ACT I

"HOUSE OF CARDS"

December 1941-June 1942

AS THE 1930S GAVE WAY TO THE 1940S, THE PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES thought little of the Empire of Japan. Americans worried about their economy, which had wallowed on the brink of collapse for a decade, and wished to stay out of the world's problems. The speed at which Nazi Germany had come to dominate Europe had, however, provided President Franklin Roosevelt with enough political capital to take a few steps toward preparing the country to defend itself. Roosevelt and his military leadership also opposed the Japanese drive to dominate vast stretches of China. The Japanese government, ruled by a military cabal that included Emperor Hirohito, had created an ideology to justify its colonial conquest and built a military to enact it. Japan obviously intended to seize other valuable areas along the Pacific Rim. The United States controlled some of these valuable areas and it expected to keep the region open to trade. Roosevelt endeavored to curb Japan's expansion by a series of economic and diplomatic measures backed up by the U.S. military--the smallest and least-equipped force of any industrialized nation in the world.

FIRST LIEUTENANT AUSTIN SHOFNER WOKE UP EXPECTING ENEMY BOMBERS TO arrive overhead any second. Just after three a.m. his friend Hugh had burst into the cottage where he was sleeping on the floor and said, "Shof, Shof, wake up. I just got a message in from the CinCPAC saying that war with Japan is to be declared within the hour. I've gone through all the Officer of the Day's instructions, and there isn't a thing in there about what to do when war is declared."1 With the enemy's strike imminent, Lieutenant Shofner took the next logical step. "Go wake up the old man."

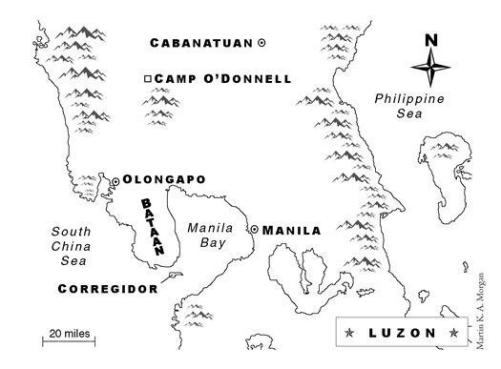

"Oh," Hugh replied, "I couldn't do that." Even groggy with sleep, Shofner understood his reluctance. The chain of command dictated that Lieutenant Hugh Nutter report to his battalion commander, not directly to the regimental commander. Speaking to a colonel in the Marine Corps was like speaking to God. The situation required it though. "You damn fool, get going, pass the buck up." At this Hugh took off running into the darkness surrounding the navy base on the Bataan Peninsula in the Philippines.

Shofner followed quickly, running down to the docks, where the enlisted men were billeted in an old warehouse. He saw Hugh stumble into a hole and fall, but he didn't stop to help. The whistle on the power station sounded. The sentry at the main gate began ringing the old ship's bell. The men were already awake and shouting when Shofner ran into the barracks and ordered them to fall out. The bugler sounded the Call to Arms. Someone ordered the lights kept off, so as not to give the enemy's planes a target.

His men needed a few minutes to get dressed and assembled. Shofner ran to find the cooks and get them preparing chow. Then he went to find his battalion commander. Beyond the run-down warehouse where his men bunked, away from the rows of tents pitched on the rifle range where others were billeted, stood the handsome fort built by the Spanish. Its graceful arches had long since been landscaped, so Shofner darted up the road lined by acacia trees to a pathway bordered by brilliant red hibiscus and gardenias.2 He found some of the senior officers of the Fourth Marine Regiment sitting together.a They had received word from Admiral Hart's headquarters sixty miles away in Manila that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor. Their calmness surprised him.

Shofner should not have been taken aback. Every man in the room had been expecting war with the Empire of Japan. They had thought the war would start somewhere else, most likely in China. Up until a week ago, their regiment had been based in Shanghai. They had watched the emperor's troops steadily advance in China over the past few years as more and more divisions of the Imperial Japanese Army landed. The Japanese government had established a puppet government to rule a vast area in northern China it had renamed Manchukuo.

The Fourth Marines, well short of full strength at about eight hundred men, had been in no position to defend its quarter of Shanghai, much less protect U.S. interests in China. The situation had become so tense the marine officers concocted a plan in case of a sudden attack. They would fight their way toward an area of China not conquered by Japan. If the regiment was stopped, its men would be told essentially to "run for your life."3 The officers around the table this morning were thankful the U.S. government finally had yielded to the empire's dominance and pulled them out in late November 1941, at what now looked like the last possible moment.

Upon their arrival at Olongapo Naval Base on December 1, the Fourth Marines became part of Admiral Hart's Asiatic Fleet, whose cruisers and destroyers were anchored in Manila Harbor, on the other side of the peninsula from where they were sitting. Along with the fleet, U.S. forces included General Douglas MacArthur's 31,000 U.S. Army troops as well as the 120,000 officers and men of the Philippine National Army. Hart and MacArthur had been preparing for war with the Empire of Japan for years. The emperor must have been nuts to attack the U.S. Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor. Now that he had, his ships and planes were sure to be on their way here, to the island of Luzon, which held the capital of the Philippine government and the headquarters of the U.S. forces. The enemy's first strike against them, the officers agreed, would likely be by bombers flying off Formosa.b

With all this strategic talk, Shofner could see that no orders were in the offing, so he went back to his men. His headquarters company had assembled on the parade ground along with the men from the infantry companies. The word being passed around was succinct: "japs blew the hell out of Pearl Harbor." He confirmed the news not with fear, but with some relish. Lieutenant Austin "Shifty" Shofner of Shelbyville, Tennessee, had always loved a good fight. Of medium height but robust of build, he loved football, wrestling, and gambling of any kind. He did not think much of the Japanese. He told his men that an attack was expected any moment. Live ammunition would be issued immediately. Next came a sly grin. "Our play days are now over and we can start earning our money."4

The marines waited on the parade ground until the battalion commander arrived to address them. All liberties were canceled. The regimental band was being dissolved, as was the small detachment of marines that manned the naval station when the Fourth Marines arrived. These men would be formed into rifle platoons, which would then be divided among the rifle companies.5 Every man was needed because they had to defend not only Olongapo Naval Station, but another, smaller one at Mariveles, on the tip of the Bataan Peninsula. The 1st Battalion drew the job of protecting Mariveles. It would depart immediately.

The departure decreased the regiment by not quite half, leaving it the 2nd Battalion, Shofner's headquarters and service company, and a unit of navy medical personnel. The riflemen got to work creating defensive positions. They dug foxholes, emplaced their cannons, and strung barbed wire to stop a beach assault. They located caches of ammunition in handy places and surrounded them with sandbags. Defending Olongapo also meant protecting the navy's squadron of long- range scout planes, the PBYs. When not on patrol these flying boats swung at their anchors just off the dock. The marines positioned their machine guns to fire at attacking planes. Roadblocks were established around the base, although this was not much of a job since the only civilization nearby was the small town of Olongapo.

The men put their backs into the work. Every marine had seen the Japanese soldiers in action on the other side of street barricades in Shanghai. They had witnessed how brutal and violent they were to unarmed civilians. Most of them had heard what the Japanese had done to the people of Nanking. So they knew what to expect from a Japanese invasion. Shofner felt a twinge of embarrassment that these preparations had waited until now. The biggest exercise undertaken since their arrival had been a hike to a swimming beach. Shofner thought back to the day before, December 7, when he had spent the entire day looking for a spot to show movies. He let those thoughts go. His assignment was to create a bivouac for the battalion away from the naval station. The enemy's bombers were sure to aim for the warehouses and the fort. As noon on the eighth approached, he moved with the alacrity for which he was known. He took his company across the golf course, forded a creek, and began setting up camp in a mangrove swamp.

ON THE OTHER SIDE OF THE INTERNATIONAL DATE LINE, THE AFTERNOON OF December 7 found Ensign Vernon "Mike" Micheel of the United States Navy preparing to do battle with the Imperial Japanese Navy. He carried a sheaf of papers in his hands as he walked around the navy's air station in San Diego, known as North Island. Despite the frenzy around him, Mike moved with deliberate haste. He stopped at the different departments on the base: the Time Keeper, the Storeroom Keeper, the Chief Flight Instructor, and so forth, endeavoring to get his paperwork in order. A few hours before he and the other pilots of his training group, officially known as the Advanced Carrier Training Unit (ACTU), had been told that the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Their pilot training was being cut short. They would board USS Saratoga immediately and go to war.

