Part of the discrepancy in ground troops would be made up by the Fifth Fleet. The navy's carrier-based aircraft had struck Peleliu hard already and would soon return. Days before the invasion, the fleet's great battlewagons would circle the tiny island. Salvos from dozens of five-inch, twelve-inch, and sixteen-inch guns--the latter far larger and more destructive than land-based artillery--would unleash a firestorm of unheard-of proportions. Nothing would survive. The Japanese empire had no navy with which to impede, much less threaten, the U.S. fleet, although the admirals certainly looked forward to the next sortie by the remaining Japanese carriers so as to complete the job left unfinished near Saipan. Men had taken to calling the carrier battle near Saipan "the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot" because scores of Japanese pilots had been killed. Peleliu, well south of the Marianas, was not expected to become the setting for the final carrier battle. The Japanese, however, had to stand and fight sometime, somewhere.

The Japanese on Peleliu who survived the Fifth Fleet's shellacking would be overwhelmed by speed. At 4.5 mph, the waterborne speed of an amtrac did not seem like much. The staff estimated the trip from the reef to the beach would take fifteen minutes. Enough LVTs had been promised, though, to create a giant conveyor belt. At H hour, amtracs with the 37mm antitank guns would crawl ashore and drive inland to blow up bunkers. One minute later the first wave of marine riflemen would land, with more waves landing every five minutes. In twenty minutes, five battalions of forty- five hundred men would be on their assigned beaches. Immediate fire support would come from the division's tanks, whose flotation devices enabled them to make the trip from the reef to shore, as well as from the 75mm pack howitzers loaded in some of the amtracs. The regimental weapons companies would begin landing five minutes later, their larger 105mm howitzers brought in by "ducks" (floating trucks officially designated DUKWs) fitted with a mechanical hoist. In the meantime, the empty amtracs would drive back out to the reef, pick up more troops, and return. Eighty-five minutes after H hour, three more infantry battalions would be ashore. Eight thousand combat marines would sweep across Peleliu as the first of the division's seventeen thousand support troops landed to provide the supplies and logistics to sustain the drive.

Colonel Shofner, who had fought the enemy with a few rusty World War I Enfield rifles as a guerrilla on Mindanao, must have been amazed by the sophistication of the technologies and organizations that made such offensive might possible. Even better, he could control some of it himself. Shofner would come ashore with his own team from JASCO ( Joint Assault Signal Company). It consisted of a naval gunfire officer, an aviation liaison officer, and a shore party officer, as well as their assistants and communications equipment. "Once ashore," the assault plan stated, "the Battalion Commander had only to turn to an officer at his side and heavy guns firing shells up to 16 inch or planes capable bombing, strafing, or launching rockets were at his disposal."176 Now that was fire support.

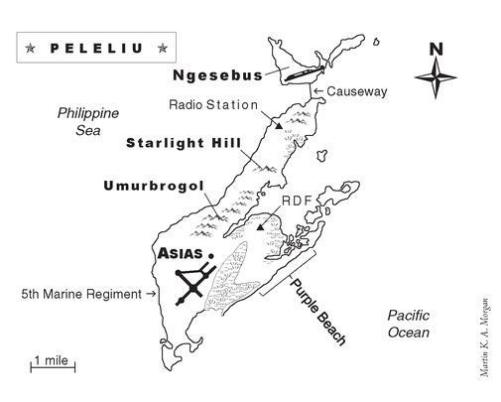

Harris picked Shofner's 3/5 to land at H hour, next to the 1/5. The 2/5 would land behind them. The Fifth would drive across the great flat plain of Peleliu, some of it jungle and some of it the airfield. By reaching the far shore, the Fifth Marines would cut the defenders in half and be in possession of most of the airfield. On Shofner's right, battalions of the Seventh Marines would assault the rocky little southern tip of the island. Once they secured the tip, the Seventh would turn north, cross through the Fifth's area, and help Chesty Puller's First Marines. The First Regiment, because it would come across Peleliu's northern beaches, faced the challenge of seizing the high ground north of the airfield as well as the enemy's main troop concentration. The invasion barrage by the navy's battlewagons would engage the enemy bunkers on the ridge while the marines stormed ashore. Four hours after landing, the 155mm artillery of the Eleventh Marine Regiment would have come ashore behind the Fifth and stood ready to mass fire on any hard points in front of the First or the Fifth.

Shifty's battalion's landing on Orange Beach Two would be led by Item and King companies, with Love Company following. His company commanders received maps of their specific areas with scales of 1 to 5,000 and 1 to 10,000. The rifle companies trained for their specific missions as best they could on a tiny island with too few LVTs and too few tanks. When the assault LVTs arrived, they mounted a snub-nosed 75mm howitzer, not a 37mm antitank gun as shown in the operator manuals distributed to the men who were learning to drive them.

EUGENE SLEDGE NOTED NO SPECIAL INTENSITY OF THE TRAINING LATE IN THE summer. He did notice an additional sergeant had joined K/3/5. Sergeant "Pop" Haney had a reputation for being more than a little loony, or "Asiatic," as the saying went. Burgin called him a "crazy jap killer," because Pop Haney had earned a Silver Star on Cape Gloucester. The word was Haney had served with King Company in World War I. He kept being rotated or transferred, but whenever the shooting was about to start, Pop came back to King. With only twenty- four veterans of the Canal in his 240-man company, Captain Haldane gave Haney permission to attach again.177 The old and grizzled vet joined the young marines on their marches, mostly keeping to himself.

Eugene kept his mind off the drudgery and boredom of training by watching for birds. The habits and mannerisms of the blue kingfishers and white cockatoos delighted him. As on New Caledonia, the cockatoos seemed to look down from the coconut trees with resentment. "I think the birds are the only ones who want the groves. I know I don't." The red parakeets left red streaks as they flew through the jungle. A marine caught one and he let Gene put it on his shoulder. The bird "climbed on my arms and head and had a big-time scratching in my hair." In the evening, Gene might relax by watching the bats leave their nests high up in the palms to hunt. Sergeant Pop Haney, meanwhile, frequently decided that he had not performed well during the day and assigned himself extra guard duty or conducted a bayonet drill solo.178 The sight of Pop disciplining himself struck everyone as weird. Pop's vigorous use of a GI brush--with bristles so stiff they'd remove skin--to scrub his body clean was painful to watch. Sledge, who had memorized many of Rudyard Kipling's poems about fighting men with his friend Sid, must have seen the resemblance Pop Haney bore to Kipling's famous character Gunga Din.

The arrival of Pop Haney and more LVTs brought lots of scuttlebutt about the upcoming mission. As Eugene anticipated his first taste of combat, he received a newspaper clipping announcing that Lieutenant Edward Sledge had been awarded the Silver Star. Gene read the citation aloud to the men in his tent and showed the clipping's photo of Ed accepting the award. Gene knew he should be and was proud of his older brother, but the hill he felt he had to climb had become steeper.

SID PHILLIPS HAD GIVEN UP TRYING TO CALL HOME. LONG LINES OF MARINES stood in front of the few phones at the San Diego Recruit Depot. He sent a letter saying he "was back in the U.S.A. and would be home as soon as we are processed." In early August he departed on a troop train that wound its way through New Orleans. Sid stepped off in Meridian, saying good-bye to "Benny," Lieutenant Carl Benson, who had trained the #4 gun squad and had commanded the 81mm mortar platoon. The months of pot walloping to which Benny had condemned him left no hard feelings with Sid.

A bus took Sidney home to Mobile. He called home from the station. His family arrived soon thereafter. All of his hopes for a joyous reunion came true. "My family treated me like I had returned from the grave, and we stayed up and talked until almost to dawn." Sid found it hard to speak at first. Years of service with the Raggedy-Assed Marines, where most every other word was a cussword, forced him to concentrate on his speech to prevent something dreadful from tumbling out of his mouth. At last everyone went off to bed and he lay in his bed, in the room in which he had grown up, unable to close his eyes. He had a whole month of furlough before his war began again.

BOMBING TWO AND ITS TASK GROUP SPENT EARLY AUGUST BACK IN THE BONIN Islands. Lieutenant Micheel and his division made the third strike on a convoy of four troop transports and their escort destroyers in the port of Chichi Jima. The target brought out the reckless streak in them. The wolves increased their dive angles somewhat to score hits. Clouds of AA flak boiled around them as the Helldivers dropped down into the steep-sided bowl that was Chichi Jima's harbor. They scored two hits and two near misses with their five-hundred-pound bombs. The sorties continued until all of the enemy ships had been sunk. All of the squadrons of Admiral Jocko Clark's Task Group 58.1 roamed at will around the Bonins, seeking out any resistance on Iwo Jima, Haha Jima, Ototo Jima--it turned out that the Japanese word for "island" was "jima."

