7

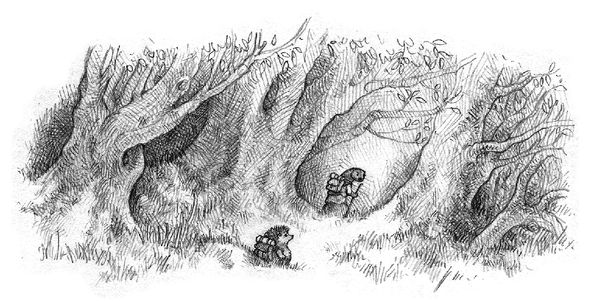

Young Uggo Wiltud soon found that Jum Gurdy’s bark

was not serious, and his supposed bite was nonexistent. The young

hedgehog knew that the otter, despite his forbidding size and

appearance, was quite easygoing. Together they trudged off along

the path, cutting across the ditch and travelling west through the

area of Mossflower woodlands which skirted the vast flatlands.

Midmorning saw warm sun seeping through the leafy canopy of oak,

beech, elm, sycamore and other big trees. Soft, loamy earth was

sprouting with grass, young fern, cowslip, primrose, silverweed,

milkwort and alkanet. Birdsong was everywhere, echoing through

patches of sunlight and shade.

None of this was of any great interest to Uggo,

whose stomach had been telling him of his need for food all

morning. Jum, who had been forging doggedly ahead, turned to the

young laggard in his wake. “Are ye weary already, Master

Wiltud?”

The reply was loud and swift. “No, I’m ’ungry,

Mister Gurdy!”

Jum nodded at the sky. “Sun ain’t reached midday

yet. That’s when we stops for lunch. Keep goin’ awhile yet.” He

carried on.

Uggo followed, but not without complaint. “Huh,

’tis alright for you, Mister Gurdy. You ’ad brekkist back at the

Abbey, but I never, an’ I’m starvin’!”

The otter leaned on the lance he used as a

travelling stave. “Ho, dearie me, pore liddle ’og. Wot a pity ye

can’t go sneakin’ off down t’the kitchens a-stealin’

vittles.”

Uggo stuck out his lower lip surlily. “Wouldn’t

’ave to. There’s always summat t’be ’ad round Redwall. You only’ave

to ask nicely.”

Jum made a sweeping gesture with his stave. “An’

wot about ole Mossflower, eh? There’s plenty t’be ’ad around here

without even the askin’!”

Uggo chanced a scornful snort. “Hah! Like

wot?”

The big otter cast swiftly about, then pulled a

stem with yellow buds adorning it. “Like this. Try it.”

The young hedgehog took the stem, sniffed it, then

took a tentative nibble. “Tastes funny—wot is it?”

Jum shook his head pityingly. “You young uns are

too used t’bein’ carried round an’ gettin’ vittles served up on a

platter. That’s young dannelion, matey. I ate many a stem o’ that

when I was yore age. Now, try some o’ these.”

He gathered various pieces of early vegetation,

feeding them one by one to Uggo and explaining.

“This is alkanet—taste like cucumber, don’t it? Try

some coltsfoot. Nice, ain’t it? This one’s tutsan, good for ye.

Charlock, sweet Cicely. There’s all manner o’ vittles growin’ wild

in the woodlands. No need t’go ’ungry.”

Uggo chewed gingerly, pulling a wry face at the

bitter flavour of one particular plant.

“T’aint the same as proper food, though, is it,

Mister Gurdy?”

Jum snorted at the lack of gratitude. “Maybe not to

yore way o’ thinkin’, but ’twill keep ye goin’ until lunchtime. Now

stop moanin’ an’ git walkin’!”

When midday eventually came, Jum was secretly glad

of the rest. He had aged, and he had put on weight being in charge

of Redwall’s Cellars. It was some while since he had undertaken a

journey to the coast. Careful not to let his young companion see

that he was tired, the big otter put on a springy step.

“Keep up now, Master Wiltud. Yore fallin’ behind

agin!”

Uggo was not in a good mood. He pointed angrily

upward. “You said we was goin’ t’stop for lunch when the sun

reached midday. It did that some time ago, an’ you ain’t stopped.

