybody that’s straight, we’ve got

this, this, this but we don’t have anything in jail coming out

saying well, we got some support lined up for you. Not yet and

that’s what needed because it’s frightening, like I said it’s a

revolving door. They don’t have this support, what are you doing,

you’re not equipping them to go out there and survive. You’re

equipping them to go back and come back

|

|

6. Justice

and policy advocacy opportunities

For policies, I would change stop and frisk

of course. And there is no law but their treatment of gays. They

have no respect for gays. There’s nothing in line that they can say

they are breaking and not doing, it’s just their treatments toward

especially the gay men, and I can’t even say lesbians. There’s very

few cops that will be angry with lesbians but all cops are angry in

treatment of gay people or trans people. It’s just horrible

One of the things that we should always

have is someone in the LGBT, in like on the returning is access to

a lawyer. They should have an LGBT person, affirming person to

defend us because we get no defense by regular attorneys. Now, I

mean that’s one time that will probably predict some things and

coming out we can work on that end but going in, I need somebody

like, they don’t even want to talk to you. We need yeah, LGBT

representation of lawyers, otherwise they may not want to talk to

you or really understand or help you

We need to have the opportunity to be more

visible and have our voices heard. What better way to let people

and professionals know what needs to change for LGBT elders

|

Policy Box 12.1

Review Table 12.2 of the chapter

appendix provides policy recommendations by and for LGBT elders to

improve service systems and organizational and legislative policies

that impact LGBT persons in prison and after their release. Choose

one of the theme areas: (1) adoption of more compassionate and

affirming practice and policy approaches, (2) non-discrimination

and special population considerations, (3) post-prison release

access to culturally responsive safe and affordable housing

services, (4) family and peer supports, and (5) justice and

advocacy opportunities. Provide at least 1–2 recommendations on how

organizational and/or legislative policies can be improved at the

local, state, federal, and/or international level to help improve

access to services and justice for LGBT elders in prison or after

their release. Develop an action plan on how to realize these

recommendations (e.g., building coalitions, advocacy campaigns,

contacting legislators).

Related Disciplines Influencing Service Delivery and Interdisciplinary Approaches

Based on the existing literature and

the current study findings, we recommend a holistic and

comprehensive social and public care response that targets primary

(prevention), secondary (at risk), and tertiary (targeted

population) assessments and intervention with LGBT elders at risk

of criminalization or current or past criminal justice involvement.

As illustrated in the first-hand accounts of formerly incarcerated

LGBT elders, they have had adverse experiences in service delivery

systems that include health care, mental health care, social

services, and the criminal justice system. Implicated in the

narratives of elders is the often less-than-adequate services and

sometime abusive treatment of law enforcement (e.g., police or

correctional officers), social workers and psychologists (in or out

of the prison), medical doctors and nurses, educators, and lawyers.

There are many factors that seem to account for the lack of

culturally responsive treatment of LGBT elder with criminal justice

histories, which include the fragmentation of services, lack of

communication between service providers, and lack for training to

work with LGBT elders that have multiple intersectional identities

that may include race and ethnicity, gender, HIV/AIDS history,

serious mental illness, substance use issues, and criminal offense

histories.

In general, there is a significant

need for affirming services in health and mental health, law,

social services, education and vocational training to help people

in the prison and community reintegration process. A comprehensive

response is needed to address the pervasive and multisystemic

biases, prejudice, and discrimination experiences of LGBT

minorities across the life course that places them at risk of

criminalization and/or involvement in the criminal justice system.

When LGBT elders feel that they cannot reveal their true identity

to access services they need in prison or in the community, it

leads to a disregard of their unique challenges by health, mental

health, and other service providers that would be instrumental in

accessing housing and financial resources. Fear of discrimination

and exclusion may lead to an avoidance of disclosure, and

therefore, a true evaluation of service is needed. This group tends

to remain marginalized and invisible to heterosexual social service

providers (Addis et al. 2009).

In the prior literature and current

study findings, access to education in prison or after prison

release is important. Both in prison and in the community, LGBT

people experience discrimination in accessing education. However,

in prison, this is even more so because many LGBT people in prison

did not attend or were not allowed to attend educational classes

because of personal safety and prison management issues. In the

current study highlighted in this chapter, clients who attend the

Rainbow Heights psychosocial club clearly described facing

discrimination from other service providers, such as medical

professionals, therapists, and social service providers, especially

with housing. In fact, many of the narratives suggest the visible

and invisible ‘prisons’ in which society attempts to place them.

One participant described how discrimination on the basis of LGBT

identities creates a ‘prison in the community’ and asked, ‘what’s

the difference from being in jail?’