By early August 1944, Task Group 58.1 owned "the Jimas," just five hundred miles from Tokyo. The men of Air Group Two decided to create the "Jocko- Jima Development Corp." They printed certificates of their initial stock offering, one for each Hornet pilot, certifying the holder of one share in a company that offered "Choice Locations of All types in Iwo, Chichi, Haha & Muko Jima."179 The corporation's president, Jocko Clark, signed the certificates and sent stock share number one to his boss, Admiral Mitscher.

Clark took his carrier group back to Saipan where, on August 9, Admiral Mitscher came aboard the Hornet. All hands gathered on the flight deck in their dress uniforms. Mitscher presented numerous awards to the men of TG 58.1, including Navy Crosses for Admiral Jocko Clark, Lieutenant Commander Campbell, and Hal Buell. Buell had earned his for firing a bomb into an Imperial Japanese Fleet carrier in the Philippine Sea.

WHILE MR. AND MRS. BASILONE ENJOYED THEIR HONEYMOON IN OREGON, President Roosevelt had visited Camp Pendleton to watch the Twenty-sixth Marines practice a full-scale amphibious assault on the Pacific coast. Days later, the Twenty-sixth had loaded up and shipped out, to become the floating reserve for the Third Marines' invasion of Guam. The regiment's departure, as the Basilones learned upon their return, had not noticeably increased the number of available apartments to rent in the town of Oceanside. " The superintendents and landlords all said the same thing; we're all full up."180 Lena thought John should be a bit more assertive. " Tell 'em who you are, you'll get one."

"No," he replied, "I ain't gonna use my name to get no apartment."181 So they continued to live in separate barracks on base. Lena began the process of changing her last name in her official USMC file. John used his last name to bail a few of his marines out of jail for drinking or fighting.182 The regiment's impending departure had encouraged the marines of Charlie Company to be a little overly energetic.

On August 11, they got word they were leaving the next day on buses for the port of San Diego. Johnny found his wife on duty, cooking for the officers' mess. "We might be shipping out," said John, "so I wanted to be with you."183 Lena's friend, who had an apartment in Oceanside, said, "Why don't you take my key and use my room tonight?" Lena accepted. John hung around for her shift to end. The phone rang. It was for John. He had to go back immediately.184 They knew this was it. He was shipping out and it would be months before he saw her again. "I'll be back," he said.

Just after three a.m., the buses carrying two regiments of the 5th Division began rolling out the gate of Camp Pendleton and down the coast highway. As the morning wore on, the word got out. Wives and kids and friends lined the road beyond the gate, waving and cheering as hard as they could as the buses passed.185 At the docks in San Diego, long lines of marines carried their rifles, packs, and machine guns up the gangways of the troopships. John's ship, USS Baxter, departed on August 12, making its way around North Island and into the open sea. With the ship safely under way, a number of dogs appeared on deck--all mascots smuggled aboard.186 The next day they learned over the ship's public address system that they were bound for the town of Hilo, on the big island of Hawaii.

Baxter's Higgins boats took the 1/27 into shore at Hilo a week later. No beautiful native women in grass skirts danced for them.187 They were told to wait. Word came that a polio infection had broken out. The 1st Battalion was quarantined just off the beach in a public park. So they set up their pup tents, dug slit trenches, and waited. The stores across the street, some of which had signs in Japanese, were off-limits. The quarantine order had a hard time sticking, though, when the guys ran out of cigarettes and candy. There was too much time to kill. A rumor ran around that when the marines of the 2nd Division had unloaded here after Tarawa, some of them had seen Japanese faces in the crowd. The Japanese supposedly had cheered when they saw how badly mauled the marines had been. So the marines had fired into the crowd.188

WEEKS OF STAFF WORK AND SOME BASIC MATHEMATICS PRODUCED A DETAILED plan of assault on Peleliu. The "Shofner Group" consisted of the 3rd Battalion, Fifth Marines, totaling 38 officers and 885 enlisted men. To the 3/5 had been attached a platoon of engineers, a platoon of artillery, some pioneers (who unloaded ships), and his JASCO team (who communicated with ships and aircraft). His group also included the amtrac crews driving them to shore and the DUKW crews supporting their assault, so the total reached 1,300 men and 60 officers.189 More than 250 of them, however, drove vehicles. Half of these men expected to serve on the front line in combat.

The combat marines of the 3/5 would come ashore in six waves. Thirteen of the amtracs with the 75mm cannon would land first. Eight LVTs carrying about 192 riflemen landed in wave two. Wave three had twelve amtracs carrying 288 fully equipped marines. Five more of the amtracs with the cannons landed on wave four, followed by twelve amtracs of wave five. The DUKWs carrying the artillery arrived as wave six. This left Shofner with two LVTs to carry ammo; one DUKW to carry the main radio; one LVT to carry part of the division staff; and one amtrac for himself and his battalion HQ. These were scheduled to arrive after the fourth wave. Shofner, under the guidance of his regimental team, also worked out the order of another six waves, by which the reserve company of his battalion (Love Company) and the other essential elements of the Fifth Regiment arrived.

Loading all of these waves had not been worked out because the navy had not sent along detailed information about the number and type of ships. The seventeen troop transport ships for the division arrived August 10, so the staff of Transport Group Three came ashore to work with the marines. The Shofner Group would sail to Peleliu in LSTs, which also carried their LVTs. The flotilla of thirty LSTs for the division arrived on August 11. Assigning his assault teams was easy: King Company would go aboard LST 661, Item on 268, and Love and Headquarters on 271 and 276. The marine officers had come up with a creative way to bring more of their necessary cargo--ammo, spools of barbed wire, drums of drinking water--by loading them first, adding a protective layer, and driving the LVTs in on top. The navy captains rejected the idea of "under-stowing," which just added to the challenge of working out all of these details quickly.190

Like all battalion commanders, Shofner had to fight to get what he needed aboard ship, had to find solutions to a hundred other problems, and had to keep his men on a training schedule. In late August his boss, Bucky Harris, began to worry about Shofner's agitated state.191 The stress seemed to be getting the better of Lieutenant Colonel Shofner, and the stress level only increased. The navy informed the 1st Division that, due to limited space, it could only carry thirty of the marines' forty-six tanks. Although each of his assault squads was entitled to a flamethrower, not enough of the improved M2-2 flamethrower had arrived. Once the marines at last embarked on their ships, someone discovered that the troopships had loaded improperly. The follow-up waves of the Fifth Marines and the Seventh Marines would--unless they changed--have to cross one another on the trip to shore, making it quite likely they would land on the wrong beaches. It had to be rectified. On nine ships, the marines unloaded off of one and loaded onto another. With all of the problems, though, the marines departed Pavuvu on schedule. Their ships lifted anchors on August 26 for the short trip to Guadalcanal.

TASK FORCE 58, THE AIRCRAFT CARRIERS OF THE FIFTH FLEET, RETURNED TO anchorage in the Marshall Islands, specifically the atolls of Eniwetok and Majuro, in early August. All hands enjoyed some time off. A USO show, featuring "five real live girls," performed. Fresh food arrived and was served immediately. When the rest period ended and Bombing Two started to prepare for the next mission, they learned that some big changes had occurred. The navy had decided to give Admirals Mitscher and Clark a rest. Their Task Force, 58, would become known as Task Force 38, as Admiral Bill Halsey took over the helm. Jocko Clark's Task Group 58.1 would become 38.1 under Admiral "Slew" McCain and his leadership team. Clark would remain aboard for a time while McCain and his staff learned the ropes. Another big change, instigated by Clark, arrived simultaneously.

As the new version of the Helldiver, the SB2C-3, arrived at the atoll to replace the older and problematic "dash twos" of Micheel's squadron, fewer of them came aboard Hornet. Clark had had it with the Beast. If the Helldiver could only carry one five-hundred-pound bomb on the centerline rack because of technical malfunctions, the dive-bomber pilots might as well fly Hellcats, the navy's fighter aircraft. It could carry the five hundred pounds, although it lacked a bomb bay. In mid-August Bombing Two received fifteen fewer SB2C-3s and fifteen more F6F Hellcats. The latter would become a new group: the fighter- bombers.

The skipper of Bombing Two gave Lieutenant Micheel command of Hornet's new fighter-bomber wing, which was something of an experiment.192 Lieutenant Commander Campbell might have handed the plum assignment to his executive officer, but for some time now Campbell had acknowledged that Lieutenant Micheel would make a superior squadron leader. Command of Fighter-Bomber Two represented a big step toward that. The former dairy farmer from Iowa had earned the respect of the Annapolis man after all.