The Sara, as her crew called her, could be seen from almost anywhere Mike walked. She was the navy's largest aircraft carrier and towered over North Island, the collection of landing strips and aircraft hangars on the isthmus that formed San Diego Harbor. She was the center of attention, surrounded by cranes and gangways. Several squadrons, which included maintenance personnel as well as the pilots, gunners, and airplanes, were being loaded aboard. Most of these crews had been scheduled to board the Sara today. The big fleet carrier had been refitted in a shipyard up the coast and, strangely, arrived a few minutes before the declaration of war.6 But new guys like Mike had had no such expectation.

Micheel prepared himself for active duty without the burning desire for revenge on the sneaky enemy to which most everyone around him pledged themselves. He knew he wasn't ready. He had not landed a plane on a carrier. Most of his flight time had been logged in biplanes. He had flown some hours in single-wing metal planes, but he had only just begun to fly the navy's new combat aircraft. Even when the Sara's torpedo defense alarm sounded and an attack appeared imminent, it was not in Mike's nature to let anger or ego overwhelm his assessment.7

Mike did not consider himself a natural pilot. He had not grown up making paper planes and following the exploits of pioneers like Charles Lindbergh. In 1940, the twenty-four-year-old dairy farmer went down to the draft board and discovered that he would be drafted in early 1941. If he enlisted, he could choose his service. His experiences in the ROTC, which had helped pay for college, had instilled in him a strong desire to avoid sleeping in a pup tent and eating cold rations. On a tip from a friend, he sought out a navy recruiter. The recruiter assured him that life in the navy was a whole lot better than in the infantry, but then he noticed Mike's college degree. "You know, we've got another place that you would fit, and that would be in the navy air corps. . . . It's the same thing as being on the ship with the regular navy people, but you get paid more."

"Well, that sounds good," Mike replied without enthusiasm. He had ridden on a plane once. "It was all right. But I wasn't thrilled about it." The recruiter, like all good recruiters, promised, "Well, you can get a chance to try it. If you don't like it, you can always switch back to the regular navy."

More than a year later, Mike arrived at North Island with a mission that placed him at the forefront of modern naval warfare. When civilians noticed the gold wings on his dress uniform, they usually assumed that he was a fighter pilot. The nation's memories of World War I were laced with the stories of fighter pilots dueling with the enemy across the heavens at hundreds of miles an hour. That heady mix of glamour and prestige also had fired the imaginations of the men with whom Mike had gone through flight training. Each cadet strove to be the best because only the best pilots became fighter pilots. When they graduated from the Naval Flight School at Pensacola, the new ensigns listed their preferred duty.

Though he had graduated in the top quarter of his class, and been offered the chance to become an instructor, Ensign Micheel listed dive- bomber as his top choice. While few had heard of it before their training, the dive-bomber was also a carrier-based plane. It served on the front line of America's armed forces. Instead of knocking down the enemy's planes, its mission was to find the enemy's ships and sink them. Mike wanted to fly from a carrier. In his usual quiet way he figured out that the surest way for him to become a carrier pilot was to become a dive- bomber. Many of his fellow classmates had listed fighter pilot as their first choice. Most of them would later find themselves behind the yoke of a four-engine bomber. Although officially ordered to a scouting squadron, he essentially received his first choice. Scouts and bombers flew the same plane and shared the same mission. Mike came to North Island to improve his navigation enough to be a great scout, but also to learn the art of destroying ships, especially enemy carriers.

Now he filed his paperwork and walked to the Bachelor Officers' Quarters to pack his bags without once having attempted the difficult maneuver of dive-bombing. As the sun set, a blackout order added to the confusion and tension. Men who had been on liberty or on leave continued to arrive, full of questions. Micheel and the other new pilots headed for the Sara and the moment they had been working toward. They boarded an aircraft carrier for the first time. Every space was being crammed with every pilot, mechanic, airplane, bullet, and bomb that could be had. Rumors ran wild. The new pilots found their way to officer country, the deck where officers' staterooms were located.

The loading went on through the night, without outside lights. Then dawn broke. The Sara stood out from North Island just before ten a.m. on December 8. The clang of the ship's general quarters alarm sounded minutes later. Before she departed, however, calmer heads had prevailed. Micheel and the other trainees had been ordered off. As the great ship headed for open sea, those watching her from the dock would have assumed the Sara and her escort of three destroyers were headed straight into combat.

Monday's newspapers carried the story of the "Jap attack on Pearl Harbor" as well as warnings from military and civilian leaders that an attack on the West Coast was likely. It fell to the servicemen of North Island to defend San Diego. The detachment of marines on the base began digging foxholes, setting up their guns, and protecting key buildings with stacks of sandbags. The airmen hardly knew how to prepare. The Sara had taken all of the combat planes assigned to Mike's training unit. All they had to fly were the ancient "Brewster Buffalo" and the SNJ, nicknamed the "Yellow Peril" because of its bright color and the inexperienced students who flew it.

FIRST THING MONDAY MORNING, DECEMBER 8, SIDNEY PHILLIPS RODE HIS BIKE down to Bienville Square in the center of town and met his pal William Oliver Brown, as agreed. They walked over to the Federal Building, which housed the recruiting offices of all the service branches. The line of men waiting to enlist in the navy stretched from the navy recruiting office, through the lobby, out the door, down the steps, down St. Georgia Street to the corner, and down St. Louis Street for half a block.8 Mobile, Alabama, was a navy town. The angry men in the line would have spat out the word "japs" frequently. Not the types to simply take their places behind this crowd, Sid and William, whom everybody called "W.O.," walked up to the head of the line to see what was going on. A Marine Corps recruiter spied the two teenagers, walked over, and asked, "You boys want to kill Japs?"

"Yeah," Sidney said, "that's the idea."

"Well, all you'll do in the navy is swab decks." The recruiter explained that if they wanted to kill "japs" they had to join the marines. "I guarantee you the Marine Corps will put you eyeball to eyeball with them." Neither Sid nor W.O. had ever heard about the marines beyond the name. They were not alone, which explained why the recruiter worked the crowd. The recruiter told them that the marines were part of the navy, in fact "the best part." Then he tried a different tack: mischief. "You can't get in the navy anyway. Your parents are married." Sid laughed out loud. He looked at W.O. and could see he was thinking the same thing. The marines might be their kind of outfit. But neither could sign up on the spot; as seventeen- year-olds, they had to bring the papers home and get their parents' signatures. A cursory fitness test also revealed that Sidney's color perception was impaired. Not to worry, the recruiter said, the color test will likely be changed soon. He told Sid to come back after Christmas. W.O. said he was willing to wait.

Sid went home and found that getting his parents' permission was a bit tougher than he had anticipated. His mother had two brothers in the navy--Joe Tucker was a pilot stationed in Pearl Harbor--and she felt that was enough. His father, the principal of Murphy High School, expected his son to be drafted soon, however. Young men were already being drafted and on this day President Roosevelt had declared war on Japan officially. But there was something else. The threat was real. Sid's father had served in World War I. He had raised his two children to love their country enough to protect it. When his only son stepped forward, he could not say no.

While his parents' discussion had only just begun, Sid figured his father would bring his mom around in time for him to go with W.O. However, it did not look like Sid's other best friend would be joining them. Eugene Sledge wanted to sign up, too, but his parents forbade him. Eugene had to finish high school. Eugene had a heart murmur. His brother had joined the army. Eugene's dad had lots of reasons. None satisfied his youngest son. Like Sid, Eugene felt a duty to serve. It came in part because of the sneak attack. His sense of duty also came from his family's long tradition of serving in the military. His dad, a doctor, had served in World War I. Both of his grandfathers had fought in the Civil War.