A recovery approach is recommended to

assist LGBT elders being released from the criminal justice system

to feel more comfortable in accessing services for their mental

health, health, housing, and other important 'social, legal' and

other supports. Engagement without exacerbating stigmas of their

LGBT identity and criminal history is essential to begin

establishing a helping relationship. It is important to provide

services that consider diverse needs including, vocational,

educational, financial, clinical and housing services. The

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA

2012) has estimated that 12

percent of male offenders and 24 % of female offenders have a

mental health and/or substance use disorder. Many researchers

indicate that this may be even higher in the LGBT population (Brown

and Pantalone 2011; Mustanski et

al. 2010).

For any treatment to have efficacy, it

must treat the whole individual, not only the presenting disorder.

Best practices include addressing and integrating services with

culturally responsive providers. These services may include

supported employment, family education, peer support, case

management, and advocacy services. Organizations like The Rainbow

Heights Club, a self-help and advocacy program specifically

designed to provide services to LGBT individuals, may be a key

component in community reintegration (Hellman and Klein

2004). Places for socialization and

acceptance are crucial as one reenters the community from prison.

Isolation, discrimination, and lack of stable supports can only

have a negative outcome.

Mental health and other educational

and service providers need to provide trauma-informed care for

those reentering from the criminal justice system. To adequately

adjust to the community, people have to be taught strategies to

address traumas they have experienced and to overcome some of the

detrimental coping mechanisms they may have employed in the past,

which may include substance abuse. Partnering with criminal justice

professionals and working on a comprehensive culturally competent

unified plan is a first step in the process of managing complex

issues in reintegration. Entering the community without adequate

funds for food, shelter, and medical needs creates a barrier to

success, as does a lack of social support.

Lastly, consistent with Ka’Opua et al.

(2012), we recommend the need for

returning prisoners to have timely access to social service

programs and services as well as trauma-informed care to help cope

past trauma histories as well as the trauma of incarceration. For

more details on a trauma-informed approach, please see the

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (2010)

recommendations on trauma-informed care at: http://beta.samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma-interventions.

Summary

This chapter reviewed the experiences

of LGBT elders’ experiences prior to, during, and after

incarceration. The information that is available, including the

current study findings described in this chapter, suggests that

biases, discrimination, violence, and criminalization are common

experiences reported by LGBT elders. Intersectionality theory 'that

incorporates incarceration history as a social identity or

location, is an important consideration for developing

interprofessional and interdisciplinary practices across service

settings. As described throughout the chapter, many of these

diverse elders were not only LGBT but racial ethnic minorities with

histories of HIV/AIDs, serious mental illness and substance abuse,

trauma, and/or committed drug or serious violent offenses. A

holistic comprehensive approach is recommended that involves

interprofessional and intersectoral collaboration to address

service and policy gaps that are commonly experienced by LGBT

elders in prior to prison, during prison, and after release from

prison. Promising practices, such as the Rainbow Heights

psychosocial club in Brooklyn, New York, are highlighted as a

LGBT-affirming service provider that is helpful for LGBT elders

released from the criminal justice system.

Learning Exercises

Self-Check Questions

1.

Race, class, gender, and sexuality are

important in structuring our identity and that examining our

sexuality is integral to viewing the _________________ of the many

facets of self. (Answer: intersectionality)

2.

LGBT persons, especially elders, are

at high risk of direct violence in the form of _____________ and/or

_______victimization. (Answer: sexual or physical)

3.

_____________ research after gather

narrative data from participants to gain a in-depth portrait of

their lives. (Answer: qualitative)

4.

For LGBT survivors of trauma,

________________ is a recommended intervention strategy. (Answer:

trauma-informed care)

5.

For LGBT elders with serious mental

illness and substance use problems, a __________ approach is

recommended. (Answer: recovery)

Field-Based Experiential Assignments

1.

Visit a LGBT elder center or service

provider in your geographic location or attend a LGBT event, and

write about your experiences, especially as it relates to your

impressions of the LGBT community prior to the visit and after

it.

2.

Visit the United Nations-Free and

Equal Campaign located at and join the campaign: https://www.unfe.org/en. Review

the materials, including the fact sheets to learn more about the

human rights challenges facing lesbian, gay, bisexual and

transgender (LGBT) people everywhere and the actions that can be

taken to tackle violence and discrimination and protect the rights

of LGBT people everywhere. In essay form or in small group

discussion, choose one of the problems and the solutions to write

about or discuss: (1) LGBT Rights: Frequently Asked Questions, (2)

International Human Rights Law, (3) Equality and

Non-Discrimination. (4) Criminalization, (5) Violence, or (5)

Refuge and Asylum.

3.

View the short documentary on LGBT

elders released from prison short at:

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?v=10204217999038834&set=vb.1493049016&type=2&theater.

In essay form or group discussion,

describe your thought and feelings having watched this videos. Did

any of your viewpoints change after watching the video? If so,

please share in essay form or group discussion.