On August 26, 1944, Lieutenant Micheel finally escaped the Beast. Mike selected nineteen pilots from Bombing Two to join him as he began operational training in the F6F Hellcat, the navy's fighter. From the airstrip on Eniwetok, they tested the F6F's capabilities as a dive-bomber. Test "hops" acquainted them with their new aircraft. At idle, the aircraft had a distinctive, unbalanced sound because its Pratt & Whitney R2800 engine had eighteen cylinders and ten exhaust outlets.193 Mike immediately loved it. The Hellcat throbbed with power, raced across the sky with tremendous speed, and turned with agility and grace. It flew smoothly, allowing its pilots to trust it. "It's like a Cadillac and a Ford," Mike said, trying to compare the F6F with the SB2C, "or maybe I ought to say a Cadillac and a Mack truck!"

The task group had a schedule to keep, as usual, so Micheel's training period was abbreviated. They flew formation, made a few gunnery passes; the next day they tried six to eight practice landings on the atoll's airfield. Training ended on the twenty-eighth when the word came from on high, probably from Jocko, "Now get aboard!" On the twenty-ninth, he and his men took off from the flattop to practice runs on a sled towed behind the ship. Mike made his first carrier landing in the F6F Hellcat, the 103rd carrier landing of his lifetime, that day. It was his fighter-bomber group's one and only practice landing.

Armed with four air groups, Hornet and her task group steamed for Peleliu. During the trip, Mike was asked to cut his team from twenty to thirteen pilots as the experiment evolved. The task group steamed nearly directly west, no longer circling south to avoid the enemy bases on Truk or Yap. On September 7, the air group commander decided a fighter sweep was unnecessary. At 0531 with the island bearing 331 degrees, at a distance of eighty miles, Hornet set up a huge strike of fighters, then fighter-bombers, then torpedo planes and a deckload of SB2Cs. The eight Hellcats of Lieutenant Micheel's strike carried the same load as SB2Cs carried, only they leapt off the flight deck and charged into the sky. Strike groups from two other carrier squadrons rendezvoused with them. The big formation made visual contact at 7:05 a.m. Aircraft from Wasp went first while Air Group Two circled east of the island. From his vantage point, Micheel could see that the enemy AA flak had dropped off considerably since the last time he had sortied for Peleliu.

The strictures about radio silence had long since lapsed. Micheel got a call when the other squadron completed its mission and his wing was on deck. He brought his Hellcats around from the north, increasing speed as he nosed down to nine thousand feet before breaking into a seventy- degree dive. He and the two planes on his wing pointed their bombs at an AA battery on the tip of the small island a stone's throw from Peleliu called Ngesebus. As he fell below three thousand feet at 430 knots indicated airspeed, Mike would have noticed the small bridge that connected the two islands as he released the bomb. He pulled out at two thousand feet and felt the F6F roar back skyward. The new antiblackout suits made it a lot easier to withstand the terrific g-force experienced in a pullout. In front of him the SB2Cs of Bombing Two were hitting the main island of Peleliu. Behind him and his wingmen the other fighter-bombers aimed for revetments and bunkers around the airfield on Ngesebus. Micheel's team rendezvoused with the others two miles east of the target and all returned. In the reports on their missions all of the air group pilots admitted they could not discern the amount of damage they had inflicted on their targets. Peleliu and Ngesebus "appeared to be badly damaged by previous attacks."

The afternoon strikes took off to hit Angaur, the most southern of the Palau chain, which also had an airfield. The pilots of Bombing Two reported that their new SB2Cs, the dash threes, performed better than the SB2C-2s. The task group retired to the east that night, the standard procedure to make a night attack difficult for enemy aircraft. The only bogeys, though, turned out to be friendlies. The next day, September 8, while the squadrons made a few more strikes just for good measure, Admiral Clark's task group continued west, bound for the island of Mindanao, in the Philippines. The destroyers and battlewagons, which had been escorting the flattops for months, took the opportunity to surround Peleliu and shell every target on their maps.

THE 1ST MARINE DIVISION AND THE REGIMENTAL COMBAT TEAM (RCT) OF the 81st Infantry Division--together the Third Amphibious Corps--conducted its practice landings on Guadalcanal on August 27 through 29. Carrier air support, naval gunfire (NGF), and all the amphibious craft delivered the punch that General Rupertus intended on the western end of the famous island. The exercises went well. Afterward, the marines were allowed to visit the big military base and its PX, which offered all sorts of delights.194 Few of them had ever been to Guadalcanal before, but by 1944 the women of the Red Cross had been stationed there for almost a year.195 Most marine units passed through the Canal on their way somewhere else. Burgin got to the PX and managed to eat a handful of ice-cream bars.

The fun ended on September 4, when the 3/5 boarded their LSTs and steamed northeast toward Peleliu through several days of rain. The LSTs, called Large Slow Targets for a reason, departed first; the other ships would catch them easily en route. Sledge's LST 661 had a Landing Craft Tank lashed on the weather deck, as well as two large pontoons used for making a floating dock after the assault. The 661 would become the LVT repair ship after discharging its cargo, so a large crane and piles of maintenance equipment left little free space. Below the main deck, on either side of the big hold filled with the amtracs, were two long aisles filled with metal bunks where King Company slept. An LST had the flat bottom of an amphibious craft, giving it the seagoing stability of a cork. Luckily the rain and heavy seas cleared on September 7. The men at the point of the Third Amphibious Corps sailed through twenty-one hundred miles of calm ocean ahead of schedule. Every day on the aft deck, Sergeant Pop Haney conducted his one-man bayonet drill.196

LIEUTENANT COLONEL SHOFNER LOOKED FORWARD TO COMBAT. HE WOULD LEAD a massive offensive. Its destructive power exceeded what he had endured on Corregidor. Although his troops were not landing on Mindanao, Shifty could take comfort that this assault marked the opening salvo of the invasion of Mindanao, scheduled for mid-October. The POWs at the Davao Penal Colony would soon be free. Shofner's state of mind did not come across as ferociousness to his regimental CO, Bucky Harris, though. Harris could see his 3/5 commander making every effort to succeed, but a high level of irritability seemed to be affecting his leadership.

THE FINAL DAY OF SID PHILLIPS'S ONE- MONTH LEAVE IN MOBILE HAD COME quickly. He had spent a lot of time with his friends, enjoying every moment, every glass of clean water, every moment in a dry bed with clean sheets. Dr. and Mrs. Sledge had loaned him Gene's car. Dr. Sledge used it for bird hunting, so it smelled like wet dog. Sid had driven it down to the courthouse, "took the drivers test, told the policeman a bunch of war stories, and drove away with a driver's license." The good doctor had kindly left it with a full tank, which meant a lot since gasoline was still rationed.

The last day of his leave found him and his friend George strolling through the Merchant's Bank. George stopped to say hello to one of the tellers. Sid recognized her immediately. Her name was Mary Houston. "I nearly collapsed right on the floor." It had been years since he had seen her in Murphy High School and he had just assumed she had married. "She was even prettier than I remembered." Sid walked out of the bank kicking himself for drinking beer with the boys on the Gulf while he could have been trying to make time with Mary Houston. He boarded a bus the next day, bound for his next duty station: the Naval Air Station at Boca Chica, Florida. All the seats were filled. Private First Class Phillips stood in the bus's center aisle for twenty-four hours.

BY TRUCK AND BY TRAIN, SERGEANT BASILONE'S 1/27 DEPARTED HILO FOR THEIR camp. The old salts knew they were approaching their new base when their vehicles exited the lush rain forest and entered a high desert. Of course Camp Tarawa, named by the 2nd Marine Division, had been built in the desert, a dozen miles from the sea. The wind blew reddish volcanic ash against a few buildings, a few Quonset huts, and a great sea of eight-man tents.197 Leave it to the Marine Corps to find the ugliest part of Hawaii. "No wonder," said one wag, "the 2nd Division was so happy to invade Saipan. . . ."198 The Twenty-sixth Regiment had arrived first and taken the best part of the camp. The Twenty-seventh Regiment at least got the second choice and left the hindquarter to the Twenty-eighth.

