4. On the Other Hand: The Rebirth of a Beer Ethos

I had never before met Ken Grossman, the owner of Sierra Nevada Brewing Company (see Figure 4.1). It was the spring of 1999, and he invited me to travel the 100-or-so miles from Davis to Chico to come talk about beer freshness with his team. The room was packed with brewers senior and junior, quality assurance personnel, and who-knows-who-else in the impressive bunch that Ken had assembled. And there was Ken, I assumed to take a back seat role as his technical team pumped me for information. But it was Ken who kicked things off with the immortal question, “So, Charlie, what do you think about electron spin resonance spectroscopy?”[1] As he fired question after question at me I was learning very quickly one of the main reasons why his company had grown so phe-nomenally—and why it produces beer of a quality that is at least the equal of any other brewing company I know.

Figure 4.1 Ken Grossman when awarded an Award of Distinction by the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences at UC Davis in 2005. (Left to right: Michael Lewis, Ken Grossman, the author.)

Later that day, I delighted in conversation with Ken over lunch in the first-rate restaurant that adjoins the brewery. He insisted that I try the beer sampler, in which small portions of the many worthy brews of the company are presented to the customer. I tried them all—and recognized each in its own way for its excellence, but I felt obliged to say, “You know, Ken, some of your beers are just about at my upper limit for hoppiness.” He calmly looked back at me and, with the glimmer of a smile on that bearded face, replied, “Charlie, 25 years ago I was brewing in a bucket. Now I am producing more than 500,000 barrels every year[2] and selling into every state in the nation. Do you mind if I leave things as they are?”

Sierra Nevada is indeed a phenomenal success story. Ken Grossman was born in Southern California and developed very early interests in matters technical. He was only 11 years old when he built a guest house annex to his parents’ home and was not much older when a neighbor interested him in fermentation processes. He repaired electrical and electronic appliances. Moving to Chico in 1971, he combined employment in a bicycle shop with studies at Butte College and California State University, Chico (he never did graduate), and he opened a home brew and winemaking retail store. At college he enrolled in classes with workshops and was able to construct his first brewery (co-owned with Paul Camusi), including drilling all of the holes in the false bottom of his first lauter tun. By day he studied, by night he brewed, and then he would walk the streets of Chico, going from bar to bar endeavoring to interest them in the local ale, with its distinctive grapefruit-like aroma due to the Cascade hop. The Sierra Nevada Brewery was named for his favorite hiking and climbing territory and opened in 1980.

Ken will tell you that it was a struggle, requiring that he and Camusi return several times to friends and family to borrow money to keep the dream alive. He searched dairies as well as breweries the length and breadth of California and even as far away as Germany, to find vessels that he could use or modify as he sought to nudge the production volumes forward. Ken could not afford the carbonator that most breweries employ to bring the finished beer to the specified carbon dioxide level. So he resorted to natural conditioning, the approach that he adheres to to this day, and another special element of the Sierra Nevada package.

There is surely not a feel-good story anywhere in the world that does not feature somewhere a remarkable coincidence, unlikely event, or unexpected turning point. For Sierra Nevada it was when a San Francisco Examiner journalist wrote a piece about them in the Sunday color magazine— accompanied by a photograph of Ken and Paul perched on kegs on the front cover—at the time that the beer buyer for the Safeway supermarket chain visited his Chico State-enrolled daughter and fell in love with the Pale Ale. Sierra Nevada was off the blocks and running. Fast.

As volumes grew, so did the wily Grossman progressively increase the sophistication of his facility, in due course moving to a new plot with enormous scope for expansion on East 20th Street. And now, years after buying out his partner, it is the seventh largest brewing company in the United States and truly the most beautiful facility in the world: gleaming copper vessels, hand-painted murals on the brewhouse wall, intricately designed porcelain tiles in the corridors, the very latest in fermenter and packaging capability, a fleet of delivery trucks, a rail link that delivers malt direct to the silos from Canada.

As well as being role models for excellence in brewing, Sierra Nevada is also ahead of the game environmentally. Its commitment to green issues spans from the very simple to the sublime. It stresses the importance of recycling the fundamentals: office paper, cardboard, glass, stretch wrap, plastic strapping, construction materials, pallets, and hop burlap. It seems that in 2006, Sierra Nevada avoided sending 97.8 percent of its total waste to landfill. Sierra Nevada was one of the first regional breweries to employ a vapor condenser to recover energy from the kettle, diverting it to preheat process water. It has effected a modernization of its boiler systems to increase energy efficiency and minimize emissions. It has installed electronic ballast lights and motion sensors, has replaced air compressors with ultra-efficient, speedcontrolled drives, and is employing high-efficiency motors and refrigeration systems throughout the facility. Sierra Nevada has cut water usage by approximately 50 percent. It treats all production wastewater to reduce the Biological Oxygen Demand[3] burden on the local municipality, using a sequential anaerobic/aerobic treatment plant.[4] The methane that is generated feeds fuel cells: four 250-kilowatt co-generation power units generating one megawatt of power that satisfies most of the brewery's electrical demand. Co-generation boilers harvest waste heat and produce steam for the system.

