5

As dawn’s rosy paws stole over the Abbey walls,

Jum Gurdy was getting ready to leave for the coast, intent on

questioning his old uncle Wullow. The sturdy otter chuckled as he

watched Friar Wopple packing rations into his haversack.

“Go easy, marm. I ain’t plannin’ on bein’ gone for

ten seasons. That’s enough vittles t’keep a regiment o’

Salamandastron hares goin’.”

The kind watervole waved a package of candied

chestnuts at the Cellardog. “Be off with ye, Jum Gurdy. I’ll not

see any Redwaller starve on a journey. Besides, y’might like to

give some o’ these vittles to yore ole uncle Wullow.”

Jum smiled as he slipped a flask in with the food.

“Aye, thankee. Ole Wullow’d like that, marm. I’m takin’ ’im some o’

my best beetroot port as a gift.”

Young Uggo Wiltud, who had got over his ill stomach

and was now sentenced to three days’ pot washing, looked over from

his greasy chore. The gluttonous hedgehog was always interested in

the subject of food or drink.

“I’ve never tasted beetroot port, Mister Gurdy.

Wot’s it like?”

Jum shouldered his loaded haversack, commenting,

“Never mind ’ow it tastes, young Wiltud. You just get on with yore

pot scourin’!”

Scowling, Friar Wopple picked up one of the pots.

“The whole Abbey’d be down with tummy trouble if they had to eat

vittles cooked in this—it’s filthy! Do it again, Uggo, an’ make

sure ye scrub under the rim!” She turned to Jum with a

long-suffering sigh. “I’ve never seen a young ’og so dozy in all my

seasons!”

Uggo’s voice echoed hollowly as he poked his head

into the pot. “I can’t ’elp it if’n I ain’t a champeen pot

washer!”

The Friar waved a short wooden oven paddle at him.

“Any more of those smart remarks an’ I’ll make yore tail smart with

this paddle. Stealin’ hefty fruitcake is about all yore good at, ye

young rip!”

Still with his head in the pot, Uggo began weeping.

“I said I was sorry an’ wouldn’t steal no more cakes. But nobeast’s

got a good word for me. I’m doin’ me best, marm, but I just ain’t a

pot washer.”

Jum Gurdy suddenly felt sorry for Uggo. There he

was, clad in an overlong apron, standing atop a stool at the sink,

with grease and supper remains sticking to his spines. The big

Cellardog lifted him easily to the floor. “Smack me rudder, matey.

Yore a sorry sight, an’ that’s for sure. Stop that blubberin’, now.

You ain’t been a Dibbun, not for three seasons now. So, tell me,

wot are ye good at, an’ don’t say eatin’ cake!”

Uggo, managing to stem his tears, stood staring at

the floorstones, as if seeking inspiration there.

“Dunno wot I’m good at, Mister Gurdy.”

Jum hitched up the haversack, winking at Friar

Wopple. “I think I know wot we should do to this scallywag,

marm.”

The Friar leaned on her oven paddle, winking back.

“Oh, an’ wot d’ye think you’d like t’do to Master Wiltud? Fling him

in the pond, maybe?”

Uggo flinched as Jum took off the long apron. The

otter walked around him, looking him up and down critically. “Hmm,

he don’t look like a very fit beast t’me, Friar. Bit pale an’

pudgy, prob’ly never takes any exercise, eats too much an’ sleeps

most o’ the day. I think a good long walk, say a journey to the

sea. That might knock ’im back into shape. Wot d’ye think, Friar

marm?” Wopple agreed promptly. “Aye, it might do our Uggo the world

o’ good, sleepin’ outdoors, marchin’ hard all day, puttin’ up with

the bad weather an’ not eating too much. I think y’might have

somethin’ there, Jum!”

Uggo’s lip began to tremble as he looked from one

to the other. “Marchin’ all day, sleepin’ out in the open, gettin’

wet’n’cold in the wind an’ rain. Wot, me, Mister Gurdy?”

Jum shrugged. “As y’please, mate. There’s always

more pots t’wash an’ floors to scrub, I shouldn’t wonder, eh,

marm?”

Friar Wopple narrowed her eyes, glaring at Uggo.

“Oh, yes—an’ ovens to clean out, veggibles to peel an’ scrape, the

storeroom to sweep out . . .”

Jum Gurdy began trudging from the kitchens, calling

back, “Ah, well, I’ll leave ye to it, Uggo mate. ’Ave fun!”

The young hedgehog scrambled after him, pleading,

“No, no, I’ll go with ye, Mister Gurdy. Take me along,

please!”