John wrote his family, who must have been astonished to see that he was keeping his promise to write often. "Dearest Mother and Dad and all," he told them, "I'm back in the South West Pacific." After inquiring after everyone's health, he asked, "Have you heard from my wife, I sure wish she can get time off and come to see you all. For she sure [would] love to go to Raritan and see you all. How do you like our wedding picture." He hoped to get to see his brother George, whose 4th Division was also stationed in the Hawaiian Islands. "Mom you should see me now I got all my hair cut off and am getting black as a negro." The gunny, his buddies Clint, Ed, and Rinaldo, and the machine gunners in his section had also shaved their heads bald, on a lark.199 John wasn't sure what he could write that would get past the censor. "It is a beautiful place its hot in the days and cold in the nights." He sent them all hugs and kisses and "Don't forget," he signed off, to write him soon and to send one "also to my wife."200

TASK FORCE 38 HAD ROAMED AT WILL ALONG THE PHILIPPINE COAST. ITS ATTACKS on Mindanao, which began September 9, had met little resistance, much to everyone's surprise.201 Air Group Two shot up the small ships they found in Davao Harbor and ignited the planes they found parked on the airfields near the city. Although six days had been scheduled, Mindanao took only two. Up the island chain the fleet steamed, hitting Leyte and waiting for the Japanese to respond. Micheel led his fighter-bombers across Leyte to the island of Negros, on the western side of the Philippines. While his group strafed a sampan, Micheel spotted two enemy fighters and went after them. He made several gunnery passes, but they escaped. The squadrons of Air Group Two saw more planes lining the runways than they encountered in the sky. On September 12, one of the fighter pilots went down near the island of Leyte. He arrived back aboard Hornet the same day; having made it to shore in his rubber boat, he had been picked up by guerrillas. The guerrillas had contacted the fleet and had him home by lunchtime.

The returned pilot, Ensign Thomas Tillar, brought with him news from the locals that the Japanese airfields of Leyte had been emptied. His report confirmed the experience of the pilots thus far. The war was not here. Admiral Clark sent Tillar's report on to the new carrier commander, Admiral Bill Halsey.ab The wolves kept up the chase. Lieutenant Micheel made a run in an SB2C that same day, diving through some "meager" AA fire to destroy four planes he spotted on Saravia Airfield on Negros Island. Upon his return, Mike brought his plane around the end of Hornet, took the cut, and caught a wire. The wire pulled the tail hook off, sending the SB2C into the crash barrier. The spinning prop tore itself into pieces as deckhands dove for cover. It was the last time Mike flew the Beast.

The odd enemy plane came within the ship's radar as Hornet steamed south. On September 14, Micheel's fighter-bomber group met in the ready room before five thirty a.m. to get their assignment. "With Davao bearing 284deg, 112 miles," Strike 1 would launch at six a.m. A solid wall of clouds blocked the sky at thirteen thousand feet. At five thousand feet they could get good visibility. The leader of the fighter sweep, a few minutes ahead of Micheel's group and Buell's SB2Cs, radioed that he had spotted an enemy destroyer in the gulf outside the harbor of Davao. Micheel, behind Buell, watched him break his eleven Helldivers to port. As he approached Davao, he saw Buell's wing coming north, toward them. While Mike's team circled, Buell scored a direct hit on the destroyer. Others followed. The destroyer threw up a fair amount of AA fire, but to no effect. The Beasts blew the aft portion of the ship off, and then it "settled rapidly by the stern, disappearing under the water, bow last, inside of two to three minutes. . . ."202 Mike and his comrades worked over the airfield, looking for revetments hiding aircraft or storage tanks. He took them out over the gulf, where Buell's team were circling over the oil slick--all that was left of the IJN destroyer--and they turned toward Hornet. Later, the skipper would lead in another strike, just to make sure the enemy knew: the port of Davao was now closed. Mindanao had been cut off from the Empire of Japan.

SOMEWHERE OUT OF SIGHT BUT CLOSE BY, SIX ESCORT CARRIERS STEAMED, providing security to the Shofner Group. Lieutenant Colonel Shofner's marines would have lots of close air support. Another four of the navy's smaller carriers waited for them off Peleliu. These carriers, operating with five battleships, four cruisers, and fourteen destroyers, had begun plastering Peleliu on September 12. On D-day minus 1, or September 14, the LSTs neared the target. The troop transports, which had left the Canal well after them, caught up. Shofner and the other officers opened a sealed letter from the commanding officer of the 1st Marine Division. In it, General Rupertus informed his troops that the battle for Peleliu would be "extremely tough but short, not more than four days." While this message was delivered to all of the marines, men at Shofner's level would have heard another bit of good news. The big navy guns providing the preinvasion bombardment (NGF) had begun to run out of targets. It was a welcome change from the last report received before departing Pavuvu: aerial photographic reconnaissance had spotted tank tracks up near the airport. The division's tanks had been shifted north, out of Shofner's immediate zone of operations.

ON AND OFF DURING THE TRIP, EUGENE SLEDGE HAD TRIED TO READ HIS NEW book, River Out of Eden, about a boy's adventure traveling up the Mississippi River on a flatboat. On D-day minus 1, though, he wrote some V-mails. He wrote Sid, thanking him for the photos of Spanish Fort and continuing to make plans for their trip after the war to visit Civil War battlefields. Gene also described the scene around him on the weather deck: groups of card players crowded every corner. The sergeants of King Company stepped over and around the bodies, bellowing orders that seemed to always begin with "You people!"203 Gene's description made it by the censor easily, even though it informed Private First Class Phillips that his friend Ugin would soon be in harm's way.

Eugene also wrote his parents a letter, one much shorter than his usual. He never once betrayed any hint of where he was or what the next day held. Most of it consisted of a continuation of his Christmas wish list, since his parents would purchase his gifts early in an attempt to mail them in time. He reminded his mother of their trip to New Orleans, the memory of it a treasure to him. As dusk gave way to darkness, few men moved below to sleep. The cool breeze on deck provided some relief from the heat. Those who could not sleep could pace. The low baritone hum of the engines had been forgotten about until they switched off. The quiet felt sudden and ominous.204

ON SEPTEMBER 14, JOHN BASILONE "PULLED RANK." WHEN HE FOUND OUT THAT there was a fair amount of air traffic between his base on Hawaii and his brother's base on Maui, he requested a ride.205 John flew over to see George, who was training with the 4th Division. They had last seen one another in August 1943. George had participated in the invasion of Kwajalein, in the Marshall Islands, and in the invasion of Saipan, in the Marianas. Unlike John, though, George did not serve in a rifle company.206 He handled supplies. John sent both his mother and his wife a photo of him and George. Dora Basilone allowed the newspaper to use her copy of the photo in a small news item entitled "Basilones Meet in the Pacific."

AFTER BREAKFAST, MORE THAN A FEW K/3/5 MEN CLIMBED A LADDER TOPSIDE. They watched the sun rise behind Peleliu, framing the dark little island, and shining into their eyes. With each passing moment the volume of the bombardment grew. The great thundering cannons of the battleships punctuated the faster, point-blank shooting of the destroyers and the angry buzz of the navy planes on their bombing runs. The staccato blended into a vast storm. Each marine told himself that this violence was a good thing. No enemy could survive such fury. The island disappeared inside a dark pall of smoke and debris, lit by fires churning underneath. Apprehension grew inside them. It was all so big, so far beyond the power of the individual. "Everybody belowdeck." 207 Noticing that some of the new men in his squad seemed nervous, Burgin told them, "Just keep your calm and everything will turn out all right. Just do your job."

Down the ladder and into the metal cavern of the LST, the men of King Company found their thirteen amtracs.208 The engines' exhaust fouled the air. The three nearest the bow door had a cannon mounted on them. The next four LVTs were newer models with rear ramps; these also carried King's 37mm antitank guns. The marines in the six remaining amtracs had to climb up the sides to get in. Sledge's #2 gun squad was assigned LVT 13. It would be in the second wave of amtracs carrying troops. A light opened at the far end of the chamber. The engines gunned, and one by one they drove out toward daylight.

After their craft splashed into the ocean, the heads of the mortarmen were about the height of sea level. Everything loomed above them. Swabbies in T-shirts took in the scene with keen interest, a cup of coffee in one hand.209 A few waved cheerfully at the helmeted figures below. The other three LSTs of the 3rd Battalion lay at anchor nearby, disgorging assault craft as well. The amtracs churned slowly toward their positions. Inside the assault craft, the noise of bombardment began to separate the men. Only by yelling in a man's ear could Sledge communicate. Snafu offered Sledge a cigarette. Sledge said he did not smoke. To which Snafu replied, "You will."210 Burgin laughed.

SHOFNER CLIMBED INTO HIS AMTRAC TO RIDE IN WITH WAVE THREE, OR THE second troop wave. Once in the water, he could not see much, but all seemed to be well. The NGF had begun firing precisely at five thirty a.m. and continued to fire shells over his head. The calm sea stirred with each titanic broadside of the battleships, as the recoil rocked the ship and created a wave. At 0800, the circle of assault LVTs broke, fanned out into a line, and started toward the beach.211 The small circle of wave two followed and then his own trip began.