Wot are we waitin’ for, Mister Gurdy, nighttime?”

It was the sight of a stream ahead which prompted

the otter to say, “On the bank o’ yon water ’neath that willow.

That’s the spot I was aimin’ for. Would’ve been there afore, except

for yore laggin’ behind.”

It was indeed a pleasant location. They soon had a

small fire going and mint tea on the boil. From the haversack, Jum

sorted out some cheese, scones and honey. Cooling his footpaws in

the shallows, he oversaw Uggo toasting two scones with cheese on

them. “That’s the way, matey. Nice’n’brown underneath with bubbly

cheese atop. Perfect!”

The young hog did not mind preparing lunch. “I’ll

need two more scones, to spread honey on for afters.”

Uggo was surprised at how good food tasted

outdoors.

After they had eaten, Jum spread a large dockleaf

over his eyes. Lying back against the willow trunk, he settled

down.

“Let’s take a liddle nap. Ain’t nothin’ like the

sound of a gentle runnin’ stream at early noon.”

Uggo skimmed pebbles awhile, then felt bored. “I

ain’t sleepy, Mister Gurdy.”

The otter opened one eye. “Go ’way an’ don’t bother

me fer a while. Do a spot o’ fishin’ or somethin’.”

Uggo stared into the clear running stream. “But

there ain’t no fish t’be seen round here.”

The otter gave a long sigh. “Well, go downstream.

There’s a small cove where the water’s still. May’aps ye’ll find

some freshwater shrimp there, an’ we’ll make soup fer supper

t’night.”

Uggo persisted. “I’ll need a rod an’ line.”

Jum took on a threatening tone. “Ye don’t catch

watershrimp with a rod’n’line. Take one o’ them scone sacks an’

make a net. I trust yore not so dim that ye can’t make a simple

fishnet, are ye?”

Uggo stumped off, muttering, “O’ course I can make

a net. I ain’t dim, Mister Gurdy. You take yore nap. Huh, oldbeasts

need naps!”

It was lucky for him that Jum did not hear most of

what he said. Closing his eyes, he settled down with a yawn.

Finding a long twig with a forked end, the would-be

shrimpcatcher attached the ends to either side of the little cloth

sack. Making his way downstream, he watched the water intently,

feeling happy about his new purpose, still murmuring to himself.

“Just wait, Jum Gurdy. I’ll catch a whole netful o’ watershrimps.

Then I’ll creep back an’ flop them in yore lap—that’ll waken

ye!”

The cove was further than he had expected, but Uggo

finally came across it—a small inlet, patrolled by dragonflies

skimming the still, dark water. There were no shrimp to be seen,

but Uggo gave his net a speedy pull beneath the murky surface.

Pulling it out, he turned the net inside out and was rewarded by

the sight of two tiny, transparent-grey, wriggling things.

“Ahaah! There ye are, me liddle watershrimps! Any

others swimmin’ about down there? Let’s see, shall we?”

A curious wasp, investigating one of Jum Gurdy’s

eyelids, woke him. He brushed it off dozily and was about to

continue his nap when he noticed the position of the sun through

the hanging willow branches. It was past midnoon! The big otter

heaved himself upright. Had he really been asleep all that time?

Taking the pan of lukewarm mint tea from the ashes of the dead

fire, he drank it in one draught. A quick dash of streamwater

across his face brought Jum fully awake and alert.

“Where’s that liddle rascal got to? He should’ve

been back an’ waked me long since!”

Wading into the shallows, the otter cupped both

paws around his mouth, shouting aloud. “Uggo! Git back ’ere right

now! Uggo! Uggooooo!”

Raising a spray of water with his rudderlike tail,

Jum splashed back onto the bank. He stood, looking this way and

that before bellowing again.

“Uggo Wiltud, where are ye? If’n ye ain’t back by

the time I’ve counted to ten, then I’m leavin’ without ye! One . .

. two. . . . Can ye hear me, ye liddle rascal?”