The energy efficiency of the installation is double that of grid-supplied power, and air emissions are substantially reduced. The spent grains and trub are fed to cattle that are ultimately transformed into fabulous steaks served in the restaurant adjacent to the brewery. En route, their manure fertilizes Sierra Nevada's experimental hop yard. Small wonder, then, that Sierra Nevada has been celebrated in the Waste Reduction Awards Program of the state of California annually for the past seven years.[5]

Oh, and the beers truly are great. But what would you expect from a man who knows how to do things right—a humble man, who fully acknowledges how the likes of AnheuserBusch helped him with technical advice as he set out. Don't look in the direction of Chico if you seek to have support for your prejudices against the “big guys.”[6]

For inspiration, though, Ken Grossman's role model for the brewing dream was Jack McAuliffe (see Figure 4.2).

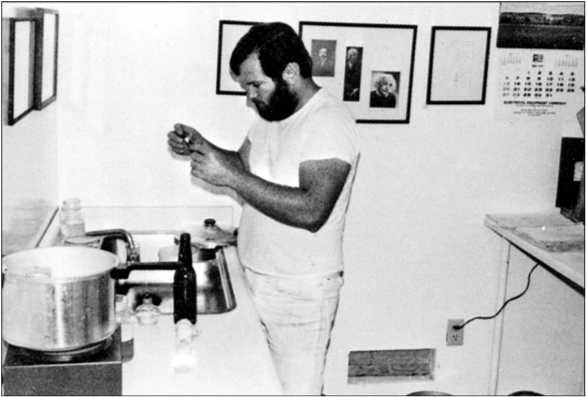

Figure 4.2 Jack McAuliffe in the lab at New Albion (note the picture of Albert Einstein on the back wall). With thanks to Sierra Nevada Brewing Company.

In the sixties McAuliffe lived in Dunoon, Scotland, working in the maintenance crew on US submarines. There he fell in love with the local ales and became a home brewer, reading avidly and motor biking extensively in Europe to glean whatever he could about brewing. Upon returning to California in 1968 he went to university before becoming an optical engineer. He remained at his most passionate when pondering matters brewing. Being of an engineering persuasion, he was able to fabricate a brewery in 1975 in the heart of wine country in Sonoma.[7] With a hodge podge of adapted vessels and his mechanical aptitudes sufficient to enable him to construct a simple mill and renovate defunct apparatus, he developed the New Albion Brewing Company, named for the land north of San Francisco Bay described by Sir Francis Drake.[8] The first brews were in 1977, with water trucked down from a nearby hillside. Production was less than ten barrels a week. New Albion lasted but five years, succumbing to the seemingly impossible challenge of carving a niche in an industry dominated by behemoth brewers. Others, like Ken Grossman, overcame the odds. But their inspiration was the big bearded McAuliffe (see Figure 4.3). McAuliffe also inspired the small staff that worked with him. Men like Don Barkley (see Figure 4.4), UC Davis alumnus, who started with New Albion for a wage of a case of beer a week and whatever he felt that he needed to consume while in the brewery. And he learned much, subsequently put to great effect as the brewmaster at the Mendocino Brewing Company, first in Hopland and then Ukiah, with his fabulous Red Tail Ale, and more recently the Napa Smith brewery, rejoicing in the production of a splendid range of beers in the heart of snobby wine country.

Jack McAuliffe and Ken Grossman built their own breweries. Fritz Maytag (see Figure 4.5) pursued a different model.

Figure 4.3 Ken Grossman and Jack McAuliffe sharing memories. With thanks to Sierra Nevada Brewing Company.

Figure 4.4 Don Barkley and the author. With thanks to Diane Bamforth.

Figure 4.5 Fritz Maytag. With thanks to Anchor Brewing Company.