Hiding an amused grin, Friar Wopple waved a

dismissive paw. “Take him away, Jum. The rascal’s neither use nor

ornament around here. Go on, young Wiltud—away with ye!”

She followed them to the kitchen door as Jum strode

off, commenting blithely, “Well, come on then, young sir, but ye’d

best keep up, or I’ll ’ave to tie ye to a tree an’ pick ye up on

the way back. Come on, bucko. Move lively, now!”

Uggo scurried in the big otter’s wake. “I’m goin’

as fast as I can, Mister Gurdy. You wouldn’t leave me tied to a

tree, really, would you . . . would you?”

Abbot Thibb saw the pair walking across Great Hall

as he entered the kitchens. He picked up a fresh-baked scone,

spread it with honey and took a bite.

“Good morning, Friar. What’s going on with those

two?”

The Friar poured cups of hot mint tea for them

both. “Oh nothin’, really. I suspect that Jum’s givin’ young Uggo a

lesson in growing up usefully. A trek to the seacoast with our

Cellardog behind him may do that hog a power o’ good,

Father.”

Thibb blew on his tea and sipped it carefully.

“Right, marm. I think Jum Gurdy’s just the beast to teach that

scamp a lesson or two.”

In the belltower, Matthias and Methusaleh,

Redwall’s twin bells, boomed out into the clear spring morn,

signalling breakfast at the Abbey.

Outside on the path, Uggo called out hopefully,

“May’aps we’d best go back for our brekkist, Mister Gurdy?”

Jum Gurdy shook his head, pointing the way.

“Already’ad brekkist whilst you was still snoozin’. Keep goin’,

young un. ’Tis quite a way ’til lunch!”

By midday, Greenshroud was well out to sea.

Razzid Wearat took a leisurely meal of grilled seabird, washed down

with a beaker of seaweed grog. He watched a wobbly-legged old

searat clearing the remains away, then rose from the table. He

snapped out a single word.

“Cloak!”

The rat dropped what he was doing to get the green

cloak, holding it as Razzid shrugged his shoulders into it.

“Trident!”

The serving rat placed the trident in his waiting

paw. Without another word, the Wearat waited on his minion to open

the cabin door, then strode out on deck. A corsair searat was at

the tiller.

Razzid wiped moisture from his weepy eye. “What’s

the course?”

The corsair replied smartly, “As ye ordered, Cap’n,

due east!”

Vermin were loitering near, coiling ropes and doing

other needless tasks, listening alertly for the Wearat’s command as

to where they would be sailing.

He did not keep them waiting, calling out loud and

clear, “Take ’er in closer to shore! Lookout, keep watch for

anythin’ interesting onshore!”

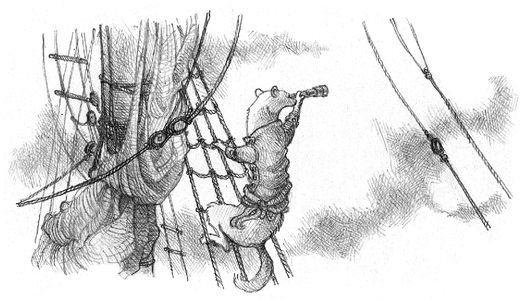

A sharp-eyed young ferret tugged his ear in

acknowledgement. “Aye aye, Cap’n!” He began climbing into the

rigging.

Razzid’s next words came at the crew like a

thunderbolt.

“Stay close to the shore, but set a course for the

High North Coast!”

The word had been given. Razzid Wearat was bent on

a return battle with the sea otters. An ominous silence fell over

the crew. Those who had lived through the last disastrous foray

knew the strength and bloodlust of Skor Axehound’s warriors. None

of the vermin had thought that Razzid would be foolhardy enough to

try a second attack. However, none of the corsairs was so rash as

to dispute their captain’s decision. They returned to their tasks

in sullen silence—all but one.

A muscular, tattooed ferret, who had barely escaped

with his life at the first incident, was heard to mutter to the rat

he was working alongside, “Huh, those wavedogs beat the livin’ tar

out of us. They ain’t beasts t’be messed about wid.”

He turned and found himself facing Razzid.

“Ye were sayin’?”

The ferret backed off nervously. “Never said

nothin’, Cap’n.”

Like a flash the trident was a hairsbreadth from

his neck. The Wearat sounded dangerously calm. “Lie to me an’ I’ll

slay ye here an’ now. What did ye say? Tell me.”

The ferret was a seasoned killer and no mean

fighter, but he quailed under the Wearat’s piercing eye.