He counted to ten, then repeated the performance,

with more dire threats. All to no avail. Packing everything back

into his haversack, he tried to recall his words before

napping.

“The cove downstream . . . freshwater shrimp . . .

that’s it!”

Without further ado, he scooped water over the fire

ashes and stumped off along the bank, downstream.

Every now and then, Jum paused, calling into the

surrounding woodlands. He tried to be less bad tempered, not

wanting to scare the young hedgehog away. “Uggo, come on, liddle

mate, I ain’t mad at ye. ’Twas my fault for goin’ off t’sleep like

that. Come on, show yoreself, there’s no real’arm done!”

Still travelling on and calling out, Jum came upon

the cove. There was the improvised shrimping net, floating in the

water. He pulled it out with a cold fear creeping through his

stomach. Had Uggo fallen in? Could young hedgehogs swim? Swimming

was no problem to otters, but what about hedgehogs—were they like

moles or squirrels? He had never seen any of them showing a

fondness for water. That did it. Jum Gurdy dived into the

cove.

Through his frantic underwater efforts, he stirred

the cove into a muddy area. Four times he dived, each time scouring

the cove from end to end, side to side, with no success. Regaining

his breath, the big otter swam out of the cove. He searched the

stream for a great length in either direction.

The sun was setting in crimson splendour when

Redwall’s Cellardog sat upon the streambank, weeping. Why had he

slept so long at midday? Why had he been so irate with his young

friend? He would regret it for the rest of his life. Uggo Wiltud

was gone, drowned and carried off downstream to the sea.

Shouldering his pack, Jum plodded wearily off, following the stream

out over the flatlands toward the dunes, the shore and the

sea.

It was a warm, still afternoon at the Abbey as

Friar Wopple settled herself down on the southeast corner of the

rampart walkway. She relished a quiet afternoon tea with Sister

Fisk after all the bustle and heat of the kitchens. Spreading a

cloth on the worn stones, the plump watervole laid out the contents

of her hamper. Two oatfarls filled with chopped hazelnut salad, a

latticed apple and blackberry tart, napkins and crockery.

Seeing Sister Fisk coming up the south wallsteps,

Wopple waved, hailing her friend. “Cooee, Sister!”

Redwall’s Infirmary mouse came bearing a steaming

kettle. The Friar rubbed her paws in anticipation as Fisk sat down

beside her. “I’ve set all our food out. What sort of tea are we

drinking today?”

Fisk poured out two dainty beakers of the hot amber

liquid, passing one to her companion. “Taste and guess, then tell

me if you like it.”

Blowing fragrant steam from the drink, Wopple

sipped. “Ooh, it’s absolutely delicious, Sister. I’d never guess,

so you’d best tell me.”

Fisk looked both ways, as if guarding a secret,

before whispering, “Rosehip and dandelion bud, with just a squeeze

of crushed almond blossom!”

The female Friar sipped further, closing her eyes

with ecstasy. “It’s the best you’ve ever invented, my

friend!”

Fisk took a hearty bite from her salad farl. “Not

half as good as your cooking, though. I had a bit of a rush getting

up here this noon. Had to put some salve on a bruised footpaw.

Little Alfio again!”

The Friar chuckled. “Dearie me. Sometimes I think

that poor Dibbun was born with four left paws. How many times is it

that he’s fallen and hurt himself, clumsy little shrew!”

The Sister shook her head in mock despair. “I’ve

lost count of Alfio’s tumbles.”

She settled her back up against the sun-warmed

battlements. “Ahhh, this is the life. A quiet moment of

tranquillity on a peaceful noontide, away from it all!”

Wopple set a slice of tart in front of her. “Aye,

until somebeast injures themselves again, or a whole Abbeyful of

Redwallers wants feeding!”

A thin, reedy quaver interrupted them.

“Could you feed me, please? I don’t eat

much!”

Fisk turned to Wopple. “Did you say

something?”

The Friar was already pulling herself upright.

“’Twasn’t me—sounds like somebeast outside.”

Fisk joined her as they peered over the

walltop.

Below, amidst the trees, was an old hedgehog. She

looked very thin and tottery. Leaning against an elm, she waved.