It was the summer of 1965 in San Francisco, and 28-year-old Fritz Maytag, a liberal arts graduate from Stanford and great-grandson of the founder of the famed appliance company, would take lunch at the Old Spaghetti Factory in North Beach. He delighted in drinking a beer on tap called Anchor Steam. Talking one day to the owner of the restaurant, Fred Kuh, he discovered to his chagrin that the brewery was about to close its doors. He hot-footed it down to 8th Street and discovered a facility that was (in Fritz' own words) “the last medieval brewery” and (as he would soon discover) a microbiological nightmare. The company's bank was in the black to the tune of $128.

Naturally, Maytag, who is as much philosopher as he is visionary, fell in love with the place and purchased 51 percent of the business on September 24, 1965. In 1969 he became sole owner, and over a ten-year period breathed new life into the company and its flagship brand.

Fritz Maytag adores history and delighted in the rich tableau that represented the emergence of this San Francisco iconic brewery. Its origins were in the Gold Rush and a German brewer called Gottlieb Brekle. It was the next owners, Ernst F. Baruth and son-in-law Otto Schinkel, Jr., who first used the trade name Anchor. The product was a steam beer, so-called for beers brewed on the west coast using bottom-fermenting lager yeast in the absence of plentiful ice.

The brewery was destroyed in the fire that succeeded the 1906 earthquake, soon after Baruth died suddenly. A year later Schinkel was thrown from a streetcar and killed. Other German brewers Joseph Kraus and August Meyer kept the beer alive before Prohibition closed the business down in 1920. When repeal came, owner Joe Kraus began brewing Anchor Steam again on a new site, at 13th and Harrison, only for another fire to destroy the premises a few months later. Kraus reopened the brewery at 17th and Kansas, just a few blocks from where the brewery is today, and gained a new partner in Joe Allen, who did his best to keep things alive, but bowed to the seeming inevitable in July 1959 and, in the face of the burgeoning might of the nation's megabrewing companies, closed the company down. Enter Lawrence Steese, who bought Anchor and reopened it in 1960 on 8th Street. The struggles continued—until Maytag arrived on the scene.

After steadying the ship, Fritz commenced bottling the brand and launched a series of other beers that are alive and kicking today: Anchor Porter, Liberty Ale, and Old Foghorn. He also produced the first of his celebrated Christmas Ales, with a different and closely guarded recipe every year. And the growth presaged the final shift of scenery in 1977: to an old coffee roastery on Potrero Hill. By 1993, Anchor became the first brewery in the world to have an in-house distillery, making a splendid rye whiskey and a gin.

One of the first things that Fritz Maytag ensured was that he had a laboratory, recognizing that successful brewing is very much dependent upon the application of sound scientific principles. He read Pasteur's Etudes Sur La Bier, alongside other seminal brewing texts.[9] He peered relentlessly into his microscope to assure himself that his determination to eradicate the microbiological nightmare that had almost brought the previous regime to rack and ruin was working. Maytag was justly identified as an icon of the brewing revolution in the United States, with his readiness to help and advise others and his passionate exploration of brewing ancient and modern.[10]1 confess to a kind of sadness to learn on the very day this manuscript was finished in April 2010 that Fritz Maytag had sold his brewery. The king is dead; long live the king.[11]

Years after the Stanford graduate Maytag had first inspired Californians (and many beyond) to brew beer, a trombone-playing engineering student from the University of California's Berkeley campus who had spent months interning at Anheuser-Busch's Fairfield brewery after a boyhood touring Europe drinking beer (by permission) with his family decided to head to the legendary brewing school at Weihenstephan.[12] Dan Gordon (see Figure 4.6) was the first American to graduate the class on the Freising campus, and he returned to his native San Jose determined to make great lagers according to the Reinheitsgebot traditions.[13] He succeeded, having partnered with restaurateur Dean Biersch (“front of house” to Dan's “back of house” as Dan puts it). The pair opened their first brewpub in Palo Alto in 1988, and the Gordon Biersch legend was born. There are Gordon Biersch brewpubs all over the land—and as far afield as Taiwan. And on East Taylor Street in San Jose lies the main production brewery that delivers a rich array of bottled lagers of every type, year-round and seasonal brands alike, to outlets far and wide. Dan Gordon is a larger than life character in every way. 'Twas he who coined the phrase “never trust a skinny brewer,” delivered with his infectious laugh. And it was also Dan Gordon who invented that culinary mainstay of the nation's sporting concessions, the garlic fry.[14]

Figure 4.6 Dan Gordon. With thanks to Gordon Biersch.

