CHAPTER FIVE

Tell Me a Word

I’m trying to get up nerve enough to try a surfboard. I’ll let you know how I make out.—February 9, 1945

“You’re going to do what?” my husband asked.

“Transcribe the letters,” I said.

“You’re going to type them all?”

“Well…yes,” I replied.

“Why?” he asked. But he continued without letting me answer. “Karen, do you realize how much time that would take? We’re already too busy and now you want to add something like this?”

“You’ve seen the letters,” I said. “Dad’s handwriting is hard to read. It’s tiny and runs together. And the paper used back then is so thin and fragile.”

But I knew he was right. My life was full and I was already chronically tired. I worked part time teaching children with disabilities at the local elementary school. In the afternoons, cooking, cleaning, shopping, and other chores filled my time. After school and evenings were spent chauffeuring the kids from one activity to another: soccer practice, music lessons, and school events. Somewhere amidst our tight schedule, we managed to eat dinner and supervise homework. Then it was bath time, story time, and bedtime. And the next morning the organized chaos began all over again.

Yet I couldn’t shake the feeling that it needed to be done.

“I just want the kids to each have their own copy of my dad’s letters,” I said, trying to come up with an answer for what even I didn’t understand.

“Then go down to Staples and make copies,” he said.

That certainly made sense. But, I thought, maybe this wasn’t about what makes sense. This was something that just felt right to me. There weren’t any words to explain it, especially to my practical husband. So I gave up trying and decided to find my own time to work on them.

Each night after everyone was in bed, I sat alone with the letters, typing them into my word processor. When there was something I didn’t understand, I wrote myself a note on whatever was handy—a scrap of paper, the back of an envelope, a receipt from the grocery store. A few weeks passed before I came up with a better way to keep track of my questions: simply setting the font to bold and writing the questions right into the text.

I stopped by my parents’ house after work one day. Walking up the brick steps, I used the secret knock my father taught me when I was still in pigtails: four knocks, then a pause, and then two knocks.

It had always been our secret knock, but I’d only recently learned what it meant. My husband and I had just bought a fixer-upper near my parents’ house, so Dad began visiting more often. He enjoyed riding over on his Segway, a stand-up scooter, to visit with his grandchildren or help with our latest home-improvement project. Each visit started with the same knock. So one day I asked him about it.

“Dad,” I said, “as long as I can remember, we’ve used the same knock.”

“Well, you know what it means, don’t you?” he asked.

I shook my head.

“It’s Morse code,” he said.

“One, two, three, four…one, two,” he said. “H…I.” His fingers quickly tapped the air as he spoke. “It means ‘hi’ in Morse.”

“I didn’t know that,” I said. “All this time, I just thought it was our secret knock.”

He laughed.

With that fresh memory swirling in my mind, I let myself in my parents’ house with a small smile on my face. I found my father sitting in his favorite recliner, watching TV.

“Hi, Dad,” I said.

“Hi, yourself,” he answered.

He searched the cluttered table next to him. Under magazines, books, and mail, he found the remote control and pressed mute. We talked for a few minutes about the weather and the book he was reading. I wanted to bring up the letters, but I didn’t know how. Phone calls and visits to my parents’ house usually consisted of a little small talk with Dad quickly followed by me asking for my mom. I was suddenly acutely aware that I really didn’t talk to my dad all that much. I wanted to say, “Dad, tell me about the war.” But the words hid.

“I’ve been reading your letters,” I started.

“You have?” he asked.

“Yeah. They’re pretty interesting,” I said.

“Well I didn’t think anyone would want to read those old things.”

There was a barely noticeable lilt to his voice. Encouraged, I continued. “So when did Grandma give them to you?” I asked clumsily.

“I don’t remember,” he said. “Maybe a few years after I got home. I don’t know.”

“Did you know she had them before that? I mean did you know she saved them?” I asked.

“No,” he replied. “I don’t know. I just don’t remember.” There was frustration in his voice. “I just can’t help you with this stuff. I don’t remember anything. It was too long ago.”