While Eugene and Sidney shared many interests, their passion for Civil War history bonded them. Most weekends found them at one of the battlefields just outside Mobile. Eugene's parents had a car for him, an almost unheard-of luxury, so they could drive over to Fort Blakeley or Spanish Fort. In part, the trips represented an escape from the structured lives they led. The ruins of the forts lay abandoned and ignored, so Sid and his buddy "Ugin" could do as they pleased. They loved to dig in the earthen breastworks for artifacts like minie balls and Confederate belt buckles. Eugene often brought his guns with them and they held target practice. They also read widely about the war and the battle fought there. The Army of the Confederacy had held Fort Blakeley even after the Yankees closed the port of Mobile and conquered Spanish Fort. On the same day General Lee signed the surrender at Appomattox, some twenty thousand men fought the last major battle of the Civil War at Blakeley. The Eighty-second Ohio led the Yankees' charge, which at last flushed the outnumbered and outgunned Confederates from their positions. Sid and Eugene loved tracing each unit's actions, refighting the battle from the mortar pits, rifle pits, and the great redoubts of the artillery.

The war against Japan undoubtedly would become as important as the Civil War. " The dirty japs," as most Americans referred to them, had launched a sneak attack while their ambassadors in D.C. spoke of peace. It was treachery. The desire to be a part of their country's glorious victory burned inside of Sid and Eugene. Like the Rebels at Fort Blakeley, who fought to the death long after the war was lost, they longed to prove their courage for all time. Now, if only they could get their parents' permission.

WHILE EVERYONE SPOKE ENDLESSLY ABOUT PEARL HARBOR, CORPORAL JOHN Basilone was incensed by the Japanese attack on the Philippines. His reaction surprised no one in his company. Although a corporal in the marines, Basilone had served a two-year hitch with the army, most of it in Manila, years ago. He had told so many stories about Manila that his friends had long ago nicknamed him "Manila John."9 Every marine told sea stories. Stationed in a tent camp on the coast of North Carolina, they had little recreation aside from shooting the breeze. The tattoo on John's right biceps of a beautiful woman elicited comments and questions. He told them that her name was Lolita and he had met her in Manila "quite by chance, during one of those storms which blew up so suddenly."10 To escape the driving rain he stepped into a small club and there she was.

John had known neither the Filipinos nor their country until Lolita had introduced him. Though poor, the Filipinos--who pronounced the word Pill-ee-peenos--worked hard and took pride in their identity. They had fought a protracted war for their independence and forced the U.S. government to establish a timetable for its withdrawal. With the issue of independence settled before his arrival, John had come to know a woman and a people who loved America. They looked to America for help. The first president of the Philippines had asked General Douglas MacArthur to build the country's army and command it as field marshal. To protect the fledgling democracy until it could defend itself, the U.S. Army maintained a large force there. Even as a lowly private, Basilone understood the biggest threat came from Japan.11 They had been trying to push America out of the Far East for years.

December 9 brought news of Japanese attacks on other countries and islands in the Pacific. As the scale of their conquest in the Pacific shocked the nation, John told everyone that Manila would not fall.12 General MacArthur commanded a powerful force from his suite atop the Manila Hotel, where he could look out at the bay on one side and over the city's main thoroughfare, Dewey Boulevard, on the other. Northern Luzon had impressive defenses, the most important of which John had seen one evening on a boat trip with Lolita.13 She directed their boat out of Manila Bay and around the tip of the Bataan Peninsula into Subic Bay. They motored up along the northern coast of Bataan, in the direction of Olongapo, for dinner at a special restaurant. It had been a memorable night in a lot of ways, but John also recalled passing the island fortress guarding the entrance to Manila Bay: Corregidor, known as "the Rock." Its ancient rock walls, topped by giant coastal artillery, towered above the greatest warships ever built.

By the time his hitch with the army expired, John had decided to go home a single man. Lolita came looking for him right before he shipped out. He had been lucky to miss her, he liked to joke. She brought a machete and cut his seabag in half.14 Being marines, his friends believed about half of what he told them.15 But the point of John's stories was never to make himself look good. He liked to laugh and swap stories. A careful listener would have, however, deduced something else. John loved Manila because it had been there that he had come into his own. The adventurous and physically demanding life of a professional soldier had quelled a deep-seated restlessness. Unlike his struggles in civilian life, John had discovered a knack for soldiering.

Manila John's path from the army to the Marine Corps had been neither straight nor easy, but he eventually had made it from Manila to the machine- gun section of Dog Company, 1st Battalion, Seventh Marine Regiment (D/1/7). He faced the war secure in his place in the world. He loved being a marine. He knew his job. Instead of being a cause of concern for his parents, he was sending home $40 a month to his mother.16 That peace brought out his natural disposition: a cheerful, fun- loving, easygoing spirit that drew others to him.17 He had his feelings inscribed on his left shoulder. It bore a sword slashing down through a banner proclaiming "Death Before Dishonor."

LIEUTENANT SHOFNER'S WAR GREW SLOWLY. THE ENEMY BOMBED THE U.S. bases around Luzon for a few days before they began landing troops on December 10. They chose isolated areas and their troops walked ashore. Reports of their movements reached the Fourth Marines almost hourly as the top brass in Manila struggled to devise plans and their various units strove to carry them out. The Fourth continued to man its post at Olongapo despite rumors of other assignments. During the day, the marines prepared to defend the beaches. The air raid alarm sounded often but, so far, nothing. At night, the marines marched back to their camp in the swamp. The blackout was enforced. Food had to be rationed. They ate twice a day or, as the saying went, "breakfast before daylight and dinner after dark."18 Inside of two weeks, someone surely noted, they had gone from Peking duck to cold C rations. A few days of foul weather made camp miserable, but the storm did bring a respite from reports of fresh attacks.

The twelfth dawned clear, so the marines watched as a few of the PBYs of Navy Patrol Wing Ten landed in the bay. The morning's patrol was over and the seamen had secured their planes when five enemy fighter planes fell upon them. With their heavy machine guns and 20mm cannons, the Japanese planes quickly destroyed seven flying boats, the entire squadron. Two or three attackers made a run at the marines' base, guns blazing. About forty .30-caliber machine guns returned their fire. No one hit a plane. The .30 caliber had not been designed as an antiaircraft gun, but the marines pulled their triggers anyway. One gunner swung hard to track his target and shot holes in the water tower.

The next day the alarm sounded at ten thirty a.m. for what Shofner thought must be the fiftieth time. As the commanding officer (the CO) of the Headquarters Company, he led it once again across the golf course and into the swamp. He looked up, counted twenty-seven Japanese bombers above him, and heard a noise he had never heard before. The sound of bombs falling toward him was unforgettable. Explosions erupted as the planes disappeared. Shofner returned to the base. A sudden gust of wind, he learned, had driven the bombs past the base and into the town. The village was on fire and the marines went to assist. They found a dozen had been killed and many more wounded. Bombs landed near the regiment's field hospital, although its tents, emblazoned with large red crosses on fields of white, had been set up a mile out of town. The marines decided the emperor's air force had aimed for the hospital and it made them angry.

The attack prompted Shofner's CO to reassess the situation. The regimental commander could not allow his men to be killed before the land campaign began. If the assault came at Olongapo, the defenses were as ready as they could be. But his unit was not going to sit on a target. The Fourth Marines moved their camp a few miles into the hills, where the jungle hid them from bombers. A skeleton crew manned the naval base during the day, but the rest prepared for a battle they knew was coming somewhere, soon. The enemy was on the move. As the battalion's supply officer, Shofner concentrated on moving necessary supplies to the new bivouac. As an officer he did not lift boxes, of course, but he had to decide what could fit on their limited supply of trucks. Marines from the rifle companies, meantime, rounded up all Japanese civilians in Olongapo and turned them over to the army's police force.19

When the communication lines to Manila went dead, it was assumed this was the work of saboteurs. News of other enemy landings on Luzon continued to get through to them by runner and radio. The enemy's bombers paid another visit to Olongapo before the night of December 22, when the regiment went on high alert at about one thirty a.m. The first report stated that fifteen transports had landed enemy troops on Lingayen Gulf. Top U.S. commanders always had expected the main assault to cross the beaches of Lingayen. The Fourth Marines were ordered to prepare to move out to repulse it. The next communication reported "87 jap transports." A long, anxious night passed. The regiment stayed put. Shofner assumed it was because they were only five hundred men. Later he found out the regiment had been put under MacArthur's command. While the Fourth awaited its orders, the enemy's troop transports were spotted in Subic Bay. The marines charged down to defend Olongapo but found an empty ocean.

