5. So What Is Quality?

The table linens were starchy white. The cutlery gleamed. The menus were sumptuous. My hosts and I, in one of the better restaurants in the Netherlands[1], pored over the abundance that was on offer. I made my choice, a straightforward one: a steak.

“And how would you like that done, sir?” asked the somewhat severe waiter.

“Well done,” I replied.

He looked blankly at me.

“That is not possible,” he said. “Choose something else. Fish, perhaps.”

Possibly the English accent was a giveaway. At least he had taken one step back from “fish and chips, perhaps.”

Herein lies one of the great realities on this earth, one that this pompous waiter and all too many in our world fail to grasp. Beauty truly is in the eye of the beholder. What is nectar to one palate may truly seem as poison to another.

For my part I am somewhat appalled to see blood seeping from a (to my perception) underdone steak. I savor the robustness of caramelized beef, especially when it has a rich depth of juicy fat at its rim. How I shiver to recall the time a well-meaning Japanese colleague invited me to his Tokyo home to honor me by serving shabu shabu, in which one is presented with strips of raw beef that you are invited to waft for a second or two in a bowl of hot water before deftly chop-sticking them into your mouth. How I cringe to remember the time that a Master Brewers Association of the Americas[2] organizing committee in Cincinnati decided that steak tartare was a good idea for a closing banquet.

And yet there are countless people around the world who rejoice in rare or raw meat.[3] Good for them. It is called tolerance. I will allow them their idiosyncrasies. But please, would you do me the courtesy of allowing me mine?

Each to his or her own. And so in the world of food I dismay at the invariable sneer that accompanies the words “British food.” It happens all too often here in the United States, a nation that of course gave the world such sophisticated dishes as peanut butter-and-jelly sandwiches and the hamburger. The first of these I detest, the second I adore (well done of course—I cringe when friends order such a minced beef concoction medium rare). Just, in fact, as I adore cockles (see endnote 4 in “Introduction”) and Heinz baked beans-on-toast;[4] and Cornish pasties;[5] and Lob Scouse;[6] and Ploughman's Lunches;[7] and tripe[8] (cold with lots of pepper and vinegar); and roast pork after the pork has been dipped in brine;[9] and of course the ultimate British triumph, curry.[10]

Who has the right to say that English food is naff? The French, with triumphs such as frogs' legs, snails, and fungi dug from the ground by pigs? The Germans, with vast lumps of meat, belly-swelling dumplings, and red cabbage?

It is easy, of course, to be sarcastic and demeaning in this way. Indeed, one might say that I am being hoisted by my own petard writing this way. I seek to make only the point that whether it is food or any other manifestation of this earthly existence, the beliefs, passions, and indeed, choices are endless. And who is to say what is good or bad? Let us be mindful here. Let us each respect and be tolerant of each other’s opinions.

And surely it should be this way with beer?

What Is a Good Beer?

I (and others) have written at length about beer quality.[11] But what exactly does it mean to the consumer? Most importantly, does anyone have the right to stamp their judgment on what constitutes a good product from a bad one? It is the way in the world of wine with the likes of Robert Parker and Jancis Robinson pontificating on what is and what is not a superlative purchase, thereby at a stroke launching the cost of certain vintages to otherworldly amounts.

As someone I know once said, “Don't you dare tell me, Charlie Bamforth, what a good beer is, just because you have a fancy job title and all those letters after your name. I happen to like my beer with tomato juice and chili and salt.”[12]

It works the other way, too. I lose track of the number of times that people have sneered at the famous United States lager brands. The reality is—in my opinion, of course—that these are some of the highest quality beers in the world for their sheer consistency from batch to batch. And you try hiding a defect in relatively gently flavored products. (Again, such would be what you perceive a defect to be, but let's say for the sake of argument it is a flavor that you do not expect to taste in that beer.) It is possible to hide a multitude of sins in a robustly flavored beer of deep roasted character and/or high hoppiness. Not so in a low carb US lager.

Let us journey then from the container inwards and dwell on attitudes towards what is and what is not beer quality.

The Container

I recall sitting in a Chinese restaurant in Sydney, Australia, and asking for a Tsingtao. It duly arrived, happily with a glass. But the beer was in a can. That felt wrong. Even to me, who has studied beer flavor and stability for many years and who knows full well that the beer inside will have been the equal of anything delivered in glass, it seemed cheap and out-of-keeping that a beer selected to accompany my succulent Szechwan should be enveloped in aluminum. Beer with food should come in a bottle—or at the very least drawn into a clean cool glass from a tap—but never in a can. Cans are for fishing trips or football games in front of the television.