Ken Grossman and Fritz Maytag advanced the model of the finest ale brewing, primarily for distribution nationwide. Dan Gordon's model was lagers (and some Germanic ales; for example, his splendid hefeweissen), either brewed in the main brewery for distribution or locally in restaurants bearing the Gordon Biersch logo. Jim Koch, on the other hand, started in Boston, Massachusetts with a franchise brewing approach, underpinning an appeal to US drinkers to be loyal to the flag with their beer selections (see Figure 4.7).

Figure 4.7 Jim Koch in 1986. With thanks to Boston Beer Company.

Koch, a native of Cincinnati and from a brewing family, studied in the law and business schools at Harvard. Struck by the growing sales of imported beers, Koch invested $100,000 of his own money and $140,000 from friends and family in establishing the Boston Beer Company in April 1984. He was 33 years of age. He dug out a time-honored recipe from his great-great-grandfather, Louis Koch, who had been a brewer in St. Louis, a brew adhering strictly to the Reinheitsgebot, and he contracted with the Pittsburgh Brewing Co. to produce it with the name Samuel Adams Boston Lager. He bought a truck and distributed the beer himself in Boston.

In 1987 the beer started to be sold in Manhattan, and a year later he used $3 million from an investment bank to buy an old Boston brewery, though he was stymied by the challenging costs demanded to fill the location with the necessary equipment. It became a tourist location to promote the beers and a center for research and development.

As the 1990s opened, the beer spread into Washington, DC, Chicago, and the eastern states following an agreement for the beer to be produced under franchise by Blitz-Weinhart in Portland, Oregon, a long way from the principal market, although the Samuel Adams Brew House was also opened in Philadelphia.

Koch's marketing strategy played heavily on national loyalty, urging people to drink a fine, fully flavored product from the US rather than imported products. Slogans included “Declare Your Independence from Foreign Beer.” They drew attention to the shortcomings with imported beer, namely the fact that beer goes stale if too much time has elapsed between packaging and consumption. The beer scooped a number of awards at the major beer festivals, though his marketing angle irritated not only European breweries importing into the US,[15] but also other brewers in the craft sector. It wasn't long before the big US brewers also started to see the likes of Boston as a major threat.

Production was 714,000 barrels in 1994, and a year later the company went public. By the end of 1995 output had soared to 961,000 barrels, with brands now including Boston Lager, Cream Stout, Honey Porter, Triple Bock, Cranberry Lambic, and a Winter Lager.

In 1997, they purchased the Hudepohl-Schoenling Brewing Co. in Cincinnati, a location that had been brewing its beer under contract, as well as an abandoned brewery in Boston, seeking to dispel criticism that the famed Boston beer was brewed a long way from home. The beer was being brewed in a diversity of locations, including Pittsburgh Brewing Co., F. X. Matt, Genesee, and Blitz-Weinhart. The product range was starting to be exported, and indeed brewed under license at locations such as Whitbread in England.

Small wonder that they now launched Samuel Adams Boston IPA, a beer with a pronounced English provenance.[16] And very soon they joined the light beer momentum with Samuel Adams Light. Nowadays two-thirds of the beer is brewed in Cincinnati.

But what of the home brewer? Here, surely, the doyen is Charlie Papazian (see Figure 4.8). Papazian was a nuclear engineering student at the University of Virginia when he began home brewing. Going to teach in Boulder, Colorado, he continued to brew his beer, spoke about his passion in courses at the Community Free School and wrote a pamphlet to encourage others to take up the hobby. In October 1978 President Carter signed into legislation the freedom for people to brew beer at home,[17] and two months later Papazian founded the American Homebrewers Association, together with the Zymurgy newsletter. In spring 1981 he sponsored a brewing conference, which morphed in due course to the Craft Brewers Conference. In May 1982 he launched the Great American Beer Festival, and in 1983 the Institute for Fermentation and Brewing Studies, which would become the Association of Brewers, with its journal the New Brewer. These days all of the Papazian operations are within the umbrella of the Brewers Association, with a sizeable staff, a large publishing portfolio, and an ongoing commitment to champion beer, for those operating in their own homes all the way through to the biggest breweries in the craft beer sector.

Figure 4.8 Charlie Papazian. With thanks to Charlie Papazian.

To attend the Craft Brewers Conference or the National Homebrewers Conference is a delight. The atmosphere is humming with bonhomie. The delegates are sponges for both information and beer. The joie de vivre is tangible, the empathy inspirational. Here is a joyous, almost spiritual celebration of malt, hops, yeast, and water. The only disagreeable moments come when someone tries to take a pot shot at the “big guys,” who seem to be, for some folks, the devil incarnate. Such attitudes are surely wrong, for brewers in companies of all sizes are united in their determination to produce great beer.

Which leads us to the question: What does quality mean in beer?