“Didn’t mean t’spoil yore tea, marms. I was just wonderin’’ow ye

gets into this fine place.”

Friar Wopple answered promptly. “Stay right there,

marm. We’ll come down and get ye!”

Opening the small east wall wickergate, they

hurried to the gable where the old hogwife had seated herself. She

began thanking them as they assisted her inside the grounds.

“May fortune smile on ye goodbeasts, an’ may yore

bowls never be empty for yore kindness t’me!”

Helping her up to the walltop, they sat her down,

placing their afternoon tea before her. She immediately fell upon

the food with gusto. Whilst she fed herself unstintingly, Friar

Wopple studied the newcomer’s face, murmuring, “Sister Fisk, who

does she put you in mind of?”

Instead of answering, Fisk turned to the old

hedgehog. “Do you have a name, marm?”

Their guest looked up from a slice of tart, smiling

to reveal only a few snaggled teeth. “Twoggs, me name’s

Twoggs.”

The Friar nodded knowingly. “And is your second

name Wiltud?”

The old hogwife finished off a beaker of tea at a

swig. “Wiltud, that’s right. . . . But ’ow did ye know?”

Friar Wopple shrugged. “Oh, I just guessed.”

Twoggs Wiltud turned her attention to Fisk’s

partially eaten salad farl. “Good guess, eh, marm? Any more o’

these nice vikkles lyin’ about?”

Wopple moved to help her upright. “Come along to my

kitchen, and I’ll see what I can find!”

Abbot Thibb joined Dorka Gurdy in the kitchens.

Both were intent on viewing the new arrival. The scrawny old

hogwife had seated herself on a heap of sacks in one corner, paying

attention only to the food she had been given.

Friar Wopple indicated her guest to Thibb and

Dorka, remarking, “Sister Fisk and I are both agreed as to who she

is.”

The Abbot needed only a brief inspection of the

snaggletoothed ancient, who was slopping down honeyed oatmeal as if

faced with a ten-season famine. He nodded decisively. “That’s a

Wiltud, without a doubt, eh, Dorka?”

The otter Gatekeeper agreed readily. “Split me

rudder, she couldn’t be ought else but a Wiltud. Ain’t shy about

table manners, is she? Lookit the way she’s wolfin’ those

vittles!”

Friar Wopple refilled the guest’s bowl with

oatmeal. Twoggs Wiltud gulped down a beaker of October Ale, nodding

to the Friar as she turned her attention back to the oatmeal.

“Thankee, marm. I likes a drop o’ ’oneyed oatmeal.

Don’t’ave enough teeth left t’deal wid more solid vikkles. I tries

me best, though.”

Sister Fisk stifled a chuckle. “I’m sure you do,

good lady. We have another member of your clan at Redwall—young

Uggo Wiltud. Though he’s off travelling at the moment.”

Twoggs licked the sides of her empty bowl, holding

it toward the Friar for another helping. “Huggo, ye say? Hmmm,

don’t know no Huggo Wiltud, but that ain’t no surprise.

Mossflower’s teemin’ wid Wiltuds. We’re wanderers an’ foragers,

y’see. Don’t suppose ye’ve got a drop o’ soup t’spare. I likes

soup, y’know.”

Friar Wopple commented, “Is there any food you

don’t like?”

Twoggs sucked at her virtually toothless gums a

moment. “Er, lemme see. May’aps oysters. I’ve ’eard tell of’em,

though I ain’t never tasted one. So I can’t tell if’n I’d like ’em

or not. Yew ever tasted an oyster, marm?”

The Abbot interrupted this somewhat pointless

chatter. “Forget oysters—but tell me, do you have a purpose in

visiting our Abbey? You’re welcome, I’m sure. However, a creature

of your long seasons, you must have passed our gates many times if

you live in Mossflower Country. So why do you suddenly turn up here

today?”

Twoggs took a sip from the bowl which the Friar had

just passed to her. She wrinkled her withered snout with delight.

“Oh, ’appy day—spring veggible soup, my fav’rite bestest thing inna

world. Fortune smile on ye, Cook marm, an’ may ye allus ’ave

someplace soft to lay yore ’ead at night!”

