Northern Bald Ibis or Waldrapp

(Geronticus eremita)

In February 2008, I met Rubio, one of thirty-two northern bald ibis or “waldrapp” that live at the Konrad Lorenz Institute in Grunau, Austria. These birds are about twenty-eight inches in length with the long curved bill that characterizes all ibis. They have a distinctive fringe of plumage around the nape of their necks, but their heads are bare with no facial or crown feathers except during the juvenile stage. I had hoped to sit on the grass while they flew freely around us, as they normally do, but unfortunately all were temporarily confined because the rate of predation had been unusually high.

I went into the huge flight aviary with one of the keepers and Dr. Fritz Johannes, who is in charge of the project. Seen close up, they were beautiful, for we were lucky with the weather: The cold winter sun brought out the glorious iridescent sheen on their almost black plumage, and shone on their long pink bills and pink legs. The juveniles, whose feathers are bronze, had not yet lost their feathered caps.

At first the birds preferred to take mealworms from their keeper and from Fritz, but then Rubio decided I was okay, too, and transferred from Fritz’s shoulder to mine. Having consumed an inordinate number of mealworms, he began the serious business of grooming me. What really amazed me was how warm his beak felt, and how delicately and gently he used it as he preened my hair. He also made attempts to probe into my ears and nostrils—I must admit I was not too thrilled about that!

Eventually he was persuaded to return to his keeper—but not before he marked me with white liquid down the back of my jacket. This, of course, is a sign of good luck, so I tried to feel grateful!

I had the huge good fortune of visiting Rubio, one of the hand-reared northern bald ibis in Austria, who are being taught to migrate south for the winter by following ultralights. (Markus Unsöld)

I was there, with the team from JGI-Austria, to learn about the attempt to teach the waldrapp to migrate from Austria to the south of Italy. In the flight aviary next to Rubio’s were the birds that would take part in the spring migration over the Alps.

Extinction in Europe

This ibis once ranged in arid mountainous regions from Southern Europe to northwestern Africa and the Middle East. Today, however, it is an extremely rare species, extinct throughout nearly all of its range as a result of pesticide use, habitat loss, and hunting for its tasty flesh. The last waldrapp disappeared from Europe in the seventeenth century. In the 1980s, after all the individuals from the last remaining wild colony in Turkey had been captured for captive breeding, it was thought that the species was extinct in the Middle East.

Between 1950 and the end of the 1980s, the last migratory colonies in the Moroccan mountains vanished. Fortunately, however, birds from that colony had been captured during the 1960s for exhibition in European zoos, and they became the founder individuals for an international zoo breeding program. I saw descendants of those original captives in Innsbruck, where they have been bred for forty years.

By 2000, it was believed that only one colony of about eighty-five breeding pairs of (nonmigratory) bald ibis remained in the wild, in the Souss Massa National Park in Morocco. But then, to ornithologists’ surprise and delight, a tiny group was located in the Syrian desert. There were only seven birds, but there were three nests, and they were raising young—seven fledged in 2003.

A Human-Led Migration

The (usually) free-flying breeding colony that I visited in Austria was established in 1997. Waldrapp can survive well in the Austrian Alps during the summer, feeding on insects and other invertebrates, but they cannot endure the winter months in the wild. To create a self-sustaining population, then, it would be necessary that they learn to migrate—as in the past—to warmer climes. And so a feasibility study (based on the pioneering work with Canada geese and whooping cranes described in the last section) was planned to find out whether the bald ibis could also learn to follow ultralight planes—or trikes, as they’re called—on a migration route over the Alps to Tuscany in Italy.

Unlike the whooping cranes—which, as we have seen, are raised by caretakers wearing strange white gowns to prevent them from imprinting on humans, these ibis are hand-reared and bonded closely with their caretakers. They are exposed to the sound of the trikes, and the foster parent—Fritz’s wife, Angelika—wears the helmet she will don when flying the plane.

During training, the birds initially flew too far away from the trike, despite Angelika’s constant calling. But their performance gradually improved, and the first successful migration started out on August 17, 2004, with nine waldrapp following two trikes. Just over two months later, on September 22, the trikes arrived, along with seven of the waldrapp, at the chosen wintering ground, Laguna di Orbetello, a WWF nature reserve in southern Tuscany. (The other two waldrapp failed to make the journey on their own and were brought along in boxes.)

The following year, using a different trike (with old-fashioned wings and more powerful engine), the same route was followed and, with fewer stopovers, took only twenty-two days, from August 18 to September 8. Because this trike could fly at a lower speed, the birds were able to follow more closely so that the whole operation went more smoothly.

During the winter of 2004–2005, following their arrival in Tuscany, the young birds stayed close to the night roost, seldom venturing much more than half a mile. However, when summer came they began to go on longer flights—up to twelve miles—before returning. And some were seen along the migration route, heading for Austria. After some weeks they returned to Tuscany, but it seemed that the instinct to migrate was still present, and Johannes, Angelika, and the rest of the team were much encouraged.

In spring 2006, all the birds who had followed trikes from Austria to Tuscany in 2004 went on long flights while those from a second successful migration in 2005 remained in the wintering area. Thus it seems that as they get older, they are more likely to leave for the breeding grounds in Austria at the time of the spring migration, and that this is genetically programmed.

That 2006 spring was an exciting time for Fritz, Angelika, and the rest of the team. They received a number of reports of sightings, mainly from bird-watchers and hunters, of individual waldrapp that had gone on these long flights—some as far as three hundred miles. Most of them had retraced the route they had been shown by humans. A few were way off course. In some cases, this may have been because, during their human-led journey, they had been carried part of the way in their boxes (the few that were not following the plane and had to be collected); thus their “memory” of the journey was incomplete.