The Fourth's CO drove to Manila to assess the situation. At six p.m. on December 24, Shofner watched the colonel's car return to their camp at high speed. A battalion officers' conference followed. Colonel Howard told them he had been ordered to withdraw immediately to the small base at Mariveles, on the tip of the Bataan Peninsula. Units of the Imperial Japanese Army had overwhelmed all opposition easily and had advanced to within forty miles of their position. To his officers, he likely also admitted the full scope of the situation. From his conversations with Admiral Hart and later with General MacArthur and his staff, it was clear that the U.S. forces were in disarray. MacArthur's chief of staff, General Richard Sutherland, had told Howard the Japanese "were converging on Manila from three directions."20 The enemy air force had destroyed most of the thirty-seven new B-17 bombers and the remainder had flown south to Mindanao. Admiral Hart was departing by submarine and taking his remaining fleet south. General MacArthur was abandoning Manila and ordering all of his troops to prepare for a defensive stand on the Bataan Peninsula. MacArthur's headquarters was moving to the island of Corregidor. He ordered the Fourth Marines, after picking up its 1st Battalion in Mariveles, to Corregidor to protect his headquarters. Colonel Howard told his officers to begin packing immediately.

Lieutenant Shofner's job as the battalion's logistics officer demanded his best efforts to get all of the equipment and supplies on the trucks and headed south on the dirt road. The first convoy of trucks left about noon on Christmas Day. Shofner and his friend Lieutenant Nutter led some men back to the naval station. They had a few hours to get the necessities. So far as their personal gear, each marine had a backpack. Beyond that, the colonel had allowed one footlocker for officers. Everything else had to be left behind.

Shofner hated to leave behind the large and diverse collection of personal effects he had stored in the warehouse at the dock. It caught him off guard. As the scion of a well-to-do family, he had become an officer and a gentleman after serving as president of his fraternity (Kappa Alpha), lettering on the varsity football team of the University of Tennessee, and earning a scholarship from the "T" Club as "the athlete with the highest grades." His mountain of baggage included not only an array of military uniforms and sporting equipment of all types, but also a few dozen suits for every occasion--from black tie, to silk, to sharkskin. In Shanghai he had amassed an impressive array of exquisite Chinese furniture, furnishings, art, and apparel. Some of the silken damasks and jade carvings doubtless were intended as gifts for his girlfriend, his mother, or others in his large family. When he had been posted to Shanghai six months earlier and learned war was imminent, he had been pleased. Shofners had fought in every American war. The idea of retreating, however, had never occurred to him.

He packed his footlocker with necessities, including just one small memorial: a plaque bearing the insignia of the Marine Corps from the Fourth Marine Regiment's Club. As he sped away, he hoped his oriental rugs and ivory statuettes would be found by some local Filipino.

Shofner arrived at Camp Carefree, an army rest camp at the tip of Bataan, that evening and enjoyed a turkey sandwich for his Christmas Day dinner. So far as he could tell, Bataan had not been prepared for a defensive stand. He found an open bunk in the officers' quarters and let exhaustion overtake him. The air raid siren woke him at midnight. Everyone ran outside and lay down in an open field, as ordered. From where he lay, Shofner could see a freighter burning just offshore, and beyond it, the city of Manila lit by a hundred raging fires. MacArthur had ordered the city, known as the Pearl of the Orient, abandoned by his forces. He informed the Imperial Japanese Army it was open to them. They bombed it anyway.

The enemy had gotten the drop on the United States. That much was obvious on Christmas Day. The officers and men of the Fourth Marines committed themselves to hanging on until the United States Navy showed up with reinforcements. Then the bastards would catch hell.

THE DAY AFTER CHRISTMAS, SID, W.O., AND SOME OTHERS WERE SWORN IN. JUST like that they were marines. People had heard about the marines now. The marines who defended Wake Island had repulsed the first attempt by Japan to invade the island a few days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. When asked later to detail his supply needs, the officer in charge had radioed "send us more japs!"c Wake had been overrun on Christmas Eve, but not without the kind of fight Americans had seen lacking elsewhere. Preparing to depart, Sid got together with Eugene. Eugene gave Sid a copy of Barrack-Room Ballads, by Rudyard Kipling, as a going-away present. The book contained a favorite poem, "Gunga Din." Both of them could quote passages from memory, such as the opening stanza:

You may talk o' gin and beer

When you're quartered safe out 'ere . . .

But if it comes to slaughter

You will do your work on water,

An' you'll lick the bloomin' boots of 'im that's got it.

Now in Injia's sunny clime,

Where I used to spend my time

A-servin' of 'Er Majesty the Queen,

Of all them black-faced crew

The finest man I knew

Was our regimental bhisti, Gunga Din.

It was "Din! Din! Din!

You limpin' lump o' brick-dust, Gunga Din! . . ."

Sid did not open the book on the steam train to Parris Island, South Carolina. The new life intoxicated him. He and W.O. and a carload of new best friends sang songs. Upon arrival, Sid learned he was not a marine. He was a shitbird. In the estimation of his drill instructor (DI), who delivered his opinion at high volume and at close range, Sid Phillips was not going to ever reach the exalted position of marine. He was his mother's mistake. Then it was time to run: run to get their gear, run to their barracks, run to the parade ground, run, run, run! To Sid's complete surprise, his training focused on earning the privilege of being a United States Marine. Only occasionally did he dig a foxhole, stab a dummy with a bayonet, or learn something related to killing Japanese soldiers. The Marine Corps set a high standard with the rigors of boot camp. The humiliation and the profanity heaped upon all the boots (recruits), as well as the all-encompassing demands placed upon them, went well beyond the other services. Every action would be performed the Marine Corps way using Marine Corps terminology, or else.

Sidney and W.O. and their new friend John Tatum, also from Alabama, had been raised to respect and obey authority. They adjusted to boot camp rather easily. Shorn not just of hair but also of all personal privacy, Sid disliked using the head (toilet) in front of sixty others and lining up to have his penis inspected for gonorrhea. The prospect held out by his instructors, that of becoming the world's best fighting man, seemed worth the punishment. On the first day, each boot had been issued a rifle, a 1903 bolt-action Springfield, so Sid looked forward to the day when he would be taught to use it. Rifle instruction came last. In the meantime he and his fellow boots drilled ceaselessly, learning to march in lockstep. To survive, they learned their instructor's personal marching cadence. No drill instructors yelled, "March, one, two, three." It demanded too much from the vocal cords. Besides, a DI could really vent his disgust of the shitbirds by shouting something like "HAWrsh! AWN! UP! REEP!"21

CORREGIDOR INSPIRED CONFIDENCE IN THE MEN OF THE FOURTH MARINES. After arriving by ferry on North Dock, they put their gear on a trolley and began the climb up the steep hill. They had all heard the Rock was an impregnable fortress. Their escort described the great tunnels carved in the rock below them and the huge coastal gun emplacements on the hills above them. The island was shaped like a tadpole; its tail stuck into Manila Harbor, its round head facing the South China Sea. The narrow tail was mostly rocks and beaches. Dominated by Malinta Hill, the tadpole's tail held the docks, power station, and warehouses; this area was called Bottomside. Beyond Malinta Hill, they came to the high hill known as Middleside, where their barracks were located, as well as a hospital and a recreational club. Beyond Middleside was another, steeper hill, called Topside, encompassing most of the wide area of the tadpole's head. On Topside, the lush forest gave way to manicured lawns surrounding stately mansions for officers, a golf course, and a profusion of casemates holding the giant coastal artillery. More than fifty big guns, from three inches to twelve inches in diameter, had been emplaced. The Rock, kept cooler than the mainland by an ocean breeze, had it all.

Having arrived at Middleside Barracks on the evening of December 27, the marines spent two quiet days getting squared away. Organizing the supplies kept Shofner busy. His regiment, which now included its 1st Battalion as well as a detachment of four hundred marines from another base, brought rations to feed its twelve hundred men for at least six months, ammunition for ten days of heavy combat, khaki uniforms to last for two years, and medicine and equipment for a one-hundred-bed hospital. Of course Corregidor had mountains of munitions already stockpiled.