THE FIRST QUESTIONS THAT CAME TO SLEDGE'S MIND WERE "WOULD I DO MY duty or be a coward? Could I kill?"212 The salvos of the big guns and their attendant concussions isolated each man. It was so loud, so intense, Sledge could hardly think. "Would I ever see my family again?" The great forces unleashed the first flush of panic at the thought of being tiny and vulnerable amid the unforgiving steel. Sledge's amtrac came to the coral reef and began to crawl over it.213 The engine stalled. A few moments passed. Explosions sent geysers of water in the air nearby--the enemy was shooting back. The powerful fear it awakened within him surprised him: "you wonder why someone wouldn't have thought of it sooner . . . for the first time I thought, My God, that metal will absolutely tear through somebody's flesh." He went weak from fear and braced himself against the side of the tractor. Terror, frantic and certain, gripped him so hard, he thought, "I might wet my pants."214 The engine came to life. Up and over the reef they went. Peeking over the rim, the mortarmen could see amtracs had been hit and were burning. Eugene "saw several amtracs get hit and it was just awful because Marines just got blown into the air and some of the amtracs burst into flame . . . I found solace in just cussing the Japs."215 Individual marines were bobbing in the water, struggling to get to shore. Fires burned onshore, roiling beneath a tall cliff of black smoke. The sight of it made the eyes of the combat veterans, like Burgin, grow wide. This was a new level of danger. Burgin said to himself, "God, take care of me, I'm yours." A stream of bullets smacked into the front of the craft. Someone yelled, "Keep your heads down or they'll get blown off."

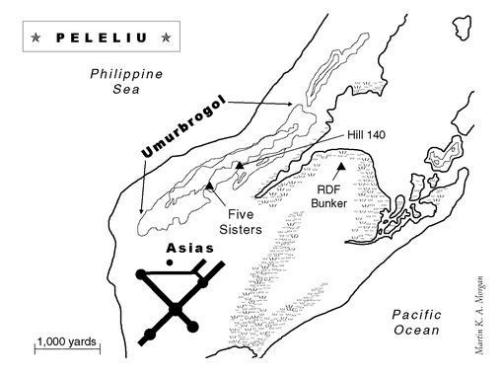

THE TWO WAVES OF AMTRACS AHEAD OF SHOFNER HAD BEGUN TO BUNCH UP. Inside the reef, large "coral boulders" combined with some man-made obstacles narrowed the open tidal area into a few avenues of approach. Most of the amtracs crowded into the free lanes as others bellied up on the coral boulders and became stuck.216 Nearing shore, they came under fire from a 47mm antiboat gun firing from a tiny islet jutting out from shore to their right.217 The ships' batteries could not hit it because it was located behind the islet, and the carrier planes above could not see it. Its fire devastated the fleet of amtracs using beaches Orange Two and Orange Three.

THE AMTRAC CRAWLED OUT OF THE WATER AND STOPPED. SLEDGE HEARD, "HIT the beach!"218 The mortar squad clambered over the side of their LVT. He followed Snafu, but lost his footing and landed on the beach in a heap. Every shell, every white stream of machine-gun bullets seemed to be aimed directly at them. Although the beach was white and smooth, it consisted not of sand but of hard coral. The burdens of his rifle, apron of 60mm mortar shells, and personal equipment became ungainly in the storm and Gene struggled to catch up with the squad. Strands of barbed wire, attached to metal stakes, crisscrossed the area, preventing men from crawling.

Across the strip of white coral he came to a shelf of vegetation, most of which was burning or had been burnt. Sledge nearly stepped on a land mine. He noted the inches separating his foot from the triggering plate. He looked up and saw a marine step on one "and he just atomized, just disappeared." Inside the copse of coconut trees, broken and angular, the men of King Company ran into the tank trap.219 The depth kept them out of the line of fire. One of King's sergeants, Hank Boyes, noticed "everyone was very content to stay there in what seemed a safe spot."220 Bullets passed over their heads. Gene said, "Burgin, give me a cigarette."

"Gene, you don't smoke."

"Give me a cigarette." Burgin handed him one. Gene "took it and I looked at him, and he had it between his lips. I looked back a few seconds later and he was chewing it, that's how nervous he was." Burgin saw Sledge's eyes "bugged out" and told him not to pay too much attention to the bullets snapping overhead. "Like hell," Gene said, "those are real bullets."221

THE CO OF 3RD BATTALION LANDED AND FOUND A LOT OF MARINES WAITING FOR other marines to move forward. Shofner stood up and yelled, "Come on, there's not a Jap alive on the island!"222 He ran forward to a shell hole twenty-five yards in from the shore. He had his carbine, map case, and a radioman.223 He tried to get a handle on the situation. Item Company had moved inland. His other company, King, was confused. His junior officers were struggling to get their men organized. The noise made verbal communication all but impossible. All of their training in small-unit tactics relied on the integrity of the squads and platoons. Time passed. Part of one platoon came in from the left, where Item had landed.224 After fifteen minutes, they identified the holdup. The antiboat gun off to their right had driven amtracs of the Seventh Marines onto Shofner's section of beach. Worse, the unit of the Seventh that had landed with them was King Company, 3rd Battalion. Two King Companies were struggling to get their men sorted out. The amtrac containing Shofner's communications equipment was hit. Some of the men swam ashore, but without the bulky machinery. Just as Shofner's platoons prepared to move out, the enemy mortars began exploding all around them. A shell killed Shofner's executive officer. Movement in King's area of the beach stopped. The last of Item, to the left, moved out.

The barrage lasted thirty minutes. The drive inland began when it lifted. Shofner pushed forward to an antitank trench and established the 3/5's command post, although, without a powerful radio, his knowledge of and control over events became limited. The radio carried by his assistant might reach his company commanders, the colonel leading the 1/5, or even the regiment, or it might not. He needed runners. His wrote a message and gave it to a runner to give to division CP: "3/5 progressing in tight contact with" the Seventh Marines. "Urgently require communication personnel," and "Request latest in progress" of First Marines.225 Some updates reached him. Item Company had attained its objective and was tied in with the 1/5, to his left. The 1/5 had halted because the unit on its left, the First Marines, had been halted by fierce resistance. To Shofner's right, King Company had begun to push forward.

THE NEXT PUSH OF KING TOOK IT OUT OF THE DITCH AND THROUGH THE SCRUB. To one of the riflemen, it did not look like anybody "knew where they were going. It was just: jump in a hole, stay there, and look at everybody else. If they moved, you moved."226 The dense thickets kept visibility low. The cannonading continued around them. The mortarmen carried their rifles at the ready, waiting to meet the enemy, trying to keep together in the tangle of dense brush. They came upon the skirmish line of the riflemen, who had stopped at the edge of the vast clearing that held the airfield.227 A number of pillboxes barred the way. Sergeant Hank Boyes was yelling for his men to shift their line of advance to the right. King was not tied in with the 3/7 on its right and the gap was dangerous.228

SHOFNER "WAS TORN BETWEEN HIS REQUIREMENTS TO MAINTAIN CONTACT WITH his higher headquarters, the Fifth Marines, and his need to keep his rifle companies in a coordinated effort against a possible Japanese counterattack." Love Company landed and he sent it to cover a gap emerging between Item on the left and King on the right. His battalion was at last pushing inland. Shofner may have heard that half of the tanks had been hit before they reached the shore. The 2/5, the last of the regiment's three battalions to land, began arriving just before ten a.m. It began to march into the gap between the 1/5 on the far left and Shofner's 3/5 on the right.

AT THE EDGE OF A GREAT OPEN PLAIN, CORPORAL BURGIN AND HIS #2 MORTAR squad had caught up to some riflemen. Burgin saw an enemy artillery piece near the airstrip. As he watched, the Japanese crew rotated positions every time the gun fired. It seemed odd that each man had to take a turn hefting ammunition; there was no set gunner. Each of the crew exceeded six feet in height, though, so they made good targets. Burgin got his men to start "picking them off one at a time." The attack began to gather steam and the push developed around to his right, where the field gave way to jungle. A marine tank appeared. It mistook King Company for the enemy and began to come at them. The #2 gun squad began to yell their unit name, but it seemed hopeless. The Sherman tank had no infantry around it to hear them.

Staring down the barrel of the Sherman's 75mm shocked everybody. One marine near it ran over to stop it. He was hit by something and fell. Sergeant Hank Boyes got around to the back of the tank, where the phone was. He jumped up on the back of the tank, which put him in an exposed position. The phone must have been broken. Most of King Company watched in amazement as he rode it like a cowboy. The enemy concentrated its fire on the most direct threat: Boyes's tank. Boyes directed the Sherman's fire at the artillery piece and three other pillboxes, the tank's 75mm shells penetrating inside and exploding each in turn.229 The assault continued to the right, away from the airfield and into the jungle.

