Iberian Lynx

(Lynx pardinus)

I first read about the Iberian lynx in the Iberian Air magazine Ronda Iberia in June 2006, when I was on my way from Spain to the UK. Endemic to the Iberian Peninsula, this lynx, I read, is one of the world’s most endangered felines. The article introduced Miguel Angel Simon, a biologist who was heading up a lynx recovery plan. Immediately I wanted to meet with him.

And a year later, when I was in Barcelona, it happened: Miguel Angel flew in from his field station to talk with me. I found him sitting at a table in a peaceful area of my small hotel with Ferran Guallar, executive director of JGI-Spain, who offered to translate for us. Miguel Angel, a wiry man with a short military mustache, looked business-like and competent, and was clearly passionate about his work with the lynx.

It was 2001 when Miguel and his team began the first thorough census of the lynx population throughout Andalusia. They set up photo traps and searched for signs of lynx presence such as feces. The results showed that the species was in serious trouble. Not only were the lynx affected by habitat loss, hunting, and being caught in traps set for other animals, but rabbits, their main prey species, had been almost eliminated by an epidemic. Indeed, in some places they had disappeared entirely from this land the Phoenicians called Hispania, meaning “land of the rabbits.” Undoubtedly, Miguel said, many lynx had died from starvation. His census showed that there were only between one and two hundred lynx remaining in two areas in southern Spain; during the previous twenty years, they had become extinct in central Spain and Portugal. Clearly desperate measures would have to be taken if these beautiful animals were not to become extinct.

Astrid Vargas and her staff work around the clock to save Spain’s treasured Iberian lynx. Shown here with a young male, Espliego, abandoned by his mother, Aliaga. (Jose M. Pérez de Ayala)

Winning Friends for the Lynx

An application to the EU for funding resulted in one of its biggest-ever grants for work with an endangered species—twenty-six million euros for the period from 2006 to 2011. The lynx restoration program was established with eleven partners: four conservation groups, four government ministries, and three hunting organizations. Because most of the surviving lynx were on private land in the rural boroughs of Andujar in Jaen, Cardena in Cordoba, and Doñana in Huelva, it was clearly of utmost importance to strive for the full cooperation of the landowners.

At first, this was not easy. A lynx will prey on fawns, and many farmers had concerns about lynx also killing their lambs—which they sometimes do. And so, from the start, Miguel and his team investigated every report of lamb killing and gave compensation to farmers—even if it turned out that the killer had been a wolf. A scheme was launched whereby awards were given to landowners who had good conservation records.

Gradually the landowners’ attitude changed. More and more of them, whether they owned fifteen thousand acres, or fifty acres, or simply a summer villa with a garden, signed agreements with the lynx recovery team. First—they would protect the lynx on their land. Second—they would no longer shoot rabbits, but rather leave them for the lynx. Third—they would permit those working on the lynx recovery plan to use their land for controlled reintroductions (of lynx and rabbits) and monitoring. Indeed, it has become something of a status symbol to claim that you have lynx on your land—after all, in some places the lynx is actually a totem animal. Thus the lynx is now protected, through ninety-eight separate agreements, throughout an area of some 540 square miles.

Of course, Miguel told me, recovery is agonizingly slow. A female has cubs only every other year, and normally she will not raise more than two young at a time. Nevertheless, in 2005 at one of the main research sites, some twenty females gave birth to about forty cubs in the spring. And by autumn approximately thirty young lynx had survived. But this is the time, Miguel told me, when the trouble starts, as the young adults leave to find new territories. The males leave when they are a year old. The females may hang around for another season. Whatever their age, many simply vanish when they go off on their own. But according to Miguel, they have now started using radio collars for GPS satellite tracking; it is finally possible to find out where the animals go.

I asked Miguel if he had a good story to share and he told one that proves, he says, that the conservation program is working. In 1997, in one area, there were only seven adult lynx (identified from photo traps)—two females and five males—and just one cub. Nobody thought the tiny group had a chance of surviving, especially because disease was spreading among the rabbits. Nevertheless, the son of the ranger in charge was asked to name the cub. The little boy, without hesitation, chose the name Pikachu. And, to everyone’s amazed delight, Pikachu—along with all seven adults—survived. Today there are forty-five lynx in the area. “And,” said Miguel, “Pikachu is king.”