“I jus’ said those wavedogs wasn’t beasts t’be

messed wid.” Razzid let the trident barbs drop.

“So, that’s what ye think, eh? Anyone else think

that?”

The ferret looked nervously at his mates’ faces,

but nobeast was about to speak out. He smiled weakly and shrugged.

“I didn’t mean nothin’, Cap’n. On me oath, I didn’t!”

Razzid stared levelly at him, still calm. “Ah, but

I heard you, my friend. What was it? ‘Those wavedogs beat the

livin’ tar out of us . . .’?” He paused to wipe dampness from his

bad eye. As he spoke again, his voice rose to a shout and his face

became contorted with rage.

“Beat the living tar out of us? Nobeast has ever

done that to Razzid Wearat and lived to tell of it. My wounds came

from saving this ship—aye, and all the idiots I called a crew. You

were one of them. I saved you all. And you dare to say that some

foebeast beat me!”

Before the tattooed ferret could reply, Razzid

lunged with his trident. Pierced through the stomach, the ferret

shrieked. Like a farmer lifting hay with a pitchfork, the Wearat

heaved his victim up bodily on the trident and hurled him

overboard.

The crew stood shocked by the swift, vicious

act.

Laughing madly, Razzid leaned over the stern

gallery, bellowing at the dying corsair, “When ye get to Hellgates,

tell ’em it was me that sent ye—me, Razzid Wearat!”

He turned to the crew, wielding his dripping

trident. “Avast, who’s next, eh? Any of you bold bullies wants to

argue with me, come on, speak out!”

The silence was total. Rigging creaked, sails

billowed, waves washed the sides of Greenshroud, but not a

single corsair spoke.

Razzid laughed harshly. “The High North Coast,

that’s where this ship’s bound. But this time we won’t be ambushed

up to our waists in the sea. Now I know wot my vessel can do, it’ll

be me dishin’ out the surprises. We’ll give those wavedogs the same

as the rabbets got at the badger mountain.”

Shekra the vixen called out. “Aye, the waves’ll run

red with the blood of our foebeasts. Our cap’n’s name will become a

legend o’ fear!”

Mowlag and Jiboree took up the cry, until all the

crew were bellowing, “Wearat! Wearat! Razzid Wearat!”

Exulting in the moment, Razzid chanted with

them.

Suddenly he slashed the air with his trident,

silencing the noise. His anger quelled, he spoke normally again. “I

am the Wearat. I cannot die—you’ve all seen this. Fools like that

one, and that one, would not heed me.” He gestured overboard to

where the ferret was floating facedown in Greenshroud’s

wake, then up to where the head of Braggio Ironhook was spiked atop

the foremast. Razzid chuckled. “But believe me, there’ll be no

mistakes this time. The beast ain’t been born who can get the

better o’ me, or my ship, or my crew. Right, mates?”

This triggered another wave of cheering.

Razzid beckoned to a small, fat stoat. “I remember

you. Yore Crumdun, Braggio’s little mate.”

Crumdun saluted hastily, several times. “Er, aye,

Cap’n, but I’m with yew now. On me oath, I am!” The Wearat winked

his good eye at Crumdun.

“Go an’ broach a barrel o’ grog. Let my crew drink

to a winnin’ voyage. Make that two barrels.”

As they sailed north, the corsairs drank greedily

from both barrels, one of which was named Strong Addersting and the

other Olde Lobsterclaw. The vermin swilled grog, grinning foolishly

at the slightest thing.

Jiboree rapped Crumdun’s tail with the flat of his

cutlass. “Ahoy, wasn’t you a pal o’ Iron’ook?”

Crumdun giggled nervously. “Heehee . . . I was, but

I ain’t no more.”

Jiboree leered at him, then waved his cutlass

blade. “I’eard that none o’ Iron’ook’s mates could sing. So, if’n

yew wasn’t a proper mate of ’is, then ye must be a good ole singer.

Go on, lardtub, give us a song!”

With Mowlag’s dagger point tickling him, the fat

stoat was forced to dance a hobjig whilst warbling squeakily.

“Ho, wot a drunken ship this is,

’tis called the Tipsy Dog,

an’ the bosun’s wife is pickled for life,

in a bucket o’ seaweed grog!

’tis called the Tipsy Dog,

an’ the bosun’s wife is pickled for life,

in a bucket o’ seaweed grog!

“Sing rum-toodle-oo, rum-toodle-’ey,

an’ splice the mainbrace, matey,

roll out the grog, ye greedy hog,

’cos I ain’t had none lately.

an’ splice the mainbrace, matey,

roll out the grog, ye greedy hog,

’cos I ain’t had none lately.