When the air raid sirens went off about noon on December 29, no one paid much attention. The Japanese had never bombed Corregidor. Shofner was standing near the barracks when he saw the formation of planes. The antiaircraft guns began firing. The sun glinted off the metal shapes falling toward him. He ran into the bombproof barracks. He joined the rest of the regiment, every last man of whom was splayed out on his belly. One bomb came through the roof but exploded on an upper floor; another could be heard crashing through but did not detonate; many others went off nearby. "And thus began," Shofner wrote in his diary, "the worst day I have ever spent."

A bomb had wounded one marine. He was taken to the hospital as everyone else abandoned Middleside Barracks. It had become a giant target and more airplanes were overhead. Shofner met some nurses looking for a doctor; bombs had hit the rear of their barracks. All Shofner could find was a dentist, but he sent him. Another squadron of bombers came over, then another and another. He lost count after a dozen formations had each released a vast amount of high explosives. Most of the time he lay on his back, watching the Rock's antiaircraft (ack-ack) shells explode well short of their targets. He wondered whether the planes were too high, if the aim was off or the proper fuses were missing, or if perhaps the poor shooting was the fault of untrained personnel. He could not tell. The bombs fell without a discernible pattern so one could only hope, intensely. The last echo faded four hours later. The marines sustained four casualties, one of whom later died. The buildings of Middleside, including his barracks, lost the capacity to provide much shelter, much less a sense of security.

Irritated by doubt for the first time, Shofner got to work. His company was ordered to set up camp in James Ravine. That meant setting up a galley to feed the men, laying communications wire, and other preparations. He worked all night. The other units of the regiment moved to their sectors and prepared to defend the beaches of Corregidor. The 1st Battalion took the most vulnerable sector, encompassing Malinta Hill and Bottomside. Shofner's battalion had the easier job of securing Middleside, where he was, and Topside. Since it was unlikely the enemy would try to land anywhere but Bottomside, Shofner's position was considered a reserve one. Still, all hands fell to, spending the balance of each day stringing barbed wire, placing land mines, and digging trenches, antitank traps, and caves for shelter. The air alarm occasionally failed to go off and bombs detonated close to him a few times. As battalion mess officer, he saw to it that each man received two rations per day. Thankfully there was plenty of drinking water and they could bathe in the sea. Learning to keep oneself near shelter and to run for it at the first hint of an aircraft engine took time. In the course of the next ten days, 36 marines were killed and another 140 were wounded. 22

THE MONTH OF DECEMBER HAD PASSED AT NORTH ISLAND WITH ALMOST NO flight training. Mike had flown once. The regime of daily instruction had resumed in January. The pilots in the Advanced Carrier Training Unit had promptly made a mess of it. Every day for a week, one of Mike's colleagues had landed without first lowering the plane's wheels, or tipped the plane over on the ground. The mistakes could have resulted from the pause in training, or perhaps the ensigns had war jitters. When it happened again on January 12, their CO lined up the ensigns in the hangar at four thirty p.m."I don't want any more accidents," Commander Moebus bellowed."The first guy that has an accident, he'll find out what I mean by having no more accidents!"

After the meeting, Micheel took off in a bright yellow SNJ to practice flying at night by flying at dusk. He flew for over an hour and approached the landing field before full dark. Just as his wheels began to touch pavement, the control tower radioed to him, "Abort your landing! Take off ! Plane on the runway!" Mike pulled the plane up. As he flew along the expanse of runway, he looked down and saw only one other plane, well out of his way. Ticked off, he decided he would not make a complete new approach through the traffic pattern. He kept the aircraft prepared for landing: prop in a low pitch, a rich mixture in the manifold, flaps down. He came around quickly and began to land again, nose into the wind. The tower came on the radio again and said he was cleared. Just before touchdown, the Klaxon on the control tower began to screech, indicating his wheels were up. Mike had brought them up after the first attempt. He shoved the throttle forward but it was too late. The Yellow Peril slid on its underbelly. Screeching down the center of the main runway left him flushed with embarrassment.

The plane's wooden propeller was a goner and the engine needed some maintenance due to the abrupt stop. The mechanics would have to change the flaps and bend the metal fuselage in places. The SNJ was not irreparably damaged, but now he had to go face Commander Moebus. Ensign Micheel reported to his CO and admitted he had been distracted and had not run through his landing checklist a second time. Just as Mike feared, the commander was hot. He charged Mike with "direct disobedience of orders" and grounded him immediately. Moebus decided to make an example of Mike to all of his students. He wrote the navy's Bureau of Navigation, the governing body of naval aviation. After explaining the chronic problems he was having with his students as well as the warning he had given Micheel just before he took off, Moebus requested that Ensign Vernon Micheel be "ordered to duty not involving flying." Only such drastic action would get his students' attention.

Moebus's letter betrayed more than just the exasperation of a commander, though. He attributed the problems in his ACTU to "inaptitude incidental to entry of large numbers of cadets and the forced draft method of training in large training centers which does not entirely eliminate mediocre material." Put another way, the navy's new flight training program was failing. Commander L. A. Moebus expressed the frustration many graduates of the Naval Academy at Annapolis felt toward the hordes of civilians now coming through the Naval Aviation program. Men like Vernon Micheel, who had attended college to become a dairy farmer, could never be a professional on par with an Annapolis man.

While waiting for a reply from the bureau, Moebus ordered his wayward ensign to stay with the wounded SNJ. Beginning the next day, as the mechanics repaired it, Ensign Micheel prepared a report listing the cost of each new part and of each hour of labor expended. The roar of aircraft engines echoed through the big hangar constantly. Mike tried not to think about where he would wind up if he was expelled from the ACTU.

THE JAPANESE STOPPED BOMBING THE ROCK IN MID-JANUARY, MUCH TO LIEUTENANT Shofner's relief. The pause gave the Americans time to prepare. General MacArthur issued a statement to all his unit commanders. He ordered each company commander to deliver this message to his men: "Help is on the way from the United States. Thousands of troops and hundreds of planes are being dispatched. The exact time of arrival of reinforcements is unknown . . . it is imperative that our troops hold out until these reinforcements arrive. No further retreat is possible. We have more troops in Bataan than the Japanese have thrown against us; our supplies are ample; a determined defense will defeat the enemys' attack. It is a question now of courage and determination. If we fight, we will win; if we retreat, we will be destroyed."23 The message improved morale on the island, even as the sounds of the battle on Bataan reached them.

In early February, the enemy began shelling Corregidor with their artillery. It became clear to all immediately that shells fired from big guns hurt a lot more than bombs dropped from twenty thousand feet. The whistle of incoming rounds lasted only a few seconds, as opposed to the long, monotonous hum of an approaching bomber squadron. The whistle came on rainy days and at night. It made walking aboveground hazardous. The marines, who lived on top of the island, began to envy the army, most of whom had crowded into Malinta Tunnel, deep under the Rock.

Shofner was promoted to captain on January 5 and took command of the 2nd Battalion's reserve company. His two rifle platoons and one machine-gun platoon stood ready to answer a call from any unit on the beaches. The shelling usually cut the communications wires, however, so there were more and more periods of time when he only knew what he could see. He had his men shovel several feet of dirt into the walls of Middleside Barracks to create a final defensive line. He had them dig caves to give them shelter from the barrages.

Shofner, nicknamed "Shifty" by his friends because he always had an eye for tricks and shortcuts, would have certainly begun to notice the problems with the island's renowned defenses. Some of the great ten-inch guns could not be turned to engage the enemy's artillery because they had been built to face ships at sea. A few of the other main gun batteries already had been destroyed because their concrete barbettes left them open to the sky. The island's power plant had been built in an exposed position. The Fourth Marines learned quickly how to keep low. They suffered fewer casualties in February than they had in January, although they received more gunfire. At night they stood their posts, watching for landing boats and hoping for their navy. If an electrical storm brought flashes of light, one of Shofner's guards was sure to report, "that's our fleet coming in."

The departure of the president of the Philippines, Manuel Quezon, could not be hidden from the men. The gold and silver of his treasury had departed already. These troubling signs put the same questions to everyone's lips: "Where the hell's the navy?" and "What's the matter back home?"24

ENSIGN MICHEEL TRACKED THE COST OF REPAIRING THE AIRPLANE WITHOUT complaint. While his colleagues roared aloft, he spent his days watching the mechanics work. He enjoyed learning the intricacies of engines and ailerons. Three weeks passed before the CO called him into the office to inform him he had been reinstated. Commander Moebus did not elaborate, but Mike could guess the truth. The chief of the Bureau of Naval Aviation had reviewed his file, concluded that the wheels-up landing had been an isolated lapse, and sent a reply to Moebus that fell just short of saying, "Hey, there's a war on, you know."