A Visit with the Lynx

Written into the recovery program was the decision to establish a captive breeding program. A team of scientists, who work closely with Miguel and his team, carefully determine which lynx, from which areas, should be taken into captivity in order to ensure genetic diversity. The rules are strict: Only if three cubs from one female survive to six months of age can one of them be captured. The cubs are sent to one of the two breeding centers.

Miguel works closely with Astrid Vargas—who heads up the El Acebuche Centre in Doñana—and he introduced me to her by phone. A year later I was landing in Seville, with my sister Judy, for the drive to the breeding center. Astrid herself was unable to meet us at the airport because there had been a tragedy during the night. She had been woken by the volunteers who monitor the breeding females and cubs via TV monitors. They told her that there had been a serious fight between cubs—the sixth within the past month. This time it was Esperanza’s youngsters. By the time Astrid arrived, the female cub had received a lethal bite to her throat.

I learned that it was the second death caused by cub fighting since the start of the breeding program. Thus it was a somewhat subdued team that greeted us when we arrived: Astrid, Antonio Rivas (Toñe), Juana Bergara (the head keeper), and some dedicated volunteers. It was not surprising that they were upset—they showed me the footage of the aggression later, and it was shocking in its sudden onset and its ferocity.

Astrid told me that she could never forget the first time sibling murder took place at the breeding center. The mother was Saliega, known as Sali, and she was the first female ever to give birth in captivity. She was an excellent mother, and her three cubs were all doing well—until, when they were about six weeks old, a play bout between the largest cub, Brezo, and one of his sisters suddenly turned deadly serious and they began to fight fiercely. Sali seemed perplexed and tried to break it up, holding one or the other of the pair with her jaws, shaking them. But Brezo would not let go, and in the end, badly wounded himself, he killed his sister with a bite to her throat.

“We suddenly went from a happy family to an awful crisis situation with a dead cub, an injured one, and a completely stressed-out mother who would repeatedly take the third cub in her jaws and pace all over the enclosure,” said Astrid.

Frantically Astrid contacted as many experts as she could. Finally she got through to Dr. Sergey Naidenko, a Russian scientist who had studied the Eurasian lynx for twenty years. And, he told her, for eighteen of those years he had recorded sibling aggression among captive lynx and he had come to think that it was normal behavior. But no one had believed him—it was always ascribed to bad management. Astrid was delighted to speak with Naidenko. “It was like finding a guru,” she told me.

She asked him if he’d had success returning injured cubs to their mothers, and he said yes, 100 percent success. But, he warned, it would have to be done very carefully. At this point, Astrid had to make a tough decision: She knew Brezo needed his mother and her milk, but she also knew that the media and wildlife authorities were watching closely. What if she made a wrong decision and it led to the death of another precious lynx? She would be blamed, perhaps damaging the status of the whole breeding program. But because their goal was to return lynx to the wild, it was vital that the cubs be raised by their mothers. So she decided, with much apprehension, to take the risk.

Brezo had been away from his mother for a day and a half. First they sprinkled him with Sali’s urine—she often sprayed her cubs. “We tried,” said Astrid, “to cover as much as possible our human smell with Sali’s own perfume.” As soon as Sali saw Brezo, she began “vocalizing sounds of joy.” Once he was in the enclosure, she groomed him and sprayed him and lay down so he could suckle. “Brezo was in lynx heaven,” said Astrid, “and we were so happy and deeply touched by the scene that I still get chills when I recall it.”

Since then, the team has broken up fights in several subsequent litters. They always occur when the cubs are about six weeks old, and for no apparent reason.

Mothers and Cubs

I was able to see firsthand how much Astrid cares for the lynx in the program. She and the head keeper, Juana Bergara, took me first to visit Esperanza, mother of the cub killed the night before. Despite this trauma—or perhaps because of it—she was clearly very, very pleased to see Astrid and Juana. Although all the lynx cubs at the center are raised with limited contact with humans, and prepared, as far as possible, for survival in the wild, Esperanza had been hand-raised and had a special relationship with people.

