CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Iwo Jima

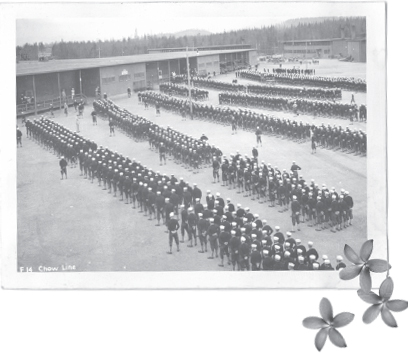

A mob of new guys came in last night and chow line is about a mile long.—March 6, 1945

As the weeks went by, I often gave my father updates on my progress with the letters by telling him the date on the most recent letter and a few details about its contents. But a few months had passed since we’d talked about them in depth or I had asked him any questions.

My mother and I now checked in with each other regularly. She would let me know if Dad was having nightmares, or if she’d noticed his mood change. Likewise, I would share if we’d been talking about something that seemed to upset him. Sometimes there seemed to be a direct correlation. Other times, I couldn’t see a link at all.

So when I would update him about the letters, I was careful not to include anything that might trigger nightmares for him. The problem with our system was that I didn’t always know what the trigger was. Something that seemed benign could be something that wasn’t at all benign. I was very careful with what I talked to him about.

But one Wednesday, as soon as we’d ordered our usual breakfast, he caught me off guard by asking me a question.

“So, how are the letters coming?” he asked.

For some reason, I didn’t even think to filter things like I usually did. Maybe it was because it was he who asked the question, instead of me offering. Maybe I was just tired—maybe we both were. Whatever the case, the words Iwo Jima came tumbling out of my mouth.

“The letters I’m transcribing right now were probably written at about the time you went to Iwo Jima,” I said.

As I had researched Iwo Jima, I had learned what a huge part of WWII it was. It made me wonder if Dad’s military records might hold some information that might be helpful. Maybe they would offer information that would lead me more quickly and efficiently to something of benefit to my dad. Or maybe I was spinning my wheels and trudging through all of this and I didn’t need to.

“Dad, have you ever thought about sending for your military records?” I asked.

“No,” he said. “There wouldn’t be anything in them.”

“You never know,” I said.

“You don’t understand.”

He hesitated, looking out the window at the morning traffic, which in Walla Walla meant a line of three or four cars in succession. His eyes scanned the horizon. He pulled a handkerchief from his pants pocket and slowly cleaned his glasses. He put them back on and again looked out the window.

“In one of those instructional sessions on Oahu, we were told we’d be traveling with no orders. See, usually whenever you went out to sea, you went with a manila envelope which had your orders in it. That’s how they kept track of who was sent where and what they did. But when our group was put aboard that amphibious plane at Ford Island, there were no such orders. So I know there aren’t any records of what I did.”

He looked down at his hands.

“It’s like I was never there,” he added.

I didn’t know what to say. Of course he was there. I knew the kind of mind he had. I knew he couldn’t have made this up or been mistaken. Still, a lack of firm acknowledgment seemed to be eating away at him.

“Anyway,” he said interrupting my thoughts. “We were transferred at sea to a submarine. We never saw a name or number but were told it would be the Sailfish. That particular submarine had become famous because it was originally the Squalus which was re-commissioned the Sailfish after a terrible accident at sea. I looked it up the other day on the Internet. It’s amazing the information you can get now. I looked up all of the patrols. And there weren’t any that went to Iwo Jima. So I just don’t know. All this makes me feel like I must be crazy or something. All these years, I believed I was on the Sailfish. And it turns out I wasn’t. Maybe they just told us that. Or maybe I imagined it all.”

He squinted as he looked out the window again.

“Dad,” I said. “You didn’t imagine it. There has to be documentation of what you did. I think you should send for your records. So tell me…” I said, changing the subject slightly. This time I knew exactly what I was doing. Months ago, he’d left off with he and his comrades boarding a ship in the middle of the ocean. If he was having nightmares recently, my mother hadn’t noticed them. And his emotions had returned to an even kilter. And since he seemed open today in a way I hadn’t seen in a while, I decided to push forward.

“What was it like once you got on the submarine at Iwo Jima?”

He didn’t hesitate in answering. In fact, when he began speaking, he seemed to gain resolve to remember what he had to tell me. When he started to talk, I could hear determination in his voice. He wanted to remember. He wanted to share.