Mike had missed out on advanced instruction in tactical flying, navigation, and scouting. He took his first flight in the backseat of an SNJ, watching one of his peers work through a navigation problem. A schedule of classroom instruction mixed with flight time followed. Ten days later, on February 19, the ACTU received the navy's modern combat aircraft. For some of his classmates, this meant climbing into an F4F Wildcat, the navy's best fighter. For Mike, it meant climbing into the SBD Dauntless, the navy's scouting and dive bombing aircraft. His squadron had received SBD-3s, the latest version. He began flying an hour or so most every day. Sometimes an instructor flew in the plane, with Micheel riding in the rear seat gunner's position, but usually Mike flew himself as part of a group led by an instructor. Although his daily instruction varied somewhat, two advanced maneuvers came to the fore.

Micheel made his first attempts at dive-bombing. Putting a plane into a seventy-degree dive from twelve thousand feet and dropping like a stone took a young man's courage. By deploying special flaps on the SBD's wings, called dive brakes, the pilot could hold the plane under 245 knots. But the steep angle lifted him off his seat and had him hanging in his harness, with one hand on the control stick and one eye stuck on the telescope set into the windshield of the Dauntless. Through the bombsight, he watched the target grow in size rapidly. At about two thousand feet above the target, he toggled the bomb release and pulled out of the dive. The force of gravity squished him into the bottom of his seat.

Part of every day had to be spent on the other great challenge of naval aviation, landing his Dauntless on the deck of an aircraft carrier. The difficulty of a carrier landing had loomed on the horizon since flight school. Pilots practiced it, logically enough, by landing on a strip of the runway that bore the outline of a carrier deck.

It began with a specific approach pattern. The pilot approached the ship from behind. He flew past the carrier on its starboard (right-hand) side at about one thousand feet. The pilot was now "in the groove." Once he passed the carrier by a half mile (depending on how many planes were also in the groove), he would make a left-hand turn and come back toward it. Lowering his elevation, his landing flaps, his wheels, and most important, his "tail hook," the pilot made his final preparations for landing. Looking to his left as he approached the ship's bow, he had an unobstructed view of any other planes landing on the deck ahead of him. Spotters on the carrier deck would signal him if they saw a problem with his plane or on the deck.

As the pilot reached the stern of the ship, he began a hard left-hand turn that would bring him around 180 degrees and just over the stern of the ship. At this point the pilot could look down and see a man standing on the stern port corner of the carrier with large paddles in his hands. Usually dressed in a suit of yellow to make him clearly visible, the Landing Signal Officer (LSO) gave the pilot directions by waving his big paddles and tilting his body. If the pilot followed those commands exactly, the LSO slashed one paddle across his neck. The pilot cut the engine and his plane dropped onto the deck, its tail hook caught a wire, and he was home free. It was a controlled crash landing onto a moving target.

Mike and his classmates spent many hours mastering the fundamentals of carrier landings on a remote section of runway. A pilot could not come in too fast, nor too slow, or too high or too low. His plane also had to be in the proper "attitude" in the air, with its nose up and hook down, in order to make a perfect three- point (one for each wheel) landing. In a few hours of flying time, the ensigns simulated as many landings as they could: circle the deck, get the slash (or "cut"), crash, power up and away. Then they met back in their classrooms with the LSO, who reviewed each of their techniques in detail.

None of their practice took place on a carrier. The navy, as the ensigns likely found out through scuttlebutt, was running short on those. Saratoga had been torpedoed in January and had sailed to Bremerton, Washington, for repairs. To keep the enemy guessing about whether the Sara had survived, her status had not been made public. Instead, the newspapers carried stories of Admiral Halsey using Enterprise to strike Japanese strongholds in the Marshall Islands, in the central Pacific. "Pearl Harbor Avenged" read one headline, but about then the British fortress on Singapore fell.25 The enemy now controlled half of the Pacific Ocean. In the bull sessions held at the officers' club, the ensigns would have discussed the futures of the three remaining fleet carriers in the Pacific--Yorktown, Lexington, and Enterprise--and Hornet, due to be commissioned in early April. Each pilot already had been assigned to serve on one of them. Ensign Micheel knew he would be joining USS Enterprise. As a dive-bomber pilot, Mike likely wondered just how many big carriers the enemy had, exactly, since he had to go sink them.

PRIVATES SIDNEY PHILLIPS, W. O. BROWN, AND JOHN TATUM, WHOM THEY HAD taken to calling "Deacon" because of his penchant for quoting scripture, departed Parris Island wearing the emblems of the United States Marine Corps: an eagle, globe, and fouled anchor. While few of their cohorts had failed to make the grade, each of them came away with a few firm beliefs. The USMC was the world's best combat unit. The marines were the first to fight. Their mission, amphibious assault, was the most difficult feat of arms. Once marines seized the beachhead, the army "doggies" would come in and hold it. These beliefs had been burned into them while they had learned to perform the manual of arms with precision, slapping their rifles so hard the sound carried a hundred yards. Being one small part of this great team gave Sidney a feeling of strength and comfort unlike anything he had ever experienced.

After arriving by train at New River, North Carolina, one afternoon in mid-February, they formed into ranks on a great muddy field. Ahead of them stood a large tent, its open flaps revealing bright lights and busy activity. One by one, each man was called forward. Inside, NCOs (noncommissioned officers, such as corporals and sergeants) met and interviewed him. Sid walked through the mud, answered the NCOs' questions, and was assigned to How Company, 2nd Battalion, First Marines (H/2/1). So was W.O. The Deacon received the same assignment. What luck, they thought. After a time Sidney realized everyone in their group had been assigned to the 2nd Battalion, First Marines.

The three friends stuck together and were assigned the same hut. The next morning they found three inches of snow on the ground and no orders to follow. For the next few days they just had to keep the stove in their hut hot. More men arrived, as did the USMC's newest uniform, the dungarees. The two-piece uniform of heavy woven fabric, intended for use in the field and in combat, was the first piece of equipment issued that had been designed for the new war instead of the last Great War. Sidney preferred it to his khaki uniform because it had large pockets and a stencil of the corps' emblem on the breast. The helmet he wore was the same kind his father had worn in France.

Instruction began on February 18, when the NCOs introduced them to some of the weapons used by their company: the .30-caliber Browning Machine Gun and the 81mm mortar. These and the other heavy weapons of How Company, they were told, would support the assault by the riflemen of the other companies of their battalion (Easy, Fox, and George). The 81mm mortar captured the attention of Sid and Deacon. Big guns had always fascinated them and they made sure their NCO knew it. W.O. was happy enough to stay with them. Other men disparaged the 81mm as "the stovepipe" and tried to get assigned something else. The self- selection worked. After a few weeks, the NCOs assigned the three friends to the same mortar squad, #4 gun, of the 81mm mortar platoon. All six members of #4 gun squad were Southerners except for Carl Ransom from Vermont. Ransom, hearing the others naming themselves the Rebel Squad, quickly asserted that he had grown up in the southern bedroom of a house on the south side of the street.

Although they occasionally had an afternoon of instruction on something else, the #4 squad quickly became focused on their weapon. Sid repeated sections of its manual over and over, chanting it like a rhyme. The 81mm mortar was "a smooth bore, muzzle loading, hand fed, high angle type of fire . . ." Corporal Benson, who commanded #4 gun, had them begin mastering the precise movements for assembling and firing the weapons by repetition. At Benson's command, one man set down the base plate, another the bipod, and a third the tube. The job of clamping the three parts together naturally fell to Deacon. A bit taller and a bit older, John Tatum took it all more seriously than Sidney and W.O. Corporal Benson took the mortar sights from the case and attached and adjusted them.

The endless repetition and chanting quickly led to competition between the gun squads. Deacon wanted to be the fastest. He studied The Marine's Handbook, the red book issued to all privates. By early March Deacon became acting corporal even before he had earned his stripe as a private first class. Sid and W.O. had no wish for promotion. They enjoyed the rivalry, though, and #4 squad assembled their mortar in the respectable time of fifty-five seconds. Corporal Benson never praised them.