Taking a crust of bread, she began dipping it in

the soup and sucking noisily. Dorka smiled at the Abbot. “Don’t

look like she’s up to answerin’ any more questions as long as the

vittles keeps comin’.”

Thibb shrugged. “I think you’re right, friend.

Friar, I’ll leave her in your care. See she gets what she wants,

then let her nap in the storeroom. Mayhaps she’ll talk to me when

she feels like it. Oldbeasts like her aren’t usually in the habit

of visiting new places without a reason. Though maybe she was just

hungry.”

Sister Fisk watched as another bowl of soup

disappeared. “Aye, that’s probably it, Father. Let’s hope she soon

gets enough, before she eats us out of house and home.

Incidentally, how’s that torn pawnail of yours?”

The Abbot held it up for Fisk’s inspection. “Oh,

it’s not too bad. I’ll take more care next time I’m trying to shut

the main gates on my own.”

Dorka shook her head. “Aye, wait for me. I know

them gates—they can be tricky if ye don’t handle ’em right.”

Fisk examined the pawnail, noting that the Abbot

flinched when she touched it. “Hmm, you’d best come with me to the

Infirmary, Father. I think a little of my special salve and a

herbal binding is what’s needed to solve your problem.”

The Abbot made to walk away, excusing himself. “Oh,

it’ll be quite alright as it is. Pray don’t trouble yourself,

Sister.”

Fisk caught him firmly by his habit girdle. “It’s

no trouble at all. I won’t hurt you—now, don’t be such a Dibbun and

come with me.”

She marched him off briskly. Friar Wopple passed

Twoggs Wiltud a slice of mushroom pasty, remarking to Dorka, “I

think there’s a bit of the Dibbun in all of us when it comes to

visiting the Infirmary. One time I got a rose thorn in my footpaw

when I was a Dibbun. Old Brother Mandicus had to dig it out with a

needle. I’ve had a fear of healers ever since.”

Twoggs interrupted through a mouthful of pasty.

“Ain’t ye got nothin’ decent t’drink round ’ere?”

Friar Wopple looked slightly offended. “What d’ye

mean, somethin’ decent to drink? All the drinks are decent at

Redwall, I’ll have you know!”

The ancient hedgehog cackled. “I means summat sweet

tastin’. Alls I’ve ’ad since I came ’ere is tea an’ ale. I’m

partial t’sweet drinks, cordials’n’fizzes.”

Dorka Gurdy put on an expression of mock pity. “Oh,

ye pore ole thing, we shall have t’get ye some strawberry fizz or

dandelion an’ burdock cordial.”

Twoggs sensed that she was being mocked and replied

sharply, “Less o’ yore cheek, waterdog, or I won’t say a word about

wot I was sent ’ere t’say!”

The big otter wagged a paw at the old hedgehog.

“Who are you callin’ waterdog, pricklepig?”

Friar Wopple got between them. “Now, now—no need

for insults an’ name-calling. I’ll go and ask Foremole Roogo to

fetch a jug o’ damson an’ pear cordial from the cellars.”

Twoggs pulled herself upright, the picture of

injured dignity. “Aye, an’ I’ll come with ye. I ain’t stayin’ ’ere

t’be h’insulted by that imperdent creature!” She stalked off behind

the Friar.

Dorka humphed. “We takes ’er in, an’ that’s how we

gets treated for bein’ ’ospitable to ’er. Scrawny ole beggar. If’n

my brother Jum were ’ere, he wouldn’t let ’er near his cellars.

Huh, that ole ’og needs a good bath, if’n ye ask me!”

“Hurr, if’n Oi arsks ee wot, marm?” Foremole Roogo

entered the kitchen from the serving hatch door. Dorka explained

about Twoggs.

“One o’ that Wiltud tribe turned up at our Abbey.

She’s eaten ’er fill an’ gone down to the cellars with Friar for a

jug o’ cordial.”

Foremole jangled the ring of keys at his side.

“She’m b’aint a-gettin’ nuthen. Oi locked ee door.”