Purely psychological, of course. Actually, beer is more stable in a can than it is in a bottle. The seal between the lid and the can body is totally gas proof. Not so for the bottle, where air will creep insidiously between the lip of the glass and the crown cork, the oxygen progressively changing the flavor of the beer in the direction of tomcat pee and wet paper. Okay, perhaps there are those of you who relish nuances of urine and cardboard in your lager. If that is the case, surely you expect those delights to be present in every glass? The problem, then, is that the beer flavor is changing. And so the young beer has one smell, but weeks or months later, it will be quite different. Is that not a quality failure? If such were the case in, say, gasoline, in that it fired up your truck wonderfully well when pumped soon after the tanker had delivered it to the forecourt but a few days later it served only to seize up your engine, then you would be less than completely satisfied.

Provided the inside of the can is properly lacquered and there is no opportunity for metal to contact the beer, then the product will be considerably more stable in a can than in a bottle. And as is the case for bottling, there are big efforts to minimize how much air does reach the beer during filling. Nowadays brewers can buy—at a price—oxygen-scavenging crown corks. And a company like Sierra Nevada has turned back from twist-off caps to pry-off ones, simply because they allow less gas to pass.

Brewers are also well aware of another problem with crown corks, that of scalping. The wonderful hoppy aromas associated with some beers can be progressively lessened by the responsible oils adsorbing onto the coating of the caps. This does not happen in cans.

In 2005 I was interviewed in the San Francisco Chronicle. I was asked: “If there are 50 beers on tap, what do you order?”

I answered, “Something out of a bottle.”

The interviewer, Sam Whiting, frowned. “Why?”

“Because,” I said, “if there are 50 beers on tap I worry that they are not being moved through those pipes as quickly as they should be.”

If I go into a bar proudly displaying tap after tap, I invariably ask “which is your best seller?” At least there is then a chance of that brand being relatively fresh.

This presupposes that the bar staff know how to clean their lines. Once I was with my wife in a sports bar in the suburbs of Portland (not my customary type of haunt, but we seemed to have hit a culinary wasteland). I ordered a Bud. I took one sniff of the headless lemon liquid and detected the reprehensible (to my mind) diacetyl. This is the whiff of butterscotch, of popcorn (the smell that keeps me out of movie theaters). Now you need to know that my wife is continually berating me for not complaining in restaurants, but not this day. I called the waiter over and said, “I can tell you that this beer will not have tasted like this when it left the brewery.”[13] Chewing, she looked at me coldly. “Then choose something else.” My wife was relieved that I did not follow with, “Do you know who I am?”

The simple fact is that vast volumes of deficient beer are served on tap in bars the world over. Hygiene, hygiene, hygiene is the indispensable mantra—otherwise, the beer itself will most definitely be indispensable.

There have been dubious practices since time immemorial with beer on tap. In the day in UK, the standard practice was to put the dodgy beer on tap in pubs close to football grounds on Saturday afternoons. That was the time to unload questionable product into the bellies of men and to a lesser extent women distracted by their soccer passions.

As an 18-year-old trainee barman, I was instructed by George, mine host of The Brown Cow in Helsby,[14] how to deal with the slops that spilled over from the pouring of pints from tap handles. Beneath every tap was a tray, into which the surplus foam and beer was collected as it unavoidably streamed down the side of the glass as a full pint with requisite foam-atop was delivered. When the trays filled, we tipped them into buckets, which were progressively collected down in the cellar. George told me that the trick was always to put the contents of the buckets, which of course emerged from barrels of several types of beer, into the barrel of mild ale. That was the darkest and least likely to reveal that it has been adulterated. For the longest time I would never buy a pint of mild anywhere I went.

Speaking of English ales, there is of course the matter of warmth. For such is the popular perception: The English drink warm beer. It is, of course, a myth. Traditional English cask ales are usually dispensed at cellar temperatures— although you still may be fortunate enough to find an old-fashioned hostelry where the barrels are positioned behind the bar. Cellars are below ground, and (in case you did not know it) England is not the warmest country on the planet, and it’s pretty darned cool beneath the earth. So the classic serving temperature for cask ale is 12°C to 14° C (53°F to 57°F) (see footnote 49 of Chapter 1).

The Foam

In 1989 I founded the European Brewery Convention Foam Sub-Group, a collection of scientists from across Europe (and North America) who studied bubbles.[15] Sad, you might think. The boffins coming from Germany and Belgium dwelt upon the irony that the chairman was English. For they, like so many non-British, believed that to visit London was to visit the nation. And there, of course, the ale is like tepid tea. Beer of low carbonation is bled into glasses that are exactly a pint from bottom to top and therefore to satisfy the frugal Londoner, there is space only for liquid beer and little (if any) foam.