Like most NCOs, Benson regarded them as too soft to be good marines. When the new men complained about the cold, they were told to wait until summer, when the chiggers and mosquitoes returned. Any new marines who rejoiced at receiving steel bunks on March 9 were told they were babies who had it too easy. Benson had lived in a tent on some island called Culebra for months, and that, he assured them, had been much worse. Sometimes, when his squad beat the squads of the mortar platoon, Benson might be inspired to tell them a few sea stories of a marine's life in Puerto Rico or Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. The First Marines had spent much of the past three years in the Caribbean, working out the techniques of amphibious landings. They had been in the boonies so long they had taken to calling themselves "the Raggedy-Assed Marines." Benson had learned to curse in Spanish, and when he started in, it brought a slow, mischievous smile to Sid's face. Deacon might be horrified, but Sidney Phillips loved a good laugh.

THE GREAT INFLUX OF NEW MARINES WAS LEADING TO PROMOTIONS FOR THE old hands. A few weeks earlier, Manila John had made sergeant.26 His company not only received new marines, but also a number of experienced men who had asked to be transferred. John's regiment, the Seventh, was considered good duty because by early March it was clear the Seventh would lead the attack against the enemy. It had the highest percentage of experienced marines and it was receiving all the new equipment first. As they prepared for the first amphibious assault--which, for all the talk, the USMC had never once performed against a hostile foe--the men in John's machinegun section were realizing they had an unusual sergeant. It wasn't his sea stories about life as a soldier, or even his insistence that he was going to "land on Dewey Boulevard and liberate Manila."27 All sergeants had sea stories and some of those wanted to liberate Shanghai. Sergeant Basilone, with his prizefighter's physique and dark complexion, made a big impression, but his relaxed manner said he was just one of the guys.

Most NCOs liked to make their men hop. Manila John regarded his men, new or old, as part of the fraternity.28 He did not struggle to enforce discipline. John set the standard.29 He loved being a marine and he expected the others to feel the same. He expected them to obey his orders because that's what marines did. He expected them to train hard during the week and then go into Wilmington or Jacksonville with their buddies and drink beer. That's what he did. Manila's best friend was another sergeant named J. P. Morgan. Morgan, known for being difficult, had a tattoo like John, only his was on the base of his thumb. When he had had it inked years previously, the tattoo had symbolized his Native American heritage. When anyone looked at it in 1941, though, they saw a swastika, the symbol of Hitler's Nazi Party.30 The identification did little to improve J.P.'s demeanor.

John and J.P. each commanded one section of .30-caliber machine guns in Dog Company. At the moment, Manila spent most days instructing the men of his company, and to a certain extent the men of his battalion, on the operation of the Browning .30-caliber water-cooled machine gun. The machine gun's reputation of immense power drew lots of enthusiastic young men. They did not get lectures from their sergeant; they got hands-on demonstrations. The grace and ease with which he handled the weapon belied the short, choppy sentences he used to describe it.31 Despite popular perceptions, the machine gun was not like a hose that sprayed out an endless stream. Holding the trigger down would burn out the barrel. Replacing a barrel took time. Spraying it all around might work for an enemy at close range, but it would prevent the gunner from dominating parts of the battlefield in the way it was designed to do.

Dominating the field meant preventing the enemy from ever getting close. Fire short bursts, John would have cautioned. That kept the gun cool. To make those bursts effective, don't free-hand the aim. Use the traverse and elevation mechanism (T&E). Slight turns of these dials made minute adjustments to the aim, which produced significant changes at two hundred yards. Good gunners did not aim for individuals. They created kill zones way out there on the battlefield. They killed the enemy in big groups or forced them to keep their heads down long enough to allow marines to attack them. A good gunner also knew his machine intimately. It began with being able to break the gun into its main components, or fieldstrip it, to clean them. Like any machine, however, the machine gun could be tuned. The rate of fire could be adjusted and, like all sergeants in all machine-gun sections, John had his guns set to his preferred cyclical rate, the one that he felt balanced the needs of endurance and killing power.

Manila John's battalion also spent a lot of March in remote areas of the base, living in their pup tents. The CO of 1/7, Major Lewis Puller, pushed them hard. Unlike some other officers, the major went with them on their six a.m. hikes, matching them step for step. He liked to have them work on their field problems near where the artillery units fired their 75mm and 105mm cannons.32

The word on Major Puller was that he had proven his mettle in the guerrilla wars in South America. Puller's nickname, "Chesty," came not because he had a muscular chest, but a misshapen one. Nothing about the major's physique reminded anyone of the marines on the recruiting posters. His direct and aggressive manner, however, shone through. Old hands in 1/7 liked to tell the story of the afternoon Major Puller had marched his battalion off to the boondocks. A loudmouth from another outfit had heckled them about the camouflage they wore. As his companies marched past, Puller had spied Private Murphy in Charlie Company. "Old Man," Puller had asked Murphy, "are you going to let him say those things about your company?" Murphy had stepped out of formation, punched the heckler in the kisser, and stepped back into formation. No one missed a step.33 The new men had been around just long enough not to believe everything they heard, but they also knew the story epitomized the Marine Corps spirit being imbued in them.

IN THE PAST FEW WEEKS, SHOFNER HAD FOUND PILES OF SILVER COINS LEFT abandoned. Marines who had swiped them while helping to load the Philippine treasury on barges had realized that money had no value. Three hundred silver dollars, once a princely sum, was now regarded as deadweight. His marines expected their future to resemble the unmerciful pounding that was destroying their comrades on Bataan. The abandoned money, while remarkable, made more sense to Shifty than the radio broadcasts he heard. A radio station in San Francisco regularly broadcast General MacArthur's communiques, which had been issued from the tunnels beneath the Fourth Marines.

In his pronouncements to the American people, MacArthur had described a different war, a war that he was winning. His headquarters had reported that "Lt. General Masaharu Homma, Commander- in-Chief of the Japanese forces in the Philippines, committed hara- kiri." General Homma had been disgraced by his defeats to MacArthur. "An interesting and ironic detail of the story," the communique had continued, "is that the suicide and funeral rites occurred in the suite at the Manila Hotel occupied by General MacArthur prior to the invasion in Manila."34 Three nights after issuing this empty bluster, MacArthur and his key staff had boarded torpedo boats and fled to Australia.

The departure of General Douglas MacArthur had signified defeat, a defeat rapidly approaching in the last week of March. The enemy's heavy artillery began to swing away from Bataan and toward Corregidor, while their heavy bombers resumed their deliveries. U.S. forces on the Rock denied the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) the use of Manila Harbor and therefore resistance had to be eliminated as quickly as possible.

The destruction placed great demands on all of them. A flight of bombers started fires in the houses around Shofner's barracks on March 24. He organized some firefighters. As they fought the flames, a giant explosion rocked the area. A bomb had hit a store of forty thousand 75mm shells. The shells began exploding, sending shrapnel flying. Shofner and his men prevented the blaze from spreading, then pulled a wounded man away from the conflagration. The next night he led a party to save a radio station from the flames. Two nights later, incendiary bombs ignited buildings next to Middleside Barracks and it looked like a whole line of buildings would go up in flames until Captain Shofner led the team to contain it. It seemed to him that some of the enemy's phosphorus shells had delayed-action fuses; they seemed intended to kill any would-be rescuers. The next night he had to put out a fire in his supply of .50-caliber ammunition, an exceedingly dangerous effort. Without that ammo they could not stop an invasion. On the way back to cover, Shofner heard cries for help. A cave had collapsed. He found a few men and a doctor to help him. They rescued two wounded men and pulled out two corpses. His superior officers told him later they were writing letters of commendation for his actions.

Even as the bombing built toward a crescendo on Corregidor, Shofner learned the truth about Bataan. For weeks, Americans and Filipinos from all service branches had been coming over from the embattled peninsula. These men arrived in need of food and clothing as well as weapons. Some of them had no military training. They had been divided up among all the military units on the island anyway. The Fourth Marines, like the other units, were attempting to train them. Some of what these refugees said he already knew, but much of the story emerged bit by bit, over time.