Finally, in spring 2007—success! Four of the waldrapp who had been led south from Grunau in 2004 had become sexually mature, and to everyone’s delight they flew to Austria. These were the female Aurelia and the males Speedy, Bobby, and Medea. They all returned to Grunau safely—“the first complete migration circle of the birds independent of humans,” Fritz told me proudly. Places chosen for stopovers were not necessarily the same as those where they’d stopped during the human-led migration, but seemed determined by the type of habitat. Once back, Aurelia bonded with Speedy: They bred and raised three offspring.

The 2007 autumn migration to the wintering grounds in Tuscany started with some confusion, as the seventeen migratory birds got mixed up with the almost forty free-flying birds at Austria’s Konrad Lorenz Institute. There they lost their motivation to migrate, preferring to stay with the others instead of heading south. It was finally decided to catch the confused birds and release them about thirty-five miles southward. One adult and one of Aurelia’s juveniles evaded capture and stayed in Grunau, but four adults, including Aurelia and Speedy with their remaining two offspring, headed south as hoped.

Some of the birds were fitted with a GPS data logger. This stores the position of the bird every five minutes and can be downloaded, once the bird is in range, so that researchers can reconstruct the flight path in detail. The data showed that they had exactly followed the route along which they had been led in 2004. On September 15, Medea, Bobby, and Aurelia with her offspring—but not Speedy—were seen in Osoppo, northern Italy. Five days later—one day after the parallel human-led migration ended up at Laguna di Orbetello—Aurelia (without her offspring) and Medea also arrived in Tuscany. Bobby arrived two weeks later, but the two juveniles have not been seen since.

And what of Speedy? His story is fascinating. Even during the first migration, he flew separately from the others. In spring 2007, he started alone, flying to northern Italy, then on to Slovenia and from there to Austria. Not stopping, he continued on to Styria, near Leoben, then farther northeast until he was close to Vienna. There he turned back to Styria, where—miraculously—he met up with Aurelia and Medea. He and Aurelia then flew together to Grunau.

Then in the autumn, when the group set off to fly back to Tuscany, Speedy once again separated from the group. This time he had been selected to carry a satellite transmitter instead of GPS. This technology only stores some positions every third day, but the advantage is that the researchers get these positions in real time.

Flight formation of the ibis in northern Italy, as seen from an ultralight. (Markus Unsöld)

All seventeen waldrapp at the start of the 2007 autumn migration. (Markus Unsöld)

Unfortunately, the device did not work—only transmitting one position on September 18. But this was a very interesting data point, because it was exactly on the flight route—which had been reconstructed from Speedy’s spring GPS data—that he had followed in the spring. In other words, he was retracing his own unique flight path back to Tuscany. “We got no further satellite positions and also no sight report,” said Johannes. Speedy seems to have disappeared. “Nevertheless,” he told me, “the migration of these adult birds was a great success for our project. Aurelia, Medea, and Bobby are the first free-living, independent, migratory northern bald ibis in Europe after about four hundred years! That’s a great motivation for us.”

One Step Closer to Success

As I sit writing this chapter in Bournemouth, in August 2008, I receive an e-mail from Johannes in Slovenia. He tells me they are trying a new route, as a result of the problems of the previous year. Now they are leading the young ibis around the Alps instead of crossing them—and “it is fantastic till now,” he writes. The birds have performed well, flying more than sixty miles per day, much farther than in previous years.

And there is also news of the six older sexually mature birds that had learned to follow the trikes. In April, they migrated northward from Italy to Austria. As during the previous year, they ended up in Styria, about fifty miles from their breeding place. All six were then taken to a small village in northern Italy close to the original migration route, where a suitable aviary had been prepared. One pair has bred and successfully raised two birds. The aviary was opened in July. So far the birds have remained close by, but Johannes expects that all eight “will start the migration within the next ten days.” If the group reaches Tuscany—“and there is a good and realistic chance of that,” says Johannes—“then we could definitely show that human-led migration is a suitable methodological tool for the introduction of independent, migratory groups of northern bald ibis.” That will be a great success for the team.

Johannes ends by telling me of the plan to start a new project in 2009 in the Moroccan Atlas region, one of the most important breeding areas for northern bald ibis until the 1980s. The first step will be to explore the food availability in a region in the northern Atlas with some hand-raised ibis.

I think of him, there with his wife and the rest of the team, getting ready for the next flight on the way to Tuscany. And if I close my eyes, I can imagine myself back in the aviary in Austria, sitting with Johannes and Rubio. There I fell in love with these endearing birds, so totally different from whooping cranes. I can almost feel the gentle touch of Rubio’s warm pink beak as he groomed me. When it had been time to leave, I had given him the last of the mealworms and, reluctantly, left the colony—to continue with my own, never-ending migration around the planet.

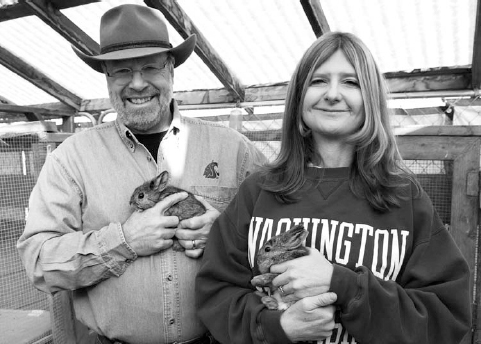

Rod Sayler and Lisa Shipley are working tirelessly to ensure the pygmy rabbit’s survival. Shown here at the endangered species breeding facility at Washington State University, Pullman. (Shelly Hanks)