As we approached, wearing protective booties and rubber gloves, she gave little breathy sounds of greeting and rubbed up against the wire. She repeatedly butted the wire mesh with her head—a sign of affection, Astrid said. Clearly, she could not get enough of this attention—I had the feeling that this contact was soothing for her after the stress of the night. I heard her purring like a happy domestic cat. She had been found in 2001, Astrid told me, as an almost dead one-week-old lynx cub. She was saved by the Jerez zoo vets and hand-raised. She never saw another lynx until she was almost a year old.

To provide opportunity for the cubs to learn from their mothers, the families are kept in large outdoor enclosures, where the cubs are taught to hunt by their mothers. Rabbits, of course, are bred for this purpose. In one of the big enclosures, three cubs were playing. Their mother led them toward a handsome black rabbit, but they showed absolutely no desire to want to hurt it, nor did the rabbit show the slightest fear. It almost seemed to want to play! The keeper told me that one of the lynx refused to kill one individual rabbit that remained in the enclosure for several weeks—and thereby witnessed the quick dispatch of many others of his kind. This, of course, is the difficult part of such programs. Astrid told me that she always feels so sorry for the rabbits. It makes it worse that her son, Mario, now four years old, always wants to go and see the rabbits when he visits the facility. And he always asks to bring them home.

Astrid took me to visit two of the breeding males—they are stunningly beautiful creatures. One lay quite far away, watching us intently. The other was close to the mesh, but spat and hissed at us as we approached. He had lived in the wild until he was three years old, Astrid told me. Then he was brought to the center too badly injured to be released. As we watched him, Astrid was reminded of another injured lynx, Viciosa, who had been sent to her from Andalusia, and I remembered Miguel telling me about her when we met in Barcelona. When he had found her, by following signals from her radio collar, she’d been close to death. She had been badly injured by fighting during the breeding season, and weighed only eleven pounds instead of the average twenty-four pounds or so. Amazingly, with good care and good food, she recovered in three weeks.

When Astrid received her, she had already been saddled with the name Viciosa (which means “vicious”) by Miguel’s team. “But she wasn’t at all vicious,” Astrid told me, “she just wanted to eat and eat!” When Viciosa was released back into her territory toward the end of breeding season, she immediately coupled with a male, and nine weeks later gave birth to two cubs.

I was very impressed by Astrid’s facility. There are cameras mounted to cover each outside area and others for the inside of the dens. The TV monitors are on twenty-four hours, monitored by staff or volunteers, throughout the whole year, and with particular intensity during the three months of birthing and cub rearing. All this footage is providing unique information about lynx behavior.

I was astounded by a truly unique method for collecting blood. Any attempt to anesthetize the lynx, or handle them in any way, is extremely distressing for them. A German scientist had the idea of collecting blood by means of a giant bedbug! Lynx sleep on a layer of cork at night. A small hole is cut in this, and into this space a hungry bedbug is placed. It makes a beeline—or bugline!—for the warm body and starts to suck blood. After twenty minutes (when the bug starts to digest the blood), it is removed from below the sleeping platform, and the blood removed with a syringe. The lynx sleeps on, undisturbed. And the bug can be used again! (No doubt this will cause outrage among People for the Ethical Treatment of Bedbugs!)

A Tragic Killing

Before we left, Judy and I saw the infrared footage of the night’s fatal attack. It lasted eight minutes. It began when the victim, up on a ledge in the night quarters, was suddenly, for no apparent reason, attacked by her brother from the back. Then the two started fighting in earnest. The victim, from the start, went on the defensive, lying on her back and kicking with her back legs. After two minutes, the kicking stopped. Esperanza had rushed to the scene instantly and, seizing the victim, tried to pull her away. Three times she managed to separate them, but the aggressor would not give up. Astrid had been called and was there within five minutes—but although she retrieved the cub, it was too late to save her. She had a punctured lung and several broken ribs.