From the outset, the U.S. and Philippine army forces on Bataan had lacked food and medicine, and had quickly run short on ammunition, artillery support and air cover, and everything else. Worse, this disaster should never have happened. Bataan was supposed to have been prepared for exactly this type of defensive stand. For decades the United States had recognized that in the event of a war with Japan, its forces on Luzon would have to retreat to the Bataan Peninsula and await reinforcements. General Douglas MacArthur had decided in the late 1930s, however, to abandon this plan. The Philippine army, which he had created, and the U.S. Army, which he now commanded, would beat the emperor's troops at the beachhead. His decision meant that Bataan had not been prepared with caches of supplies or by military engineers to a significant degree.

MacArthur's performance had not improved following the news of Pearl Harbor. Many hours after the war began, the enemy's airplanes had found the army's fleet of brand-new "Flying Fortresses" on the ground, parked wingtip to wingtip. The few planes not destroyed had had to flee. Once the Imperial Japanese Army entered the game, it had put MacArthur's armies to rout. Americans and Filipinos had fought to the extent of their training, equipment, and experience. Bravery alone could not stop an experienced and fully equipped foe. When MacArthur had at last issued the order to fall back to Bataan, it had been too late. While combat units fell back in good order, tons of supplies and equipment had had to be abandoned. Tens of thousands of American and Filipino soldiers and sailors, along with an assortment of national guardsmen, airmen, marines, nurses, and coastguardsmen, had held off the Japanese army these past few months while eating the monkeys out of the trees. MacArthur had visited Bataan only once.

The more Austin Shofner learned about Douglas MacArthur, the more it produced within him and so many others a deep and abiding anger. Some debated who was responsible for what, but not him. Captain Shofner insisted that the field marshal, hired to protect the Philippines, alone was responsible for this debacle. Many others agreed. They hung a nickname on him: "Dugout Doug."

On April 6, the word went around that Bataan would fall at any moment. Shofner was trying to get some of the new men squared away in a barracks when a shell struck the far end of the building. The concussion split the door he was leaning against, sending him reeling and knocking out a man next to him. Recovering, Shofner went to the blast site. The grisly scene shocked him. Five men had been killed and twenty-five had been wounded. He and others loaded the wounded into a truck and Shofner drove it through the artillery barrage to the hospital. The empire had endless amounts of shells to fire. Later, one wounded army corpsman screamed, "Let me die! Let me die!" as Shofner put him on a stretcher. In the hours that followed, he had more and more close calls. The concussions gave him and his men blackouts. They spent much of their time in their caves and tunnels, where the throbbing and shaking earth tortured them.

On the day Bataan surrendered, April 9, small boats filled with desperate men tried to make it to Corregidor. The marines could see them. The first shots by the enemy's artillery sent great geysers of water into the air. Slowly, though, the Japanese got the range. A few shells got close enough to damage one or two of the boats. The passengers jumped in the water and tried to swim. It was about two and a half miles from shore to shore. Not many of them made it. The Fourth Marines spent that night on alert, expecting an invasion at any moment. They did not expect, however, to receive any help from their countrymen. General Wainwright, who had taken command after MacArthur had departed, had told them the truth: they were being sacrificed.

THE EVENING OF APRIL 10 FOUND MANILA JOHN IN THE ATLANTIC OCEAN, aboard USS Heywood. The scuttlebutt had been right. The Seventh Marines were leading the counterattack. Along with their trucks, machine shops, tanks, water purification units, and antiaircraft guns, the Seventh had been joined by batteries of artillerymen and companies of engineers.35 The 1st Raider Battalion, a new unit in the corps designed to operate behind enemy lines, also had joined them. Standing out on the weather deck, Manila John and his buddy, Sergeant J. P. Morgan, would have seen the dark shapes of the other troopships and of the destroyers guarding them. No lights issued from the flotilla. The question was, where were they going? In the past month speculation had run from Iceland, where the Second Marines were, to Alaska. Although they had not been told, the marines could tell they were sailing south. This course would probably not lead them to Europe. The likelihood of service in the Pacific became a certainty when they reached the Panama Canal. The question then became, where did one start fighting the Japanese? Manila had fallen, as had Guam and Wake; only the men on Corregidor yet held their ground.

THERE HAD BEEN NO FINAL EXAM. TEN DAYS EARLIER MIKE HAD LISTENED TO some of the other pilots talking about boarding a ship. Minutes later the CO had walked up to him and said, "You're on it, go to Pearl." In the early afternoon of April 16, he stood topside and watched his ship enter Pearl Harbor. It looked like the bombs had just exploded. Six inches of oil covered the water. It stank. It stuck to everything. Micheel saw men working in that awful soup, slowly righting the wrecked ships. Other crews looked like they were trying to recover the bodies of sailors. Four months ago right there, he thought, men had drowned inside their ships; others had been trapped without food, water, oxygen. A wave of sadness at the loss of life broke quickly, leaving a new desire. Mike wanted to exact revenge. He was here to get them. He set off down the gangway to find the Administrative Office of the U.S. Pacific Fleet's Commander Carriers at Ford Island, in the middle of Pearl Harbor. He reported for duty, only to be told USS Enterprise had left on a mission and would return in a week or so. His squadron, Scouting Six, had an office at the Naval Air Station (NAS) on the other side of the island, on Kaneohe Bay.

Two days later, Mike took his first flight from NAS Kaneohe Bay to familiarize himself with the area. An experienced pilot from his squadron rode in the rear seat. Mike, the pilot behind him, and the whole island of Oahu were buzzing with the news making headlines that day. The United States had bombed four industrial areas in Japan, including one in Tokyo. The news story had come from the Japanese government, which had condemned "the inhuman attack" on schools and hospitals.36 The Americans cheering "Yippee" and "Hooray" replied to the Japanese government's indictment with a countercharge. " They bombed our hospital on Bataan. Give it to them now!"37 For Micheel, an Iowan not given to cheering, the bombs had put the Japanese on notice. Americans weren't going to give up.

In the days that followed, Mike helped to prepare for the return of his squadron by ferrying in new planes. The newspapers continued with the big news. Tokyo asserted that the bombing strike had been carried out by B- 25s, a two-engine bomber used by the U.S. Army. The B- 25s, they continued, had been launched from three U.S. carriers, flown over Japan, and landed in China. British journalists confirmed the arrival of U.S. planes in China, but the local reporters examined all the possible angles. The Honolulu Star- Bulletin reminded readers the navy had a carrier-based bomber, the Dauntless, and doubted that a plane of the size and weight of the B-25 could be flown onto a carrier.38 Neither the navy nor the War Department offered any comment. The information was classified. When a reporter asked President Roosevelt from whence those American planes had come, he smiled and said, "Shangri La."

The return of USS Enterprise also was classified. Hours before it arrived, Scouting Six flew off its deck and landed at Kaneohe Bay. Micheel's introduction to his new squadron was cool; they were not welcoming and he was not one to break the ice. Thankfully a number of new pilots were joining it, including Ensign John Lough.39 John and Mike had gone through flight training together, starting all the way back in Iowa with preflight. On the weekends, they had shared car rides home together, so they knew each other's families. John had gone to the ACTU in Norfolk, but somehow they had wound up together for the big day. April 29 passed in a whirlwind of preparations, culminating with Scouting Six landing on the deck of the carrier affectionately known as the Big E. Mike and John landed riding in the rear seats, not the cockpits. Tomorrow the Big E would sail into the combat zone. Tomorrow, Mike and John and other new pilots would have to make their first landings on the flight deck, then do it twice more to qualify as carrier pilots.

That challenge would wait until tomorrow. One of Mike's first tasks was to stow his gear in his room. Pilots received some of the best rooms on a carrier, even junior officers like Ensign Micheel, although the staterooms of senior pilots had portals. He shared a room with Bill Pittman. Bill had been on board since December, but he had just been switched from Bombing Six to Scouting Six.40 Pittman showed Mike the way through the great maze that is a fleet carrier. Located on the hangar deck, near the bow, their stateroom was not too hard to find. Standing in the doorway, Bill said, "Well, I guess we have to make a decision here. Who's going to get the upper or lower bunk?"

"I don't know. How are we going to make the decision?"

"What's your service number?" Bill asked. "The guy with the lower serial number will get the lower bunk."

"Mine," said Mike, reciting from memory, "is 99986."

"Mine is 99984."

"Okay," Mike conceded, "you get the lower bunk." He did not care much, so it never occurred to him to ask to see Bill's service number.