“Well,” he said, “I can’t exactly remember when we boarded but it was before the initial invasion on February 19. Our sub sat on the bottom of the ocean and shot up an antenna that was attached to the top of the sub. We called it ‘the football’ because it was shaped like one. It was a top-secret thing at the time. See, usually you had to surface to receive messages but with this thing, most of it stayed below the water. The only part that was above water was an antenna, which of course couldn’t be seen by the enemy. If you just picture this vast ocean with a little antenna, you can see why. Anyway, we just sat there copying code day and night. The code could only be copied a short distance, or line of sight. But if you were on a high point or across an uninterrupted surface, that could be extended a couple hundred miles. I suspect we were copying stuff from Chichi-Jima, but I don’t really know.”

“Did you ever decode things that were really critical?” I asked.

“No. Probably not,” he said. “I saw a lot of the decoded messages and they related to supplies and personnel being moved by the Japanese. We just never knew what was important and what wasn’t. We just passed the messages on to the cryptanalysts and they figured it all out. But I did get to where I could read what I was copying. And sometimes I read it but mostly there just wasn’t time. And we did surface a bit too. The one I remember most vividly was when we surfaced and I could hear cheering. I made my way to the deck of the sub and off to my right I could see the American flag. It was erected on Mount Suribachi. It was quite a sight but, of course, we didn’t know how famous that moment would be.”

“So you were there when the flag was erected?” I asked, shocked. “That’s amazing, Dad!”

“Yeah, I was thinking about it the other day and wondering if I’d seen the first or second flag. You know, they put up the first one and then replaced it with a bigger one a while later,” he said.

“Yeah, I remember reading about that,” I replied.

“I must have seen the second one,” he said. “We were quite a ways out there, so there’s no way we would have seen the smaller one. Anyway, a few days after the initial invasion, we were flown back to the base. When we left Oahu, it was virtually deserted. But when we returned, the men were coming back in large groups.”

So he had been there! It slipped out so easily, so quickly. He didn’t even seem to know that he’d told me something I hadn’t known before.

My father had been in the war, despite all the times he’d said he hadn’t. The stories he’d told when I was a little girl were a very small and very censored part of his experience during WWII. He’d been on a submarine during one of the most important battles of the war.

I tried to fathom what he’d just revealed. The ripples of this one revelation reached so far that I couldn’t even think about it all at once. He’d been copying a top-secret Japanese code—at the bottom of the ocean. My father was more than just a sailor who’d sat behind a desk during the war. He and his team had played a very important part in it. My mind spun with the possibilities of what might have happened to him. He’d kept this information hidden for so long. Why? And if he’d successfully kept this a secret for more than fifty years, what more might there be?

My father seemed content with the story he’d shared, oblivious to the fact that it had opened up a ton of new questions for me. He took another sip of his water, and then slid across the booth to leave. He handed me the check and a $20 bill.

“I’ll meet you at the car,” he said.

As I pulled into his driveway, I tried one more time.

“Dad,” I said. “You have to send for your records.”

This time he didn’t argue.

March 6, 1945

Dear Folks,

It’s not mail time yet so no new mail since yesterday.

A mob of new guys came in last night and chow line is about a mile long. Also the show is packed so I’ll have to get there early.

Had to be a messenger for three hours one afternoon a couple of days ago. That’s the only work I’ve done so far. And didn’t do a thing then except wait for something to turn up. Just before quitting, one of the officers sent me for his hat—such a war. Rest of time I read a railroad magazine and studied for my course.

After watching that marimba player Sunday, I’ve about decided that’s for me. They are a little hard to put in your pocket tho.

You know I’m sure glad I don’t get letters like most of the guys do. I’ve seen a lot of them off and on. Jonesy’s wife is always way down in the dumps and the letters are so sad that it almost even makes me want to cry too. Don’t see how he could stand them. Guess they are better than nothing tho and maybe he even enjoyed them. Think I got the best assortment of mail of any one in the Navy.

All the immediate family—you, Ray & Iris always give me the latest good or bad—in such a way that it’s always fun to read ’em over and over. And you should see Kenny & Lois’s. She writes one paragraph & he the next always arguing. I really get a kick out of them instead of missing everyone so much. Don’t believe I have anyone that writes sad or dry letters. That’s sure something I can be thankful for.

By some freak of radio waves—I can pick up Honolulu main police station on one end of band on my radio. When nothing interesting is on the two stations I just tune it over there and get the latest on stolen cars and bad men in general.

Well, nothing to answer so guess I’ll close.

Write. Love, Murray

Two weeks after the most harrowing and exciting experience of his life, my father’s letters revealed nothing. I was still looking for something, anything, that he’d snuck past censors to confirm what he was now remembering. But there was nothing—not one word.