Such is indeed the norm for cask-conditioned beer in London. But that is certainly not the case farther north. The foam is de rigueur in Newcastle and Sheffield and all over the rugged north, both sides of the Pennines. And for the Northerner (especially in Yorkshire) being more money-minded than the “soft” Southerners, then to satisfy the twin demands of a full pint and a substantial foam there is a need for oversized glasses, with a line to mark one pint of liquid, but with space atop for the head.

Questions have been asked in Parliament about it,[16] such is the passion of many Britons[17] for a creamy froth. For they are indeed influenced by the appearance of foam.

At Bass we quickly learned this. If we did an in-trade trial comparing two beers and were testing for which had the preferred flavor, then the one that had the best head always came out ahead. People drink with their eyes.

The first thing I did on joining the faculty at UC Davis was an experiment on foam perception. We took cans of a single brand of beer and poured it in a myriad of ways. This illustrates the point that you can create all manner of foam appearances depending on how vigorous the pour is and how rapidly you drain the beer on drinking.[18] More leisurely sipping leads to more foam lacing the side of the glass. Sam Woo photographed the beers immediately after dispense, after half of the glass contents had been siphoned off, and then the empty glass that featured only residual foam. When John Smythe and I showed the photographs in various combinations to people, the overwhelming observation was that beer with good foam scored better.[19] People thought it was better brewed and would taste better. Even folk who confessed to the (to my mind) heinous crime of quaffing their beer straight from the bottle or can were prepared to admit that beer with a foam looked better. The only aspect of the foam that fetched disagreement was the cling. Whereas most men liked to see foam sticking to the side of the glass, many women didn't.[20] They thought it looked dirty and was a sign of a grubby glass. In fact the opposite is true.

There is a sidebar to these experiments. Anheuser-Busch, who endow my professorship, had invited me to St. Louis because they were donating me a slew of instrumentation to stock the dark-ages laboratory that I had been bequeathed in

Davis.[21] While in St. Louis I was invited to make a presentation, and so proudly showed my photographs. Top man (in every way), the very excellent Doug Muhleman, fired the first question. “That's very interesting, Charlie,” he said in his deep Southern Californian tones, “why d'ya use Miller beer?” I had not revealed the identity of the lager used, but it was indeed Miller Genuine Draft. Miller pioneered the use of modified hop preparations that protect its beer against skunking, which otherwise is inevitable in the clear glass bottles that it champions. A side impact of these hop preparations is that they give really stable foams, to the extent of being too coarse to the eyes and minds of some.

Of course, foaming can be overdone. Which of us has not opened a bottle or can of beer and recoiled at the sight of the contents spontaneously spewing forth, drenching our pants and sorely trying our patience? One explanation is that at some point in the recent past the container was dropped or, worse still, deliberately shaken by a so-called friend with a bizarre sense of humor. Relax, breathe. They are all God’s children.

Even more insidious is over-foaming caused by materials in the beer that potentiate this “gushing.” These can be of various types, but most commonly it is the fault of a small protein produced by a mold called Fusarium that contaminates grain under adverse growth and climatic conditions. Fastidious maltsters and brewers will never use contaminated grain.

The Clarity

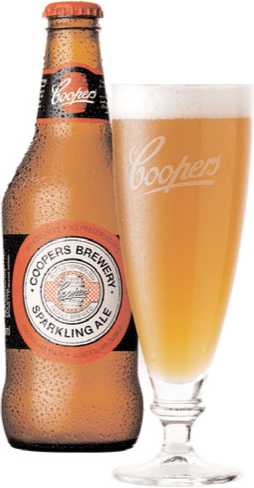

It was my first visit to Australia and I was in a bar in Brisbane. I chose a Cooper's Sparkling Ale (see Figure 5.1). The cheery chap behind the bar pushed the beer across the bar at me, and

I lifted it to eye level with a frown. “Excuse me,” I said, “but I think there is a problem. This beer is cloudy.” His smile disappeared, “It’s supposed to look like that.” And under his breath he added “pommy bastard.”[22]

Figure 5.1 Cooper’s Sparkling Ale. With thanks to Tim Cooper.

A solid reminder: Not all beers are “bright.” Most are, and in these any sign of turbidity is often construed as something growing in the beer, whereas in reality it is far more often due to something nonliving dropping out of solution. By no means, though, are all beers clear. Most notable of course are the hefeweissens, splendid beers best served over a breakfast of white sausage and pretzel in Germany. Hefeweissens are turbid because they retain their yeast (hefe). Some such beers are filtered and are therefore “bright.” These are the krystallweizens.