After the dying cub had been removed, Esperanza behaved strangely. Every time the survivor tried to return to the den, his mother—who seemed unable to carry him in the accepted manner, by the scruff of his neck—dragged him out despite his attempts to resist. This was repeated many times. For some reason Esperanza did not want him in that den.

Later I heard from Astrid that a careful necropsy had shown that the actual lethal wounds had not been inflicted by the male sibling, as had been thought, but by the mother in her efforts to try to separate her cubs. “Esperanza,” Astrid told me, “was always attentive yet rough with her cubs. Her instinct to separate these two was good, but she was captive-raised, had no lynx playmate as a cub, and thus had no chance to learn her own strength. And that,” said Astrid, “was lethal.”

The Future of the Lynx in the Wild

That evening Astrid, Toñe, and Javitxu drove Judy and me into the Doñana National Park lynx habitat. Of course we saw no lynx, though Javitxu told us that just the previous week he had seen a mother with three cubs playing in one of the many open clearings among the low trees.

During the drive, we discussed the many difficulties and the many problems that lie ahead—the protection of suitable habitat, for one thing. Even the national parks are not always safe. Part of Doñana National Park’s buffer zone had been taken over for a golf course. Also, each year, hundreds of thousands of people make a pilgrimage to the Virgin of Rocio festival, in honor of a statuette of the Virgin Mary that once supposedly magically appeared in a tree. Unfortunately, the pilgrims pass through prime lynx habitat, right through the national park, in the middle of the breeding season. Then, too, there are more tourists coming into the area, attracted by the beautiful beaches. And as road traffic increases, so do the numbers of lynx killed on roads (at the time about 5 percent of all deaths).

Nonetheless, as we discussed over a delicious dinner in a small and friendly restaurant, there is much that is positive. For one thing, the lynx population in Doñana is now stable at about forty to fifty individuals. It is of course the number of breeding females, and the number of young born each year, that counts. During recent years, there have been ten to fifteen females.

And work has started on the construction of tunnels under the roads in the hope that the lynx will learn to use them—as animals do in other places. They are thinking about building bridges over the roads, too. Finally, and most importantly, they are working to increase the number of rabbits.

We poured the last of the Spanish red wine and raised our glasses to the restoration of the Iberian lynx and the dedicated people who are devoting their all to making a dream come true.

Postscript

Later, in the fall of 2008, I heard from Astrid that the captive breeding program was, by mid-2008, ahead of projections. There were, she said, fifty-two lynx in captivity, twenty-four of which were born in the facility. This means, said Astrid, that provided the release area is ready for them, reintroduction of captive-born lynx could take place in 2009—one year ahead of schedule. And because not one Iberian lynx had been killed in a road accident in Doñana since late 2006, it seems that the area may be suitable for reintroducing captive-born lynx.

I then heard from Miguel that the number of territorial breeding females was up to nineteen, and there were between seventeen and twenty-one new cubs alive in September 2008. While the verdict is still out as to whether or not Spain’s magnificent Iberian lynx will once again have a suitable habitat that allows it to thrive in the wild—a protected area that is safe from pilgrims, golf courses, and the like—for now the news is encouraging.

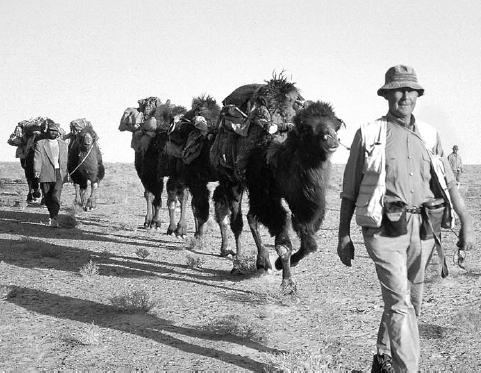

John Hare, adventurer, explorer, and passionate advocate for the wild Bactrian camel, shown here with domestic Bactrian near the northern border of Tibet, surveying a sanctuary for their highly endangered wild cousins. (Yuan Lei)