For most people his age, maybe this would be true. Fifty years is a long time to remember such details. But not for my father, who’d always had a meticulous memory. I knew better than that. Still, he’d given me the letters and even seemed pleased I was reading them.

He un-muted the television before I could ask another question. “This channel has some good old movies. This one is about…”

He went on to tell me all about the movie. I watched the screen as if I were muted. I tried to concentrate on it, to come up with a question to ask just to show an interest. But all I could think was, “How am I ever going to get him to talk to me?”

I’d come over hoping to have a conversation with him. I wanted to sit down and just talk, casually like I did with my girlfriends. I wanted to know what he thought and how he felt.

When I was growing up and even into adulthood, I had always talked to my dad and he had talked to me, but we never really had a conversation. And now, after almost forty years, we didn’t know how to talk to each other. We only knew how to talk at each other. We knew how to wait politely for the other to finish talking. Eye contact was sparse and infrequent—we looked down, or around, or out the window.

We’d communicated this way all of my life. And now, when it mattered, it seemed too late to learn a new way.

I waited for a commercial. He always muted the sound on commercials. But this time he didn’t. I watched more of the movie and another set of commercials. My father had been hard of hearing all of my life, so when the television volume was on, it was impossible to hold a conversation. He kept the sound on through another set of commercials.

He had no intention of talking to me.

Feb 9, 1945

Dear Folks,

I didn’t have room in last letter to answer all your questions. No letters today so may get caught up.

We just about bought a radio a little while ago. They are hard to get and easy to get rid of. Someone beat us to it tho. You can always get rid of them in 5 minutes by putting up a notice on the bulletin board. And you don’t need to take a loss either.

We have all the main radio programs and have a lot of military band and Hawaiian music instead of the soap operas in the states.

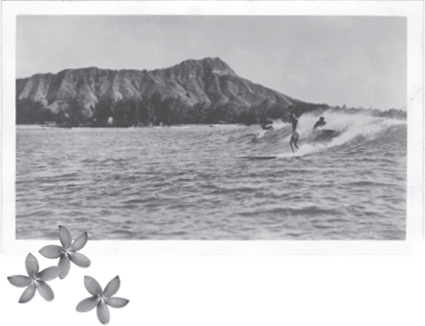

I’m trying to get up nerve enough to try a surfboard. I’ll let you know how I make out. It looks easy but they say it’s tricky.

Oh yes, Dad, they have Fiats and Cords here. I’ve seen two Cords and one Fiat. There are all makes and models of cars here. About the only difference is that the majority of them have all leather upholstery. Don’t know just why.

When we went to see “The Mikado” last night, we went through the best part of town. I’d never been there before. Very nice houses and a Sears store is located way out on the edge of town. It’s a super-modern, one-story building as are most of the large stores in town. We saw the university campus too. It was really nice—lots of grass, which was something neat to see. Camp is all just dirt and tents.

Well, guess you know by now what my deal is here. Waiting for glasses now. The doc seemed quite upset about my eyes so maybe something cooking. If so, I would probably get a restricted or limited service rating and be assigned to a shore base. Otherwise could be on ship or an advanced base. Will be a while yet before anything happens tho.

The place is about deserted now. You’ll just have to guess why and read the papers.

Days are sure long—you’d probably all like to trade with me. Get up around 715, eat breakfast 730 just across the street. Muster at 750. Then nothing until noon. Eat around noon or one and nothing until 530 p.m. Have supper then. Go to a show at seven and back at nine or so—lights out at ten. Mail call at noon and five p.m.

A very invigorating existence. Spend rest of time browsing around ships service, drinking Nesbit orange pop, visiting tent library and reading and writing letters. I may have to resort to building model airplanes soon.

Better get a letter off to Iris. Think I’ve written an average of almost three a day in past month. I’ve been on the island just a month now. Write. Love, Murray

As I read through more of his letters, I realized I was looking for something, a clue perhaps. But a clue to what? A clue to why he’d kept the letters a secret? That was part of it. But there was more. I had the unmistakable feeling that I’d missed something. When I read the line in his letter that said, “The place is deserted now. You’ll just have to guess why and read the papers,” something quickened in me. And something else bothered me.