The key for turbidity, just as for all other elements of beer quality, is surely an appearance consistent with what you expect. If the beer is turbid, then for goodness sake, ensure that it is always similarly turbid. If a beer is intended to be crystal clear, then ensure that such is always the case.

Over time, beer will develop cloudiness and perhaps sediments due to a number of causes, most frequently reactions between certain types of proteins from the grain reacting with tannic materials from the grain and hops.[23] This will be exaggerated by storing the beer too warm and too cold (never freeze beer). Brewers have got very good at ensuring that they remove these sensitive materials during processing, and so clarity problems are few and far between in this day and age.

Perhaps the most poignant example of what a clarity problem can mean was with Schlitz. Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company was founded in 1849 in Milwaukee. Schlitz was “the beer that made Milwaukee famous.” It was the second biggest brewing company in the United States in 1976, at a time when it started to spread the word in the corridors of power that it was going to use its technical innovation superiority to surge ahead of the opposition. Invest in us! It started to accelerate fermentations, but the big bugbear was an unrelated clarity problem arising from the interaction of two process aids added in inappropriate juxtaposition. Put more simply, the Schlitz got “bits”: white flakes that made the beer look like a child's snowglobe that you tip over and watch the snowflakes fall. There were other problems around the brewery, not least a crippling strike, but the perception was that here was a company that had little concern for its customers. The brewery was sold to Stroh in 1982, the latter being swallowed by Pabst in 1999. In recent years the Schlitz brand has reappeared; retro rules, as we have seen.

The Color

The color of beer is primarily determined by the amount of darker malts employed in the brewing grist. The more intensely malt is dried (see Appendix A, “The Basics of Malting and Brewing”) the more color (and intense flavor) it develops. Color also arises through the oxidation of tannic materials in the grist—the same chemistry as occurs during the browning of a sliced apple. Therefore by controlling the grist and by controlling how much air gets into the brew, brewers can control color.

There is a saying in my native Lancashire: “Once every Preston Guild.” The Preston Guild is an infrequent civic occasion, and the saying points to its less than regular occurrence. One time, however, it coincided with my stint with Bass, and we had a display there. One of my team, Kim Butcher, for reasons that elude me at this distance in time, decided to test out a hypothesis that folks not only judge beer flavor on its foam and clarity, but also on its color. Kim put some flavorless food coloring into Carling Black Label (the biggest selling brand of beer in UK) and made it look like an ale. When we tasted the unadulterated lager and the color-adjusted beer “blind” there was no significant flavor difference. But when folks in Preston tasted the two beers they ranked them very differently. The beer with the extra color was deemed more “ale-like,” with notes such as astringent, burnt, bitter, malty, diacetyl, full, and heavy singled out. What better testimony of the need to control color. Conversely, what more fascinating a reminder that one could deliver brand differentiation downstream simply by adding color. This can be achieved by adding caramel to the beer, of course, but most brewers would prefer to use water extracts of roasted grain that are fractionated to separate the color from the flavor. Using these extracts a beer can be “colored up” without changing the flavor (and vice versa).

The Flavor

I am always baffled when people say to me, “I don’t like beer,” for they might just as easily say “I don’t like food.” For the reality is that there is a seemingly endless range of beer flavors and styles.

I have concluded on being greeted after my public talks with this negative view of beer, that the only people who will admit to it are women (perhaps they are more honest) and that for many of them the problem is gas.[24] I am of course speaking of the carbonation of beer, rather than any metabolic consequence pursuant to the consumption of ales and lagers. I guess I can see this point of view, assuming of course that the selfsame people equally disdain Coke, Pepsi, and Seven-Up, which are more highly carbonated than any beer. And the answer of course is to select a low-carbonation beer—such as a draft ale or stout in a can. Or, to pour with vigor and swirl.

Even then, so many of these beer naysayers will say, “Oh, it’s more than just the bubbles. I don’t like the taste.” I can see why a roasty stout or a double-hopped IPA might be a challenge (they are for me sometimes). But a low-carb North American light lager? That’s hardly going to offend the senses. Some would say the taste trends towards zero. That I feel would be a tad extreme, but certainly these products do not overwhelm the senses. Having said which, take a look at the biggest selling beers in the world: None of them has extremes of flavor. They reach the common denominator, which is the great majority of people who do not like to have their taste buds and nostrils blitzed by beer or any other component of the diet.

In Appendix B, “Types of Beer,” I journey through the enormous diversity of beer styles. Rather more than the red, white, and pink of wines, would you not agree?