Multiple-Choice Questions

1.

Which country has the most number of

incarcerated people in the world?

(A)

Russia

(B)

China

(C)

India

(D)

USA

2.

LGBT elders are at high risk of what

types of discrimination and oppression?

(A)

Housing

(B)

Employment

(C)

Violence

(D)

All of the above

3.

Research that actively involves

participants voice in the research project is commonly referred to

as:

(A)

Quantitative research

(B)

Chi-Square Analysis

(C)

Participatory Action Research

(D)

Descriptive Research

4.

What percentage of incarcerated LGBT

people in US prisons report being raped:

(A)

75 %

(B)

35 %

(C)

12 %

(D)

64 %

5.

The USA spend about how much annually

to operate correctional facilities?

(A)

One million

(B)

Two and a half million

(C)

15 billion

(D)

77 billion

6.

Social documentary often is used to:

(A)

Foster dialogue

(B)

Stimulate debate

(C)

Stimulate social and institutional

change

(D)

All of the above

7.

Social Stigma among LGBT elders

involved in the criminal justice system can be experienced:

(A)

As a result of negative attitudes

about their LGBT identity and/or criminal justice involvement

(B)

Internally in the form of self hatred

and low self worth

(C)

Is not an issue

(D)

Both A and B

8.

Comprehensive services for LGBT

elders released from prison may included:

(A)

Housing and Employment

(B)

Access to health, mental health, and

social services

(C)

Histories of Trauma

(D)

A and B only

(E)

All of the Above

9.

For treatment to be effective with

LGBT elders with mental health issues released from prison:

(A)

Medication must be prescribed

(B)

It must treat the whole individual,

not just the mental disorder

(C)

Be GLBT affirming

(D)

B and C only

10.

An essential element or elements of

treatment with LGBT elder released from prison is the following:

(A)

Engagement without exacerbating

stigma

(B)

Child care availability

(C)

Offering space for socialization and

acceptance

(D)

Both A and C

Key

-

1–2-D

-

3-C

-

4-C

-

5-D

-

6-D

-

7-D

-

8-E

-

9-D

-

10-D

Resources

-

Be the Evidence International-Rainbow Justice Project: http://www.betheevidence.org/rainbow-justice-project/

-

Equal Rights Center: http://www.equalrightscenter.org/site/PageServer?pagename=issues_lgbt

-

Huffington Post Op-Ed on Prison Rape and Gay Rights: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/rodney-smith/prison-rape-gay-rights_b_4504331.html

-

Just Detention International: http://www.justdetention.org

-

Lamba Legal-Criminal Justice: http://www.lambdalegal.org/blog/topic/criminal-justice

-

Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) Resources Center: http://www.prearesourcecenter.org/about (Resources on LGBT persons in prison)

-

Prisoners of Age: http://www.prisonersofage.com/home

-

Rainbow Heights Club: http://www.rainbowheights.org

-

Sero Project: http://seroproject.com

-

Services and Advocacy for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual Elders (SAGE): http://sageusa.org/index.cfm

-

Transgender Law Center: http://transgenderlawcenter.org/issues/prisons

-

Transequality-Jails Prison Resource: http://transequality.org/PDFs/JailPrisons_Resource_FINAL.pdf

-

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: http://www.unodc.org

-

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Handbook on Prisoners with Special Needs: http://www.unodc.org/documents/justice-and-prison-reform/Prisoners-with-special-needs.pdf

-

United Nations-Free and Equal Campaign: https://www.unfe.org/en

References

Addis, S., Davies, M.,

Greene, G., MacBride-Stewart, S. & Shepherd, M. (2009). The

health, social care and housing needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual and

transgender older people: A review of the literature. Health and Social Care in the Community,

17(6), 647–656. doi:10.111/j.1365-2524.2009.00866.x

American Civil Liberties

Union [ACLU]. (2012). At America’s

expense: The mass incarceration of the elderly. Washington,

DC: Author.

Beck, A. J., Berzofsky, M.,

Caspar, R., & Krebs, C. (2013). Sexual victimization in prisons and jails

reported by inmates, 2011–2012. Retrieved September 18,

2014, from http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/svpjri1112.pdf

Brown, L., & Pantalone,

D. (2011). Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender issues in trauma

psychology: A topic comes out of the closet. Traumatology, 17(2), 1–3. doi:10.1177/1534765611417763.CrossRef

Bureau of Justice Statistics

[BJS]. (2006). Mental health

problems of prison and jail. Retrieved November 4, 2012,

from

http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/index.cfm?typbdetail&iid789

Carson, E. A. (2014).

Prisoners in 2013.

Retrieved September 18, 2014, from http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p13.pdf

Glaze, L. E., &

Herberman, E. J. (2012). Correctional populations in the United

States, 2012. Retrieved September 18, 2014, from