WITH THE 2/5 TAKING OVER ON HIS LEFT FLANK, SHOFNER HAD PULLED ITEM Company off the left flank, brought it around the back of Love Company, and sent it forward to connect Love to King. He heard about King encountering some bunkers and called in an air strike.230 King had resumed the advance when Shofner received a radio message from the Seventh Marines on his right flank. The 3/7's CO said his "left flank unit was on a north-south trail about 200 yards ahead of 3/5's right flank element."231 The two officers agreed that the 3/7 would hold its position until King reached them. Shofner sent an order for Item and King to press forward.

A HUNDRED YARDS BROUGHT KING'S RIFLE SQUADS TO A LARGE TRAIL RUNNING perpendicular to their eastward advance. They halted there for a time. Captain Haldane needed to get connected to the units on either side of him. Item Company came up on his left. Both companies advanced across the trail and eastward again through the brush.232 King Company's first platoon halted before noon, when they could see water ahead of them. They had nearly crossed the island. The other parts of the company caught up as an hour passed. No one had contact with the battalion CP.233 The water levels in the two canteens of water each man carried began to get low. The heat and the physical exertion made each man in #2 mortar "wringing wet with sweat."234 They prepared to defend themselves from a counterattack.

ABOUT THREE P.M., SHOFNER DID NOT KNOW EXACTLY WHERE HIS KING COMPANY was, but he heard where it wasn't. The 3/7's CO radioed Shofner that "the position of 3/7's left- wing unit had been given incorrectly."235 It had not advanced as far as he had told Shofner earlier. His unit was not in contact with Shofner's King. That meant that the 3/5's assault teams were well out in front of the entire division's front line, exposed on both flanks to enemy attack. When he understood the situation, Shofner ordered Company K to bend its right flank back in an effort to tie in with the 3/7. He had also become worried about Item, in the center of his line. Love Company, on his left, was fine: in touch with its flank, the Fifth Marines, and making steady progress across the airfield.

BURGIN HAD SLEDGE AND SNAFU SET UP THE GUN ON THE FAR SIDE OF THE VAST open plain that held the airstrip. They found a crater for their gun position. "Snafu put the gun down, flipped the buckle on the strap, opened the bipod out, stretched the legs out, tightened them up, snapped the sight on." A simple device, the sight had two bubbles that were leveled for elevation and windage. Snafu "took a quick compass reading on an area that they told us to fire on and we put a stake out there at the edge of this crater."236 The order came to fire. Snafu looked at the range card that stated the number of increments. Sledge "repeated the range and pulled off the right number of increments to leave on the correct number, pulled the safety wire and held the shell up" with his left hand. The thumb on the left hand held down the shell's firing pin. When he let it go, it slid down the tube, hit the bottom, and discharged with a soft hollow whisper. The order came to cease fire or secure. The mortar team waited. The heat was crushing. The old salts predicted the enemy "would pull a banzai tonight and try to push us off the island. We'll tear 'em up."237

Sledge looked north, across the great distance of the airfield. He saw some vehicles moving amid the explosions. "What are all those amtracs doing out there next to the jap lines?"

"Hey, you idiot," Snafu replied, "those are jap tanks." Sledge felt his heart nearly stop at the thought of enemy tanks.238

AS LATE AS FIVE P.M., SHOFNER WAS STILL STRUGGLING WITH A FAULTY COMMUNICATIONS network to get his men tied in properly. The communications officer of the Fifth Regiment arrived. The two began to sort out a solution when a mortar shell exploded near them. Shofner's "mouth was dry and his breath was short, he had no feeling in his left arm and he looked down and could see the bones of his forearm, the skin and muscle torn away by shrapnel. He looked up and tried to speak but there is no one to speak to. Then as if in slow motion, he saw Marines from the adjacent units spill over into the shell crater. He heard the cry for Corpsman, and he heard some Marine yell that 'the damned japs had got Shifty.' Then things went black."

He awoke on a stretcher, being carried across the beach and onto a Higgins boat. His arm had been bandaged and he was receiving plasma. Shofner "tried to protest, but his head was in a cloud, and he suspected he [had] received a shot of morphine." A marine said, "Don't worry, Mac. You be OK." Unconsciousness slipped over Shifty again. When his eyes opened again, he saw he was lying in the cavernous amtrac deck of an LST. His head ached badly. He "felt the sheets under him. He was naked except for his bed linen. His left arm throbbed." The navy's medical teams moved quickly to handle a lot of wounded men. A corpsman noticed he had awakened and called over to his supervisor, "Well, Colonel Shofner, you are a lucky man"; he would make a full recovery. Austin wanted to know what had happened and was told he "was the sole survivor of his command group." Colonel Shofner asked about returning to his unit. The corpsman "became evasive and suggested that he rest for a while."

THE ENEMY TANKS NEVER GOT VERY FAR SOUTH. THE GREAT WHITE AIRFIELD AND the plain that encompassed it were mostly empty. Although the sound of the big guns filled the air, Sledge and his mortar team were threatened mostly by small-arms fire. With his rifle platoons already committed, King Company's skipper, Captain Haldane, ordered his headquarters personnel to help tie his line in with the Seventh Marines, but to no avail. The skipper ordered his company into a perimeter defense. The hard white coral could not be dug out by hand. Marines picked up what chunks of coral they could to provide some small cover for their bodies. Darkness found King Company still in an exposed position, still not tied in with either the left or the right, but ready to hold their ground.239 The big fear was a banzai attack. King had strung its barbed wire, the mortars and machine guns had registered sound rounds, and Captain Haldane had a telephone line back to the artillery. As far as Eugene Sledge could tell, though, "we were alone and confused in the middle of a rumbling chaos with snipers everywhere and with no contact with any other units. I thought all of us would be lost."240

The small-arms fire slackened as it grew dark. After a couple hours, the word came to pack up, King was pulling back. Battalion wanted it tied in with Item on the left and the unit of the Seventh on the right before the banzai began. Stumbling in the dark through the wild thickets and scrub jungle along the edge of the field made for a lot of cursing, but they moved close enough to the right spot to be allowed to dig in.241

Although not properly tied in with Item, Love Company, or the Seventh Marines, King Company marines began to string barbed wire along the edge of the airfield to hold off the banzai attack.242 The sound of howitzers and the naval gunfire and heavy mortars and machine guns continued all night long. Much of it emanated from the north end of the airfield and from the ships offshore, although enemy mortars rained on the beach. The navy ships also fired huge flares, which swung slowly in the sky as they fell, skittering shadows across a broken and burning landscape.243 The marines of the #2 gun squad piled rocks around themselves and slid into shell holes to get below the line of fire. In the darkness, Sledge took off his boots because his feet were sloshing in his sweat. Snafu yelled, "What the hell you doing, you better get those damn boots back on . . . By God, you don't never know when you're going to have to take off [running]."244 Lying nearby, Burgin laughed as Snafu cursed the new guy for being "a stupid son of a bitch." Corporal Burgin expected the enemy charge to come, just like on Gloucester. He worried about the dwindling levels of water in his squad's canteens and began chewing on a salt tablet.

In the early hours of September 16, Burgin was proved right: a charge did come. A ferocious concentration of machine-gun fire on his left, the guns of the 2/5, knocked down the dark shapes of running men.245 The #2 gun shot up a lot of illumination rounds, each lasting about thirty seconds. With a few flares hanging up there, it was light enough to see that no hordes of Japanese were running at King. The cacophony of hard fighting continued on both sides of them.

When dawn broke, those still trying to sleep had to abandon it. The canteens of Burgin's mortar crew were empty. The support teams brought up water in five- gallon cans and fifty-gallon drums and everyone was mad to get it. The first sip brought a nasty shock to the #2 gun. It tasted like diesel. Some of the guys around them drank it anyway. Burgin joked that he could blow on a match and be a flamethrower. Stomach cramps followed and a few puked. As usual, though, a trooper's fate hung in the luck of the draw. Other squads in King Company received two canteens of clean water.246

The task facing them was to cross the airfield. It looked like a long way. Burgin guessed it was over three hundred yards. At the signal, the skirmish lines of marines ran out into the open field and across the hard white coral runway. The Japanese unleashed a barrage upon them as expected. Large shells, mortars, and machine- gun bullets cut the air around them as the marines ran east for all they were worth. Much of the enemy's fire came from its positions on the northern end of the airfield, to King's left. Most of their regiment and all of the First Marines, therefore, stood between King and the guns. Love Company ran on their immediate left. Every step felt like their last. As he ran, Gene "was reciting the 23 Psalm and Snafu was right next to me and I couldn't hear what he was saying, but most of it was cussing."247 Burgin watched the white tracers flash past him until he found cover on the far side. "I don't know how we didn't all get killed--I really don't."248 No one else did either.