“Our cap’n was a rare ole cove,

’is name was Dandy Kipper.

He went to sea, so he told me,

in a leaky bedroom slipper!

’is name was Dandy Kipper.

He went to sea, so he told me,

in a leaky bedroom slipper!

“Sing rum-toodle-oo, rum-toodle-’ey,

this drink is awful stuff,

me stummick’s off, an’ I can’t scoff,

this bowl o’ skilly’n’duff!

this drink is awful stuff,

me stummick’s off, an’ I can’t scoff,

this bowl o’ skilly’n’duff!

“The wind came fast an’ broke the mast,

an’ the crew for no good reason,

dived straight into a barrel o’ grog,

an’ stayed there ’til next season!”

an’ the crew for no good reason,

dived straight into a barrel o’ grog,

an’ stayed there ’til next season!”

Night had fallen over the vast seas. The water was

relatively calm, though a faint west breeze was drifting

Greenshroud idly in toward the shore. Both grog barrels had

been liberally punished by the vermin crew, most of whom were

slumped around the deck. The tillerbeast was snoring, draped over

the timber arm. He never stirred as the ship nosed lightly in, to

bump softly into the shallows.

Only one crew member was wakened by the gentle

collision of vessel and firm ground—the sharp-eyed young ferret

lookout. It was his first encounter with the heady grog, so he had

fallen asleep in the rigging. Fortunately he was low down and not

up at the masthead. The light landing dislodged him from his perch.

He fell into the shallows, waking instantly on contact with cold

salt water. Shaking with shock, he clambered back aboard, his mind

racing. Who would get the blame for allowing the vessel to beach

itself? Would he be blamed?

Almost all the crew were in a drunken sleep. The

ferret took a swift look overboard; it was low tide. How long would

it take for Greenshroud to float off on the turn? Off to his

right, he saw something. It was a small dwindling fire above the

tideline. The lookout saw it as a chance to concoct a feasible

excuse should the ship not float off before Razzid Wearat wakened

himself. He slipped back ashore and crept stealthily toward the

fire.

The young ferret had exceptional eyesight. Long

before he reached the fire, he could see what was around it. A

tumbledown lean-to, fashioned from an old coracle, with a big, fat,

old bewhiskered otter sitting outside. The otter, wrapped in a

sailcloth cloak, had his head bowed. He was obviously fast asleep

in front of the glowing embers.

As the ferret hurried back to the ship, he saw a

furtive figure jump overboard and scurry off eastward. Telling

himself it was no business of his, he climbed aboard and gently

wakened the searat who was slumped across the tiller. They held a

swift whispered conversation, then the searat went off and roused

Mowlag.

“I saw a firelight on the shore, mate, so I took

the ship in to get a sight of it. The lookout saw there was an

otter asleep by it. Big ole beast, ’e was. Wot d’ye think we should

do?”

Mowlag tottered upright, still staggering from the

grog he had downed. Patting the searat’s back, he nodded at the

lookout. “A waterdog, eh? Ye did well. I’ll go an’ tell the cap’n.

There’s nobeast ’e hates more’n those waterdogs. Yew stay put. Keep

an eye on the waterdog in case’e moves.”

Nothing could have pleased the Wearat more than the

opportunity to revenge himself on his enemy. He stole silently from

the prow of Greenshroud, carrying his trident. Mowlag,

Jiboree, the lookout and the steersrat flanked him.

“Wot d’ye think the cap’n will do to that beast?”

the young ferret lookout whispered to Jiboree.

The weasel grinned wickedly in anticipation. “Yew

just watch. Cap’n Razzid don’t like waterdogs. I wager ’e slays’im

good’n’slow, bit by bit!”

Jum Curdy’s uncle Wullow snuffled a little. His

head drooped further onto his chest, then he carried on snoring,

stirring his whiskers with each breath. The coracle lean-to was

sheltering his back, the fire embers were warming his front, and

the tatty sailcloth cloak was keeping vagrant breezes at bay. A

bundle of dead twigs and dried reed landed on the little fire,

causing it to flare up. A spark stung Wullow’s nosetip. He woke to

find himself facing a strange, brutal-featured beast and four

vermin corsairs. The flickering firelight reflected the evil

glitter in the Wearat’s one good eye.

“We wouldn’t want yore fire goin’ out on ye,

friend. We’ll make things nice an’ warm for ye—won’t we,

mates?”

The other four vermin sniggered nastily. Wullow

gave a deep sigh of despair as they closed in on him.