Dad has a favorite game that says a lot about his memory for detail. He likes to challenge me, “Say a word, any word, and I’ll tell you a story about it.” Then I say some random word like, “horse” or “red” or “sidewalk.” He thinks for just a moment and then recalls some story, some obscure parable from his past. He recalls details that anyone else would never have committed to memory in the first place. So why couldn’t he answer any of the questions I asked him?

It didn’t fit with what I knew about him. He could read a complicated, technical book and then use the information years later, from memory, to design or fix something. Our family had long thought he had a photographic memory, though he was adamant that he didn’t.

Then I remembered something important: his memory for detail was never more obvious than when he wrote an email.

My father had been online since the Internet first came to town. In fact, he is proud to share that he was one of the first in Walla Walla to have it. When I finally jumped on the Internet bandwagon, I realized what a prolific writer he was. The whole family gives him a hard time about his extremely long emails. “Ask me what time it is,” he jokes, “and I’ll tell you how to build a watch.” And it’s true. If I emailed, casually asking how lunch was, he’d reply with every detail: who he went with, where they ate, what they ate, how it tasted, and what the conversation entailed.

It was this attention to detail that gave me an idea: perhaps if I put my questions to him in an email, he would answer me, without the awkwardness we both seemed to feel when we talked in person.

Though I tried to save working on the letters for nighttime, I couldn’t wait to try this. After supper, I propped my laptop on my knees, opened to the letters I’d typed so far. I minimized the page to half the size of the screen and then opened my email and transferred the bolded questions. I numbered each one and left space for him to answer. I hit send and butterflies invaded my stomach.

I wondered if he’d even respond. My predictable father had become unpredictable to me. He’d never failed to answer an email promptly in the past. But after my failure to get him to answer the simplest of questions, I wasn’t sure of anything anymore. I’d just have to wait and see.

The next day, I received a three-page response. He answered each question in the blank space I had left. And just as I’d predicted, he answered in detail.

The first question was about his glasses.

“In your letters, you always seem to be getting your glasses fixed. Could you tell me about your glasses?”

He told the story, starting when he was a little boy.

Dad was eight years old when, one day, as he was walking with his dad, he commented on the two cows in the pasture.

“Two cows?” My grandpa laughed.

Dad repeated his observation.

“There aren’t two cows,” Grandpa said. “There is only one.”

That is how my father found out that it wasn’t normal to see everything in duplicate. From then on he wore thick glasses, and unlike others his age, he was happy to wear them.

The glasses issued to him by the United States Navy were flimsy, the lenses tended to pop out easily, and his prescription was not a standard one, so getting it right was a perennial problem.

I scrolled down the page, browsing the responses to each question. One…two…three…I smiled when I saw the answers and the detail to each. Then I got to the last question, number four.

“In your letter dated February 9, 1945, you say, The place is about deserted now. You’ll just have to guess why and read the papers. Do you remember what you were talking about?”

The space below it was blank. Maybe he didn’t notice it, I thought. But before the thought was even complete, I knew it was unlikely. My dad didn’t miss things like that.

Perhaps he’d answer it later. I checked my email periodically over the next few days. Still no answer.

Finally convinced that an answer was not forthcoming, I printed off a copy of the email, grabbed the notebook, and drove over to my parents’ house. I didn’t know what to expect but I knew I had to try.

When I pulled into the driveway, the double garage door was up and he was hammering away at something in the shop inside.

“Hi, Dad,” I said coming up behind him.

“Well, hello,” he said smiling. “What’re you doing here?”

He glanced at the paper in my hand.

“The email,” I said cautiously. “There was one more question. You probably didn’t see it.”

“Hmm,” he said.

He went back to hammering.

I stood behind him, waiting. Maybe he just needed to finish what he was working on. I waited some more. He didn’t look back, not even a glance over his shoulder. As the noise continued, I slowly came to the realization that he wasn’t going to respond to me. So I slowly turned and went inside the house.

Mom greeted me at the door.

“You look nice,” I said.

Though in her seventies, she always had someplace to go, a meeting, a church group, or lunch with friends.