The thick scrub they entered slowed their progress toward the ocean, but resistance was light. They came to a wild thicket of mangrove swamp that marked the shoreline. King tied in with the Seventh Marines on their right. The Seventh had its hands full with securing the southern tip of the island. To their left, farther north along the eastern shore, Love Company tied in with them. Item Company, the other component of the 3/5, marched still farther north. King Company dug in as ordered, out of sight and away from the battle.249

With time to catch his breath and reflect, Sledge realized the last thirty-six hours had been "the defining moment in my life."250 Much of what he thought he knew--from the Civil War books he had read to the "Barrack-Room Ballads" he had memorized--had had nothing to do with the carnage, the chaos, the electric fear threatening to engulf him. Gene had watched a wounded marine die and was aghast at the waste and inhumanity. He had watched two marines pluck souvenirs from two dead Japanese and wondered whether the war would "dehumanize me." He needed to process these experiences. He felt a duty to document his battle for his family, so they would know what the future books about Peleliu left out. Eugene B. Sledge decided to write himself notes in his pocket Bible so that he would not forget the horrors he witnessed.251 "The attack across Peleliu's airfield," E. B. Sledge later wrote from those notes, "was the worst combat experience I had during the entire war."252

He had seen marines fall during his run across the airfield, even though he had tried to look straight ahead as he ran. The number of wounded went uncounted because the invasion day's tally and the fierce battle the First Marines were having up north had overwhelmed the system.ac One marine had been killed for sure, though. Private First Class Robert Oswalt, Gene's friend, had been hit in the head by a bullet or a fragment from a shell.

The big guns found King's position before dark. Burgin lay on his stomach, hugging the earth and listening to the quick swishing noises and feeling the concussions. He thought those shells were so big he could see them. Chunks of coral, mud, and mangrove splattered down upon the men of #2 gun. The size of the explosions left them sick with fear. A line of communication wire had been tied to a phone in Burgin's foxhole. It connected him to the other platoons, Haldane's company CP, and from there further back to battalion. Burgin got on the phone, heard someone answer (he wasn't sure who), and reported that his position was taking friendly fire. He heard the man reply, "No, that's not ours--that's jap."

"No, that's ours," Burgin replied, and began cursing. "I know where we just came from, and that artillery is coming where we've already been, so I know it's ours. So get it ceased." The other marine remained unconvinced. Burgin could tell the shells were 155s and yelled, "If you're going to fire . . . go out a little further than that because you're going to kill my whole damn bunch."253 The barrage increased and worsened. Shells burst about twenty or thirty feet above the ground, sending searing shards of metal down upon them. King had had almost no cover. They could only hold on and wait till it ended.

As the shelling, both U.S. and Japanese, slackened, the marines tried to get water. Some found a grayish liquid in the bottom of some of the deeper shell holes--the water table was very high on Peleliu. The men who drank it became sick, even the ones who strained out the big particles by keeping their teeth closed. In the mortar squads, Stepnowski, a big guy from Georgia they called Ski, dropped out. The heat and the dehydration were too much. He was turned over to the medics, who took him back. Lack of water caused one-third of the casualties.254 Sledge noted that the big men tended to give in to heat exhaustion more often than those of slighter build. The day ended with stringing barbed wire in preparation for a banzai attack.

When the night passed without an attack, King Company had so far gotten off easier than others and some of them knew it--not E. B. Sledge, however. The dead and wounded men he had seen and the punishing concussions of high explosives left him terrified. He hung on gamely, lugging mortar shells and preparing to fire the #2 gun. During the next day, they watched as the ridge to the north took a horrendous pounding from the ships' guns, from navy planes, and from the howitzers of the Eleventh Marines. King marched toward the ridge that morning, behind the rest of the 3/5. Along the east side of the airfield, they saw millions of jagged shards of metal-- shrapnel--covering it.255 The wreckage of airplanes included more than two dozen medium bombers and dozens of fighters.256 King arrived at the junction of the cross runway. Item Company dug in there, inexplicably, while Love and King closed with the village that draped around the north end of the airfield. The volume of small-arms fire picked up precipitously. They were not on the front line yet, though. The 2/5 was ahead of them and, beyond them, units of the First Marines.257

King soon moved along the eastern edge of a mad jumble of craters, airstrip, and demolished buildings. Most buildings were farther west, on their left. Love Company was over there, tied in with units of the First Marines, in the thick of the fighting by the sounds of it. Item Company remained behind them. By the end of the day, #2 gun had advanced through the small collection of buildings to a point where they could see the northern ridges. King tied in with elements of the 2/5.258 To their left, west, were the ridges; to the north and to the east, roads led into terra incognita. They watched the other units attempt to move north. "Anytime anybody got up, the Japanese started throwing not just machine- gun or rifle fire, but shell fire."259 Watching it happen, Gene could not see the enemy positions, only a riot of confusion, fear, and pain. The Japanese fired so many weapons, the coral ridges were so impregnable, he thought, "we had absolutely hit a stone wall." The soft malice of the incoming mortar rounds sounded to him like "some goulish witch telling you that 'Well, I may not get you this time, but I'll get you next time.' " The sound of combat never ceased that night, although the enemy again failed to mount a banzai charge. Burgin began to think "there was something up. They were fighting with different tactics altogether."

The next day, the third day of the "three-day campaign," as someone surely noted, King moved east. The roads and buildings gave way to swamp. A small road crossed the marsh on a natural causeway of earth about a hundred yards in length. It widened into a clearing where the riflemen met some resistance. The #2 gun, along with marines from Item Company, ran across the narrow causeway and supported the assault on a small group of buildings in the larger clearing on the far side.260 The Japanese had abandoned most of their bivouac sites there, but there was a blockhouse with large antenna above it.261 King, supported by Item and elements of the 2/5, worked through the small-arms and mortar fire of the garrison and wiped out all resistance. King lost thirteen men wounded in action, its first day of double-digit loss.262 Nearly surrounded by thick mangrove swamp, King and Item dug in facing the only avenue toward solid ground and the enemy: south.

THREE DAYS HAD PASSED BEFORE LIEUTENANT COLONEL SHOFNER STEPPED back ashore on Peleliu. He did not know why they had held him for so long. A small neat bandage covered the wound on his arm.263 He set off to find the regimental headquarters of the Fifth Marines and report to Colonel "Bucky" Harris. No one would have been in a good mood at regimental HQ, and Shofner's first impression would have been that the battle was not going well at all. Losses were high and progress slow. Harris had been wounded in the knee by a shell that had burst in his CP, killing a man near him; he had refused evacuation and now walked with a painful limp. Bucky informed Shofner that he would not be returning to command 3rd Battalion. A major had been given the job and so far he was doing well. The colonel designated Lieutenant Colonel Shofner his regimental liaison officer with division HQ.

Shofner considered the liaison appointment a make-work job. As a colonel with access both to the regiment and the division, though, he was in a position to learn a lot about what was happening on the battlefield. There was a lot of bad news. The jungle canopy had obscured the terrain beneath it. The aerial reconnaissance photographs had shown a ridge north of the airfield; combat had revealed a much bigger problem.264 The bomb blasts and the engulfing flames of napalm had exposed an expanse of roughly five ugly, wartlike coral ridges, twisted and cut into a maze of peaks and gullies. The enemy had turned each of these myriad facets into a fortress, the coral escarpments riddled with pillboxes, caves, and nasty little spider holes.

Against this fortress Chesty Puller had driven his First Marine Regiment. The First Marines had always known that their mission was the toughest. Every day since D-day, Chesty had lashed his men, exhorting them to attack, to breach the defenses. His battalions had sustained horrendous casualties. The delay in cracking open the bastion just north of the airfield had angered Chesty's boss, General Rupertus. Rupertus's dour disposition had become nearly insufferable.265 He hobbled around division headquarters, pained by an ankle injury sustained a few weeks earlier, demanding results.266 The plan was for the Seventh Marines, who were finishing up their conquest of the southern tip of Peleliu, to support the First Marines' attack on the ridges. The Fifth Marines would continue to receive the easiest of the three assignments.