Dorka was about to reply when from the cellar

stairs there came a hubbub of crashing, shouting, squealing and

bumping. The big otter hurried off with Roogo trundling in her

wake. “Good grief, what’s all the commotion?”

They found Twoggs at the bottom of the spiral

sandstone stairs. Friar Wopple was leaning over her, trying to sit

her up against the locked door. “She pushed past me at the top of

the stairs. Tripped on those old rags she was wearin’, an’ tumbled

from top to bottom. I couldn’t stop her!”

“You’m ’old on to hurr, marms, an’ stan ee asoide!”

Foremole produced the key, opening the door. They bore Twoggs

Wiltud in between them, laying her down on a sack of straw.

Friar Wopple passed a paw in front of the old hog’s

nostrils. “Dorka, run and get Sister Fisk. I don’t know how bad she

is, but she’s still breathing. Foremole, can you find a beaker of

sweet cordial, please?”

Dorka arrived back with Sister Fisk and the Abbot

as Friar Wopple was attempting to get some of the cordial between

the patient’s closed lips. The Sister immediately took

charge.

“Give me that beaker, please. Hold her head up

gently—it looks like she’s been knocked out cold. I don’t know what

injuries she may have taken. Dorka says she tumbled the length of

the stairs, right into the locked door.”

The Friar watched anxiously as cordial dribbled

over the old hedgehog’s chin. “She just pushed past me—there wasn’t

anything I could do!”

Foremole patted the watervole’s paw. “Thurr naow,

marm. Et wurr no fault o’ your’n!”

To everybeast’s amazement, Twoggs’s eyelids

flickered open. She licked her lips feebly, croaking, “Hmm, that

tastes nice’n’sweet. Wot is it?”

Foremole wrinkled his velvety snout secretively.

“It bee’s dannelion’n’burdocky corjul, marm. Thurr’s ee gurt

barrelful of et jus’ for ee, when you’m feels betterer.”

Twoggs gave a great rasping cough. She winced and

groaned. “I ’opes I didn’t break none o’ yore fine stairs. . .

.”

Abbot Thibb knelt beside her, wiping her chin with

his kerchief. “Don’t try to speak, marm. Just lie still now.” He

cast a sideways glance at Sister Fisk, who merely shook her head

sadly, meaning there was nothing to be done for the old one.

Twoggs clutched the Abbot’s sleeve, drawing him

close. The onlookers watched as she whispered haltingly into

Thibb’s ear, pausing and nodding slightly. Then Twoggs Wiltud

extended one scrawny paw as if pointing outside the Abbey. Abbot

Thibb still had his ear to her lips when she emitted one last sigh,

the final breath leaving her wounded body.

Friar Wopple laid her head down slowly. “She’s

gone, poor thing!”

Thibb spread his kerchief over Twoggs Wiltud’s

face. “I wish she’d lived to tell me more.”

Sister Fisk looked mystified. “Why? What did she

say?”

The Father Abbot of Redwall closed his eyes,

remembering the message which had brought the old hedgehog to his

Abbey. “This is it, word for word, it’s something we can’t

ignore.

“Redwall has once been cautioned,

heed now what I must say,

that sail bearing eyes and a trident,

Will surely come your way.

Then if ye will not trust the word,

of a Wiltud and her kin,

believe the mouse with the shining sword,

for I was warned by him!”

heed now what I must say,

that sail bearing eyes and a trident,

Will surely come your way.

Then if ye will not trust the word,

of a Wiltud and her kin,

believe the mouse with the shining sword,

for I was warned by him!”

In the uneasy silence which followed the

pronouncement, Dorka Gurdy murmured, “That was Uggo Wiltud’s dream,

the sail with the eyes and the trident, the sign of the Wearat. But

my brother Jum said that he’d been defeated and slain by the sea

otters.”

Abbot Thibb folded both paws into his wide habit

sleeves. “I know, but we’re waiting on Jum to return and confirm

what he was told. I think it will be bad news, because I believe

what old Twoggs Wiltud said. The mouse with the shining sword sent

her to Redwall, and who would doubt the spirit of Martin the

Warrior?”