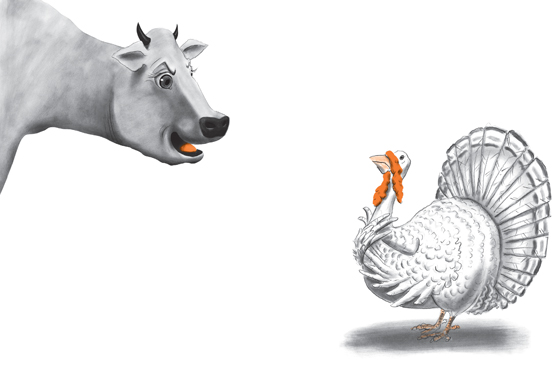

The Cow and the Turkey

The cow was notoriously cheap, so it surprised everyone when she voted yes for the secret Santa scheme. It was the horse’s suggestion, and she backed it immediately, saying, “I choose the turkey.”

The pig, who considered himself an authority on all things gifty, cleared his throat. “That’s not actually the way it works,” he said. “It’s secret, see, so we each draw a name and keep it to ourselves until Christmas morning.”

“Why do you always have to be like that?” the cow asked, and the duck sighed, “Here we go.”

“First you ask me to give someone a Christmas present,” the cow continued, “and then you tell me it has to be done your way. Like, ‘Oh, I have four legs so I’m better than everyone else.’ ”

“Don’t you have four legs?” the pig asked.

The cow loosed something between a moan and a sigh. “All right, just because you have a curly tail,” she said.

The pig tried looking behind him, but all he could see were his sides. “Is it curly curly?” he asked the rooster. “Or curly kinky?”

“The point is that I’m tired of being pushed around,” the cow said. “I think a lot of us are.”

This was her all over, so rather than spending the next week listening to her complain, it was decided that the cow would give to the turkey and that everyone else would keep their names a secret.

There were, of course, no shops in the barnyard, which was a shame, as all of the animals had money, coins mainly, dropped by the farmer and his plump, moody children as they went about their chores. The cow once had close to three dollars and gave it to a calf the family was taking into town. “I want you to buy me a knapsack,” she’d told him. “Just like the one the farmer’s daughter has, only bigger and blue instead of green. Can you remember that?”

The calf had tucked the money into his cheek before being led out of the barn. “And wouldn’t you know it,” the cow later complained, “isn’t it just my luck that he never came back?”

She’d spent the first few days of his absence in a constant, almost giddy state of anticipation. Watching the barn door, listening for the sound of the truck, waiting for that knapsack—something that would belong only to her.

When it no longer made sense to hope, she turned to self-pity, then rage. The calf had taken advantage of her, had spent her precious money on a bus ticket and boarded thinking, So long, sucker.

It was a consolation, then, to overhear the farmer talking to his wife and learn that “taking an animal into town” was a euphemism for hitting him in the head with an electric hammer. So long, sucker.

Milking put the cow in close proximity to humans, much closer than any of the other animals, and she learned a lot by keeping her ears open: who was dating whom, how much it cost to fill a gas tank, any number of useful little tidbits—the menu for Christmas dinner, for instance. The family had spent Thanksgiving visiting the farmer’s mother in her retirement home and had eaten what tasted like potato chips soaked in chicken fat. Now they were going to make up for it “big-time,” the farmer’s wife said, “and with all the trimmings.”

The turkey didn’t know that he would be killed on Christmas Eve; no one knew except the cow. That’s why she’d specifically chosen his name for the secret Santa program—it got her off the hook and made tolerable his constant, fidgety enthusiasm.

“You’ll never in a million years guess what I got you,” she said to him a day after the names were drawn.

“Is it a bath mat?” the turkey asked. He’d seen one hanging on the farmer’s clothesline and was promptly, senselessly, taken by it. “It’s a towel for the floor!” he kept telling everyone. “I mean, really, isn’t that just the greatest idea you’ve ever heard in your life?”

“Oh, this is a lot better than a bath mat,” the cow said, beaming as the turkey sputtered, “No way!” and “What could possibly be better than a bath mat?”

“You’ll see come Christmas morning,” she told him.

Most of the animals were giving food as their secret Santa gift. No one came out and actually said it, but the cow had noticed them setting a little aside, not just scraps but the best parts—the horse her oats, the pig his thick crusts of bread. Even the rooster, who was the biggest glutton of all, had managed to sacrifice and had stockpiled a fistful of grain behind an empty gas can in the far corner of the barn. He and the others were surely hungry, yet none of them complained about it. And this bothered the cow more than anything. Which of you is sacrificing for me? she wondered, her mouth watering at the thought of a treat. She looked at the pig, who sat smiling in his pen, and then at the turkey, who’d hung a sprig of mistletoe from the end of his wattle and was waltzing from one animal to the next, saying, “Any takers?” Even to other guys.

Oh, how his cheerfulness grated on her. Waiting for Christmas Eve was murder, but wait the cow did, and when the time was right—just shortly after breakfast—she sidled up beside him. “You do know they’ll be cutting your head off, don’t you?” she whispered.

The turkey offered his strange half smile, the one that said both “You’re kidding” and “Please tell me you’re kidding.”

“If it’s not the farmer, it’ll be one of his children,” the cow confided. “The middle one, probably, the boy with the earring. There were some jokes about doing it with a chain saw, but if I know them they’ll stick to the ax. It’s more traditional, and we all know how they love a tradition.”

The turkey laughed, deciding it was a joke, but then he saw the pleasure in the cow’s face and knew that she was telling the truth.

“How long have you known?” he asked.

“A few weeks,” the cow told him. “I meant to tell you earlier, but with all the excitement, I guess I forgot.”

“Kill me and eat me?”

The cow nodded.

The turkey pulled the mistletoe from the end of his wattle. “Well, golly,” he said. “Don’t I feel stupid.”

Not wanting to spoil anyone’s Christmas, the turkey announced that he would be spending the holiday with relatives. “The wild side of the family,” he said. “Just flew in last night from Kentucky.” Noon arrived, and when the farmer and his middle son appeared in the barnyard, the turkey went to them without a fuss, saying, “So long everyone” and “See you in a few days.”

They all waved good-bye except for the cow, who lowered her head toward her empty trough. She was just thinking that a little extra food might be nice, when something horrible occurred to her. The rooster was standing in the doorway, and she almost trampled him on her way outside, shouting, “Wait! Come back. Whose name did you draw?”

“Say what?” the turkey said.

“I said, whose name did you get? Who’s supposed to receive your secret Santa present?”

The turkey answered a thin, “You’ll see,” his voice a little song that hung in the air long after he’d disappeared.