AFTER A QUIET NIGHT, KING COMPANY SPENT SEPTEMBER 19 MOVING SOUTH across another strip of land and onto another islet on the east side of Peleliu.267 A road ran through the open area bordered by mangrove swamps and dotted with a few buildings. On their left flank, Item got into a short firefight at a blockhouse. King faced almost no resistance.268 Behind them, the enemy's heavy artillery fire began to slacken. It also became harassing fire because it was obviously not targeted.269

The job of patrolling this confusing checkerboard of soil and swamp was not completed by the end of the day. The temperature relented, though, dropping into the high eighties.270 The next morning most of King Company walked out to still another islet, this one with a coastline on the Pacific, and set up camp on Purple Beach. Captain Haldane ordered a reinforced patrol; he joined Burgin's #2 gun, the war dog and his handler, and a machine- gunner squad to the riflemen of the First Platoon, their mission to search the southern tip of the larger islet behind Purple Beach.271 They moved out. Eugene eyed the war dog curiously because he loved dogs, but he had learned back on Pavuvu never to attempt to pet one.

The patrol went well during the day. They dug in near a lagoon in the late afternoon, the dense mangrove trees cutting visibility to a few feet. Another peninsula could be glimpsed on the far side of the cove. No one knew exactly how all of these pieces of land fit together. The word was there were fifteen hundred enemy troops over there. "We were there," as the #2 gun squad understood it, "to see that they didn't cross that lagoon while the tide was out." When someone reported hearing voices over there, the men began to wonder just when the tide went out. The vegetation rendered the 60mm mortar all but useless. Burgin took one last look before dark and concluded, "If the japs came across in mass swarms, they'd have killed every one of us."272 He had been with King Company during the Battle of Cape Gloucester, when it had held off a series of banzai attacks, but it had taken a lot more men and a lot more firepower to do it. They sat in the darkness waiting for the shit to hit the fan.

"It wasn't too long after dark this guy began to scream and holler." It horrified everyone. Even in the pitch-black darkness Burgin could tell the yelling came from the war dog handler because he was "within arm's reach." Orders to shut his mouth failed to stop his growing insanity. A medic found his way over and administered morphine. One shot made no effect. Burgin watched as "he gave him enough morphine to kill a horse. And it didn't affect him any more than if it had been water in the needle that he was using. And he went completely berserk, and he was hollering and screaming and he was giving our position away and, you know, that couldn't happen. And, uh, so he was killed with an entrenching tool that night, to shut him up." From the sound of it the crazed marine did not die immediately.

In the light of the next morning, it had to be faced. "One of their own" had been killed by one of their own. Most men concluded that it had had to happen. Burgin was grateful that he had not had to do it himself. Sergeant Hank Boyes called it "a terrifying night."273 No one spoke the name of the man who had wielded the entrenching tool. The lieutenant, a rifle platoon leader nicknamed Hillbilly, called Captain Haldane and "told him that he was bringing the troops in--he wasn't staying another night there." His small force could not hold off a force of that size."And so the company commander told him, 'Okay, bring them back.' So we come back and joined the company."274

King Company had set itself up on the northern tip of the islet called Purple Beach because it fronted the ocean, far from the battle but not far from infiltrating Japanese. Gunshots could be heard on an islet across the canebrake from them. The shots came from marines in Item Company, who cleared it out and came over to say they had killed "about 25 japs."275 That day, September 21, ended without any casualties in King. Its men had survived six days on Peleliu. Their thoughts might have been with their friends in Love Company, still attacking the ridges near the airfield, and also with the thirty-four wounded and four marines killed thus far.276 These figures did not include the war dog handler, since he had not been on King's muster roll, but they represented a hefty toll on the 240 men who were.

JUST AFTER FIVE A.M. ON SEPTEMBER 21 THE PHONES RANG IN THE STATEROOMS OF the wolves aboard the flattop USS Hornet. They assembled in the ready room to get their preflight briefing on their target: the city known as the Pearl of the Orient, Manila. The wolves were here to start the process by which the Filipinos and the American POWs would be liberated. With the city of Manila bearing 250 degrees and 142 miles away, the skipper led the first deckload of SB2Cs off the deck at seven fifty-nine a.m.277 Mike walked out to the flight deck at about eight thirty. The clouds and squalls of rain surrounding Hornet would add another challenge to the day's mission. No rear seat gunner met him. The Hellcat, clad in a dark navy blue with white roundels, had clean, angular lines, which contrasted sharply with the rounded forms of the Helldivers spotted on the stern. For the carrier's second strike of the day, twelve fighters took off first, then Lieutenant Micheel's six fighter-bombers, followed by twelve SB2Cs.

The sky cleared of mist as they arrived over Manila Bay. Campbell's earlier strike had left a fleet oiler of the IJN smoking badly and listing hard. It was just one of about fifteen ships out in the center of the vast natural harbor. Mike could see another ten ships inside the breakwater of Manila's port.ad Most of them looked small enough to qualify as interisland steamers, sampans, or boats. He focused on the most important ship, the destroyer. His fighter-bombers went first, the echelon rolling over into steep dives to avoid the canopy of flak with which the destroyer covered itself. The F6F could handle a steep dive. The destroyer turned too fast, though, and all six five-hundred-pound bombs missed. The SB2Cs made the second pass and also missed the "tin can." After their runs, the Helldivers joined up to return home, their gas tanks reading half empty.

Unlike the Beasts, though, the F6Fs had plenty of gasoline. They also had rockets under their wings. Mike set his men free to hunt for "targets of opportunity." Downtown Manila was off-limits and they ignored the island of Corregidor. Some of them went looking for airfields. Most followed Mike, racing along the shore of Manila. Japan's three- inch and five-inch AA guns emplaced along Dewey Boulevard threw up lots of flak, but they failed to so much as dent the fighter- bombers. With their rockets, Mike's wing of Hellcats set the small ships at the piers on fire. At the outskirts of the city, he triggered the six .50-caliber machine guns on "anything that looked like Army vehicles running down the road." He noted with satisfaction, as the others joined up on his wing, that "there wasn't much left."

Micheel landed back aboard in time for lunch. Two more strikes on Manila and its environs were launched off his flattop later that day. His friend Hal Buell took a turn.

The next morning began with bogeys flying toward their task group. Two raiders appeared on the radar screens just after five a.m. These faded from the screens after the CAP was routed out to meet them, and the first strikes against Manila took off. The bogeys kept coming, though, dancing in and out of the radar's range. Hornet began to lead her group in a series of course and speed changes as more enemy aircraft popped onto her radar screens. The Hellcats of the CAP reported "splashing" a few bogeys, but just before seven a.m. "two bomb explosions in the water on port bow, 225deg, 2700 yards," made everyone jumpy. Had the two bombs been jettisoned by a U.S. plane? No one could say for sure. Mike's flattop continued her evasive maneuvers, signaling its task group "to form cruising disposition 5V." Changing direction away from one bogey, though, sent it toward another, and she came about again. Fifteen minutes later, a bogey attacked Monterey, off Hornet's starboard quarter, dropping two bombs that landed a few hundred yards from her port- side bow.

Hornet signaled "for emergency speed 25, turn right to 300deg." The carrier came out of its left-hand turn and swung right (starboard) as she sped up. The port battery of AA opened up on a Zeke, or an enemy fighter, "diving from clouds 190deg relative, approximate range 4500'." The aft battery also fired as the bogey made a strafing run on the aft flight deck, the pilot matching his plane's 7.7 machine guns and 20mm cannon against Hornet's five-inch, 40mm, and 20mm guns. "The plane then made a sharp left turn and pulled up and away on port quarter." Its bullets had hit one of the carrier's gun tubes and left the wooden planking of the flight deck smoldering. The screening vessels continued to fire at the Zeke and the CAP vectored out after it. With her guns blazing at a second bogey, Mike's carrier continued her sharp turn until she almost collided with Wasp. As the captains evaded one another, Hornet's gunners opened fire "on Zeke on [the] port quarter bow outside of screen."278 Firing at an enemy plane off the far side of their destroyer screen meant they were jumpy. The bogey got away again. In the break, a lot of talk between the ships of the task group concerned AA guns firing too close to other ships of the group. The sky cleared enough for strike waves to be launched and recovered. Another wave of bogeys arrived around eleven a.m., though, and the flattop remained on high alert for the rest of the day, as the ship's gunners and her combat air patrol protected their carrier.

The task group steamed south that evening, away from the hive of bogeys it had encountered. The reaction to this retreat by Jocko Clark, who was on board as an advisor to the new task group commander but not empowered to make decisions, was to tell the new admiral he needed a better fighter director. The morning of the twenty-third began with preparations for more incoming bogeys. When the air remained clear, Hornet held funeral services for two crew members who had been killed by the strafing attack. The task group steamed south along the Philippine Islands. Micheel and the wolves flew a few more missions, and the fighter- bombers got credit for one clear hit and several near misses on a troop transport before the task group set course for the fleet anchorage. The anchorage had moved to a new harbor in the Admiralty Islands.