“Thank you,” she said. “What do you think of the necklace with this?” Mom always dressed stylishly in slacks, colorful blouses, and coordinating jackets. “Does it look OK?” she asked.

“It looks great,” I said.

“Oh, good. I’m meeting a friend at the church in an hour,” she said.

She went into the other room and returned with a box of chocolates. She opened the box and set it on the coffee table in front of me and then sat on the sofa with her back to the picture window. The sun made her silver hair sparkle like glitter.

“I’ve been reading Dad’s letters,” I said. “And I emailed him some questions.”

“I heard,” she said, pursing her lips. “He printed them off to show me.”

“Did he tell you he didn’t answer all the questions?” I asked.

“No,” she replied. There was no surprise in her voice.

“Listen to this,” I said.

I glanced at the front door before reading from the letter dated February 9, 1945.

Well, guess you know by now what my deal is here, I read.

“And then this,” I added. The place is about deserted now. You’ll just have to guess why and read the papers.

I looked at her and squinted.

“I asked him what he meant when he wrote that,” I said. “He answered all the other questions, but not this one.”

“Well, he’s in the garage, ask him,” she said.

“I know,” I responded, looking over the chocolates. “I tried to ask him but I don’t think he wants to answer. He was hammering away at something.”

A little bit later, Dad walked through the living room to the kitchen without looking at me. I heard the water running as he washed his hands. When he returned, he sat down in the recliner and set his Bowfin submarine cap on the end table next to him. He smoothed his hair to one side.

“Why are you doing this?” he asked.

“I don’t know, Dad. All I do know is that these letters are a gift, and I want to understand what’s in them. I just want to know more. I can’t explain it.”

“It was Iwo Jima,” he said abruptly. “That letter I wrote must have been referring to Iwo Jima. It was in all the newspapers. So many guys were sent out that the base was pretty much deserted. I couldn’t talk about it in my letters because of the censors, but I knew my folks would be reading about it in the newspaper back home.”

“What exactly was Iwo Jima?” I asked.

“Well, you know,” he began, “Iwo Jima was just a tiny island. It was only about five miles long and maybe two miles across. Admiral Nimitz wanted the island for a place to refuel our B-29s. You’ve probably seen the photograph of the marines raising the flag on Iwo.”

I nodded.

“That became the most famous photograph of WWII,” he explained.

As he started to talk, I remembered the notebook and pen I’d brought. They were in my purse on the floor, but I was afraid he’d stop talking if I looked away, even for a moment. So I kept my eyes on him. He stared at the blank television screen as he spoke, but it felt like he was staring at me. I didn’t move.

“So the flag was raised after they’d overtaken the island?” I asked.

He laughed, a sparkle in his eyes.

“The thought was that it would only take a few days to take the island from the Japs,” he said. “That’s what we called them back then: Japs. Anyway, our guys went in and strafed the beaches.”

“Strafed?” I asked.

“Oh, you don’t know what strafing is, do you? I suppose you wouldn’t. Strafing was when you sent up these small planes and they flew in low, shooting up the beaches. We…they…could see that sand and dirt and dust in a cloud over the beach. Every grain of sand was turned over several times. Everyone thought the Japs were hiding by burying themselves in the sand. And I suppose a few were. But for the most part, I don’t think it helped at all. The Japs had an elaborate tunnel system on that island. They were in caves that were connected by tunnels all through it.

“So, back to the flag. It was raised on Mount Suribachi four days after the initial landing. We…they…could see it from the water. But it took a total of thirty-five days I think, before we had taken the whole island.”

He sat back in his chair and looked out the window.

“So that’s the story,” he said.

My mind was whirling. Had he misspoken when he said “we”? Or was there something more to it? Clearly, he was done talking. He was quiet now, as if in deep thought. Time passed as we sat silently. There was something about his demeanor that held an invisible hand up, refusing to let me pursue it.

“Are you going to Caleb’s soccer game?” I finally asked.

He was quiet.

“Dad?” I asked.

“What?”

“Caleb’s game?” I asked again.

“Oh, yes. We’ll be there. What time does it start?”